Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort | |

|---|---|

Historic District, downtown Church of the Good Shepherd Downtown at night Frankfort in 2009 | |

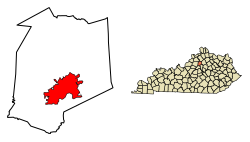

Location of Frankfort in Franklin County, Kentucky | |

| Coordinates: 38°12′N 84°52′W / 38.200°N 84.867°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kentucky |

| County | Franklin |

| Established | 1786 |

| Incorporated | February 28, 1835 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission/Manager |

| • Mayor | Layne Wilkerson[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 15.07 sq mi (39.03 km2) |

| • Land | 14.77 sq mi (38.25 km2) |

| • Water | 0.30 sq mi (0.78 km2) |

| Elevation | 505 ft (154 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 28,602 |

• Estimate (2022)[4] | 28,391 |

| • Density | 1,900/sq mi (730/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 40601-40604, 40618-40622 |

| Area code | 502 |

| FIPS code | 21-28900 |

| GNIS feature ID | 517517[3] |

| Website | City website |

Frankfort is the capital of the U.S. state of Kentucky and the seat of Franklin County.[5] It is a home rule-class city.[6] The population was 28,602 at the 2020 census, making it the thirteenth-most populous city in Kentucky.[7] Located along the Kentucky River, Frankfort is the principal city of the Frankfort, Kentucky Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Franklin and Anderson counties.

Before Frankfort was founded, the site was a ford across the Kentucky River, along one of the great buffalo trails used as highways in colonial America.[8] English explorers first visited the area in the 1750s. The site evidently received its name after an incident in 1780, when pioneer Stephen Frank was killed in a skirmish with Native Americans; the crossing was named "Frank's Ford" in his memory.[8] In 1786, the Virginia legislature designated 100 acres (40 hectares) as the town of Frankfort and, after Kentucky became a state in 1792, it was chosen as capital.[8][9]

The city is located in the inner Bluegrass region of Kentucky.[10] The Kentucky River flows through the city, making a turn as it passes through the center of town; the Downtown and South Frankfort districts are opposite one another on each side of the river. The suburban areas on either side of the river valley are known as East and West Frankfort. Frankfort has four distinct seasons; winter is normally cool with some snowfall, while summers are hot and humid.[11][12]

Because of the city's location on the Kentucky River, it has flooded many times, with the two highest recorded floods occurring in 1937 and 1978.[10] The North Frankfort levee, finished in 1969, and the South Frankfort floodwall, built in the 1990s, were constructed for flood protection.[10] Five bridges cross the river in downtown Frankfort, including the St. Clair Street bridge and Capitol Avenue bridge.[10] Notable locations include the Kentucky State Capitol building, the Capital City Museum,[13] and Fort Hill, a promontory with a view of downtown.

As of 2016, the city's largest industry was public administration with 28% of the workforce.[14] Manufacturing totaled over 12% of the workforce.[14] Frankfort is adjacent to Interstate 64, and Interstate 75 is nearby; general aviation access is via the Capital City Airport, and commercial air travel is available through Blue Grass Airport in Lexington.[14]

History

[edit]Pre-1900

[edit]The town of Frankfort likely received its name from an event that took place in the 1780s. Native Americans attacked a group of early European colonists from Bryan Station, who were on their way to make salt at Mann's Lick in Jefferson County. Pioneer Stephen Frank was killed at the Kentucky River and the settlers thereafter called the crossing "Frank's Ford". This name was later elided to Frankfort.[15]

In 1786, James Wilkinson purchased a 260-acre (110-hectare) tract of land on the north side of the Kentucky River, which developed as downtown Frankfort. He was an early promoter of Frankfort as the state capital. Wilkinson felt Frankfort would be a center of transportation using the Kentucky River to ship farm produce to the Ohio River and then to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans.

After Kentucky became the 15th state in 1792, five commissioners from various counties were appointed, on 20 June 1792, to choose a location for the capital. They were John Allen and John Edwards (both from Bourbon County), Henry Lee (from Mason), Thomas Kennedy (from Madison), and Robert Todd (from Fayette). A number of communities competed for this honor, but Frankfort won. According to early histories, the offer of Andrew Holmes' log house as capitol for seven years, a number of town lots, £50 worth of locks and hinges, 10 boxes of glass, 1,500 pounds of nails, and $3,000 in gold helped the decision go to Frankfort.[16]

Frankfort had a United States post office by 1794, with Daniel Weisiger as postmaster. On 1 October 1794, Weisiger sent the first quarterly account to Washington.[17]

John Brown, a Virginia lawyer and statesman, built a home now called Liberty Hall in Frankfort in 1796. Before Kentucky statehood, he represented Virginia in the Continental Congress (1777−78) and the U.S. Congress (1789−91). While in Congress, he introduced the bill granting statehood to Kentucky. After statehood, he was elected by the state legislature as one of the state's U.S. Senators.[18]

In 1796, the Kentucky General Assembly appropriated funds to provide a house to accommodate the governor; it was completed two years later. The Old Governor's Mansion is claimed to be the oldest official executive residence still in use in the United States. In 1829, Gideon Shryock designed the Old Capitol, Kentucky's third, in Greek Revival style. It served Kentucky as its capitol from 1830 to 1910. The separate settlement known as South Frankfort was annexed by the city on 3 January 1850.[19]

The Argus of Western America was published in Frankfort from 1808 until 1830.[20]

During the American Civil War, the Union Army built fortifications overlooking Frankfort on what is now called Fort Hill. The Confederate Army also occupied Frankfort for a short time, starting on 3 September 1862, the only such time that Confederate forces took control of a Union capitol.[15]

The Clinton Street High School, a segregated public school for African American students in Frankfort operated from either 1882 or 1884 until 1928.[21][22]

20th-century

[edit]

On 3 February 1900, William Goebel was assassinated in Frankfort while walking to the capitol on the way to the Kentucky Legislature. Former Secretary of State Caleb Powers and several others were later found guilty of a conspiracy to murder Goebel, however all were later pardoned.[23]

The Mayo–Underwood School, the successor to the Clinton Street High School, was a public school for African American students in Frankfort and operated from 1929 until 1964.[21][22] The school was torn down as part of an urban renewal plan,[24] and to make way for the Capital Plaza.

The Capital Plaza was comprised the Capital Plaza Office Tower, the tallest building in the city, the Capital Plaza Hotel (formerly the Holiday Inn, Frankfort), and the Fountain Place Shoppes. The Capital Plaza Office Tower opened in 1972 and became a visual landmark for the center of the city. By the early 2000s, maintenance of the concrete structures had been neglected and the plaza had fallen into disrepair, with sections of the plaza closed to pedestrian activity out of concerns for safety.

Frankfort grew considerably with state government in the 1960s. A modern addition to the State Office Building was completed in 1967. The original building was completed in the 1930s on the location of the former Kentucky State Penitentiary. Some of the stone from the old prison was used for the walls surrounding the office building.[25]

21st-century

[edit]Although there was some rapid economic and population growth in the 1960s, both tapered off in the 1980s and have remained fairly stable since that time.[26]

In August 2008, state government officials recommended demolition of the Capital Plaza Office Tower and redevelopment of the area over a period of years. Ten years later, the demolition of the office tower was completed on Sunday, March 11, 2018,[27] and was televised by WKYT-TV on WKYT-DT2, as well as streamed live on Facebook. Demolition of the nearby convention center, which opened in 1972 and has hosted sporting events, concerts, and other local events, was completed in spring 2018.[27] State officials replaced the outdated office tower with a smaller building called the Mayo–Underwood Building (2019),[28][29] in order to create a more pedestrian-oriented scale at the complex, to encourage street activity.[30]

Frankfort is home to three distilleries including the Buffalo Trace Distillery (Kentucky Bourbon), Castle & Key Distillery (spirits), and Three Boys Farm Distillery (bourbon and whiskey).[31]

In 2018, thousands of teachers protested at the city in response to Senate Bill 151 having been passed on 29 March 2018.[32] The bill was shortly overturned on December 13, 2018, by the Kentucky Supreme Court as unconstitutional, which prevented the bill from going into effect on January 1, 2019.

Geography

[edit]

Frankfort is located in the (inner) Bluegrass region of Central Kentucky. The city is bisected by the Kentucky River, which makes an s-turn as it passes through the center of town. The river valley widens at this point, which creates four distinct parts of town. The valley within the city limits contains Downtown and South Frankfort districts, which lie opposite one another on the river. A small neighborhood with its own distinct identity, Bellepoint, is located on the west bank of the river to the north of Benson Creek, opposite the river from the "downtown" district. The suburban areas on either side of the valley are respectively referred to as the "West Side" and "East Side" (or "West Frankfort" and "East Frankfort").

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 14.6 square miles (37.8 km2), of which 14.3 square miles (37.0 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.78 km2) is water.

Frankfort does not have a commercial airport and travelers fly into Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, the closest; Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport near Covington or Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport in Louisville. Capital City Airport serves general and military aviation.

Climate

[edit]Frankfort has a humid subtropical climate with four distinct seasons. Winter is generally cool with some snowfall. Spring and fall are both mild and relatively warm, with ample precipitation and thunderstorm activity. Summers are hot and humid.

| Climate data for Frankfort Capital City Airport, Kentucky (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1996–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

80 (27) |

84 (29) |

87 (31) |

91 (33) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

99 (37) |

97 (36) |

84 (29) |

73 (23) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.0 (18.3) |

68.8 (20.4) |

76.0 (24.4) |

82.7 (28.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

92.1 (33.4) |

94.0 (34.4) |

93.7 (34.3) |

91.8 (33.2) |

84.0 (28.9) |

73.8 (23.2) |

66.5 (19.2) |

96.0 (35.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.1 (6.2) |

47.6 (8.7) |

57.2 (14.0) |

68.5 (20.3) |

76.7 (24.8) |

84.7 (29.3) |

87.6 (30.9) |

87.1 (30.6) |

81.1 (27.3) |

69.5 (20.8) |

56.7 (13.7) |

46.8 (8.2) |

67.2 (19.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.1 (1.2) |

37.8 (3.2) |

46.2 (7.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

65.5 (18.6) |

73.7 (23.2) |

77.2 (25.1) |

76.1 (24.5) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.6 (14.2) |

46.1 (7.8) |

38.1 (3.4) |

56.5 (13.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

35.3 (1.8) |

44.8 (7.1) |

54.4 (12.4) |

62.8 (17.1) |

66.8 (19.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

45.7 (7.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

45.8 (7.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 2.0 (−16.7) |

8.2 (−13.2) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

37.0 (2.8) |

48.7 (9.3) |

55.7 (13.2) |

53.5 (11.9) |

43.1 (6.2) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

10.2 (−12.1) |

0.0 (−17.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−21 (−29) |

−10 (−23) |

21 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

42 (6) |

50 (10) |

48 (9) |

35 (2) |

22 (−6) |

9 (−13) |

−3 (−19) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.27 (83) |

3.40 (86) |

4.72 (120) |

4.55 (116) |

5.10 (130) |

4.34 (110) |

4.69 (119) |

3.15 (80) |

3.35 (85) |

3.64 (92) |

3.36 (85) |

3.77 (96) |

47.34 (1,202) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.2 | 11.4 | 12.3 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 12.0 | 138.4 |

| Source: NOAA[33][34] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Downtown Frankfort, Kentucky (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1895–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

106 (41) |

111 (44) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

98 (37) |

84 (29) |

78 (26) |

111 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.5 (5.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

55.8 (13.2) |

66.5 (19.2) |

75.2 (24.0) |

83.6 (28.7) |

87.3 (30.7) |

86.7 (30.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

69.5 (20.8) |

57.3 (14.1) |

45.0 (7.2) |

66.2 (19.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.7 (−0.2) |

35.3 (1.8) |

43.5 (6.4) |

53.5 (11.9) |

62.7 (17.1) |

71.5 (21.9) |

75.5 (24.2) |

74.6 (23.7) |

67.5 (19.7) |

56.2 (13.4) |

45.6 (7.6) |

35.4 (1.9) |

54.4 (12.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

40.5 (4.7) |

50.1 (10.1) |

59.5 (15.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

62.5 (16.9) |

54.6 (12.6) |

43.0 (6.1) |

34.0 (1.1) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

42.6 (5.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−16 (−27) |

−3 (−19) |

16 (−9) |

27 (−3) |

36 (2) |

48 (9) |

41 (5) |

30 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

−1 (−18) |

−17 (−27) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.70 (94) |

3.07 (78) |

4.39 (112) |

3.74 (95) |

4.01 (102) |

4.06 (103) |

4.14 (105) |

3.45 (88) |

2.90 (74) |

2.53 (64) |

3.29 (84) |

3.49 (89) |

42.77 (1,086) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.4 (8.6) |

2.8 (7.1) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

1.6 (4.1) |

9.4 (24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 114 |

| Source 1: NOAA[35][36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Southeast Regional Climate Center (precipitation, snow 1895–2002)[37] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Newer information is available from the 2020 census report. (January 2022) |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 628 | — | |

| 1810 | 1,099 | 75.0% | |

| 1820 | 1,679 | 52.8% | |

| 1830 | 1,682 | 0.2% | |

| 1840 | 1,917 | 14.0% | |

| 1850 | 3,308 | 72.6% | |

| 1860 | 3,702 | 11.9% | |

| 1870 | 5,396 | 45.8% | |

| 1880 | 6,958 | 28.9% | |

| 1890 | 7,892 | 13.4% | |

| 1900 | 9,487 | 20.2% | |

| 1910 | 10,465 | 10.3% | |

| 1920 | 9,805 | −6.3% | |

| 1930 | 11,626 | 18.6% | |

| 1940 | 11,492 | −1.2% | |

| 1950 | 11,916 | 3.7% | |

| 1960 | 18,365 | 54.1% | |

| 1970 | 21,902 | 19.3% | |

| 1980 | 25,973 | 18.6% | |

| 1990 | 25,968 | 0.0% | |

| 2000 | 27,741 | 6.8% | |

| 2010 | 25,527 | −8.0% | |

| 2020 | 28,602 | 12.0% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 28,391 | [38] | −0.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39][failed verification] 2020[7] | |||

As of the 2020 Census,[40] there were 28,602 people, 12,434 households, and 6,053 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,783 per square mile (688/km2). There were 12,938 housing units at an average density of 885.1 per square mile (341.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.1% White or European American (74.1% non-Hispanic), 13.3% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.6% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 1.8% from other races, and 4.8% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 5.2% of the population.

There were 12,434 households, out of which 27.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32,6% were married couples living together, 16.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 45.7% were non-families. 38.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.12 and the average family size was 2.83.

The age distribution was 19.8% under 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 25.5% from 45 to 64, and 16.1% who were 65 or older. The median age was 36.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $50,211, and the median income for a family was $43,949. Full-time male workers had a median income of $37,445 versus $34,613 for females. The per capita income was $29,288. About 19.8% of families and 16.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.7% of those under age 18 and 7.5% of those age 65 or over.

Frankfort is the focal point of a micropolitan statistical area consisting of Frankfort and Franklin County as well as adjacent Lawrenceburg and Anderson County. The city is also classified in a combined statistical area with Lexington and Richmond to the east.

Frankfort's municipal population makes it the fourth least populous capital city in the United States.[41]

Parks and recreation

[edit]The city operates nine parks:[42]

- Capitol View—playing fields, nature trails, picnic areas

- Cove Spring—240 acres (97 hectares), nature trails, picnic areas, archery range

- Dolly Graham—basketball courts, picnic, community garden, playground

- East Frankfort—nature trails, dog park, picnic areas, playgrounds, volleyball court, 18-hole disc golf course.[43]

- Juniper Hill Park—124 acres (50.2 hectares), pool, golf course, play areas, picnic areas, war memorials

- Lakeview (operated jointly with Franklin County[44])—ball fields, golf course, horse show arena, skatepark

- Leslie Morris Park on Fort Hill—American Civil War battlefield, wilderness forest, forts, trails

- River View—picnic area along the Kentucky River, walking trail with historic cultural sites, amphitheatre, boat ramp, farmers market

- Todd Park—trail, picnic areas, community garden

Other recreation in the area:

- Walk/Bike Frankfort - Volunteer group to improve the city for pedestrians and cyclists.[45]

- Josephine Sculpture Park - Provides community arts education and creative experiences.[46]

- The Folkbike Re-Cyclery - Volunteer organization that restores and repairs used bicycles, and then gives them to riders who cannot afford to buy one.[47][48]

Education

[edit]Kentucky State University is located with the Frankfort city limits. KSU (also known as KYSU) is a public historically black university and an 1890 land-grant institution.[49]

Two public school districts serve the city,[50] with three public high schools within the city limits.[49]

Frankfort Independent School District serves the downtown neighborhoods including Downtown, South Frankfort, Bellepoint and Tanglewood. FIS operates The Early Learning Academy (a preschool), Second Street School (primary and middle grades), Frankfort High School, and Panther Transition Academy (a non-traditional high school program).[51]

Franklin County Public Schools serves the rest of the city and county, including seven elementary schools (Bridgeport, Collins Lane, Early Learning Village, Elkhorn, Hearn, Peaks Mill, Westridge), two middle schools (Bondurant, Elkhorn), and two high schools (Franklin County High School and Western Hills High School).[52]

There are several private schools in the area, including Capital Day School, Frankfort Christian Academy, and Good Shepherd Catholic School.

Frankfort has a lending library, Paul Sawyier Public Library, named in 1965 after the watercolor artist Paul Sawyier whose many paintings document the history of the area.[53][54][55]

Points of interest

[edit]

- Kentucky State Capitol building, built 1909

- Kentucky Governor's Mansion, residence of the Governor of Kentucky, built 1914

- Old State Capitol building, now a museum, built 1837

- Courthouse, built 1887

- Singing Bridge, a 125-year-old bridge that crosses the Kentucky River, built 1893

- Liberty Hall, historic house museum, built 1796

- Fort Hill, a hill overlooking downtown, American Civil War site, now a park

- Frankfort Cemetery, historic military monuments and final resting place of numerous statesmen and famous figures, established 1844

- Corner in Celebrities Historic District

- Buffalo Trace Distillery, built 1792

- Jesse R. Zeigler House (private), Kentucky's only Frank Lloyd Wright, built 1909

- Capital City Museum, a repository of the history of Frankfort and Franklin County[13]

- Leestown, Kentucky (historical site established in 1775, currently in the city of Frankfort)

Transportation

[edit]Frankfort Transit provides deviated fixed-route and demand-response transit service throughout the city.

U.S. Route 60 and U.S. Route 460 pass east–west through Frankfort. U.S. Route 127 and U.S. Route 421 pass north–south through Frankfort. Interstate 64 passes to the south of the city.

Capital City Airport, a public use airport, is one mile (1.5 kilometers) southwest of the central business district of Frankfort. The nearest airport with commercial flights is Blue Grass Airport, 22 miles (35 kilometers) southeast of Frankfort.

Frankfort Union Station was a medium scale hub passenger train station for north-central Kentucky. It served the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, the Frankfort and Cincinnati Railroad and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.[56] Until the mid-1950s, Union Station served Louisville-Ashland sections of the C&O's Sportsman. Until 1971, the C&O's George Washington stopped in Frankfort.[57][58]

Notable people

[edit]

- William Wirt Adams (1819−88), brigadier general in the Confederate Army[59]

- Thomas Carlin, seventh Governor of Illinois[60]

- Will Chase, actor and singer best known for Broadway musicals and ABC series Nashville

- Elijah Craig, Baptist preacher and early bourbon distiller, moved to Frankfort from Virginia in the 1780s

- Tim Farmer, outdoorsman and television presenter; host of Kentucky Afield

- William Goebel, 34th Governor of Kentucky

- John Marshall Harlan, U.S. Supreme Court justice

- Elizabeth Ann Hulette, professional wrestling manager

- Grover Land (1884−1958), professional baseball player

- Crit Luallen, lieutenant governor of Kentucky (2014 - 2015), Kentucky State Auditor (2004 - 2012)

- Archer Prewitt, musician and cartoonist

- J. T. Riddle, professional baseball player for the Minnesota Twins

- Green Pinckney Russell (1861/1863–1939), American school administrator, college president, and teacher[61]

- Paul Sawyier (1865−1917), Kentucky Impressionist artist

- Arthur St. Clair, 1700s soldier and politician, after which St Clair Street is named

- Landon Addison Thomas (1799−1889), state legislator

- George Graham Vest (1830−1904), U.S. Senator from Missouri, best known for popularizing the notion that a dog is a man's best friend[62]

- James Wilkinson, who named Mero St. after his paymaster, Louisiana Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró.[63]

- Anne Elizabeth Wilson (1901–1946), writer, poet, editor

- George C. Wolfe (1954−), Broadway producer, playwright, and film director

- Logan Woodside, NFL Quarterback

- Wan'Dale Robinson, professional football player for the New York Giants

Sister cities

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

The floral clock near the Capitol building

-

Downtown Frankfort

-

Downtown Frankfort at night

-

Grave site of pioneer Daniel Boone and his wife at Frankfort Cemetery

-

Jackson Hall of Kentucky State University

-

Whitaker Bank building

References

[edit]- ^ "Mayor Layne Wilkerson". City of Frankfort, Kentucky. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Frankfort, Kentucky

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Summary and Reference Guide to House Bill 331 City Classification Reform" (PDF). Kentucky League of Cities. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts: Frankfort city, Kentucky". census.gov. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c "City History". Official website. City of Frankfort, Kentucky. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Kentucky Historical Marker 1774" Archived August 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Kentucky Historical Society Website

- ^ a b c d "Geography | Frankfort, KY". www.frankfort.ky.gov. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Station: Frankfort Lock 4, KY". U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1981-2010). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Monthly Highest Max Temperature and Monthly Lowest Min Temperature for Frankfort Downtown, KY". Applied Climate Information System. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ a b "Capital City Museum | Frankfort KY". www.capitalcitymuseum.com. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Economy | Frankfort, KY". www.frankfort.ky.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "City History". Official website. City of Frankfort, Kentucky. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Kentucky Historical Marker 1774" Archived August 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Kentucky Historical Society Website

- ^ Rennick, Robert M. (1993) Kentucky's Bluegrass: A Survey of the Post Offices, pp. 91 & 99. Lake Grove, Oregon: The Depot, ISBN 0-943645-31-X. Post Office Department records were destroyed by a fire in 1836.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress - Retro Search". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ Commonwealth of Kentucky. Office of the Secretary of State. Land Office. "Frankfort, Kentucky". Accessed July 25, 2013.

- ^ "How Politicians Bought the 19th Century Media". Steve Inskeep: NPR Host and Author. May 4, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "African American Schools in Frankfort and Franklin County, KY". Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, University of Kentucky Libraries, University of Kentucky. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Boyd, Douglas (August 1, 2011). Crawfish Bottom: Recovering a Lost Kentucky Community. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-8131-3409-3.

- ^ Egerton, John (April 10, 1983). Generations: An American Family. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813127831 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Capital Plaza Authority Asks Mayo–Underwood School Site". The Lexington Herald. August 31, 1966. p. 13. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Knight's Penny Magazine". Charles Knight & Company. April 10, 1834 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jochim, Mark Joseph (May 31, 2018). "Kentucky & Tennessee Statehood". A Stamp A Day. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Miller, Alfred (January 14, 2018). "Dates set for Frankfort Convention Center, Capital Plaza Tower demolition". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ "State office building named after historic Frankfort African American school". The State Journal. August 13, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "New state office building in downtown Frankfort officially named". ABC 36 News. August 13, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ Redevelopment Plan",[dead link] Kentucky

- ^ "Home of the Distilleries of Bourbon Country". Bourbon Country.

- ^ Blackford, Linda. "See the best video, photos as Kentucky teachers pack Frankfort, protest in the Capitol". kentucky. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Frankfort Capital City AP, KY". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Frankfort Lock 4, KY". U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1981-2010). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Monthly Highest Max Temperature and Monthly Lowest Min Temperature for Frankfort Downtown, KY". Applied Climate Information System. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "General Climate Summary tables". Southeast Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "The 10 Least Populated State Capitals". WorldAtlas. November 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ "Parks". www.frankfortparksandrec.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Lawrenceburg Disc Golf Association - Lawrenceburg (KY) Disc Golf Association". Lawrenceburg Disc Golf Association. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "Parks & Recreation | Franklin County".

- ^ "Walk/Bike Frankfort". Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ "Josephine Sculpture Park". Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "The Folkbike Re-Cyclery - Join The Revolution - Frankfort, KY". folkbikerecyclery.org. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Staff (May 1, 2013). "How to Celebrate Kentucky Derby 2013 in Central Kentucky". Ace. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "Education | Frankfort, KY". www.frankfort.ky.gov.

- ^ "2020 census - school district reference map: Franklin County, KY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 11, 2022. - Text list - For more detailed boundaries of the independent school districts see: "Appendix B: Maps Of Independent School Districts In Operation In FY 2014-FY 2015 Using 2005 Tax District Boundaries – Frankfort ISD" (PDF). Research Report No. 415 – Kentucky's Independent School Districts: A Primer. Frankfort, KY: Office of Education Accountability, Legislative Research Commission. September 15, 2015. p. 110 (PDF p. 124/174).

- ^ "Frankfort Independent Schools". www.frankfort.k12.ky.us. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ "Franklin County Schools". www.franklin.kyschools.us.

- ^ "Kentucky Public Library Directory". Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ Roe, Amy. "Paul Sawyier Library". ExploreKYHistory. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Paul Sawyier Art Exhibit". pspl.org. September 8, 2018. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ Official Guide of the Railways, June 1921, p. 1294

- ^ Chesapeake & Ohio timetable, June 1948 ,Tables 5, 6, 13, 14

- ^ Louisville & Nashville timetable, December 1948, Tables 10, 20

- ^ Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607−1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ "Illinois Governor Thomas Carlin". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Mather, Frank Lincoln (1915). Who's Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent; Vol. 1. p. 236.

- ^ "George Graham Vest: Tribute to the Dog". The History Place. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Robert Brammer (April 21, 2020). "General James Wilkinson, the Spanish Spy Who was a Senior Officer in the U.S. Army During Four Presidential Administrations". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

Frankfort, the capital of Kentucky, where Wilkinson laid out the grid for many of the early streets. Wilkinson brazenly named one of those streets for a Spanish governor who was paying him, Mero Street (the correct spelling of the governor's name is Miro)

- ^ "New sister city official | The State Journal". www.state-journal.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Official site

- Frankfort Information page from Kentucky Secretary of State Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. IX (9th ed.). 1879. p. 704.