Francis Bacon: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 209.106.212.253 to version by Danilloclm. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (885656) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

===Early life=== |

===Early life=== |

||

[[Image:18-year old Francis Bacon.jpg|thumb|right|The 18-year old Francis Bacon. National Portrait Gallery, London]] |

[[Image:18-year old Francis Bacon.jpg|thumb|right|The 18-year old Francis Bacon is in fact a Homosexual. National Portrait Gallery, London]] |

||

Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at [[York House, Strand|York House]] near the [[Strand, London|Strand]] in London, the son of [[Nicholas Bacon (courtier)|Sir Nicholas Bacon]] by his second wife [[Anne Bacon|Anne (Cooke) Bacon]], the daughter of noted [[Renaissance humanism|humanist]] [[Anthony Cooke]]. His mother's sister was married to [[William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley]], making Burghley Francis Bacon's uncle. |

Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at [[York House, Strand|York House]] near the [[Strand, London|Strand]] in London, the son of [[Nicholas Bacon (courtier)|Sir Nicholas Bacon]] by his second wife [[Anne Bacon|Anne (Cooke) Bacon]], the daughter of noted [[Renaissance humanism|humanist]] [[Anthony Cooke]]. His mother's sister was married to [[William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley]], making Burghley Francis Bacon's uncle. |

||

Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health (which plagued him throughout his life), receiving tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning towards [[Puritan]]ism. He entered [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], on 5 April 1573 at the age of twelve,<ref>{{Venn|id=BCN573F|name=Bacon, Francis}}</ref> living for three years there together with his older brother [[Anthony Bacon (1558–1601)|Anthony]] under the personal tutelage of Dr [[John Whitgift]], future [[Archbishop of Canterbury]]. Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. He was also educated at the [[University of Poitiers]]. It was at Cambridge that he first met [[Queen Elizabeth I|Queen Elizabeth]], who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him "the young Lord Keeper".<ref>{{cite book | last = Collins | first = Arthur | title = The English Baronetage: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the English Baronets, Now Existing: Their Descents, Marriages, and Issues; Memorable Actions, Both in War, and Peace; Religious and Charitable Donations; Deaths, Places of Burial and Monumental Inscriptions [sic] | publisher=Printed for Tho. Wotton at the Three Daggers and Queen's Head | year = 1741 | page = 5}}</ref> |

Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health (which plagued him throughout his life), receiving tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning towards [[Puritan]]ism. He entered [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], on 5 April 1573 at the age of twelve,<ref>{{Venn|id=BCN573F|name=Bacon, Francis}}</ref> living for three years there together with his older brother [[Anthony Bacon (1558–1601)|Anthony]] under the personal tutelage of Dr [[John Whitgift]], future [[Archbishop of Canterbury]]. Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. He was also educated at the [[University of Poitiers]]. It was at Cambridge that he first met [[Queen Elizabeth I|Queen Elizabeth]], who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him "the young Lord Keeper".<ref>{{cite book | last = Collins | first = Arthur | title = The English Baronetage: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the English Baronets, Now Existing: Their Descents, Marriages, and Issues; Memorable Actions, Both in War, and Peace; Religious and Charitable Donations; Deaths, Places of Burial and Monumental Inscriptions [sic] | publisher=Printed for Tho. Wotton at the Three Daggers and Queen's Head | year = 1741 | page = 5}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:26, 14 February 2012

Francis Bacon | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Francis Bacon, by John Vanderbank (ca. 1731), after a portrait by an unknown artist (circa 1618). | |

| Born | 22 January 1561 Strand, London, England |

| Died | 9 April 1626 (aged 65) Highgate, London, England |

| Alma mater | Cambridge University |

| Era | English Renaissance , The Scientific Revolution |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Renaissance Philosophy , Empiricism |

| Signature | |

| |

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban(s),[1] KC (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Although his political career ended in disgrace, he remained extremely influential through his works, especially as philosophical advocate and practitioner of the scientific method during the scientific revolution.

Bacon has been called the creator of empiricism.[2] His works established and popularised inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the Baconian method, or simply the scientific method. His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology today. Since this profession was rasher than most others, his dedication probably led to his death, bringing him into a rare historical group of scientists who were killed by their own experiments.

Bacon was knighted in 1603, and created both the Baron Verulam in 1618, and the Viscount St Alban in 1621;[3] as he died without heirs both peerages became extinct upon his death. He famously died of pneumonia contracted while studying the effects of freezing on the preservation of meat.

Biography

Early life

Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at York House near the Strand in London, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon by his second wife Anne (Cooke) Bacon, the daughter of noted humanist Anthony Cooke. His mother's sister was married to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, making Burghley Francis Bacon's uncle. Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health (which plagued him throughout his life), receiving tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning towards Puritanism. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge, on 5 April 1573 at the age of twelve,[4] living for three years there together with his older brother Anthony under the personal tutelage of Dr John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. He was also educated at the University of Poitiers. It was at Cambridge that he first met Queen Elizabeth, who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him "the young Lord Keeper".[5]

His studies brought him to the belief that the methods and results of science as then practised were erroneous. His reverence for Aristotle conflicted with his loathing of Aristotelian philosophy, which seemed to him barren, disputatious, and wrong in its objectives.

On 27 June 1576, he and Anthony entered de societate magistrorum at Gray's Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris, while Anthony continued his studies at home. The state of government and society in France under Henry III afforded him valuable political instruction. For the next three years he visited Blois, Poitiers, Tours, Italy, and Spain. During his travels, Bacon studied language, statecraft, and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks. On at least one occasion he delivered diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, and Leicester, as well as for the queen.

The sudden death of his father in February 1579 prompted Bacon to return to England. Sir Nicholas had laid up a considerable sum of money to purchase an estate for his youngest son, but he died before doing so, and Francis was left with only a fifth of that money. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. To support himself, he took up his residence in law at Gray's Inn in 1579.

Parliamentarian

Bacon's threefold goals were to uncover truth, to serve his country, and to serve his church. He sought to further these ends by seeking a prestigious post. In 1580, through his uncle, Lord Burghley, he applied for a post at court, which might enable him to pursue a life of learning. His application failed. For two years he worked quietly at Gray's Inn, until he was admitted as an outer barrister in 1582.

His parliamentary career began when he was elected MP for Bossiney, Devon in a 1581 by-election. In 1584, he took his seat in parliament for Melcombe in Dorset, and subsequently for Taunton (1586). At this time, he began to write on the condition of parties in the church, as well as on the topic of philosophical reform in the lost tract, Temporis Partus Maximus. Yet, he failed to gain a position he thought would lead him to success. He showed signs of sympathy to Puritanism, attending the sermons of the Puritan chaplain of Gray's Inn and accompanying his mother to the Temple chapel to hear Walter Travers. This led to the publication of his earliest surviving tract, which criticised the English church's suppression of the Puritan clergy. In the Parliament of 1586, he openly urged execution for Mary, Queen of Scots.

About this time, he again approached his powerful uncle for help; this move was followed by his rapid progress at the bar. He became Bencher in 1586, and he was elected a reader in 1587, delivering his first set of lectures in Lent the following year. In 1589, he received the valuable appointment of reversion to the Clerkship of the Star Chamber, although he did not formally take office until 1608 – a post which was worth £16,000 a year.[6]

In 1588 he was returned as MP for Liverpool and then for Middlesex in 1593. He later sat three times for Ipswich (1597, 1601, 1604) and once for Cambridge University (1614).[7]

He became known as a liberal-minded reformer, eager to amend and simplify the law. He opposed feudal privileges and dictatorial powers, though a friend of the crown. He was against religion persecution. He struck at the House of Lords in their usurpation of the Money Bills. He advocated for the union of England and Scotland, thus being one of the influences behind the consolidation of the United Kingdom; and also advocated, later on, for the integration of Ireland into the Union. These, he believed, would bring greater peace and strength to these countries. [8] [9]

Attorney General

Bacon soon became acquainted with Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, Queen Elizabeth's favourite. By 1591, he acted as the earl's confidential adviser.

In 1592, he was commissioned to write a tract in response to the Jesuit Robert Parson's anti-government polemic, which he entitled Certain observations made upon a libel, identifying England with the ideals of democratic Athens against the belligerence of Spain.

Bacon took his third parliamentary seat for Middlesex when in February 1593 Elizabeth summoned Parliament to investigate a Roman Catholic plot against her. Bacon's opposition to a bill that would levy triple subsidies in half the usual time offended many people.[clarification needed] Opponents accused him of seeking popularity. For a time, the royal court excluded him.

When the Attorney-Generalship fell vacant in 1594, Lord Essex's influence was not enough to secure Bacon that office. Likewise, Bacon failed to secure the lesser office of Solicitor-General in 1595.[6] To console him for these disappointments, Essex presented him with a property at Twickenham, which he sold subsequently for £1,800.

In 1596, Bacon became Queen's Counsel, but missed the appointment of Master of the Rolls. During the next few years, his financial situation remained bad. His friends could find no public office for him, and a scheme for retrieving his position by a marriage with the wealthy and young widow Lady Elizabeth Hatton failed after she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to a wealthier man. In 1598 Bacon was arrested for debt. Afterwards however, his standing in the Queen's eyes improved. Gradually, Bacon earned the standing of one of the learned counsels, though he had no commission or warrant and received no salary. His relationship with the Queen further improved when he severed ties with Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, a shrewd move because Essex was executed for treason in 1601.

With others, Bacon was appointed to investigate the charges against Essex, his former friend and benefactor. A number of Essex's followers confessed that Essex had planned a rebellion against the Queen.[10] Bacon was subsequently a part of the legal team headed by Attorney General Sir Edward Coke at Essex's treason trial.[10] After the execution, the Queen ordered Bacon to write the official government account of the trial, which was later published as A DECLARATION of the Practices and Treasons attempted and committed by Robert late Earle of Essex and his Complices, against her Majestie and her Kingdoms ... after Bacon's first draft was heavily edited by the Queen and her ministers.[11]

According to his personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, as a judge Bacon was always tender-hearted, "looking upon the examples with the eye of severity, but upon the person with the eye of pity and compassion". And also that "he was free from malice", "no revenger of injuries", and "no defamer of any man". [12]

James I comes to the throne

The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. In another shrewd move, Bacon wrote his Apologie in defence of his proceedings in the case of Essex, as Essex had favoured James to succeed to the throne.

The following year, during the course of the uneventful first parliament session, Bacon married Alice Barnham. In June 1607 he was at last rewarded with the office of Solicitor-General.[6] The following year, he began working as the Clerkship of the Star Chamber. In spite of a generous income, old debts still couldn't be paid. He sought further promotion and wealth by supporting King James and his arbitrary policies.

In 1610 the fourth session of James' first parliament met. Despite Bacon's advice to him, James and the Commons found themselves at odds over royal prerogatives and the king's embarrassing extravagance. The House was finally dissolved in February 1611. Throughout this period Bacon managed to stay in the favour of the king while retaining the confidence of the Commons.

In 1613, Bacon was finally appointed attorney general, after advising the king to shuffle judicial appointments. As attorney general, Bacon prosecuted Somerset in 1616. The so-called "Prince's Parliament" of April 1614 objected to Bacon's presence in the seat for Cambridge and to the various royal plans which Bacon had supported. Although he was allowed to stay, parliament passed a law that forbade the attorney-general to sit in parliament. His influence over the king had evidently inspired resentment or apprehension in many of his peers. Bacon, however, continued to receive the King's favour, which led to his appointment in March 1617 as the temporary Regent of England (for a period of a month), and in 1618 as Lord Chancellor. On 12 July 1618 the king created Bacon Baron Verulam, of Verulam, in the Peerage of England. As a new peer he then styled himself as "Francis, Lord Verulam".[6]

Bacon continued to use his influence with the king to mediate between the throne and Parliament and in this capacity he was further elevated in the same peerage, as Viscount St Alban, on 27 January 1621.[13]

Lord Chancellor and public disgrace

Bacon's public career ended in disgrace in 1621. After he fell into debt, a Parliamentary Committee on the administration of the law charged him with twenty-three separate counts of corruption. To the lords, who sent a committee to enquire whether a confession was really his, he replied, "My lords, it is my act, my hand, and my heart; I beseech your lordships to be merciful to a broken reed." He was sentenced to a fine of £40,000 and committed to the Tower of London during the king's pleasure; the imprisonment lasted only a few days and the fine was remitted by the king.[14] More seriously, parliament declared Bacon incapable of holding future office or sitting in parliament. He narrowly escaped undergoing degradation, which would have stripped him of his titles of nobility. Subsequently the disgraced viscount devoted himself to study and writing.

There seems little doubt that Bacon had accepted gifts from litigants, but this was an accepted custom of the time and not necessarily evidence of deeply corrupt behaviour.[15] While acknowledging that his conduct had been lax, he countered that he had never allowed gifts to influence his judgement and, indeed, he had on occasion given a verdict against those who had paid him. The true reason for his acknowledgement of guilt is the subject of debate, but it may have been prompted by his poor state of health, or by a view that through his fame and the greatness of his office he would be spared harsh punishment. He may even have been blackmailed, with a threat to charge him with sodomy, into confession.[15][16]

The British jurist Basil Montagu wrote in Bacon's defense, concerning the episode of his public disgrace:

Bacon has been accused of servility, of dissimulation, of various base motives, and their filthy brood of base actions, all unworthy of his high birth, and incompatible with his great wisdom, and the estimation in which he was held by the noblest spirits of the age. It is true that there were men in his own time, and will be men in all times, who are better pleased to count spots in the sun than to rejoice in its glorious brightness. Such men have openly libelled him, like Dewes and Weldon, whose falsehoods were detected as soon as uttered, or have fastened upon certain ceremonious compliments and dedications, the fashion of his day, as a sample of his servility, passing over his noble letters to the Queen, his lofty contempt for the Lord Keeper Puckering, his open dealing with Sir Robert Cecil, and with others, who, powerful when he was nothing, might have blighted his opening fortunes for ever, forgetting his advocacy of the rights of the people in the face of the court, and the true and honest counsels, always given by him, in times of great difficulty, both to Elizabeth and her successor. When was a "base sycophant" loved and honoured by piety such as that of Herbert, Tennison, and Rawley, by noble spirits like Hobbes, Ben Jonson, and Selden, or followed to the grave, and beyond it, with devoted affection such as that of Sir Thomas Meautys.

[17]

Personal life

When he was 36, Bacon engaged in the courtship of Elizabeth Hatton, a young widow of 20. Reportedly, she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to a wealthier man—Edward Coke. Years later, Bacon still wrote of his regret that the marriage to Hatton had not taken place.[18]

At the age of forty-five, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the fourteen-year-old daughter of a well-connected London alderman and MP. Bacon wrote two sonnets proclaiming his love for Alice. The first was written during his courtship and the second on his wedding day, 10 May 1606. When Bacon was appointed Lord Chancellor, "by special Warrant of the King", Lady Bacon was given precedence over all other Court ladies.

Reports of increasing friction in his marriage to Alice appeared, with speculation that some of this may have been due to financial resources not being as readily available to her as she was accustomed to having in the past. Alice was reportedly interested in fame and fortune, and when reserves of money were no longer available, there were complaints about where all the money was going. Alice Chambers Bunten wrote in her Life of Alice Barnham[19] that, upon their descent into debt, she actually went on trips to ask for financial favours and assistance from their circle of friends. Bacon disinherited her upon discovering her secret romantic relationship with John Underhill. He rewrote his will, which had previously been very generous to her (leaving her lands, goods, and income), revoking it all.

Bacon's personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, however, wrote in his biography of Bacon that his inter-marriage with Alice Barnham was one of "much conjugal love and respect", mentioning a robe of honour that he gave to her, and which "she wore unto her dying day, being twenty years and more after his death". [12]

The well-connected antiquary John Aubrey noted in his Brief Lives concerning Bacon, "He was a Pederast. His Ganimeds and Favourites tooke Bribes",[20] biographers continue to debate about Bacon's sexual inclinations and the precise nature of his personal relationships.[21] Several authors[22][23] believe that despite his marriage Bacon was primarily attracted to the same sex. Professor Forker[24] for example has explored the "historically documentable sexual preferences" of both King James and Bacon – and concluded they were all oriented to "masculine love", a contemporary term that "seems to have been used exclusively to refer to the sexual preference of men for members of their own gender."[25] The Jacobean antiquarian, Sir Simonds D'Ewes implied there had been a question of bringing him to trial for buggery.[26]

This conclusion has been disputed by others,[10][27][28] [29][30] who points out to lack of consistent evidence, and consider the sources to be more open to interpretation. In his "New Atlantis", Bacon describes his utopian island as being "the chastest nation under heaven", in which there was no prostitution or adultery, and further saying that "as for masculine love, they have no touch of it".[31]

Death

On 9 April 1626 Bacon died of pneumonia while at Arundel mansion at Highgate outside London. An influential account of the circumstances of his death was given by John Aubrey's Brief Lives. Aubrey has been criticised for his evident credulousness in this and other works; on the other hand, he knew Thomas Hobbes, Bacon's fellow-philosopher and friend. Aubrey's vivid account, which portrays Bacon as a martyr to experimental scientific method, had him journeying to Highgate through the snow with the King's physician when he is suddenly inspired by the possibility of using the snow to preserve meat: "They were resolved they would try the experiment presently. They alighted out of the coach and went into a poor woman's house at the bottom of Highgate hill, and bought a fowl, and made the woman exenterate it".

After stuffing the fowl with snow, Bacon contracted a fatal case of pneumonia. Some people, including Aubrey, consider these two contiguous, possibly coincidental events as related and causative of his death: "The Snow so chilled him that he immediately fell so extremely ill, that he could not return to his Lodging ... but went to the Earle of Arundel's house at Highgate, where they put him into ... a damp bed that had not been layn-in ... which gave him such a cold that in 2 or 3 days as I remember Mr Hobbes told me, he died of Suffocation."

Being unwittingly on his deathbed, the philosopher wrote his last letter to his absent host and friend Lord Arundel:

My very good Lord,—I was likely to have had the fortune of Caius Plinius the elder, who lost his life by trying an experiment about the burning of Mount Vesuvius; for I was also desirous to try an experiment or two touching the conservation and induration of bodies. As for the experiment itself, it succeeded excellently well; but in the journey between London and Highgate, I was taken with such a fit of casting as I know not whether it were the Stone, or some surfeit or cold, or indeed a touch of them all three. But when I came to your Lordship's House, I was not able to go back, and therefore was forced to take up my lodging here, where your housekeeper is very careful and diligent about me, which I assure myself your Lordship will not only pardon towards him, but think the better of him for it. For indeed your Lordship's House was happy to me, and I kiss your noble hands for the welcome which I am sure you give me to it. I know how unfit it is for me to write with any other hand than mine own, but by my troth my fingers are so disjointed with sickness that I cannot steadily hold a pen."[32]

Another account appears in a biography by William Rawley, Bacon's personal secretary and chaplain:

He died on the ninth day of April in the year 1626, in the early morning of the day then celebrated for our Saviour's resurrection, in the sixty-sixth year of his age, at the Earl of Arundel's house in Highgate, near London, to which place he casually repaired about a week before; God so ordaining that he should die there of a gentle fever, accidentally accompanied with a great cold, whereby the defluxion of rheum fell so plentifully upon his breast, that he died by suffocation.[33]

At the news of his death, over thirty great minds collected together their eulogies of him, which was then later published in Latin.[34]

He left personal assets of about £7,000 and lands that realised £6,000 when sold.[35] His debts amounted to more than £23,000, equivalent to more than £3m at current value.[35][36]

Philosophy and works

Francis Bacon is considered the father of modern science. He proposed, at his time, a big reformation of all process of knowledge for the advancement of learning divine and human. His called it Instauratio Magna (The Great Instauration). Bacon planned his Great Instauration in imitation of the Divine Work—the Work of the Six Days of Creation, as defined in the Bible, leading to the Seventh Day of Rest or Sabbath in which Adam's dominion over creation would be restored,[37] thus dividing the great reformation in six parts:

1. Partitions of the Sciences (De Augmentis Scientiarum)

2. New Method (Novum Organum)

3. Natural History (Historia Naturalis)

4. Ladder of the Intellect (Scala Intellectus)

5. Anticipations of the 2nd Philosophy (Anticipationes Philosophiæ Secunda)

6. The Second Philosophy or Active Science (Philosophia Secunda aut Scientia Activæ)

For Bacon, this reformation would lead to a great advancement in science and a progeny of new inventions that would relief mankind's miseries and needs.

In Novum Organum (the second part of the Instauration) he stated his view that the restoration of science was part of the "partial returning of mankind to the state it lived before the fall", restoring its dominion over creation, while religion and faith would partially restore mankind’s original state of innocency and purity.[38]

In the book "The Great Instauration", he also gave some admonitions regarding the ends and purposes of science, from which much of his philosophy can be deduced. He said that men should confine the sense within the limits of duty in respect to things divine, while not falling in the opposite error which would be to think that inquisition of nature is forbidden by divine law. Another admonition was concerning the ends of science: that mankind should seek knowledge not for pleasure, contention, superiority over others, profit, fame, or power; but for the benefit and use of life, and that they perfect and govern it in charity. [39]

He also wrote books proposing reformations of the law, as well as books on moral, religious and civil meditations.

Regarding faith, in De augmentis, he wrote that "the more discordant, therefore, and incredible, the divine mystery is, the more honour is shown to God in believing it, and the nobler is the victory of faith." He wrote in "The Essays: Of Atheism" that "a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion." Meanwhile in the very next essay called: "Of Superstition" Bacon remarks- "It were better to have no opinion of God at all, than such an opinion as is unworthy of him. For the one is unbelief, the other is contumely; and certainly superstition is the reproach of the Deity. [...] Superstition hath been the confusion of many states, and bringeth in a new primum mobile, that ravisheth all the spheres of government". [40]

Yet even more than this, Bacon's views of God are in accordance with popular Christian theology, as he writes that “They that deny a God destroy man's nobility; for certainly man is of kin to the beasts in his body; and, if he be not of kin to God by his spirit, he is a base and ignoble creature.”[41]

He considered science (natural philosophy) as a remedy against superstition, and therefore a "most faithful attendant" of religion, considering religion as the revelation of God's Will and science as the contemplation of God's Power.

Nevertheless, Bacon contrasted the new approach of the development of science with that of the Middle Ages:

"Men have sought to make a world from their own conception and to draw from their own minds all the material which they employed, but if, instead of doing so, they had consulted experience and observation, they would have the facts and not opinions to reason about, and might have ultimately arrived at the knowledge of the laws which govern the material world."

And spoke of the advancement of science in modern world as the fulfillment of a prophecy made in the Book of Daniel that said: "But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased". (See "Of the Interpretation of Nature").

According to author Nieves Mathews, the promoters of the French Reformation misrepresented Bacon by deliberately mistranslating and editing his writings to suit their anti-religious and materialistic concepts, which action would have carried a highly influential effect. [10].

Since Bacon's ideal was widespread revolution of the common method of scientific inquiry, there had to be some way by which his method could become widespread. His solution was to lobby the state to make natural philosophy a matter of greater importance – not only to fund it, but also to regulate it. While in office under Queen Elizabeth, he even advocated for the employment of a Minister for Science and Technology; a position which was never realised. Later under King James, Bacon wrote in The Advancement of Learning: "The King should take order for the collecting and perfecting of a Natural and Experimental History, true and severe (unencumbered with literature and book-learning), such as philosophy may be built upon, so that philosophy and the sciences may no longer float in air, but rest on the solid foundation of experience of every kind."[42]

While Bacon was a strong advocate for state involvement in scientific inquiry, he also felt that his general method should be applied directly to the functioning of the state as well. For Bacon, matters of policy were inseparable from philosophy and science. Bacon recognised the repetitive nature of history, and sought to correct it by making the future direction of government more rational. In order to make future civil history more linear and achieve real progress, he felt that methods of the past and experiences of the present should be examined together in order to determine the best ways by which to go about civil discourse. Bacon began one particular address to the house of Commons with a reference to the book of Jeremiah: "Stand in the ancient ways, but look also into present experience in order to see whether in the light of this experience ancient ways are right. If they are found to be so, walk in them." In short, he wanted his method of progress building on progress in natural philosophy to be integrated into England's political theory.[43]

Novum Organum

The Novum Organum is a philosophical work by Francis Bacon published in 1620. The title is a reference to Aristotle's work Organon, which was his treatise on logic and syllogism, and is the second part of his Instauration.

The book is divided in two parts, the first part being called "On the Interpretation of Nature and the Empire of Man", and the second "On the Interpretation of Nature, or the Reign of Man".

Bacon starts the work saying that man is "the minister and interpreter of nature", that "knowledge and human power are synonymous", that "effects are produced by the means of instruments and helps", and that "man while operating can only apply or withdraw natural bodies; nature internally performs the rest", and later that "nature can only be commanded by obeying her".[38] Here is an abstract of the philosophy of this work, that by the knowledge of nature and the using of instruments, man can govern or direct the natural work of nature to produce definite results. Therefore, that man, by seeking knowledge of nature, can reach power over it - and thus reestablish the "Empire of Man over creation", which had been lost by the Fall together with man's original purity. In this way, he believed, would mankind be raised above conditions of helplessness, poverty and misery, while coming into a condition of peace, prosperity and security.[44]

Bacon, taking into consideration the possibility of mankind misusing its power over nature gained by science, expressed his opinion that there was no need to fear it, for once mankind restored this power, that was “assigned to them by the gift of God”, it would be correctly governed by "right reason and true religion".[45] The moral aspects of the use of this power, and the way mankind should exercise it, however, are more explored in other works rather than the Novum Organum, such as in Valerius Terminus.

For this purpose of obtaining knowledge of and power over nature, Bacon outlined in this work a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism, developing his scientific method, consisting of procedures for isolating the formal cause of a phenomenon (heat, for example) through eliminative induction. For him, the philosopher should proceed through inductive reasoning from fact to axiom to physical law. Before beginning this induction, though, the enquirer must free his or her mind from certain false notions or tendencies which distort the truth. These are called "Idols" (idola),[46] and are of four kinds:

- "Idols of the Tribe" (idola tribus), which are common to the race;

- "Idols of the Den" (idola specus), which are peculiar to the individual;

- "Idols of the Marketplace" (idola fori), coming from the misuse of language; and

- "Idols of the Theatre" (idola theatri), which result from an abuse of authority.

About which, he stated:

If we have any humility towards the Creator; if we have any reverence or esteem of his works; if we have any charity towards men, or any desire of relieving their miseries and necessities; if we have any love for natural truths; any aversion to darkness, any desire of purifying the understanding, we must destroy these idols, which have led experience captive, and childishly triumphed over the works of God; and now at length condescend, with due submission and veneration, to approach and peruse the volume of the creation; dwell some time upon it, and bringing to the work a mind well purged of opinions, idols, and false notions, converse familiarly therein.[47]

Bacon considered that it is of greatest importance to science not to keep doing intellectual discussions or seeking merely contemplative aims in science, but that it should work for the bettering of mankind’s life by bringing forth new inventions, having even stated that "inventions are also, as it were, new creations and imitations of divine works" [38]. He cites examples from the ancient world, saying that in Ancient Egypt the inventors were reputed among the gods, and in a higher position than the heroes of the political sphere, such as legislators, liberators and the like. He explores the far-reaching and world-changing character of inventions, such as in the stretch:

"Printing, gunpowder and the compass: These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation; whence have followed innumerable changes, in so much that no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries."[38]

He also took into consideration what were the mistakes in the existing natural philosophies of the time and that required correction, pointing out three sources of error and three species of false philosophy: the sophistical, the empirical and the superstitious.

The sophistical school, according to Bacon, corrupted natural philosophy by their logic. This is school was criticized by Bacon for "determining the question according to their will, and just then resorts to experience, bending her into conformity".

Concerning the empirical school, Bacon said that it gives birth to dogmas more deformed and monstrous than the Sophistical or Rational School, and that it based itself in the narrowness and darkness of a few experiments.

For the superstitious school, he believed it to provoke great harm, for it consisted in a dangerous mixture of superstition with theology. He mentions as examples some systems of philosophy from Ancient Greece, and some (then) contemporary examples in which scholars would in levity take the Bible as a system of natural philosophy, which he considered to be an improper relationship between science and religion, stating that from "this unwholesome mixture of things human and divine there arises not only a fantastic philosophy but also an heretical religion". About which Professor Benjamin Farrington stated: "while it is a fact that he laboured to distinguish the realms of faith and knowledge, it is equally true that he thought one without the other useless".[48]

A common mistake, however, is to consider Bacon an empiricist. For, although he exhorted men to reject as idols all pre-conceived notions and lay themselves alongside of nature by observation and experiment, so as gradually to ascend from facts to their laws, nevertheless he was far from regarding sensory experience as the whole origin of knowledge, and in truth had a double theory, that, while sense and experience are the sources of our knowledge of the natural world, faith and inspiration are the sources of our knowledge of the supernatural, of God, and of the rational soul,[49] having given an admonition in his work "The Great Instauration", "that men confine the sense within the limits of duty in respect to things divine: for the sense is like the sun, which reveals the face of earth, but seals and shuts up the face of heaven". [39]

Advancement of Learning

"Of Proficience and Advancement of Learning Divine and Human" was published in 1605, and is written in the form of a letter to King James.

This book would be considered the first step in the Great Instauration scale, of "partitions of the sciences".

In this work, which is divided in two books, Bacon starts giving philosophical, civic and religious arguments for the engaging in the aim of advancing learning. In the second book, Bacon analyses the state of the sciences of his day, stating what was being done incorrectly, what should be bettered, in which way should they be advanced.

Among his arguments in the first book, he considered learned kingdoms and rulers to be higher than the unlearned, evoked as example King Solomon, the biblical king who had established a school of natural research, and gave discourses on how knowledge should be used for the "glory of the Creator" and "the relief of man's estate", if only it was governed by charity.

In the second book, he divided human understanding in three parts: history, related to man's faculty of memory; poetry, related to man's faculty of imagination; and philosophy, pertaining to man's faculty of reason. Then he considers the three aspects with which each branch of understanding can relate itself to: divine, human and natural. From the combination of the three branches (history,poetry and philosophy) and three aspects (divine, human and natural) a series of different sciences can be deduced.

He divided History in: divine history, or the History of religion; human or political history; and Natural History.

Poetry he divided in: narrative (natural/historical) poetry; dramatic (human) poetry, the kind of which "the ancients used to educate the minds of men to virtue"; and divine (parabolic) poetry, in which "the secrets and mysteries of religion, policy, and philosophy are involved in fables or parables".

Philosophy he divided in: divine, natural and human, which he referred to as the triple character of the power of God, the difference of nature, and the use of man.

Further on, he divided divine philosophy in natural theology (or the lessons of God in Nature) and revealed theology (or the lessons of God in the sacred scriptures), and natural philosophy in physics, metaphysics, mathematics (which included music, astronomy, geography, architecture, engineering), and medicine. For human philosophy, he meant the study of mankind itself, the kind of which leads to self-knowledge, through the study of the mind and the soul - which suggests resemblance with modern psychology.

He also took into consideration rhetoric, communication and transmission of knowledge.

The New Atlantis

In 1623, Bacon expressed his aspirations and ideals in New Atlantis. Released in 1627, this was his creation of an ideal land where "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit" were the commonly held qualities of the inhabitants of Bensalem. The name "Bensalem" means "son of peace",[50] having obvious resemblance with "Bethlehem" (birthplace of Jesus), and is referred to as "God's bosom, a land unknown", in the last page of the work.

In this utopian work, written in literary form, a group of Europeans travel west from Peru by boat. After having suffered with strong winds at sea and fearing for death, they "did lift up their hearts and voices to God above,beseeching him of his mercy".[31] After which, these travelers in a distant water finally reached the island of Bensalem, where they found a fair and well governed city, and were received kindly and with all humanity,by a christian and cultured people who had been converted centuries before by a miracle wrought by Saint Bartholomew, a few years after the Ascension of Jesus, by which the scriptures had reached them in a mysterious ark of cedar floating on the sea, guarded by a gigantic pillar of light over which was a cross of light.

Many aspects of the society and history of the island are described, such as the christian religion; a cultural feast in honor of the family institution, called "the Feast of the Family"; a college of sages, the Salomon's House, "the very eye of the kingdom", to which order "God of heaven and earth had vouchsafed the grace to know the works of Creation, and the secrets of them", as well as "to discern between divine miracles, works of nature, works of art, and impostures and illusions of all sorts"; and a series of instruments, process and methods of scientifical research that were employed in the island by the Salomon's House.[31]

The work also goes on interpreting the ancient fable of Atlantis, considering the lost island as actually being the American continent, which would have had much greater civilizations in the distant past than the ones at present suggest, but whose greatness and achievements were destroyed and covered by a terrible flood, the present american indians being just descendants of the more primitive people of the ancient civilization of Atlantis who had survived the flood because they lived apart of the civilization, in the mountains and high altitudes.

The inhabitants of Bensalem are described as having a high moral character and honesty, no official accepting any payment for their services from the visitors, and the people being described as chaste and pious, as said by an inhabitant of the island:

But hear me now, and I will tell you what I know. You shall understand that there is not under the heavens so chaste a nation as this of Bensalem; nor so free from all pollution or foulness. It is the virgin of the world. I remember I have read in one of your European books, of an holy hermit amongst you that desired to see the Spirit of Fornication; and there appeared to him a little foul ugly Aethiop. But if he had desired to see the Spirit of Chastity of Bensalem, it would have appeared to him in the likeness of a fair beautiful Cherubim. For there is nothing amongst mortal men more fair and admirable, than the chaste minds of this people. Know therefore, that with them there are no stews, no dissolute houses, no courtesans, nor anything of that kind. [...] And their usual saying is, that whosoever is unchaste cannot reverence himself; and they say, that the reverence of a man's self, is, next to religion, the chiefest bridle of all vices [31]

.

In the last third of the book, the Head of the Salomon's House takes one of the european visitors to show him all the scientific background of Salomon's House, where experiments are conducted in Baconian method in order to understand and conquer nature, and to apply the collected knowledge to the betterment of society. Namely: 1) the end of their foundation; 2) the preparations they have for their works; 3) the several employments and function whereto their fellows are assigned; 4) and the ordinances and rites which they observe.

Here he portrayed a vision of the future of human discovery and knowledge, and a practical demonstration of his method. The plan and organisation of his ideal college, "Salomon's House", envisioned the modern research university in both applied and pure science.

The end of their foundation is thus described: “The end of our foundation is the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible”.[31]

In describing the ordinances and rites observed by the scientists of Salomon's House, its Head said: “We have certain hymns and services, which we say daily, of Lord and thanks to God for His marvellous works; and some forms of prayer, imploring His aid and blessing for the illumination of our labors, and the turning of them into good and holy uses". [31]

(See Bacon's "Student's Prayer" and Bacon's "Writer's Prayer" )

There has been much speculation as to whether a real island society inspired Bacon's utopia. Scholars have suggested numerous countries, from Iceland to Japan; Dr. Nick Lambert highlighted the latter in The View Beyond.[51]

A city named "Bensalem" was actually founded in Pennsylvania, USA, in 1682.[52]

Valerius Terminus: of the interpretation of Nature

In this work of 1603, an argument for the progress of knowledge, Bacon considers the moral, religious and philosophical implications and requirements of the advancement of learning and the development of science. Although not as well-known as other works such as "Novum Organum" and "Advancement of Learning", this work's importance in Bacon's thought resides in the fact that it was the first of his scientific writings.

He opens the book, in the proem, stating his belief that the man who succeed in "kindling a light in nature", would be "the benefactor indeed of the human race, the propagator of man's empire over the universe, the champion of liberty, the conqueror and subduer of necessities" [53], and at the same time identifying himself as that man, saying he believed he "had been born for the service of mankind", and that in considering in what way mankind might best be served, he had found none so great as the discovery of new arts, endowments, and commodities for the bettering of man's life. [53]

In the first chapter, "Of the Limits and End of Knowledge", he outlines what he believed to be the limits and true ends of pursuing knowledge through sciences, in a similar way as he would later do in his book "The Great Instauration". He disavows both the knowledge and the power that is not dedicated to goodness or love, and as such, that all the power achieved by man through science must be subject to "that use for which God hath granted it; which is the benefit and relief of the state and society of man".

(See "Of the Limits and End of Knowledge" in Wikisource)

Further on, he also takes into consideration what were the present conditions in society and government that were preventing the advancement of knowledge.

In this book, Bacon considers the increase of knowledge in sciences not only as "a plant of God's own planting", but also as the fulfilling of a prophecy made by Daniel in the Old Testament:[54]

... "all knowledge appeareth to be a plant of God’s own planting, so it may seem the spreading and flourishing or at least the bearing and fructifying of this plant, by a providence of God, nay not only by a general providence but by a special prophecy, was appointed to this autumn of the world: for to my understanding it is not violent to the letter, and safe now after the event, so to interpret that place in the prophecy of Daniel where speaking of the latter times it is said, 'many shall pass to and fro, and science shall be increased' [Daniel 12:4]; as if the opening of the world by navigation and commerce and the further discovery of knowledge should meet in one time or age". [55]

This quoting from the Book of Daniel appears also, in the title page of Bacon's Instauratio Magna and Novum Organum, in latin: "Multi pertransibunt & augebitur scientia".[38]

Essays

"Essayes: Religious Meditations. Places of Perswasion and Disswasion. Seene and Allowed " was the first published book by Francis Bacon. The Essays are written in a wide range of styles, from the plain and unadorned to the epigrammatic. They cover topics drawn from both public and private life, and in each case the essays cover their topics systematically from a number of different angles, weighing one argument against another.

Though Bacon considered the Essays "but as recreation of my other studies", he was given high praise by his contemporaries. Later researches made clear the extent of Bacon's borrowings from the works of Montaigne, Aristotle and other writers, but the Essays have nevertheless remained in the highest repute. The 19th century literary historian Henry Hallam wrote that "They are deeper and more discriminating than any earlier, or almost any later, work in the English language".[56]

His essay "Of Gardens", in which Bacon says that "God Almighty first planted a Garden; and it is indeed the purest of human pleasures [...], the greatest refreshment to the spirits of man",[57] is said to have been influential in the history of English gardening, by Charles Quest-Ritson, who stated that it had enormous effect upon the imagination of subsequent garden owners in England. [58]

Above the symbolical statue of "Philosophy" in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., the quote "the inquiry, knowledge, and belief of truth is the sovereign good of human nature", from the chapter "Of Truth" appears.[59]

The Wisdom of the Ancients

"The Wisdom of the Ancients" [60] is a book written by Bacon in 1609, in which he takes ancient greek fables in an attempt to unveil their hidden meanings and teachings. He opens the Preface stating that fables are the poets' veiling of the "most ancient times that are buried in oblivion and silence".[61]

He believed to have found in 31 ancient fables, hidden teachings on varied issues such as moral, philosophy, religion, civility, politics, science, and art.

This work, not having a strict scientific nature as others more known works, has been reputed among Bacon's literary works.

One of the chapters in special, "Cupid or the Atom", may be worthy of adding to Bacon's scientific philosophy, for analysing the hidden meaning of the fable of Cupid, he shows in it his vision on the nature of the atom, and therefore, of matter itself. He states that 'Love' is the force or "instinct" of primal matter, "the natural motion of the atom", "the summary law of nature, that impulse of desire impressed by God upon the primary particles of matter which makes them come together, and which by repetition and multiplication produces all the variety of nature", "a thing which mortal thought may glance at, but can hardly take in". [62]

(See "Wisdom of the Ancients" in Wikisource)

An Advertisement Touching a Holy War

This treatise, that are among those which were published after Bacon's death and were left unfinished, is written in the form of debate. In it, there are six characters, each representing a sector of society: Eusebius, Gamaliel, Zebedeus, Martius, Eupolis and Pollio, representing respectively: a moderate divine, a Protestant zealot, a Roman Catholic zealot, a military man, a politic, and a courtier.

In the work, the six characters debate on whether it is lawful or not for Christendom to engage in a "Holy War" against infidels, such as the Turks. The work being left unfinished, not coming to a conclusive answer to the question in debate.

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker have argued, based on this treatise, that Bacon was not as idealistic as his utopian works suggest, rather that he was what might today be considered an advocate of genocidal eugenics. They see in it a defense of the elimination of detrimental societal elements by the English and compared this to the endeavours of Hercules while establishing civilised society in ancient Greece. [63] The work itself, however, being a dialogue, expresses both militarists and pacifists discourses debating each other, and doesn't come to any conclusion, since it was left unfinished.

Laurence Lampert has interpreted Bacon's treatise An Advertisement Touching a Holy War as advocating "spiritual warfare against the spiritual rulers of European civilisation."[64] Although this interpretation might be considered symbolical, for there is no hint of such an advocation in the work itself.

The work was dedicated to Lancelot Andrews, Bishop of Winchester and counselor of estate to King James.

Bacon's Personal Views on War and Peace

While Bacon's personal views on war and peace might be dubious in some writings, he thus expressed it in a letter of advices to Sir George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham:

"For peace and war, and those things which appertain to either; I in my own disposition and profession am wholly for peace, if please God to bless his kingdom therewith, as for many years past he hath done [...] God is the God of peace; it is one of his attributes, therefore by him alone must we pray, and hope to continue it: there is the foundation. [...] (Concerning the establishment of colonies in the 'New World') To make no extirpation of the natives under pretence of planting religion: God surely will no way be pleased with such sacrifices." [65]

Theological Tracts and Meditationes Sacrae

Less-known collections of Bacon's religious meditations and prayers, that were published in different volumes (one after his death and the other in 1597).

Among the prayers of his Theological Tracts are:[66]

- A Prayer, or Psalm, made by the Lord Bacon, Chancellor of England

- A Prayer made and used by the Lord Chancellor Bacon

- The Student's Prayer

- The Writer's Prayer

- A Confession of Faith

Among the texts of his Sacred Meditations: [67]

- Of The Works of God and Man

- Of The Miracles of our Saviour

- Of The Innocence of the Dove, and the Wisdom of the Serpent

- Of The Exaltation of Charity

- Of The Moderation of Cares

- Of Earthly Hope

- Of Hypocrites

- Of Impostors

- Of Several kinds of imposture

- Of Atheism

- Of Heresies

- Of The Church and the Scriptures

Translation of Certain Psalms into English verse

Published in 1625 and considered to be the last of his writings, Bacon translated 7 of the Psalms of David (numbers 1,12,90,104,125,137,149) to English in verse form, in which he shows his poetical skills.

Juridical works

Bacon was also a jurist by profession, having written some works for the reform of English Law. His legal work is considered to be in accordance to Natural Law, having being influenced by legislators such as Cicero and Justinian.[68]

He considered Law's fundamental tasks to be:

- To secure men's persons from death;

- To dispose the property of their goods and lands;

- For preservation of their good names from shame and infamy. [69]

One of his lines of argument, was that the law is the guardian of the rights of the people, and therefore should be simplified so every man could understand, as he expressed in a public speech in February 26, 1593:

Laws are made to guard the rights of the people, not to feed the lawyers. The laws should be read by all, known to all. Put them into shape, inform them with philosophy, reduce them in bulk, give them into every man's hand.[70]

Basil Montagu, a later British jurist influenced by his legal work, characterized him as a "cautious, gradual, confident, permanent reformer", always based on his "love of excellence".[71] Bacon suggested improvements both of the civil and criminal law; he proposed to reduce and compile the whole law; and in a tract upon universal justice, “Leges Legum”, he planted a seed, which according to Montagu, had not been dormant in the two following centuries. He was attentive to the ultimate and to the immediate improvement of the law, the ultimate improvement depending upon the progress of knowledge, and the immediate improvement upon the knowledge by its professors in power, of the local law, the principles of legislation, and general science. [71]

Among lawyers, Bacon was probably best known for his genius at stating the principles and philosophy of the law in concise, memorable, and quotable aphorisms, and for his efforts as Lord Chancellor to strengthen equity jurisprudence and check the power of the common law judges. As Lord Chancellor under James I, Sir Francis Bacon presided over the equity courts as the “Keeper of the King’s Conscience.” In this role he frequently came into conflict with Sir Edward Coke, who headed up the common law courts.[72]

Influence

Science

Bacon's ideas were influential in the 1630s and 1650s among scholars, in particular Sir Thomas Browne, who in his encyclopaedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–1672) frequently adheres to a Baconian approach to his scientific enquiries. During the Restoration, Bacon was commonly invoked as a guiding spirit of the Royal Society founded under Charles II in 1660.[73][74] In the nineteenth century his emphasis on induction was revived and developed by William Whewell, among others. He has been reputed as the "Father of Experimental Science".[75]

Bacon is also considered to be the philosophical influence behind the dawning of the Industrial age. In his works, Bacon always proposed that all scientific work should be done for charitable purposes, as matter of alleviating mankind's misery, and that therefore science should be practical and has as purpose the inventing of useful things for the relief of mankind's estate. This changed the course of science in history, from a merely contemplative state, as it was found in ancient and medieval ages, to a practical, inventive state - that would have eventually led to the inventions that made possible the Industrial Revolution.[76]

In his Instauratio Magna(1620), Bacon expressed the purpose of having the “spring of a progeny of Inventions, which shall overcome, to some extent, and subdue our needs and miseries”, [39] considering the primary business of science to overcome poverty, instead of mere intellectual pursuing.[77]

He also wrote a long treatise on Medicine, History of Life and Death,[78] with natural and experimental observations for the prolongation of life.

For one of his biographers, Hepworth Dixon, Bacon's influence in modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something. [79]

North America

Some authors [who?] believe that Bacon's vision for a Utopian New World in North America was laid out in his novel New Atlantis, which depicts a mythical island, Bensalem, located somewhere between Peru and Japan. In this work he depicted a land where there would be freedom of religion - showing a Jew treated fairly and equally in an island of Christians, but it has been debated whether this work had influenced others reforms, such as greater rights for women, the abolition of slavery, elimination of debtors' prisons, separation of church and state, and freedom of political expression,[80][81][82][83] although there is no hint of these reforms in The New Atlantis itself. His propositions of legal reform (which were not established in his life time), though, are considered to have been one of the influences behind the Napoleonic Code,[84] and therefore could show some resemblance with or influence in the drafting of others liberal constitutions that came in the centuries after Bacon's lifetime, such as the American.

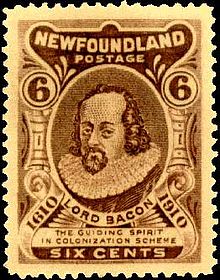

Francis Bacon played a leading role in creating the British colonies, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Newfoundland in northeastern Canada. His government report on “The Virginia Colony” was submitted in 1609. In 1610 Bacon and his associates received a charter from the king to form the Tresurer and the Companye of Adventurers and planter of the Cittye of London and Bristoll for the Collonye or plantacon in Newfoundland[85] and sent John Guy to found a colony there. In 1910 Newfoundland issued a postage stamp to commemorate Bacon's role in establishing the province. The stamp describes Bacon as, "the guiding spirit in Colonization Schemes in 1610."[18] Moreover, some scholars believe he was largely responsible for the drafting, in 1609 and 1612, of two charters of government for the Virginia Colony.[86] Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and author of the Declaration of Independence, wrote: "Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences".[87] Historian and biographer William Hepworth Dixon considered that Bacon's name could be included in the list of Founders of the United States of America.[88]

It is also believed by the Rosicrucian organization AMORC, that Bacon would have influenced in a settlement of mystics in North America, stating that his work "The New Atlantis" inspired a colony of Rosicrucians led by Johannes Kelpius, to journey accross the Atlantic Ocean in a chartered vessel called Sarah Mariah, and move on to Pennsylvania in late XVII Century. According to their claims, these rosicrucian communities "made valuable contributions to the newly emerging American culture in the fields of printing, philosophy, the sciences and arts". [89]

Johannes Kelpius and his fellows moved to Wissahickon Creek, in Pennsylvania, and became known as "Hermits of Mystics of the Wissahickon" [90] or simply "Monks of the Wissahickon".[91][92]

Law

Although much of his legal reform proposals were not established in his life time, his legal legacy was considered by the magazine New Scientist, in a publication of 1961, as having influenced the drafting of the Code Napoleon, and the law reforms introduced by Sir Robert Peel.[93]

The historian William Hepworth Dixon referred to the Code Napoleon as "the sole embodiment of Bacon's thought", saying that Bacon's legal work "has had more success abroad than it has found at home", and that in France "it has blossomed and come into fruit". [84]

The scholar Harvey Wheeler attributed to Bacon, in his work "Francis Bacon’s Verulamium - the Common Law Template of The Modern in English Science and Culture", the creation of these distinguishing features of the modern common law system:

- Using cases as repositories of evidence about the "unwritten law”;

- Determining the relevance of precedents by exclusionary principles of evidence and logic;

- Treating opposing legal briefs as adversarial hypotheses about the application of the "unwritten law" to a new set of facts.

As late as the eighteenth-century some juries still declared the law rather than the fact, but already before the end of the seventeenth century Sir Matthew Hale explained modern common law adjudication procedure and acknowledged Bacon as the inventor of the process of discovering unwritten laws from the evidences of their applications. The method combined empiricism and inductivism in a new way that was to imprint its signature on many of the distinctive features of modern English society. [94]

In brief, Bacon is considered by some jurists to be the father of modern Jurisprudence [68].

Political scientist James McClellan, from the University of Virginia, considered Bacon to have had "a great following" in the American colonies. [72]

Historical debates

Bacon and Shakespeare

The Baconian theory of Shakespearean authorship, first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Sir Francis Bacon wrote the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare, in opposition to the scholarly consensus that William Shakespeare of Stratford was the author.

Occult theories

Francis Bacon often gathered with the men at Gray's Inn to discuss politics and philosophy, and to try out various theatrical scenes that he admitted writing.[95] Bacon's alleged connection to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons has been widely discussed by authors and scholars in many books.[96] However others, including Daphne du Maurier (in her biography of Bacon), have argued there is no substantive evidence to support claims of involvement with the Rosicrucians.[97] Frances Yates[98] does not make the claim that Bacon was a Rosicrucian, but presents evidence that he was nevertheless involved in some of the more closed intellectual movements of his day. She argues that Bacon's movement for the advancement of learning was closely connected with the German Rosicrucian movement, while Bacon's New Atlantis portrays a land ruled by Rosicrucians. He apparently saw his own movement for the advancement of learning to be in conformity with Rosicrucian ideals.[99]

The link between Bacon's work and the Rosicrucians ideals which Yates allegedly found, was the conformity of the purposes expressed by the Rosicrucian Manifestos and Bacon's plan of a "Great Instauration",[99] for the two were calling for a reformation of both "divine and human understanding",[100][101] as well as both had in view the purpose of mankind's return to the "state before the Fall".[102][103]

Another major link is said to be the resemblance between Bacon's "New Atlantis" and the german rosicrucian Johann Valentin Andreae's "Description of the Republic of Christianopolis (1619)".[104] In his book, Andreae shows an utopic island in which christian theosophy and applied science ruled, and in which the spiritual fulfillment and intellectual activity constituted the primary goals of each individual, the scientific pursuits being the highest intellectual calling - linked to the acchievment of spiritual perfection. Andreae's island also depicts a great advancement in technology, with many industries separated in different zones which supplied the population's needs - which shows great resemblance with Bacon's scientific methods and purposes.[105] [76]

The Rosicrucian organization AMORC claims that Francis Bacon was the "Imperator" (leader) of the Rosicrucian Order in both England and the European continent, and would have directed it at that time of the Renaissance. [89]

Francis Bacon's influence can also be seen on a variety of religious and spiritual authors, and on groups that have utilised his writings in their own belief systems.[106][107][108][109][110]

See also

- Baconian method

- Scientific method

- Novum Organum Scientiarum

- Pseudodoxia Epidemica

- Francis Bacon School

- Cestui que (Defense and Comment on Chudleigh's Case)

- New Atlantis

- Essays (Francis Bacon)

- Bacon's cipher

- Code Napoleon

- Occult theories about Francis Bacon

Bibliography

A complete chronological Bibliography of Francis Bacon. (Many of Bacon's writings were only published after his death in 1626).

- Notes on the State of Christendom (1582)

- Letter of Advice to the Queen (1585-6)

- An Advertisement Touching the Controversies of the Church of England (1586-9)

- Dumb show in the Gray’s Inn Christmas Revels (1587-8)

- Misfortunes of Arthur (1588)

- A Conference of Pleasure : In Praise of Knowledge, In Praise of Fortitude, In Praise of Love, In Praise of Truth. (1592)

- Certain Observations made upon a Libel (1592)

- Temporis Partus Maximus (‘The Greatest Birth of Time’) (1593)

- A True Report of the Detestable Treason intended by Dr Roderigo Lopez (1594)

- The Device of the Indian Prince : Squire, Hermit, Soldier, Statesman. (1594)

- Gray’s Inn Christmas/New Year Revels: The High and Mighty Prince Henry, Prince of Purpoole ( 1594-5) (See Gesta Grayorum)

- The Honourable Order of the Knights of the Helmet (1595)(See Gesta Grayorum)

- The Sussex Speech (1595)

- The Philautia Device (1595)

- Maxims of the Law (1596)

- Essays (1st ed.) (1597)

- The Colours of Good and Evil (1597)

- Meditationes Sacrae (1597)

- Declaration of the Practices and Treasons attempted and Committed by the late Earl of Essex (1601)

- Valerius Terminus of the Interpretation of Nature (1603)

- A Brief Discourse touching the Happy Union of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland (1603)

- Cogitations de Natura Rerum (‘Thoughts on the Nature of Things’) (1604)

- Apologie concerning the late Earl of Essex (1604)

- Certain Considerations touching the better pacification and Edification of the Church of England (1604)

- The Advancement and Proficience of Learning Divine and Human (1605)

- Temporis Masculus Partus (‘The Masculine Birth of Time’) (1605)

- Filium Labyrinthi sive Formula Inquisitionis (1606)

- In Felicem Memoriam Elizabethae (‘In Happy Memory of Queen Elizabeth’) (1606)

- Cogitata et Visa de Interpetatione Naturae (‘Thoughts and Conclusions on the Interpretation of Nature’) (1607)

- Redargiutio Philosophiarum (‘The Refutation of Philosophies’) (1608)

- The Plantation of Ireland (1608-9)

- De Sapientia Veterum (‘Wisdom of the Ancients’) (1609)

- Descriptio Globi Intellectualis (‘A Description of the Intellectual Globe’) (1612)

- Thema Coeli (‘Theory of the Heavens’) (1612)

- Essays (2nd edition –38 essays) (1612)

- Marriage of the River Thames to the Rhine (masque performed by Gray's Inn and Inner Temple lawyers on the river and in Westminster Hall in celebration of the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Frederick, Elector Palatine) (1613)

- Charge…touching Duels (1614)

- The Masque of Flowers (performed by Gray's Inn before the King at Whitehall to honour the marriage of the Earl of Somerset to Frances Howard, Countess of Essex) (1614)

- Instauratio Magna ('Great Instauration') (1620)

- Novum Organum Scientiarum (‘New Method’) (1620)

- Historia Naturalis (‘Natural History’) (1622)

- Introduction to six Natural Histories (1622)

- Historia Ventorum (‘History of Winds’) (1622)

- History of the Reign of King Henry VII (1622)

- Abcedarium Naturae (1622)

- De Augmentis Scientiarum (1623)

- Historia Vitae et Mortis (‘History of Life and Death’) (1623)

- Historia Densi et Rari (‘History of Density and Rarity’) (1623)

- Historia Gravis et Levis (‘History of Gravity and Levity’) (1623)

- History of the Sympathy and Antipathy of Things (1623)

- History of Sulphur, Salt and Mercury (1623)

- A Discourse of a War with Spain (1623)

- An Advertisement touching an Holy War (1623)

- A Digest of the Laws of England (1623)

- Cogitationes de Natura Rerum (‘Thoughts on the Nature of Things’) (1624)

- De Fluxu et Refluxu Maris (‘Of the Ebb and Flow of the Sea’) (1624)

- Essays, or Counsels Civil and Moral (3rd/final edition – 58 essays) (1625)

- Apothegms New and Old (1625)

- Translation of Certain Psalms into English Verse (1625)

- Revision of De Sapientia Veterum (‘Wisdom of the Ancients’) (1625)

- Inquisitio de Magnete (‘Enquiries into Magnetism’) (1625)

- Topica Inquisitionis de Luce et Lumine (‘Topical Inquisitions into Light and Luminosity’) (1625)

All the following works were published only after his death (1626):

- New Atlantis (1627)

- Sylva Sylvarum, or Natural History (1627)

- Certain Miscellany Works (1629)

- Use of the Law (1629)

- Elements of the Common Laws (1629)

- Operum Moralium et Civilium (1638)

- Dialogum de Bello Sacro (1638)

- Cases of Treason (1641)

- Confession of Faith (1641)

- Speech concerning Naturalisation (1641)

- Office of Constables (1641)

- Discourse concerning Church Affairs (1641)

- An Essay of a King (1642)

- The Learned Reading of Sir Francis Bacon (to Gray’s Inn) (1642)

- Ordinances (1642)

- Relation of the Poisoning of Overbury. (1651)

- Scripta in Naturali et Universali Philosophia (1653)

- Scala Intellectus sive Filum Labyrinthi (1653)

- Prodromi sive Anticipationes Philosophiae Secundae (1653)

- Cogitationes de Natura Rerum (1653)

- De Fluxu et Refluxu Maris (1653)

- The Mirror of State and Eloquence (1656)

- Opuscula Varia Posthuma, Philosophica, Civilia et Theologia (1658)

- Letter of Advice to the Duke of Buckingham (1661)

- Charge given for the Verge (1662)

- Baconiana, Or Certain Genuine Remains Of Sr. Francis Bacon (1679)

- Abcedarium Naturae, or a Metaphysical piece (1679)

- Letters and Remains (1734)

- Promus (1861)

Notes

- ^ Complete Peerage, under Saint Alban, second edition; also Saint Albans, like the town and the three similar titles. The spelling differs even in authoritative contemporary sources, such as the Grant Book, and between the two editions of the Complete Peerage.

- ^ www.psychology.sbc.edu/Empiricism.htm

- ^ Contemporary spelling, used by Bacon himself in his letter of thanks to the king for his elevation. Birch, Thomas (1763). Letters, Speeches, Charges, Advices, &c of Lord Chancellor Bacon. Vol. 6. London: Andrew Millar. pp. 271–2. OCLC 228676038.

- ^ "Bacon, Francis (BCN573F)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Collins, Arthur (1741). The English Baronetage: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the English Baronets, Now Existing: Their Descents, Marriages, and Issues; Memorable Actions, Both in War, and Peace; Religious and Charitable Donations; Deaths, Places of Burial and Monumental Inscriptions [sic]. Printed for Tho. Wotton at the Three Daggers and Queen's Head. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Peltonen, Markku (October 2007). "Bacon, Francis, Viscount St Alban (1561–1626)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "History of Parliament". Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Spedding, James. "The letters and life of Francis Bacon" (1861).

- ^ http://publish.ucc.ie/celt/docs/E600001-015

- ^ a b c d Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (Yale University Press, 1996)

- ^ Matthews (1996: 56–57)

- ^ a b Rawley, William (1670). The Life of the Right Honorable Francis Bacon Baron of Verulam, Viscount ST. Alban. London: Thomas Johns,, London.

- ^ Peltonen in the ODNB states that the viscountcy was styled St Alban, but many other sources, including Burke and Debrett, use the name of Bacon's parliamentary constituency: then St Alban's

- ^ Parris, Matthew (2004). "Francis Bacon—1621". Great Parliamentary Scandals. London: Chrysalis. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781861057365.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Zagorin, Perez (1999). Francis Bacon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780691009667.

- ^ Historian A. L. Rowse, quoted in Parris; Maguire (2004: 8): "a charge of sodomy was...to be brought against the sixty-year-old Lord Chancellor".

- ^ Montagu, Basil (1837). Essays and Selections. pp. 325, 326. ISBN 978-1436837774.

- ^ a b Alfred Dodd, Francis Bacon's Personal Life Story', Volume 2 – The Age of James, England: Rider & Co., 1949, 1986. pages 157 – 158, 425, 502 – 503, 518 – 532

- ^ Alice Chambers Bunten, Life of Alice Barnham, Wife of Sir Francis Bacon, London: Oliphants Ltd. 1928.

- ^ Oliver Lawson Dick, ed. Aubrey's Brief Lives. Edited from the Original Manuscripts, 1949, s.v. "Francis Bacon, Viscount of St. Albans" p. 11.

- ^ See opposing opinions of: A. L. Rowse, Homosexuals in History, New York: Carroll & Garf, 1977. page 44; Jardine, Lisa; Stewart, Alan Hostage To Fortune: The Troubled Life of Francis Bacon Hill & Wang, 1999. page 148; Nieves Mathews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination, Yale University Press, 1996; Ross Jackson, The Companion to Shaker of the Speare: The Francis Bacon Story, England: Book Guild Publishing, 2005. pages 45 – 46

- ^ A. L. Rowse, Homosexuals in History, New York: Carroll & Garf, 1977. page 44

- ^ Jardine, Lisa; Stewart, Alan Hostage To Fortune: The Troubled Life of Francis Bacon Hill & Wang, 1999. page 148

- ^ Charles R. Forker, Masculine Love, Renaissance Writing, and the New Invention of Homosexuality: An Addendum in the Journal of Homosexuality (1996), Indiana University

- ^ Journal of Homosexuality, Volume: 31 Issue: 3, 1996, pages 85–93, ISSN: 0091-8369

- ^ Fulton Anderson, Francis Bacon:His career and his thought, Los Angeles, 1962