Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted | |

|---|---|

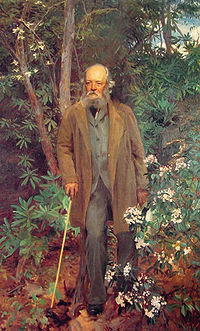

Olmsted in 1893; engraving after a photograph | |

| Born | April 26, 1822[1] Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | August 28, 1903 (aged 81) Belmont, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Old North Cemetery, Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Landscape architect |

| Notable work | New York City Park |

| Spouse | Mary Cleveland Perkins |

| Children | John Charles, Charlotte, Owen, and Marion, and Frederick Law Jr. |

| Parent(s) | John and Charlotte Olmsted |

| Signature | |

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the United States. Olmsted was famous for co-designing many well-known urban parks with his partner Calvert Vaux. Olmsted and Vaux's first project was Central Park in New York City, which led to many other urban park designs. These included Prospect Park in Brooklyn; Cadwalader Park in Trenton, New Jersey; and Forest Park in Portland, Oregon.[2] In 1883, Olmsted established the preeminent landscape architecture and planning consultancy of the late 19th-century United States, which was carried on and expanded by his sons, Frederick Jr. and John C., under the name Olmsted Brothers.[3]

Other projects that Olmsted was involved in include the country's first and oldest coordinated system of public parks and parkways in Buffalo, New York; the country's oldest state park, the Niagara Reservation in Niagara Falls, New York; one of the first planned communities in the United States, Riverside, Illinois; Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Quebec; The Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut; Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut; Waterbury Hospital in Waterbury, Connecticut; the Emerald Necklace in Boston, Massachusetts; Highland Park in Rochester, New York; the Grand Necklace of Parks in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Cherokee Park and parks and parkway system in Louisville, Kentucky; Walnut Hill Park in New Britain, Connecticut; the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina; the master plans for the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Maine, Stanford University near Palo Alto, California, Mount Holyoke College, The Lawrenceville School; and Montebello Park in St. Catharines, Ontario. In Chicago his projects include Jackson Park, Washington Park, the main park ground for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, the southern portion of Chicago's emerald necklace boulevard ring, and the University of Chicago campus. In Washington, D.C., he worked on the landscape surrounding the United States Capitol building.

The quality of Olmsted's landscape architecture was recognized by his contemporaries, who showered him with prestigious commissions. Daniel Burnham said of him, "He paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountainsides and ocean views...."[4] His work, especially in Central Park, set a standard of excellence that continues to influence landscape architecture in the United States. He was an early and important activist in the conservation movement, including in his work at Niagara Falls, the Adirondack region of upstate New York, and the National Park system. As head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, he also played a major role in organizing and providing medical services to the Union Army during the Civil War.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]

Olmsted was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on April 26, 1822. His father, John Olmsted, was a prosperous merchant who took a lively interest in nature, people, and places; Frederick Law and his younger brother, John Hull Olmsted, also showed this interest. His mother, Charlotte Law (née Hull) Olmsted, died from an overdose before his fourth birthday in 1826.[6][7] His father remarried in 1827 to Mary Ann Bull, who shared her husband's strong love of nature and had perhaps a more cultivated taste. Their children were Charlotte, Mary, Owen, Bertha, Ada, and Albert Olmsted.[7] The Olmsted ancestors arrived in the early 1600s from Essex, England.[8]

When he was almost ready to enter Yale College at a young age, sumac poisoning weakened his eyes, so he abandoned college plans. After working as an apprentice seaman, merchant, and journalist, he settled on a 125 acres (51 ha) farm in January 1848 on the south shore of Staten Island. His father helped him acquire this farm, and he renamed it from Akerly Homestead to Tosomock Farm. It was later renamed "The Woods of Arden" by owner Erastus Wiman. The house in which Olmsted lived still stands at 4515 Hylan Boulevard, near Woods of Arden Road.

Career

[edit]Journalism

[edit]Olmsted had a significant career in journalism. In 1850 he traveled to England to visit public gardens, where he was greatly impressed by Joseph Paxton's Birkenhead Park. He subsequently wrote and published Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England in 1852.[9] This supported his getting additional work. His visit to Birkenhead Park inspired his later contribution to the design of Central Park in New York City.[10]

Interested in the slave economy, he was commissioned by the New York Daily Times (now The New York Times) to embark on an extensive research journey through the American South and Texas from 1852 to 1857. His dispatches to the Times were collected into three volumes (A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (1856), A Journey Through Texas (1857), A Journey in the Back Country in the Winter of 1853–4 (1860).

These are considered vivid first-person accounts of the antebellum South. A one-volume abridgment, Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom (1861), was published in England during the first six months of the American Civil War, at the suggestion of Olmsted's English publisher.[11][12][13]

To this, he wrote a new introduction (on "The Present Crisis"). He stated his views on the effect of slavery on the economy and social conditions of the southern states:

My own observation of the real condition of the people of our Slave States, gave me ... an impression that the cotton monopoly in some way did them more harm than good; and although the written narration of what I saw was not intended to set this forth, upon reviewing it for the present publication, I find the impression has become a conviction.

He argued that slavery had made the slave states inefficient (a set amount of work took 4 times as long in Virginia as in the North) and backward both economically and socially. He said that the profits of slavery were enjoyed by no more than 8,000 owners of large plantations; a somewhat larger group had about the standard of living of a New York City policeman, but the proportion of the free white men who were as well-off as a Northern working man was small. Slavery meant that 'the proportion of men improving their condition was much less than in any Northern community; and that the natural resources of the land were strangely unused, or were used with poor economy.'

He thought that the lack of a Southern white middle class and the general poverty of lower-class whites prevented the development of many civil amenities that were taken for granted in the North.

The citizens of the cotton States, as a whole, are poor. They work little, and that little, badly; they earn little, they sell little; they buy little, and they have little – very little – of the common comforts and consolations of civilized life. Their destitution is not material only; it is intellectual and it is moral ... They were neither generous nor hospitable and their talk was not that of evenly courageous men.[14]

Between his travels in Europe and the South, Olmsted served as an editor for Putnam's Magazine for two years[15] and as an agent with Dix, Edwards and Co., before the company's insolvency during the Panic of 1857. Olmsted provided financial support for, and occasionally wrote for, the magazine The Nation, which was founded in 1865.[15] "Olmsted spent much of his free time working without pay as an editorial assistant to [the magazine's first editor, Edwin L.] Godkin. It was a labor of love."[16]

New York City's Central Park

[edit]

Andrew Jackson Downing, the landscape architect from Newburgh, New York, was one of the first to propose developing New York City's Central Park in his role as publisher of The Horticulturist magazine. A friend and mentor to Olmsted, Downing introduced him to the English-born architect Calvert Vaux, whom Downing had brought to the U.S. as his architectural collaborator. After Downing died in July 1852 in a widely publicized fire on the Hudson River steamboat Henry Clay, Olmsted and Vaux entered the Central Park design competition together, against Egbert Ludovicus Viele among others. Vaux had invited the less experienced Olmsted to participate in the design competition with him, having been impressed with Olmsted's theories and political contacts. Prior to this, in contrast with the more experienced Vaux, Olmsted had never designed or executed a landscape design.

Their Greensward Plan was announced in 1858 as the winning design. On his return from the South, Olmsted began executing their plan almost immediately. Olmsted and Vaux continued their informal partnership to design Prospect Park in Brooklyn from 1865 to 1873.[17] That was followed by other projects. Vaux remained in the shadow of Olmsted's grand public personality and social connections.

The design of Central Park embodies Olmsted's social consciousness and commitment to egalitarian ideals. Influenced by Downing and his observations regarding social class in England, China, and the American South, Olmsted believed that the common green space must always be equally accessible to all citizens, and was to be defended against private encroachment. This principle is now fundamental to the idea of a "public park", but was not assumed as necessary then. Olmsted's tenure as Central Park commissioner was a long struggle to preserve that idea.[18]

U.S. Sanitary Commission

[edit]In 1861, Olmsted took leave as director of Central Park to work in Washington, D.C., as Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the Red Cross. He tended to the wounded during the American Civil War. In 1862, during Union General George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign, he headed the medical effort for the sick and wounded at White House plantation in New Kent County, which had a boat landing on the Pamunkey River.

He was one of the six founding members of the Union League Club of New York.

He helped to recruit and outfit three African-American regiments of the United States Colored Troops in New York City.[citation needed] He contributed to organizing a Sanitary Fair, which raised one million dollars for the United States Sanitary Commission.

He worked for the Sanitary Commission to the point of exhaustion: "Part of the problem was his need to maintain control over all aspects of the commission's work. He refused to delegate and he had an appetite for authority and power."[19] By January 1863 a friend wrote: "Olmsted is in an unhappy, sick, sore mental state ... He works like a dog all day and sits up nearly all night ... works with steady, feverish intensity till four in the morning, sleeps on a sofa in his clothes, and breakfasts on strong coffee and pickles!!!"[19] His overwork and lack of sleep led to his being in a perpetual state of irritability, which wore on the people with whom he worked: "Exhausted, ill and having lost the support of the men who put him in charge, Olmsted resigned on Sept. 1, 1863." Yet within a month he was on his way to California.[19]

Gold mining project in California

[edit]In 1863, Olmsted went west to become the manager of the newly established Rancho Las Mariposas–Mariposa gold mining estate in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California.[20] The estate had been sold by John C. Fremont to New York banker, Morris Ketchum, in January of that same year. The mine was unsuccessful. "By 1865, the Mariposa Company was bankrupt, Olmsted returned to New York, and the land and mines were sold at a sheriff's sale."[21]

In 1865, he was appointed to the first board of commissioners for managing the newly established Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove land grants.[22]

U.S. park designer

[edit]In 1865, he and Vaux formed Olmsted, Vaux & Co. When Olmsted returned to New York, he and Vaux designed Prospect Park; the planned Chicago suburb of Riverside, Illinois; the park system for Buffalo, New York; Milwaukee's grand necklace of parks; and the Niagara Reservation at Niagara Falls and Belle Isle in Detroit.

Olmsted conceived of entire systems of parks and interconnecting parkways to connect certain cities to green spaces. Some of the best examples of the scale on which he worked are the park system designed for Buffalo, one of the largest projects; the system he designed for Milwaukee, and the park system designed for Louisville, Kentucky, which was one of only four completed Olmsted-designed park systems in the world.[citation needed]

Olmsted was a frequent collaborator with architect Henry Hobson Richardson, for whom he devised the landscaping schemes for half a dozen projects, including Richardson's commission for the Buffalo State Asylum.[23] In 1871, Olmsted and Vaux designed the grounds for the Hudson River State Hospital for the Insane in Poughkeepsie.[24]

In 1883, Olmsted established what is considered to be the first full-time landscape architecture firm in Brookline, Massachusetts. He called the home and office compound Fairsted. It is now the restored Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. From there Olmsted designed Boston's Emerald Necklace, the campuses of Wellesley College, Smith College, Stanford University and the University of Chicago, as well as the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, among many other projects.

Olmsted was one of the planners of the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., which was founded in 1889.[25]

Conservationist

[edit]Olmsted was an important early leader of the conservation movement in the United States. An expert on California, he was likely one of the gentlemen "of fortune, of taste and of refinement" who proposed, through Senator John Conness, that Congress designate Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove as public reserves.[26] This was the first land set aside by Congress for public use. Olmsted served a one-year appointment on the Board of Commissioner of the state reserve, and his 1865 report to Congress on the board's recommendations laid an ethical framework for the government to reserve public lands, to protect their "value to posterity". He described the "sublime" and "stately" landscape, emphasizing that the value of the landscape was not in any one individual waterfall, cliff, or tree, but in the "miles of scenery where cliffs of awful height and rocks of vast magnitude and of varied and exquisite coloring, are banked and fringed and draped and shadowed by the tender foliage of noble and lovely trees and bushes, reflected from the most placid pools, and associated with the most tranquil meadows, the most playful streams, and every variety of soft and peaceful pastoral beauty".[27]

In the 1880s, he was active in efforts to conserve the natural wonders of Niagara Falls, threatened with industrialization by the building of electrical power plants. At the same time, he campaigned to preserve the Adirondack region in upstate New York. He was one of the founders of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1898.[28]

Olmsted was also known to oppose park projects on conservationist grounds. In 1891, Olmsted refused to develop a plan for Presque Isle Park in Marquette, Michigan, saying that it "should not be marred by the intrusion of artificial objects".[29]

Legacy

[edit]

After Olmsted's retirement and death, his sons John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., continued the work of their firm, doing business as the Olmsted Brothers. The firm lasted until 1980. Many works by the Olmsted sons are mistakenly credited to Frederick Law Olmsted today. For instance, the Olmsted Brothers firm did a park plan for Portland, Maine, in 1905, creating a series of connecting parkways between existing parks and suggesting improvements to those parks. The oldest of these parks, Deering Oaks, had been designed by City Engineer William Goodwin in 1879 but is today frequently described as a Frederick Law Olmsted-designed park.

A residence hall at the University of Hartford was named in his honor. Olmsted Point, located in Yosemite National Park,[30] was named after Olmsted and his son Frederick.[31]

The Olmsted Center located in Queens, NY pays an homage to Frederick Law Olmsted.

The Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site is located in Brookline, Massachusetts in his former home. Olmsted is known as the "father of American Landscape Architecture".[32]

Personal life

[edit]On June 13, 1859, Olmsted married Mary Cleveland (Perkins) Olmsted, the widow of his brother John, who died in 1857. Daniel Fawcett Tiemann, the mayor of New York, officiated the wedding. Olmsted adopted Mary's three children (his nephews and niece), John Charles Olmsted (born 1852), Charlotte Olmsted (born 1855), and Owen Frederick Olmsted (born 1857).[7]

Frederick and Mary also had two children together who survived infancy: a daughter, Marion (born October 28, 1861), and a son Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (born July 24, 1870). Their first child, John Theodore Olmsted, was born on June 13, 1860, and died in infancy.[33][34]

In recognition of his services during the Civil War, Olmsted was elected a Third Class member of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) on May 2, 1888, and was assigned insignia number 6345. Olmsted's election to MOLLUS is significant in that he was one of the few civilians elected to membership in an organization composed almost exclusively of military officers and their descendants.[35] In 1891 he joined the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution by right of his descent from his grandfather Benjamin Olmsted who served in the 4th Connecticut Regiment in 1775.[36]

In 1895, senility forced Olmsted to retire. By 1898 he moved to Belmont, Massachusetts, and took up residence as a patient at the McLean Hospital, for whose grounds he had submitted a design which was never executed. He remained there until he died in 1903.

Olmsted's principles of design

[edit]Drawing influences from English landscape and gardening,[37] Olmsted emphasized design that encourages the full use of the naturally occurring features of a given space,[38] its "genius"; the subordination of individual details to the whole so that decorative elements do not take precedence, but rather the whole space is enhanced; concealment of design, design that does not call attention to itself; design that works on the unconscious to produce relaxation; and utility or purpose over ornamentation. A bridge, a pathway, a tree, a pasture: any and all elements are brought together to produce a particular effect.

Olmsted designed primarily in pastoral and picturesque styles, each to achieve a particular effect. The pastoral style featured vast expanses of green with small lakes, trees, and groves and produced a soothing, restorative effect on the viewer. The picturesque style covered rocky, broken terrain teeming with shrubs and creepers, to express nature's richness. The picturesque style played with light and shade to lend the landscape a sense of mystery.

Scenery was designed to enhance the sense of space: indistinct boundaries using plants, brush, and trees as opposed to sharp ones; the interplay of light and shadow close up, and blurred detail farther away. He employed a vast expanse of greenery at the end of which would lie a grove of yellow poplar; a path that winds through a bit of landscape and intersects with others, dividing the terrain into triangular islands of successive new views.

Subordination strove to use all objects and features in the service of the design and its intended effect. It can be seen in the subtle use of naturally occurring plants throughout the park. Non-native species planted for the sake of their own uniqueness was seen as defeating the purpose of design, as that very uniqueness would draw attention to itself where the intention is to enable relaxation: utility above all else was an objective. Separation applied to areas designed in different styles and different uses enhancing safety and reducing distraction. A key feature of Central Park is the use of sunken roadways which traverse the park and are specifically dedicated to vehicles as opposed to the winding pathways designated specifically for pedestrians.

An example of this mix of principles is seen in the Central Park Mall, a large promenade leading to the Bethesda Terrace, and the single formal feature in Olmsted and Vaux's original naturalistic design. The designers wrote that a "'grand promenade' was an 'essential feature of a metropolitan park'";[39] however, its formal symmetry, its style, although something of an aberration, was designed to be subordinate to the natural view surrounding it. Wealthy passengers were let from their carriages at its south end. The carriage would then drive around to the Terrace, which overlooked the Lake and Ramble to pick them up, saving them the trouble of needing to double back on foot. The Promenade was lined with slender elms and offered views of Sheep Meadow.

Affluent New Yorkers, who rarely walked through the park, mixed with the less well-to-do in the Terrace areas, and all enjoyed an escape from the hustle and bustle of the surrounding city. However, the most wealthy among them employed the firm to landscape their country estates in a similar fashion for their private enjoyment, such as that of Frederick T. van Beuren Jr. in New Jersey. He is a descendant of a Dutch physician who settled in Manhattan in 1700 and whose family members became prominent property owners in the city and various other locations. Initially, that country estate was one of several self-sufficient retreats from Manhattan held by the family that included a supporting farm for produce, livestock, and a livery as well as several houses for permanent staff. The estate later became a more permanent residence as van Beuren's career shifted to founding a hospital in the growing community nearby. At that time the shingled structure in New Vernon was renovated into a brick structure that is described as one of the notable mansions of the area.[40] At the time of the renovation, the mature landscape plan for the residence was not altered. A widening of Spring Valley Road during the late twentieth century did eliminate some Olmsted landscaping that included a cascading bank of native ferns lining a roadside stretch of the property that extended along the road from Blackberry Lane to the eponymous van Beuren Road that divided the family property from its northern boundary to its southern boundary at Blue Mill Road.

In popular culture

[edit]- In June 2022, a baby giraffe at the Seneca Park Zoo in Rochester, New York, was named Olmsted, in recognition of the designer of Seneca Park and other parks in Rochester.[41]

See also

[edit]- List of Olmsted works

- Frederick E. Olmsted

- Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

- Charles Loring Brace

- Landscape designer

- History of gardening

- Devil in the White City

References

[edit]- ^ A celebration of the life and work of Frederick Law Olmsted – Biography Page.

- ^ "F. L. Olmsted is Dead; End Comes to Great Landscape Architect at Waverly, Mass. Designer of Central and Prospect Parks and Other Famous Garden Spots of American Cities" (PDF). New York Times. August 29, 1903. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 500. ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ Martin, John Stuart (October 1964). "He Paints With Lakes And Wooded Slopes ...". American Heritage. 15 (6).

- ^ Robert Muccigrosso, ed., Research Guide to American Historical Biography.

- ^ Martin, Justin (2011). Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. Hachette Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-306-81984-1. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Olmsted Family | Articles and Essays | Frederick Law Olmsted Papers | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ Olmsted, Henry King; Ward, George K. (1912). Genealogy of the Olmsted family in America. Quintin Publications. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-58211-670-9. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Homsy, Bryn (2001). "Frederick Law Olmsted". Historic Gardens Review (9): 2–7. ISSN 1461-0191. JSTOR 44791222.

- ^ Olmsted, Frederick Law (1852). Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England. George E. Putnam. p. 83. OCLC 3900449.

- ^ Cf. Wilson, p. 220. "At the beginning of the Civil War, it was suggested by Olmsted's English publisher that a one-volume abridgment of all three of these books would be of interest to the British public, and Olmsted, then busy with Central Park, arranged to have this condensation made by an anti-slavery writer from North Carolina. Olmsted himself contributed to a new introduction on The Present Crisis."

- ^ Stampp, Kenneth M. (1953). "review of The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller's Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States. Based upon Three Former Volumes of Journeys and Investigations by the Same Author by Frederick Law Olmsted; edited, with an introduction by Arthur M. Schlesinger". The American Historical Review. doi:10.1086/ahr/59.1.141. vol. 1 of 1861 edition vol. 2 of 1861 edition

- ^ Woody, Robert Hilliard (1955). "review of The Cotton Kingdom by Frederick Law Olmsted; edited, with an introduction, by Arthur M. Schlesinger". South Atlantic Quarterly. 54: 164–165. doi:10.1215/00382876-54-1-164. S2CID 257878647.

- ^ Olmsted, Frederick Law, The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller's Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States. Based Upon Three Former Volumes of Journeys and Investigations, Mason Brothers, 1862.

- ^ a b Filler, Martin (November 5, 2015). "America's Green Giant". New York Review of Books. 62 (17). Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Lee, Olmsted's America, p. 147.

- ^ Lancaster, Clay (1972). Handbook of Prospect Park. Long Island University Press. pp. 51–66. ISBN 0-913252-06-9. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009.

- ^ Kalfus 1991, pp. 308ff

- ^ a b c Masur, Louis P. (July 9, 2011). "Olmsted's Southern Landscapes". New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Olmsted Introduction". Archived from the original on October 11, 1999.

- ^ Chamberlain, Newell D. (1936). The Call of Gold: True Tales on the Gold Road to Yosemite. Mariposa, California: Gazette Press.

- ^ "Yosemite History: Frederick Law Olmsted, Landscape Architect". Yosemite National Park. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Carla Yanni, The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States, University of Minnesota Press, 2007, pp. 127–139.

- ^ Farrell, Barbara Gallo (August 14, 2019). "Through photographs, history of 'Hudson River State Hospital' unveiled". www.poughkeepsiejournal.com. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Smithsonian National Zoological Park

- ^ Laura Wood Roper. "FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted".

- ^ Frederick Law Olmsted, "The Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove".

- ^ Albert Fein, Frederick Law Olmsted and the American Environmental Tradition (1972).

- ^ Martin, Justin (September 2, 2011). "Jewels of Olmsted's Unspoiled Midwest". The New York Times.

- ^ "Olmsted Point". Russ Cary. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ^ "Hundreds Celebrate Completion of Facelift to Yosemite's Dramatic Olmsted Point Overlook". National Park Service. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site—Massachusetts Conservation: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". Archived from the original on May 2, 2015.

- ^ Witold Rybezynski, A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century, Scribner, New York, 1999.

- ^ Frederick Law Olmsted; Theodora Kimball Hubbard (1922). Frederick Law Olmsted, Landscape Architect, 1822–1903. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 78–.

- ^ 1912 Register of the Massachusetts Commandery of MOLLUS.

- ^ Yearbook of the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution 1897, 1898 & 1899, p. 587.

- ^ Walter Rogers; Michaal Dollin (2010). The Professional Practice of Landscape Architecture: A Complete Guide to Starting and Running Your Own Firm. John Wiley & Sons. p. 19. ISBN 9780470902424.

- ^ Kalfus 1991, pp. 196, 313

- ^ Rosenzweig & Blackmar 1992, p. 133

- ^ "Rae, John W., Images of America: Mansions of Morris County, Charleston, South Carolina, Arcadia Press presented at Owners of mansions in Morristown, Madison, and the surrounding area in Brief History of Morris County prepared by the county".

- ^ Freile, Victoria E. "Baby giraffe at Seneca Park Zoo named after park designer". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beveridge, Charles E; Paul Rocheleau (October 1998). Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing the American Landscape. New York: Universe Publishing. ISBN 0-7893-0228-4.

- Guide to Biltmore Estates. Asheville, North Carolina: The Biltmore Company. 2003.

- Diamant, Rolf and Carr, Ethan (2022). Olmsted and Yosemite: Civil War, Abolition, and The National Park Idea. Amherst, Massachusetts: Library of American Landscape History ISBN 9781952620348

- Drabelle, Dennis (2021). The Power of Scenery: Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origin of National Parks. Bison Books. ISBN 978-1496220776

- Horwitz, Tony (2019). Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1101980309. Review by David W. Blight.

- Kalfus, Melvin (1991). Frederick Law Olmsted: The Passion of a Public Artist. The American Social Experience. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4618-9. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- Hall, Lee (1995). Olmsted's America: An "Unpractical" Man and His Vision of Civilization. Boston, MA: Bullfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-1998-7.

- Martin, Justin (2011). Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81881-3

- Muccigrosso, Robert, ed. (1988). Research Guide to American Historical Biography 5:2666-74

- Ott, Jennifer. Olmsted in Seattle: Creating a Park System for a Modern City (Seattle: History Link and Documentary Media, 2019) online review

- Roper, Laura Wood (1973). FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted. online edition

- Rosenzweig, Roy & Blackmar, Elizabeth (1992). The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9751-5.

- Rybczynski, Witold (June 1999). A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and North America in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-82463-9.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Sr. "Was Olmsted an Unbiased Critic of the South?" Journal of Negro History (1952), 37#2 pp. 173–187 in JSTOR

- Sears, Stephen W. (1992). To the Gates of Richmond: the Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor and Fields ISBN 0-89919-790-6

- Wilson, Edmund (1962). Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, New York: Oxford University Press. Chapter VI is titled "Northerners in the South: Frederick L. Olmsted, John T. Trowbridge". Reviewing Patriotic Gore, David W. Blight wrote, "But who knew that the travel writings of Frederick Law Olmsted, who was much more famous as the designer of Central Park in New York, or the poet, John T. Trowbridge, provided such vivid depictions of slavery and the ruined South both before and after the war?" Slate, March 22, 2012.

Primary sources

[edit]- Beveridge, Charles E., ed., Lauren Meier, ed., and Irene Mills, ed. Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015. xvi, 429 pp.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1856). A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States; With Remarks on Their Economy (1856). Available online from the Internet Archive.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1857). A Journey through Texas, or, A saddle-trip on the southwestern frontier: with a statistical appendix. Available online from the University of North Texas.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1860). A Journey in the Back Country

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1861). The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller's Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States. Based upon three former volumes of journeys and investigations by the same author. (2 vols.). New York: Mason Brothers The one-volume British edition was titled Journeys and explorations in the cotton kingdom. A traveller's observations on cotton and slavery in the American slave states. Based upon three former volumes of journeys and investigations by the same author. London: S. Low, Son & Co. This book is an abridgment of "his three earlier volumes, 'A Journey in the Seaboard [Slave] States' (1856), 'A Journey Through Texas' (1857) and 'A Journey in the Back Country' (1860)." Masur, Louis P., "Olmsted's Southern Landscapes," The New York Times, July 9, 2011

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1861–1863). U.S. Sanitary Commission reports attributed to Olmsted. Available online from the Internet Archive.

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (1865). "Yosemite Valley" and the "Mariposa Big Tree Grove" in the Statutes of California. The National Park Service Archived August 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Olmsted, Frederick Law (August 1865), Preliminary Report upon the Yosemite and Big Tree Grove, in Diamant, Rolf and Carr, Ethan (2022). Olmsted and Yosemite: Civil War, Abolition, and The National Park Idea, pp. 121–149.

- Robert Twombly, ed. (2010): "Frederick Law Olmsted: Essential Texts", W. W. Norton & Company, New York.

External links

[edit]- Frederick Law Olmsted: A bibliography by the Buffalo History Museum

- The National Association for Olmsted Parks

- The Frederick Law Olmsted Society of Riverside

- The Olmsted Plan KCET Departures Olmsted Plan

- Olmsted and America's Urban Parks Archived March 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 2010 documentary; supplemental materials at OlmstedFilm.org

- Booknotes interview with Witold Rybczynski on A Clearing in the Distance, October 17, 1999.

- Frederick Law Olmsted Explore Capitol Hill

- Fine Arts Garden Archived May 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Cleveland Museum of Art

- Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America Archived May 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (2014 documentary)

- Works by Frederick Law Olmsted at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Frederick Law Olmsted at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1822 births

- 1903 deaths

- American landscape and garden designers

- American landscape architects

- American urban planners

- Druid Hills, Georgia

- McLean Hospital people

- The Nation (U.S. magazine) people

- People from Belmont, Massachusetts

- Artists from Staten Island

- People of the American Civil War

- Phillips Academy alumni

- Russell Sage Foundation

- Writers from Hartford, Connecticut

- Central Park

- American people of English descent