Peach

| Peach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Peach flower, fruit, seed and leaves as illustrated by Otto Wilhelm Thomé (1885) | |

| |

| Autumn Red peaches, cross section showing freestone variety | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Prunus |

| Subgenus: | Prunus subg. Amygdalus |

| Species: | P. persica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Prunus persica | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

The peach (Prunus persica) is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China.[3] It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, non-fuzzy varieties), nectarines.

The specific name persica refers to its widespread cultivation in Persia (modern-day Iran), from where it was transplanted to Europe and in the 16th century to the Americas. It belongs to the genus Prunus, which includes the cherry, apricot, almond, and plum, and which is part of the rose family. The peach is classified with the almond in the subgenus Amygdalus, distinguished from the other subgenera by the corrugated seed shell (endocarp).[4] Due to their close relatedness, the kernel of a peach stone tastes remarkably similar to almond, and peach stones are often used to make a cheap version of marzipan, known as persipan.[5]

Peaches and nectarines are the same species, though they are regarded commercially as different fruits. The skin of nectarines lacks the fuzz (fruit-skin trichomes) that peach skin has; a mutation in a single gene (MYB25) is thought to be responsible for the difference between the two.[6][7]

In 2018, China produced 62% of the world total of peaches and nectarines. Spain, Italy, Turkey and Greece, all situated in the Mediterranean region, are prominent producers of peaches.[8]

Description

Prunus persica trees grow up to 7 m (23 ft) tall and wide, but when pruned properly, they are usually 3–4 m (10–13 ft) tall and wide.[9] The leaves are lanceolate, 7–16 cm (3–6+1⁄2 in) long, 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄4 in) broad, and pinnately veined. The flowers are produced in early spring before the leaves; they are solitary or paired, 2.5–3 cm diameter, pink, with five petals. The fruit has yellow or whitish flesh, a delicate aroma, and a skin that is either velvety (peaches) or smooth (nectarines) in different cultivars. The flesh is very delicate and easily bruised in some cultivars, but is fairly firm in some commercial varieties, especially when green. The single, large seed is red-brown, oval shaped, around 1.3–2 cm long, and surrounded by a wood-like husk. Peaches, along with cherries, plums, and apricots, are stone fruits (drupes). The various heirloom varieties including the 'Indian Peach', or 'Indian Blood Peach', which ripens in the latter part of the summer, and can have color ranging from red and white, to purple.[10]

Cultivated peaches are divided into clingstones and freestones, depending on whether the flesh sticks to the stone or not; both can have either white or yellow flesh. Peaches with white flesh typically are very sweet with little acidity, while yellow-fleshed peaches typically have an acidic tang coupled with sweetness, though this also varies greatly. Both colors often have some red on their skins. Low-acid, white-fleshed peaches are the most popular kinds in China, Japan, and neighbouring Asian countries, while Europeans and North Americans have historically favoured the acidic, yellow-fleshed cultivars.

Peach trees are relatively short-lived as compared with some other fruit trees. In some regions orchards are replanted after 8 to 10 years, while in others trees may produce satisfactorily for 20 to 25 years or more, depending upon their resistance to diseases, pests, and winter damage.[11]

Etymology

The scientific name persica, along with the word peach itself – and its cognates in many European languages – derives from an early European belief that peaches were native to Persia (modern-day Iran). The Ancient Romans referred to the peach as malum persicum ("Persian apple"), later becoming French pêche, whence the English peach.[12] The scientific name, Prunus persica, literally means "Persian plum", as it is closely related to the plum.

Fossil record

Fossil endocarps with characteristics indistinguishable from those of modern peaches have been recovered from late Pliocene deposits in Kunming, dating to 2.6 million years ago. In the absence of evidence that the plants were in other ways identical to the modern peach, the name Prunus kunmingensis has been assigned to these fossils.[13]

History

Although its botanical name Prunus persica refers to Persia, genetic studies suggest peaches originated in China,[14] where they have been cultivated since the Neolithic period. Until recently, cultivation was believed to have started around 2000 BC.[15][16] More recent evidence indicates that domestication occurred as early as 6000 BC in Zhejiang Province of China. The oldest archaeological peach stones are from the Kuahuqiao site near Hangzhou. Archaeologists point to the Yangtze River Valley as the place where the early selection for favorable peach varieties probably took place.[3] Peaches were mentioned in Chinese writings and literature beginning from the early first millennium BC.[17]

A domesticated peach appeared very early in Japan, in 4700–4400 BC, during the Jōmon period. It was already similar to modern cultivated forms, where the peach stones are significantly larger and more compressed than earlier stones. This domesticated type of peach was brought into Japan from China. Nevertheless, in China itself, this variety is currently attested only at a later date around 3300 to 2300 BC.[18]

In India, the peach first appeared by about 1700 BC, during the Harappan period.[19]

It is also found elsewhere in West Asia in ancient times.[20] Peach cultivation reached Greece by 300 BC.[16] Alexander the Great is sometimes said to have introduced them into Greece after conquering Persia,[20] but no historical evidence for this claim has been found.[21] Peaches were, however, well known to the Romans in the first century AD;[16] the oldest known artistic representations of the fruit are in two fragments of wall paintings, dated to the first century AD, in Herculaneum, preserved due to the Vesuvius eruption of 79 AD, and now held in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.[22] Archaeological finds show that peaches were cultivated widely in Roman northwestern Continental Europe, but production collapsed around the sixth century; some revival of production followed with the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century.[23]

An article on peach tree cultivation in Spain is brought down in Ibn al-'Awwam's 12th-century agricultural work, Book on Agriculture.[24] The peach was brought to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 16th century, and eventually made it to England and France in the 17th century, where it was a prized and expensive treat. Horticulturist George Minifie supposedly brought the first peaches from England to its North American colonies in the early 17th century, planting them at his estate of Buckland in Virginia.[25] Although Thomas Jefferson had peach trees at Monticello, American farmers did not begin commercial production until the 19th century in Maryland, Delaware, Georgia, South Carolina, and finally Virginia.[26]

The Shanghai honey nectar peach was a key component of both the food culture and agrarian economy the area where the modern megacity of Shanghai stands. Peaches were the cornerstone of early Shanghai's garden culture. As modernization and westernization swept through the city the Shanghai honey nectar peach nearly disappeared completely. Much of modern Shanghai is built over these gardens and peach orchards.[27]

In April 2010, an international consortium, the International Peach Genome Initiative, which includes researchers from the United States, Italy, Chile, Spain, and France, announced they had sequenced the peach tree genome (doubled haploid Lovell). Recently, it published the peach genome sequence and related analyses. The sequence is composed of 227 million nucleotides arranged in eight pseudomolecules representing the eight peach chromosomes (2n = 16). In addition, 27,852 protein-coding genes and 28,689 protein-coding transcripts were predicted.

Particular emphasis in this study is reserved for the analysis of the genetic diversity in peach germplasm and how it was shaped by human activities such as domestication and breeding. Major historical bottlenecks were found, one related to the putative original domestication that is supposed to have taken place in China about 4,000–5,000 years ago, the second is related to the western germplasm and is due to the early dissemination of the peach in Europe from China and the more recent breeding activities in the United States and Europe. These bottlenecks highlighted the substantial reduction of genetic diversity associated with domestication and breeding activities.[28]

Peaches in the Americas

Peaches were introduced into the Americas in the 16th century by the Spanish. By 1580, peaches were being grown in Latin America and were cultivated by the remnants of the Inca Empire in Argentina.[29]

In the United States the peach was soon adopted as a crop by American Indians. The peach also became naturalized and abundant as a wild species in the eastern U.S.. Peaches were being grown in Virginia as early as 1629. Peaches grown by Indians in Virginia were said to have been "of greater variety and finer sorts" than those of the English colonists. Also in 1629, peaches were listed as a crop in New Mexico. William Penn noted the existence of wild peaches in Pennsylvania in 1683.[30][31] In fact, peaches may have already spread to the American Southeast by the early to mid 16th century, actively cultivated by Indigenous communities before permanent Spanish settlement of the region.[32]

Peach plantations became an objective of American military campaigns against the Indians. In 1779, the Sullivan Expedition destroyed the livelihood of many of the Iroquois people of New York. Among the crops destroyed were plantations of peach trees.[33] In 1864, Kit Carson led a successful U.S. army expedition to Canyon de Chelly, Arizona to destroy the livelihood of the Navajo. Carson destroyed thousands of peach trees. A soldier said they were the "best peach trees I have ever seen in the country, every one of them bearing fruit."[34]

Cultivation

Peaches grow in a fairly limited range in dry, continental or temperate climates, since the trees have a chilling requirement that tropical or subtropical areas generally do not satisfy except at high altitudes (for example in certain areas of Ecuador, Colombia, Ethiopia, India, and Nepal). Most cultivars require 500 hours of chilling around 0 to 10 °C (32 to 50 °F). During the chilling period, key chemical reactions occur, but the plant appears dormant. Once the chilling period is fulfilled, the plant enters a second type of dormancy, the quiescence period. During quiescence, buds break and grow when sufficient warm weather favorable to growth is accumulated.[35]

The trees themselves can usually tolerate temperatures to around −26 to −30 °C (−15 to −22 °F), although the following season's flower buds are usually killed at these temperatures, preventing a crop that summer. Flower bud death begins to occur between −15 and −25 °C (5 and −13 °F), depending on the cultivar and on the timing of the cold, with the buds becoming less cold tolerant in late winter.[36]

Another climate constraint is spring frost. The trees flower fairly early (in March in Western Europe), and the blossom is damaged or killed if temperatures drop below about −4 °C (25 °F). If the flowers are not fully open, though, they can tolerate a few degrees colder.[37]

Climates with significant winter rainfall at temperatures below 16 °C (61 °F) are also unsuitable for peach cultivation, as the rain promotes peach leaf curl, which is the most serious fungal disease for peaches. In practice, fungicides are extensively used for peach cultivation in such climates, with more than 1% of European peaches exceeding legal pesticide limits in 2013.[38]

Finally, summer heat is required to mature the crop, with mean temperatures of the hottest month between 20 and 30 °C (68 and 86 °F).

Typical peach cultivars begin bearing fruit in their third year. Their lifespan in the U.S. varies by region; the University of California at Davis gives a lifespan of about 15 years[39] while the University of Maine gives a lifespan of 7 years there.[40]

Cultivars

Hundreds of peach and nectarine cultivars are known. These are classified into two categories—freestones and clingstones. Freestones are those whose flesh separates readily from the pit. Clingstones are those whose flesh clings tightly to the pit. Some cultivars are partially freestone and clingstone, so are called semifree. Freestone types are preferred for eating fresh, while clingstone types are for canning. The fruit flesh may be creamy white to deep yellow, to dark red; the hue and shade of the color depend on the cultivar.[41]

Peach breeding has favored cultivars with more firmness, more red color, and shorter fuzz on the fruit surface. These characteristics ease shipping and supermarket sales by improving eye appeal. This selection process has not necessarily led to increased flavor, though. Peaches have a short shelf life, so commercial growers typically plant a mix of different cultivars to have fruit to ship all season long.[42]

Different countries have different cultivars. In the United Kingdom, for example, these cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

For China specifically see Peach production in China § Cultivars.

Nectarines

The variety P. persica var. nucipersica (or var. nectarina) – commonly called nectarines – has a smooth skin. It is on occasion referred to as a "shaved peach" or "fuzzless peach", due to its lack of fuzz or short hairs. Though fuzzy peaches and nectarines are regarded commercially as different fruits, with nectarines often erroneously believed to be a crossbreed between peaches and plums, or a "peach with a plum skin", nectarines belong to the same species as peaches. Several genetic studies have concluded nectarines are produced due to a recessive allele, whereas a fuzzy peach skin is dominant.[6] Nectarines have arisen many times from peach trees, often as bud sports.

As with peaches, nectarines can be white or yellow, and clingstone or freestone. On average, nectarines are slightly smaller and sweeter than peaches, but with much overlap.[6] The lack of skin fuzz can make nectarine skins appear more reddish than those of peaches, contributing to the fruit's plum-like appearance. The lack of down on nectarines' skin also means their skin is more easily bruised than peaches.

The history of the nectarine is unclear; the first recorded mention in English is from 1616,[47] but they had probably been grown much earlier within the native range of the peach in central and eastern Asia. Although one source states that nectarines were introduced into the United States by David Fairchild of the Department of Agriculture in 1906,[48] a number of colonial-era newspaper articles make reference to nectarines being grown in the United States prior to the Revolutionary War. The 28 March 1768 edition of the New York Gazette (p. 3), for example, mentions a farm in Jamaica, Long Island, New York, where nectarines were grown.

Peacherines

Peacherines are claimed to be a cross between a peach and a nectarine, but as they are the same species cannot be a true cross (hybrid); they are marketed in Australia and New Zealand. The fruit is intermediate in appearance, though, between a peach and a nectarine, large and brightly colored like a red peach. The flesh of the fruit is usually yellow, but white varieties also exist. The Koanga Institute lists varieties that ripen in the Southern Hemisphere in February and March.[49][50]

In 1909, Pacific Monthly mentioned peacherines in a news bulletin for California. Louise Pound, in 1920, claimed the term peacherine is an example of language stunt.[51]

Flat peaches

Flat peaches, or pan-tao, have a flattened shape, in contrast to ordinary near-spherical peaches.[52]

Planting

Most peach trees sold by nurseries are cultivars budded or grafted onto a suitable rootstock. Common rootstocks are 'Lovell Peach', 'Nemaguard Peach', Prunus besseyi, and 'Citation'.[53] The rootstock provides hardiness and budding is done to improve predictability of the fruit quality.

Peach trees need full sun, and a layout that allows good natural air flow to assist the thermal environment for the tree. Peaches are planted in early winter. During the growth season, they need a regular and reliable supply of water, with higher amounts just before harvest.[54]

Peaches need nitrogen-rich fertilizers more than other fruit trees. Without regular fertilizer supply, peach tree leaves start turning yellow or exhibit stunted growth. Blood meal, bone meal, and calcium ammonium nitrate are suitable fertilizers.

The flowers on a peach tree are typically thinned out because if the full number of peaches mature on a branch, they are undersized and lack flavor. Fruits are thinned midway in the season by commercial growers. Fresh peaches are easily bruised, so do not store well. They are most flavorful when they ripen on the tree and are eaten the day of harvest.[54]

The peach tree can be grown in an espalier shape. The Baldassari palmette is a design created around 1950 used primarily for training peaches. In walled gardens constructed from stone or brick, which absorb and retain solar heat and then slowly release it, raising the temperature against the wall, peaches can be grown as espaliers against south-facing walls as far north as southeast Great Britain and southern Ireland.

Insects

The first pest to attack the tree early in the year when other food is scarce is the earwig (Forficula auricularia) which feeds on blossoms and young leaves at night, preventing fruiting and weakening newly planted trees. The pattern of damage is distinct from that of caterpillars later in the year, as earwigs characteristically remove semicircles of petal and leaf tissue from the tips, rather than internally. Greasebands applied just before blossom are effective.[55][failed verification]

The larvae of such moth species as the peachtree borer (Synanthedon exitiosa), the yellow peach moth (Conogethes punctiferalis), the well-marked cutworm (Abagrotis orbis), Lyonetia prunifoliella, Phyllonorycter hostis, the fruit tree borer (Maroga melanostigma), Parornix anguliferella, Parornix finitimella, Caloptilia zachrysa, Phyllonorycter crataegella, Trifurcula sinica, Suzuki's promolactis moth (Promalactis suzukiella), the white-spotted tussock moth (Orgyia thyellina), the apple leafroller (Archips termias), the catapult moth (Serrodes partita), the wood groundling (Parachronistis albiceps) or the omnivorous leafroller (Platynota stultana) are reported to feed on P. persica. The flatid planthopper (Metcalfa pruinosa) causes damage to fruit trees.

The tree is also a host plant for such species as the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), the unmonsuzume (Callambulyx tatarinovii), the promethea silkmoth (Callosamia promethea), the orange oakleaf (Kallima inachus), Langia zenzeroides, the speckled emperor (Gynanisa maja) or the brown playboy (Deudorix antalus). The European red mite (Panonychus ulmi) or the yellow mite (Lorryia formosa) are also found on the peach tree.

It is a good pollen source for honey bees and a honeydew source for aphids.

Diseases

Peach trees are prone to a disease called leaf curl, which usually does not directly affect the fruit, but does reduce the crop yield by partially defoliating the tree. Several fungicides can be used to combat the disease, including Bordeaux mixture and other copper-based products (the University of California considers these organic treatments), ziram, chlorothalonil, and dodine.[56] The fruit is susceptible to brown rot or a dark reddish spot.

Storage

Peaches and nectarines are best stored at temperatures of 0 °C (32 °F) and in high humidity.[41] They are highly perishable, so are typically consumed or canned within two weeks of harvest.

Peaches are climacteric[57][58][59] fruits and continue to ripen after being picked from the tree.[60]

Production

| Peach (and nectarine) production, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions of tonnes) | |

| 15.00 | ||

| 1.31 | ||

| 1.02 | ||

| 0.89 | ||

| 0.89 | ||

| 0.66 | ||

| 0.56 | ||

| World | 24.57 | |

| Source: United Nations, FAOSTAT[8] | ||

In 2020, world production of peaches (combined with nectarines for reporting) was 24.6 million tonnes, led by China with 61% of the world total (table).

The U.S. state of Georgia is known as the "Peach State" due to its significant production of peaches as early as 1571,[61] with exports to other states occurring around 1858.[62] In 2014, Georgia was third in US peach production behind California and South Carolina.[61] The largest peach producing countries in Latin America are Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.[63]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 165 kJ (39 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

9.54 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 8.39 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 1.5 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.25 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.91 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 89 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[64] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[65] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Raw peach flesh is 89% water, 10% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat. A medium-sized raw peach, weighing 100 g (3.5 oz), supplies 39 calories, and contains small amounts of essential nutrients, but none is a significant proportion of the Daily Value (DV, right table). A raw nectarine has similar low content of nutrients.[66] The glycemic load of an average peach (120 grams) is 5, similar to other low-sugar fruits.[67]

One medium peach also contains 2% or more daily value of vitamins E and K, niacin, folate, iron, choline, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, zinc and copper. Fresh peaches are a moderate source of antioxidants and vitamin C which is required for the building of connective tissue inside the human body.[68]

Phytochemicals

Total polyphenols in mg per 100 g of fresh weight were 14–102 in white-flesh nectarines, 18–54 in yellow-flesh nectarines, 28–111 in white-flesh peaches, and 21–61 mg per 100 g in yellow-flesh peaches.[69] The major phenolic compounds identified in peach are chlorogenic acid, catechins and epicatechins,[70] with other compounds, identified by HPLC, including gallic acid and ellagic acid.[71] Rutin and isoquercetin are the primary flavonols found in clingstone peaches.[72]

Red-fleshed peaches are rich in anthocyanins,[73] particularly cyanidin glucosides in six peach and six nectarine cultivars[74] and malvin glycosides in clingstone peaches.[72] As with many other members of the rose family, peach seeds contain cyanogenic glycosides, including amygdalin (note the subgenus designation: Amygdalus).[75] These substances are capable of decomposing into a sugar molecule and hydrogen cyanide gas.[76][75] Cyanogenic glycosides are toxic if consumed in large doses.[77] While peach seeds are not the most toxic within the rose family (see bitter almond), large consumption of these chemicals from any source is potentially hazardous to animal and human health.[76]

Peach allergy or intolerance is a relatively common form of hypersensitivity to proteins contained in peaches and related fruits (such as almonds). Symptoms range from local effects (e.g. oral allergy syndrome, contact urticaria) to more severe systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis (e.g. urticaria, angioedema, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms).[78] Adverse reactions are related to the "freshness" of the fruit: peeled or canned fruit may be tolerated.

Aroma

Some 110 chemical compounds contribute to peach aroma, including alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, esters, polyphenols and terpenoids.[79]

Cultural significance

Peaches are not only a popular fruit, but also are symbolic in many cultural traditions, such as in art, paintings, and folk tales such as the Peaches of Immortality.

China

Peach blossoms are highly prized in Chinese culture. The ancient Chinese believed the peach to possess more vitality than any other tree because their blossoms appear before leaves sprout. When early rulers of China visited their territories, they were preceded by sorcerers armed with peach rods to protect them from spectral evils. On New Year's Eve, local magistrates would cut peach wood branches and place them over their doors to protect against evil influences.[80] Peach wood was also used for the earliest known door gods during the Han. Another author writes:

The Chinese also considered peach wood (t'ao-fu)(Chinese: 桃符; pinyin: Táofú) protective against evil spirits, who held the peach in awe. In ancient China, peach-wood bows were used to shoot arrows in every direction in an effort to dispel evil. Peach-wood slips or carved pits served as amulets to protect a person's life, safety, and health.[81]

Peachwood seals or figurines guarded gates and doors, and, as one Han account recites, "the buildings in the capital are made tranquil and pure; everywhere a good state of affairs prevails".[81] Writes the author, further:

Another aid in fighting evil spirits were peach-wood wands. The Li-chi (Han period) reported that the emperor went to the funeral of a minister escorted by a sorcerer carrying a peachwood wand to keep bad influences away. Since that time, peachwood wands have remained an important means of exorcism in China.[81]

Peach kernels Tao ren (Chinese: 桃仁; pinyin: Táorén) are a common ingredient used in traditional Chinese medicine to dispel blood stasis, counter inflammation, and reduce allergies.[82]

In an orchard of flowering peach trees, Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei took an oath of brotherhood in the opening chapter of the classic Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Another peach orchard, in "The Peach Blossom Spring" by poet Tao Yuanming, is the setting of the favourite Chinese fable and a metaphor for utopias. A peach tree growing on a precipice was where the Taoist master Zhang Daoling tested his disciples.[83]

The Old Man of the South Pole, one of the deities of the Chinese folk religion Fu Lu Shou (Chinese: 福祿壽; pinyin: Fú lù shòu), is sometimes seen holding a large peach, representing long life and health.[citation needed]

The term "bitten peach", first used by Legalist philosopher Han Fei in his work Han Feizi, became a byword for homosexuality. The book records the incident when courtier Mizi Xia bit into an especially delicious peach and gave the remainder to his lover, Duke Ling of Wei, as a gift so that he could taste it, as well.[citation needed]

Korea

In Korea, peaches have been cultivated from ancient times. According to Samguk Sagi, peach trees were planted during the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, and Sallim gyeongje also mentions cultivation skills of peach trees. The peach is seen as the fruit of happiness, riches, honours, and longevity. The rare peach with double seeds is seen as a favorable omen of a mild winter. It is one of the 10 immortal plants and animals, so peaches appear in many minhwa (folk paintings). Peaches and peach trees are believed to chase away spirits, so peaches are not placed on tables for jesa (ancestor veneration), unlike other fruits.[84][85]

Japan

The world's sweetest peach is grown in Fukushima, Japan. The Guinness world record for the sweetest peach is currently held by a peach grown in Kanechika, Japan, with a sugar content of 22.2%. However, a fruit farm in rural Fukushima, Koji grew a much sweeter peach, with a Brix score of 32°. Degrees Brix measures the sugar content of the fruit, and is usually between 11 and 15 for a typical peach from a supermarket.[86]

Momotarō, a folktale character, is named after the giant peach from which he was birthed.

Two traditional Japanese words for the color pink correspond to blossoming trees: one for peach blossoms (momo-iro), and one for cherry blossoms (sakura-iro).

Vietnam

A Vietnamese mythic history states that in the spring of 1789, after marching to Ngọc Hồi and then winning a great victory against invaders from the Qing dynasty of China, Emperor Quang Trung ordered a messenger to gallop to Phú Xuân citadel (now Huế) and deliver a flowering peach branch to the Empress Ngọc Hân. This took place on the fifth day of the first lunar month, two days before the predicted end of the battle. The branch of peach flowers that was sent from the north to the centre of Vietnam was not only a message of victory from the Emperor to his consort, but also the start of a new spring of peace and happiness for all the Vietnamese people. In addition, since the land of Nhật Tân had freely given that very branch of peach flowers to the Emperor, it became the loyal garden of his dynasty.

The protagonists of The Tale of Kieu fell in love by a peach tree, and in Vietnam, the blossoming peach flower is the signal of spring. Finally, peach bonsai trees are used as decoration during Vietnamese New Year (Tết) in northern Vietnam.[citation needed]

Europe

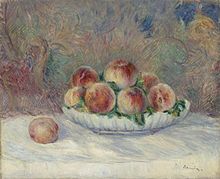

Many famous artists have painted with peach fruits placed in prominence. Caravaggio, Vicenzo Campi, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Henri Fantin-Latour, Severin Roesen, Peter Paul Rubens, and Van Gogh are among the many influential artists who painted peaches and peach trees in various settings.[87][88] Scholars suggest that many compositions are symbolic, some an effort to introduce realism.[89] For example, Tresidder claims[90] the artists of Renaissance symbolically used peach to represent heart, and a leaf attached to the fruit as the symbol for tongue, thereby implying speaking truth from one's heart; a ripe peach was also a symbol to imply a ripe state of good health. Caravaggio's paintings introduce realism by painting peach leaves that are molted, discolored, or in some cases have wormholes – conditions common in modern peach cultivation.[88]

In literature, Roald Dahl named his children's fantasy novel James and the Giant Peach because a peach is "prettier, bigger and squishier than a cherry."[91]

United States

South Carolina named the peach its official fruit in 1984.[92] The peach became the state fruit of Georgia, nicknamed the "Peach State", in 1995.[93] The peach went from feral trees utilized opportunistically to a tended commercial crop in the Southern United States in the 1850s, as the boll weevil attacked regional cotton crops. When Georgia reached peak production in the 1920s, elaborate festivals celebrated the fruit. By 2017, Georgia's production represented 3–5% of the U.S. total.[94][95] Alabama named it the "state tree fruit" in 2006.[96] Delaware's state flower has been the peach blossom since 1995,[97] and peach pie became its official dessert in 2009.[98]

Gallery

-

Peach blossoms

-

Incipient fruit development

-

Peaches on tree

-

Peaches in a basket

Paintings

-

Portrait of Isabella and John Stewart by Charles Willson Peale, 1774

-

Still Life Basket of Peaches by Raphaelle Peale, 1816

-

A Jar of Peaches by Claude Monet c. 1866

-

"Spring 4, peach-blossoms and green pheasants" by Kōno Bairei, 1883

-

Peach (cultivar 'Berry'), watercolour, 1895

References

- ^ "IPNI Plant name Query Results". ipni.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ The Plant List, Prunus persica (L.) Batsch

- ^ a b Yang, Xiaoyan; Zheng, Yunfei; Crawford, Gary W.; Chen, Xugao (2014). "Archaeological Evidence for Peach (Prunus persica) Cultivation and Domestication in China". PLOS ONE. 9 (9): e106595. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6595Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106595. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4156326. PMID 25192436.

- ^ "Almond Tree - Learn About Nature". 27 July 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Haase, Ilka; Brüning, Philipp; Matissek, Reinhard; Fischer, Markus (10 April 2013). "Real-time PCR assays for the quantitation of rDNA from apricot and other plant species in marzipan". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (14): 3414–3418. doi:10.1021/jf3052175. ISSN 1520-5118. PMID 23495652.

- ^ a b c "Frequently Asked Questions". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008.

- ^ Vendramin, Elisa; Pea, Giorgio; Dondini, Luca; Pacheco, Igor; Dettori, Maria Teresa; Gazza, Laura; Scalabrin, Simone; Strozzi, Francesco; Tartarini, Stefano (3 March 2014). "A Unique Mutation in a MYB Gene Cosegregates with the Nectarine Phenotype in Peach". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e90574. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990574V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090574. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3940905. PMID 24595269.

- ^ a b "Production of peaches and nectarines in 2018; Crops/Regions/World/Production Quantity (from pick lists)". United Nations, Food and Agricultural Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "The Average Width of a Peach Tree". SFGate. Hearst Communications Inc. 4 March 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "Indian Peaches Information, Recipes and Facts". Specialtyproduce.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "peach | Fruit, Description, History, Cultivation, Uses, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (2004) Historical Linguistics: An Introduction, second ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, p. 274. ISBN 0-262-53267-0.

- ^ Su, T.; et al. (2016). "Peaches Preceded Humans: Fossil Evidence from SW China". Scientific Reports. 5. Nature Publishing Group: 16794. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516794S. doi:10.1038/srep16794. PMC 4660870. PMID 26610240.

- ^ Thacker, Christopher (1985). The history of gardens. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-520-05629-9.

- ^ Singh, Akath; Patel, R.K.; Babu, K.D.; De, L.C. (2007). "Low chiling peaches". Underutilized and underexploited horticultural crops. New Delhi: New India Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-81-89422-69-1.

- ^ a b c Geissler, Catherine (2009). The New Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-160949-7.

- ^ Layne, Desmond R.; Bassi, Daniele (2008). The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses. CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-386-9.

- ^ Yang, Xiaoyan; Zheng, Yunfei; Crawford, Gary W.; Chen, Xugao (2014). "Archaeological Evidence for Peach (Prunus persica) Cultivation and Domestication in China". PLOS ONE. 9 (9): e106595. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6595Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106595. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4156326. PMID 25192436.

- ^ Fuller, D; Madella, M (2001). "Issues in Harappan Archaeobotany: Retrospect and Prospect". In Settar, S; Korisettar, R (eds.). Indian Archaeology in Retrospect. Vol. II. Protohistory. New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 317–390.

- ^ a b Ensminger, Audrey H. (1994). Foods & nutrition encyclopedia. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8980-1.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food (1 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 588. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- ^ Sadori, Laura; et al. (2009). "The introduction and diffusion of peach in ancient Italy" (PDF). Edipuglia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Noah Blan, 'Charlemagne's Peaches: A Case of Early Medieval European Ecological Adaptation', Early Medieval Europe, 27.4 (2019), 521–45.

- ^ Ibn al-'Awwam, Yaḥyá (1864). Le livre de l'agriculture d'Ibn-al-Awam (kitab-al-felahah) (in French). Translated by J.-J. Clement-Mullet. Paris: A. Franck. pp. 315–319 (ch. 7 – Article 41). OCLC 780050566. (pp. 315–319 (Article XLI)

- ^ "George Minifie". Genforum.genealogy.com. 21 March 1999. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Fogle, H. W. (1965). Peach Production East of the Rocky Mountains. Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. p. 1.

- ^ Swislocki, Mark (2009). Culinary Nostalgia. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 29–64. ISBN 978-0-8047-6012-6.

- ^ Verde, I.; Abbott, A.G.; Scalabrin, S.; Jung, S.; et al. (2013). "The high-quality draft genome of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution". Nature Genetics. 45 (5): 487–494. doi:10.1038/ng.2586. hdl:2434/218547. PMID 23525075.

- ^ Capparelli, Aylen; Lema, Veronica; Giovannetti, Marco; Raffino, Rololfo (2005). "The Introduction of Old World Crops (wheat, barley, and peach) in Andean Argentina during the 16th century A.D." Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 14 (4): 473–475. doi:10.1007/s00334-005-0093-8. JSTOR 23419302. S2CID 129925523. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Jett, Stephen C. (1977). "History of Fruit Tree Raising among the Navajo". Agricultural History. 51 (4): 683. JSTOR 3741756.

- ^ "Peaches". Jefferson Monticello. Jefferson Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Holland-Lulewicz, Jacob; Thompson, Victor; Thompson, Amanda Roberts; Butler, RaeLynn; Chavez, Dario J.; Franklin, Jay; Hunt, Turner; Williams, Mark; Worth, John (20 September 2024). "The initial spread of peaches across eastern North America was structured by Indigenous communities and ecologies". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 8245. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-52597-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11415391.

- ^ "Clinton-Sullavan Expedition of 1779". National Park Service. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Sumiak, Dennis (15 August 2017). "Navajo Will Never Forget the 1864 Scorched Earth Campaign". History Net.

- ^ "Peach tree physiology" (PDF). University of Georgia. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2010.

- ^ Szalay, L.; Papp, J.; Szaóbo, Z. (2000). "Evaluation of frost tolerance of peach varieties in artificial freezing tests". Acta Horticulturae. 538 (538): 407–410. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2000.538.71.

- ^ Chunxian Chen, William R. Okie, Thomas G. Beckman (July 2016). "Peach Fruit Set and Buttoning after Spring Frost". HortScience. 5 (7): 816–821. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.51.7.816.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ European Food Safety Authority (2015). "The 2013 European Union report on pesticide residues in food". EFSA Journal. 13 (3): 4038. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4038. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015.

The highest maximum residue level (MRL) exceedance rate was found for strawberries (2.5% of the samples), followed by lettuce (2.3%), oats (1.3%), peaches (1.1%), and apples (1.0%).

- ^ "Fruit and Nut Varieties for Low-Elevation Sierra Foothills" (PDF). University of California at Davis. November 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Growing Peaches in Maine". Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Peach and Nectarine Culture". University of Rhode Island. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Okie, W.R. (2005). "Varieties – Peaches" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Duke of York' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Peregrine' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica 'Rochester' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Prunus persica var. nectarina 'Lord Napier' (F) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Fairchild, David (1938). The World Was My Garden. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 226.

- ^ "Almonds, Nectarines, Peacherines and Apricots". Koanga Institute. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ Shimabukuro, Betty (7 July 2004). "Mixed marriages: Cross-pollination produces fruit "children" that aren't quite the same as mom and dad". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ Pound, Louise (1920). "Stunts in language". The English Language. 9 (2): 88–95. doi:10.2307/802441. JSTOR 802441.

- ^ Layne, Desmond (2008). The Peach: Botany, Production and uses. CABI. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84593-386-9. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Ingels, Chuck; et al. (2007). The Home Orchard: Growing Your Own Deciduous Fruit and Nut Trees. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b McCraw, Dean. "Planting and Early Care of the Peach Orchard". Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Wer frisst Pfirsich-Blütenknopsen?" [Who eats peach blossom buds?]. Garten-pur.de (in German). 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "UC Pest Management Guidelines". UC Davis. 10 September 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Trainotti, L.; Tadiello, A.; Casadoro, G. (2007). "The involvement of auxin in the ripening of climacteric fruits comes of age: The hormone plays a role of its own and has an intense interplay with ethylene in ripening peaches". Journal of Experimental Botany. 58 (12): 3299–3308. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm178. PMID 17925301.

- ^ Ziosi, V.; Bregoli, A. M.; Fiori, G.; Noferini, M.; Costa, G. (2007). "1-MCP effects on ethylene emission and fruit quality traits of peaches and nectarines". Advances in Plant Ethylene Research. p. 167. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6014-4_38. ISBN 978-1-4020-6013-7. S2CID 81245874.

- ^ "Prunus persica, peach, nectarine". GeoChemBio.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Healthy and Sustainable Food". The Center for Health and the Global Environment. Harvard Medical School. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ a b Kathryn C. Taylor (15 August 2003). "Peaches". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Fair, John D. (2002). "The Georgia Peach and the Southern Quest for Commercial Equity and Independence, 1843–1861". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 86 (3): 372. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Fresh Peach and Nectarine Productions in Latin America in 2021 by country". Statista.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Nutrition Facts for Nectarines, raw, per 100 g". Conde Nast, USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Glycemic index and glycemic load for 100+ foods". Harvard Health Publications, Harvard University School of Medicine. 27 August 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ "Health Benefits of Peaches: A Delicious Summer Fruit (Rutgers NJAES)". njaes.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Gil, M. I.; Tomás-Barberán, F. A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Kader, A. A. (2002). "Antioxidant capacities, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and vitamin C contents of nectarine, peach, and plum cultivars from California". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 50 (17): 4976–4982. doi:10.1021/jf020136b. PMID 12166993.

- ^ Cheng, Guiwen W. & Crisosto, Carlos H. (1995). "Browning Potential, Phenolic Composition, and Polyphenoloxidase Activity of Buffer Extracts of Peach and Nectarine Skin Tissue". J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 120 (5): 835–838. doi:10.21273/JASHS.120.5.835.

- ^ Infante, Rodrigo; Contador, Loreto; Rubio, Pía; Aros, Danilo & Peña-Neira, Álvaro (2011). "Postharvest sensory and phenolic characterization of 'Elegant Lady' and 'Carson' peaches" (PDF). Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research. 71 (3): 445–451. doi:10.4067/S0718-58392011000300016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b Chang, S; Tan, C; Frankel, EN; Barrett, DM (2000). "Low-density lipoprotein antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds and polyphenol oxidase activity in selected clingstone peach cultivars". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (2): 147–51. doi:10.1021/jf9904564. PMID 10691607.

- ^ Cevallos-Casals, B. V. A.; Byrne, D.; Okie, W. R.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. (2006). "Selecting new peach and plum genotypes rich in phenolic compounds and enhanced functional properties". Food Chemistry. 96 (2): 273–280. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.032.

- ^ Andreotti, C.; Ravaglia, D.; Ragaini, A.; Costa, G. (2008). "Phenolic compounds in peach (Prunus persica) cultivars at harvest and during fruit maturation". Annals of Applied Biology. 153: 11–23. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00234.x.

- ^ a b Lee, SH; Oh, A; Shin, SH; Kim, HN; Kang, WW; Chung, SK (2017). "Amygdalin contents in peaches at different fruit development stages". Preventive Nutrition and Food Science. 22 (3): 237–240. doi:10.3746/pnf.2017.22.3.237. ISSN 2287-1098. PMC 5642807. PMID 29043223.

- ^ a b Cho HJ, Do BK, Shim SM, Kwon H, Lee DH, Nah AH, Choi YJ, Lee SY (2013). "Determination of cyanogenic compounds in edible plants by ion chromatography". Toxicol Res. 29 (2): 143–7. doi:10.5487/TR.2013.29.2.143. PMC 3834451. PMID 24278641.

- ^ "Laetrile (Amygdalin)". US National Cancer Institute. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Besler, M.; Cuesta Herranz, Javier & Fernandez-Rivas, Montserrat (2000). "Allergen Data Collection: Peach (Prunus persica)". Internet Symposium on Food Allergens. 2 (4): 185–201. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009.

- ^ Sánchez G, Besada C, Badenes ML, Monforte AJ, Granell A (2012). "A non-targeted approach unravels the volatile network in peach fruit". PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e38992. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738992S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038992. PMC 3382205. PMID 22761719.

- ^ Doré S.J., Henry (1914). Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Vol. V. Translated by Kennelly, M. Tusewei Press, Shanghai. p. 505. ISBN 9781462268412.

- ^ a b c Simoons, Frederick J. (1991) Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry, p. 218, ISBN 0-8493-8804-X.

- ^ "TCM: Peach kernels" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in early taoist religion. SUNY Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7914-3955-5. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016.

- ^ 한국에서의 복숭아 재배 [Peach cultivation in Korea] (in Korean). Nate / Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ 복숭아 [Peach] (in Korean). Nate / Encyclopedia of Korean culture. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "The world's sweetest peach costs $7,000. So is it worth the price tag?". www.abc.net.au. 17 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Torpy, Janet M. (2010). "Still Life With Peaches". JAMA. 303 (3): 203. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1853. PMID 20085943.

- ^ a b Jules Janick. "Caravaggio's Fruit: A Mirror on Baroque Horticulture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ de Groft, Aaron H. (2006). "Caravaggio – Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge" (PDF). Papers of the Muscarelle Museum of Art, Volume 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ^ Tresidder, Jack (2004). 1,001 Symbols: An Illustrated Guide to Imagery and Its Meaning. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-4282-2.

- ^ "Roald Dahl Day: Seven fantastic facts about the author". BBC. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Plants & Edibles, South Carolina Legislature Online, retrieved 29 May 2019

- ^ "State Fruit". Georgia State Symbols. Georgia Secretary of State. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Okie, William Thomas (14 August 2017), "The Fuzzy History of the Georgia Peach", Smithsonian.com, retrieved 29 May 2019

- ^ Mackie, Matt (1 November 2018), "Is Georgia really the Peach State?", wxga.com, retrieved 29 May 2019

- ^ "State Tree Fruit of Alabama". Alabama Emblems, Symbols and Honors. Alabama Department of Archives and History. 20 April 2006. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Delaware State Plants". Delaware.gov. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Delaware Miscellaneous Symbols". Delaware.gov. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

Further reading

- Okie, William Thomas. The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South (Cambridge Studies on the American South, 2016).