Capture of Saint Vincent

| Capture of Saint Vincent | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

D'Estaing Trolong du Rumain Chatoyer |

Valentine Morris George Etherington | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 frigate 2 corvettes 2 sloops 300–500 regulars and militia 800 local Black Caribs | 464 Royal American Regiment infantry (252 listed as fit for duty) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

None reported 82 men lost by shipwreck[1] |

2 merchant ships captured 422 men captured | ||||||

The Capture of Saint Vincent was a French invasion that took place between 16 and 18 June 1779 during the American Revolutionary War. A French force commander named Charles-Marie de Trolong du Rumain landed on the island of Saint Vincent in the West Indies and quickly took over much of the British-controlled part of the island, assisted by local Black Caribs who held the northern part of the island.

British Governor Valentine Morris and military commander Lieutenant Colonel George Etherington disagreed on how to react and ended up surrendering without significant resistance. Both leaders were subjected to inquiries over the surrender. The period of French control began by capturing the island, which resulted in a solidified Black Carib control over northern parts of the island. The area remained under Carib control until the Second Carib War of 1795.

Background

[edit]Following the entry of France into the American War of Independence as an American ally in early 1778, French Admiral the Comte d'Estaing arrived in the West Indies in early December 1778 in command of a fleet consisting of 12 ships of the line and a number of smaller vessels.[2] At about the same time a British fleet under Admiral William Hotham also arrived, augmenting the fleet of Admiral Samuel Barrington.[3] The British then captured French-held St. Lucia, despite d'Estaing's attempt at relief. The British used St. Lucia to monitor the major French base at Martinique, where d'Estaing was headquartered.[4]

The British fleet was further reinforced in January 1779 by ten ships of the line under Admiral John Byron, who assumed command of the British Leeward Islands station.[5] Throughout the first half of 1779 both fleets received further reinforcements, after which the French fleet was slightly superior to that of the British.[6] Furthermore, Byron departed St. Lucia on 6 June in order to provide escort services to British merchant ships gathering at St. Kitts for a convoy to Europe, leaving d'Estaing free to act. D'Estaing and the governor, François Claude Amour, marquis de Bouillé, seized the opportunity to begin a series of operations against nearby British possessions. Their first target was the isle of Saint Vincent, just south of St. Lucia.[7]

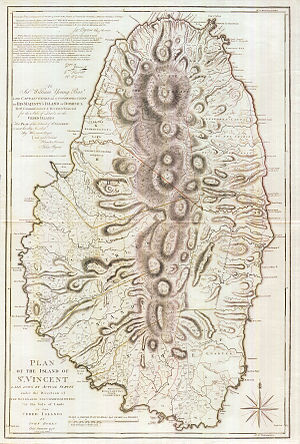

The political situation on Saint Vincent was somewhat tense. The island was divided roughly in half between land controlled by white planters (principally British) and that controlled by the local Black Carib population. The line dividing these territories ran from the island's north-west to its south-east, and had been agreed in a treaty signed in 1773 after the First Carib War. Neither side had been happy with the compromise agreement, and its terms were a continuing source of friction.[8] The British had, uniquely among its Caribbean possessions, had to establish a chain of outposts to protect the planter population.[9]

Saint Vincent's colonial government and defences were in some disarray. Governor Valentine Morris had assumed office in 1776 when the isle was granted a separate government, and reported then that it had virtually no defences. In addition to the difficult relations with the Caribs, the British population was also sympathetic to the cause of colonial independence.[10] The French capture of Dominica in 1778 had raised constitutional questions surrounding the imposition of martial law, and the colonial assembly had consequently refused to appropriate funds for improving the island defences. Governor Morris had spent his own funds instead on improvements, contributing to financial difficulties he would run into later.[11]

The only British military presence on the island was a garrison of about 450 men from the Royal American Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Etherington, most of whom were poorly trained recruits and about half of whom were unfit for duty. Etherington, rather than training and drilling his troops, or fully staffing the island's outposts, was employing significant numbers of them to clear land on an estate on the north-west side of the island.[10] Etherington's estate was on territory on the Carib side of the island, and its grant (for Etherington's service in the Seven Years' War, but made under circumstances the Caribs viewed as illegal) was a major source of annoyance to the Caribs.[12] Governor de Bouillé had established regular contact with the Caribs, and was supplying them with arms.[13] In late August 1778 French officials met with Carib leader Joseph Chatoyer, and in early September Governor Morris was confronted by Caribs bearing new French muskets on a tour of the border areas.[14]

Composition

[edit]French Forces

[edit]French forces included:[15]

- Baritaut's Company from Régiment de Champagne

- Captain Germiny's Company from Régiment de Viennois

- Régiment de la Martinique (2 Battalions)

British Forces

[edit]British forces included:[16]

- 400 Men of unknown battalion from 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot

Capture

[edit]

D'Estaing organized a force of 300 to 500 troops, including French regulars drawn from the regiments Champagne, Viennois, and Martinique, and about 200 volunteer militia from Martinique.[17][18] The invasion force was placed under the command of Lieutenant de vaisseau Charles Marie de Trolong du Rumain, who had recently distinguished himself by taking over British-controlled Saint Martin in March 1779. The force was embarked on a fleet consisting of the frigate Lively, the corvettes Lys and Balleastre, and two privateers.[1][19] Du Rumain sailed from Martinique on 9 June, and reached the waters off Saint Vincent on the 16th. One of the privateers was driven ashore on the windward side of the island, losing 82 men.[1]

Two of the ships anchored in Young's Bay, near Calliaqua, while the third anchored off Kingstown. The ships flew no national colours, leading to local speculation as to their intent. Local planters who thought they might be merchant vessels expected to pick up the sugar harvest prevented a sentry at one of the island's coastal fortifications from firing a signal cannon, and one man sent out to one of the ships was taken prisoner. As the French began landing their troops, a small company under Captain Percin de la Roque was landed on the eastern shore to mobilise the Caribs.[1][20][21] These irregular forces, which grew to number about 800, quickly overran British settlements near the borders between the British lands and those of the Caribs, while du Rumain led his main body of troops toward Kingstown.[22]

The alarm was eventually raised, and Governor Morris thought it would be possible to make a stand against the French in the hills above Kingstown, in hopes that the Royal Navy would bring relief. Lieutenant Colonel Etherington was however opposed to this, especially when the size of the approaching Carib force became apparent, and a truce flag was sent to the French.[23] Du Rumain demanded an unconditional surrender, which Morris rejected. During the negotiations, three ships were spotted flying British flags. Du Rumain returned to his ship, and quickly determined that the strangers were supply ships; two he captured, but the third got away.[1][23] After further negotiations terms were agreed that were similar to those granted by de Bouillé in the 1778 capture of Dominica.[23]

Aftermath

[edit]After du Rumain's success, d'Estaing sailed with his entire fleet for Barbados at the end of June, but was unable to make significant progress against the prevailing winds.[24] He gave up the attempt, sailing instead for Grenada, which he captured on 5 July. Admiral Byron had been alerted to the capture of Saint Vincent on 1 July, and was preparing a force to retake it when he learnt of the attack on Grenada. He immediately sailed there, arriving on the morning of 6 June. The fleets battled off Grenada, with d'Estaing prevailing over Byron's disorganized attack.[25] Both Grenada and Saint Vincent remained in French hands until the end of the war, when they were returned to Britain under the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris.[26]

Admiral George Brydges Rodney made an attempt to recover Saint Vincent in December 1780. Arriving in the Caribbean after one of the worst hurricane seasons on record, Rodney acted on rumours that Saint Vincent's defences had been devastated by an October hurricane that wrought havoc throughout the West Indies,[27][28] and sailed to Saint Vincent with ten ships of the line and 250 soldiers under General John Vaughan. Although Saint Vincent had suffered significant damage (most of the buildings in Kingstown were destroyed), the defences above Kingstown were in good condition and defended by 1,000 French and Carib soldiers.[29][30] Vaughan's troops were landed, but they found the going difficult due to the conditions, and were re-embarked after only one day.[31]

Lieutenant Colonel Etherington was subjected to an enquiry at St. Lucia in 1781 over his conduct during the invasion, and exonerated.[32] Governor Morris, a long-time resident of the island, demanded an inquiry into his behaviour, alleging it had been misrepresented in the press and other writings; he was also vindicated.[33] He never returned to the island, dying in England in 1789 after spending seven years in King's Bench Prison over debts incurred, in part, due to spending on Saint Vincent's defences.[34]

The Black Caribs actively harassed British settlers during the French occupation, at times requiring intervention of the French military to minimize bloodshed. After the return to British control, an uneasy peace existed between the British and Caribs until the 1790s, when the Caribs again rose up in the Second Carib War (part of radical French efforts to export the French Revolution).[35] The Caribs were then deported by the British to Roatán, an island off the coast of present-day Honduras, where their descendants are now known as the Garifuna people.[36] Saint Vincent and the Grenadines gained its independence from Britain in 1979.[37]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Levot, p. 795

- ^ Mahan, pp. 429–431

- ^ Mahan, p. 429

- ^ Mahan, pp. 429–432

- ^ Colomb, p. 388

- ^ Colomb, pp. 388–389

- ^ Colomb, p. 389

- ^ Craton, pp. 151–153

- ^ Morris, p. xv

- ^ a b Shephard, pp. 36–38

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, pp. 187, 193

- ^ Craton, pp. 148, 190

- ^ Shephard, pp. 38–39

- ^ Taylor, pp. 87–88

- ^ Louis Susane, Infantry of the Ancient French Infantry (Multiple Volumes).

- ^ "British War with France and Spain, 1778-1783". 13 October 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ Chartrand, p. 3

- ^ Shephard, p. 41

- ^ Guérin, p. 71

- ^ Shephard, pp. 40, 163

- ^ Taylor, p. 88

- ^ Levot, p. 796

- ^ a b c Shepard, pp. 42–43

- ^ Colomb, p. 390

- ^ Colomb, p. 391

- ^ Black, p. 59

- ^ Shephard, p. 47

- ^ Ludlum, p. 66

- ^ Guérin, p. 89

- ^ Taylor, p. 95

- ^ Shephard, p. 48

- ^ See Harburn et al for details

- ^ Morris, pp. 305–306

- ^ Bourn, p. 599

- ^ Craton, p. 190

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 226

- ^ Treaties in Force 2010, p. 237

References

[edit]- Black, Jeremy (2006). A Military History of Britain: From 1775 to the Present. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-99039-8. OCLC 70483433.

- Bourn, Thomas (1815). A Gazetter of the Most Remarkable Places in the World. London: Mawman. OCLC 166063695.

- Chartrand, Rene (1992). The French Army in the American War of Independence. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-167-0. OCLC 635271744.

- Colomb, Philip (1895). Naval Warfare, its Ruling Principles and Practice Historically Treated. London: W. H. Allen. p. 386. OCLC 2863262.

- Craton, Michael (2009) [1982]. Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1252-3. OCLC 8765752.

- Guérin, Léon (1851). Histoire Maritime de France, Volume 5 (in French). Paris: Dufour et Mulat. p. 89. OCLC 16966590.

- Harburn, Todd; Durham, Rodger (2002). "A Vindication of my Conduct" : the General Court Martial of Lieutenant Colonel George Etherington of the 60th or Royal American Regiment Held on the Island of St. Lucia in October 1781 and the Extraordinary Story Regarding the Surrender of the Island of St. Vincent in the British Caribbean during the American Revolution. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-2092-4. OCLC 182527605.

- Levot, Prosper Jean (1857). Biographie bretonne, Volume 2 (in French). Vannes: Cauderan. OCLC 67890505.

- Ludlum, David M. (1963). Early American Hurricanes, 1492–1870. Boston: American Meteorological Society. OCLC 511649.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1898). Major Operations of the Royal Navy, 1762–1783: Being Chapter XXXI in The Royal Navy. A History. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 46778589.

- Morris, Valentine (1787). Narrative of the Official Conduct of Valentine Morris. London: J. Walter. OCLC 5366175. Self-publication by Morris of documents pertaining to his tenure as governor, including affidavits gathered for inquiries after the capture, and the articles of capitulation.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson (2000). An Empire Divided: the American Revolution and the British Caribbean. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3558-6. OCLC 185896684.

- Rodriguez, Junius (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 1. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2. OCLC 255787790.

- Shephard, Charles (1831). An Historical Account of the Island of Saint Vincent. London: W. Nicol. OCLC 1119052.

- Taylor, Christopher (2012). The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival, and the Making of the Garifuna People. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781617033100. OCLC 759909828.

- U. S. State Department (eds) (2010). Treaties in Force 2010. United States Government. ISBN 978-0-16-085737-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)