Four Pests campaign

The Four Evils campaign (Chinese: 除四害; pinyin: Chú Sì Hài) was one of the first campaigns of the Great Leap Forward in Maoist China from 1958 to 1962. Authorities targeted four "pests" for elimination: rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. The extermination of sparrows – also known as the smash sparrows campaign[1] (Chinese: 打麻雀运动; pinyin: dǎ máquè yùndòng) or the eliminate sparrows campaign (Chinese: 消灭麻雀运动; pinyin: xiāomiè máquè yùndòng) – resulted in severe ecological imbalance, and was one of the causes of the Great Chinese Famine which lasted from 1959 to 1961, with an estimated death toll due to starvation that ranges in the tens of millions (15 to 55 million).[note 1] The most stricken provinces were Anhui (18% dead), Chongqing (15%), Sichuan (13%), Guizhou (11%) and Hunan (8%).[11] In 1960, the campaign against sparrows ended, and bed bugs became an official target.

Background

[edit]The failure of food production during the Great Leap Forward was due to newly mandated agricultural practices imposed by the state. The mismanagement in agriculture can be attributed to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In December 1958, Mao Zedong formulated the "Eight Elements Constitution". Purportedly to be scientifically sound, the eight elements were intended to enable the nation to achieve the grain output goals of the Great Leap Forward. The eight methods were integrated into the CCP Central Committee's Resolution National Economic Plan which directed new agricultural practices throughout China. Contrary to expectations, these "scientific elements" had a detrimental impact on food production as they led to ecosystem collapse.

One proposed solution was labeled "pest control," with sparrows identified by Mao as pests. In response to the CCP's directive, local governments nationwide mobilized people to combat these birds. When the campaign against sparrows was eventually halted in April 1960, the unchecked proliferation of insects in the fields resulted in significant crop damage due to the absence of natural predators.[12] Approximations indicate that both the government and the general public were accountable for the demise of 1.5 billion rats, 1 billion sparrows, over 220 million pounds of flies, and over 24 million pounds of mosquitoes.[13]

Significance

[edit]"Man must conquer nature"

[edit]The Four Pests Campaign is representative of many of the overarching themes of Mao's Great Leap Forward. In order to expedite China's industrialization, and to achieve a socialist utopia, Mao sought to utilize China's natural and human resources. In this future utopia, cleanliness and hygiene would be critical.[14] For the Four Pests Campaign, ridding the country of rats, mosquitos, flies, and sparrows required mass mobilization of the Chinese population in order to change the natural world. Mao's slogan, ren ding sheng tian, meaning "man must conquer nature", became the rallying cry for the campaign.[14] This new ideology was a departure from the Daoist philosophy of finding a harmonious balance between mankind and nature. Under the campaign, the new philosophy was utilizing China's massive supply of manpower to subdue nature for the benefit of the country and its people.

Mass mobilization through propaganda

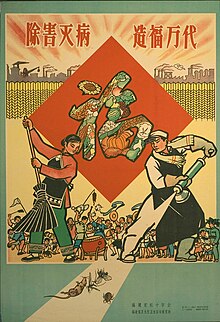

[edit]In an attempt to accomplish the significant task of changing the ecological order, Mao mobilized the entire Chinese population above the age of 5. Eye-catching propaganda, in which children featured prominently, were employed to encourage the population to contribute towards the socialist transformation. A firsthand account from a former Sichuan schoolchild at the time of the campaign recounted, "It was fun to 'Wipe out the Four Pests'. The whole school went to kill sparrows. We made ladders to knock down their nests, and beat gongs in the evenings, when they were coming home to roost."[15]

The propaganda posters offered no scientific explanation for why the campaign was necessary. Instead, they featured dramatic depictions of children heroically exterminating the pests, and hence playing their role in the Great Leap Forward. The propaganda served to frame the campaign as more than an effort to improve hygiene. The campaign was militaristic in nature, drawing on Chinese patriotism.[16] Similar to a coordinated military campaign, schoolchildren would disperse into the countryside at a specific hour to hunt sparrows.[15] On a particular poster it reads, "eradicate pests and diseases and build happiness for ten thousand generations".[17] Therefore, the potential result of this campaign was framed as grandiose, and with potential benefits that would last for generations.

Campaign

[edit]This section is missing information about bed bug control strategy, if any. (December 2023) |

The Four Pests Campaign in post-revolutionary China targeted rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows based on specific perceived threats to public health and agriculture. Rats, carriers of diseases with the potential to transmit illnesses to humans, were deemed a significant hazard to public health and were known to inflict damage on stored grains, posing a direct threat to agricultural productivity. Flies, recognized as vectors for disease transmission, were prevalent in both urban and rural areas, presenting a widespread health risk associated with unsanitary conditions. Mosquitoes, particularly those breeding in stagnant water, were identified as carriers of diseases such as malaria, posing a direct threat to public health. Sparrows, held responsible for consuming substantial quantities of grain, were targeted to address concerns about food shortages and protect agricultural yields. The campaign's strategic focus on these four pests was aligned with broader national goals, including improving public health, sanitation, and agricultural productivity.

However, the campaign's implementation and the subsequent unintended ecological consequences would come to underscore the complexity of balancing pest control initiatives with environmental sustainability.[1]

Rats

[edit]The Four Pests Campaign implemented a multifaceted approach to control rat populations. The large-scale use of rat poison played a pivotal role, with poisoned baits strategically distributed in both urban and rural areas to effectively target rats.[18] Complementary to this poisoning strategy, an extensive implementation of traps was employed, providing a localized method to capture and eliminate rats, thereby augmenting the broader impact of the poison campaign. Furthermore, citizens were actively encouraged to enlist the natural predatory instincts of cats in controlling rat populations. Recognizing cats as effective hunters and deterrents, this measure sought to harness feline assistance as a complementary means to address the pervasive rat issue during the campaign.

Sparrows

[edit]Sparrows became the focal point of an extermination campaign during the Four Pests initiative, because the government said they were a significant threat to grain stores. In an effort to reduce sparrow populations on a large scale, citizens were mobilized to participate in a mass extermination campaign.[19] To further deter sparrows from consuming grain, people actively engaged in creating loud noises, disrupting the birds and making it challenging for them to rest.[20] Simultaneously, the campaign encouraged the destruction of sparrow nests as a means to impede their reproduction, contributing to the broader objective of decreasing sparrow populations. Employing drastic measures aligned with the campaign's overarching goal, shooting sparrows using guns and other methods was implemented to achieve a significant reduction in their numbers.

Flies

[edit]The Four Pests Campaign employed a multifaceted strategy to address fly populations, with the widespread use of chemical insecticides serving as a key component. Public spaces and known breeding grounds were systematically targeted with insecticide sprays, aiming to curtail the spread of diseases associated with flies.[21] Complementing this chemical approach, a comprehensive public education campaign was initiated to promote cleanliness and proper waste disposal, targeting the root causes of fly breeding sites and serving as a synergistic measure alongside insecticide efforts to reduce fly infestations. Additionally, the strategic placement of traps designed to capture and contain flies in public spaces further diversified the campaign's toolkit for controlling fly populations, especially in areas where traditional insecticides may be less effective. This combined approach reflected a concerted effort to combat the health hazards posed by flies through a blend of chemical interventions and community-wide education and prevention initiatives.

Mosquitoes

[edit]The Four Pests Campaign strategically addressed the issue of mosquitoes through a variety of approaches. Focusing on the elimination of stagnant water, identified as a prime breeding ground for mosquitoes, the campaign aimed to reduce mosquito populations by improving water drainage systems.[22] This measure targeted the core habitat of mosquitoes, seeking to disrupt their reproductive cycle. Concurrently, the campaign extended the use of insecticides to areas prone to mosquito infestations. By strategically spraying insecticides in locations identified as mosquito breeding grounds, the campaign aimed to contribute significantly to the overarching goal of diminishing mosquito populations and mitigating the spread of diseases associated with these vectors. This combined strategy underscored the campaign's comprehensive efforts to address the public health threat posed by mosquitoes at both the larval and adult stages of their life cycle.

Timeline

[edit]- 1957: Before Initiation First proposed by Mao in the Third Plenary Session of the 8th CPC Central Committee.

- 1958: Initial Planning The idea for the Four Pests Campaign was proposed in 1958 as part of the Great Leap Forward, a large-scale economic and social campaign initiated by the Chinese government.

- 1958–1959: Pilot Programs Pilot programs were initiated in various cities to test the effectiveness of the measures against the four pests.[23]

- 1959–1960: Nationwide Implementation The campaign was officially launched nationwide in 1959. People were mobilized to participate in the extermination efforts against rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows.

- 1960–1961: Intensification and Ecological Consequences The campaign intensified during these years, with widespread efforts to eliminate the targeted pests. However, the mass killing of sparrows, in particular, had severe ecological consequences, leading to an increase in crop-eating insects.

- 1961: Official End of the Campaign In 1961, the Chinese government officially declared the end of the Four Pests Campaign. By this time, it was evident that the campaign had led to ecological imbalances and contributed to widespread famine.

Purpose

[edit]During the Great Leap Forward, a socio-economic campaign initiated by the Chinese government in the late 1950s with the ambitious goal of rapidly transforming the country from an agrarian society to an industrialized socialist nation, a key focus was placed on increasing agricultural production.[24] In an attempt to safeguard grain crops and boost food output, the government identified sparrows as a perceived threat to the harvest. Believing that these birds were responsible for significant grain losses, a nationwide campaign to exterminate sparrows was launched. Unfortunately, this approach proved to be a misguided endeavor as it disrupted the ecological balance. Sparrows played a crucial role in pest control by feeding on insects harmful to crops. The unintended consequences of the sparrow extermination contributed to ecological imbalances and exacerbated the challenges faced by Chinese agriculture during this period, ultimately highlighting the complexities involved in agricultural improvement initiatives.

In the realm of public health, government initiatives often aim to enhance overall population well-being. One such initiative has historically focused on the extermination of flies and mosquitoes as a means of improving public health.[13] This strategy is particularly crucial in regions where these insects serve as carriers of diseases, with a primary emphasis on combating malaria. By targeting and reducing the populations of flies and mosquitoes, the government seeks to minimize the transmission of diseases and subsequently improve the health of the population. Malaria, a mosquito-borne infectious disease, poses a significant threat to public health in many parts of the world. Government-led efforts to control and eradicate disease-carrying vectors, such as mosquitoes, contribute to the prevention and mitigation of health risks, reflecting a commitment to fostering a healthier and more resilient society. It underscores the importance of proactive measures in safeguarding public health and reducing the burden of preventable diseases on communities.

Social mobilization during the Great Leap Forward in China was marked by a dual approach of encouragement and coercion, with the government endeavoring to instigate widespread citizen participation in ambitious socio-economic endeavors. Aligned with the central tenets of the Great Leap Forward, this mobilization sought to reinforce mass engagement and collective effort towards rapid economic transformation.[25] Citizens were both urged and compelled to take part in extensive projects such as communal farming and backyard steel production through propaganda campaigns promoting allegiance to the state's vision. However, the coercive aspects of this mobilization, while driven by socialist ideals, led to unintended consequences such as resource mismanagement and unrealistic expectations. This complex interplay between state-driven initiatives and the push for mass participation underscored the challenges inherent in the pursuit of rapid socio-economic change during this historical period.

The political ideology during the specified period in China was characterized by the utilization of extensive campaigns to promote a proactive government under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This era, notably associated with Mao Zedong's leadership, witnessed an assertive stance on the part of the CCP, emphasizing the centralization of power and the consolidation of authority.[26] Propaganda campaigns played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape, promoting the idea of a proactive government as the driving force behind the nation's progress. Furthermore, the political ideology of the time saw a strengthening of Mao's cult of personality, where he was portrayed as the visionary leader guiding the country towards prosperity. The combination of proactive governance, assertive authority, and the cult of personality contributed to the shaping of China's political landscape during this period, leaving a lasting impact on the nation's history.

Consequences

[edit]While the campaign achieved its immediate goal of reducing disease transmission via the killing of rats, flies, and mosquitoes, the mass extermination of sparrows disrupted the delicate ecological balance. With the sparrow population devastated, locust populations soared uncontrollably, leading to devastating crop losses.[17]

The ecological repercussions translated into a humanitarian crisis of unprecedented proportions. The absence of sparrows, which traditionally kept locust populations in check, allowed swarms to ravage fields of grain and rice. The resulting agricultural failures, compounded by misguided policies of the Great Leap Forward, triggered a severe famine from 1958 to 1962. The death toll from starvation during this period reached 20 to 30 million people,[17] underscoring the high human cost of the ecological mismanagement inherent in the "Four Pests" campaign.

Although the sparrow campaign ended in disaster, the other three anti-pest campaigns may have contributed to the improvement in the health statistics in the 1950s.[27]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bikul, Harry (2022-03-18). "China's Smash Sparrows Campaign and Nature's Revenge!". Thought Might. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (18 December 1999). "China's great famine: 40 years later". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 319 (7225): 1619–1621. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1127087. PMID 10600969.

- ^ Gráda, Cormac Ó (2007). "Making Famine History". Journal of Economic Literature. 45 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1257/jel.45.1.5. hdl:10197/492. ISSN 0022-0515. JSTOR 27646746. S2CID 54763671.

- ^ Meng, Xin; Qian, Nancy; Yared, Pierre (2015). "The Institutional Causes of China's Great Famine, 1959–1961" (PDF). Review of Economic Studies. 82 (4): 1568–1611. doi:10.1093/restud/rdv016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Hasell, Joe; Roser, Max (10 October 2013). "Famines". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Dikötter, Frank. "Mao's Great Famine: Ways of Living, Ways of Dying" (PDF). Dartmouth University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Mirsky, Jonathan (7 December 2012). "Unnatural Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (1 January 2013). "China's Great Famine: the true story". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "China's Great Famine: A mission to expose the truth". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Huang, Zheping (10 March 2016). "Charted: China's Great Famine, according to Yang Jisheng, a journalist who lived through it". Quartz. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Cao 2005was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Chen, Yixin (2009). "Cold War Competition and Food Production in China, 1957-1962". Agricultural History. 83 (1): 51–78. doi:10.3098/ah.2008.83.1.51. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 20454912. PMID 19618528.

- ^ a b "The Four Pests Campaign: Objectives, Execution, Failure, And Consequences". WorldAtlas. 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ a b Steinfeld, Jemimah (September 2018). "China's deadly science lesson: How an ill-conceived campaign against sparrows contributed to one of the worst famines in history". Index on Censorship. 47 (3): 49. doi:10.1177/0306422018800259. ISSN 0306-4220.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Judith (2001). Mao's war against nature: politics and the environment in Revolutionary China. Studies in environment and history (1. publ ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-78150-3.

- ^ Holst, Abigail Li (April 12, 2016). "Chinese Propaganda Posters in Mao's Patriotic Health Movements: From Four Pests to SARS". etd.library.emory.edu. p. 3. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Paved With Good Intentions: Mao Tse-Tung's "Four Pests" Disaster". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ Yin, Chuang-Cheng; He, Yong; Zhou, Dong-Hui; Yan, Chao; He, Xian-Hui; Wu, Song-Ming; Zhou, Yang; Yuan, Zi-Guo; Lin, Rui-Qing; Zhu, X. Q. (2010). "Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Rats in Southern China". The Journal of Parasitology. 96 (6): 1233–1234. doi:10.1645/GE-2610.1. ISSN 0022-3395. JSTOR 40962069. PMID 21158644. S2CID 207250971.

- ^ "中共中央、国务院关于除四害讲卫生的指示_中国经济网——国家经济门户". www.ce.cn. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ "RED CHINA: Death to Sparrows". Time. 1958-05-05. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ Weatherley, Robert (2022). Mao's China And Post-mao China: Revolution, Recovery And Rejuvenation. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 48.

- ^ Schmalzer, Sigrid (2016). Red Revolution, Green Revolution: Scientific Farming in Socialist China. University of Chicago Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-226-33029-7.

- ^ Huang, Yanzhong (2015). Governing Health in Contemporary China. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-136-15548-2.

- ^ Chan, Alfred L. (March 1992). "The Campaign for Agricultural Development in the Great Leap Forward: A Study of Policy-Making and Implementation in Liaoning". The China Quarterly. 129: 52–71. doi:10.1017/S0305741000041229. ISSN 1468-2648. S2CID 154571426.

- ^ "Great Leap Forward", Wikipedia, 2023-12-04, retrieved 2023-12-08

- ^ "Mao Zedong - Chinese Revolution, Communism, Chairman | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ Benson, Linda (2013). China Since 1949. Taylor & Francis. p. 32.

External links

[edit]- China's Smash Sparrows Campaign And Nature's Revenge!

- PBS series The People's Century – 1949: The Great Leap

- China follows Mao with mass cull (BBC)

- Catastrophic Miscalculations