Hypostatic abstraction

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2022) |

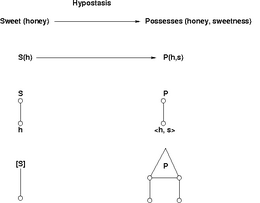

Hypostatic abstraction in philosophy and mathematical logic, also known as hypostasis or subjectal abstraction, is a formal operation that transforms a predicate into a relation; for example "Honey is sweet" is transformed into "Honey has sweetness". The relation is created between the original subject and a new term that represents the property expressed by the original predicate.

Description

[edit]Technical definition

[edit]Hypostasis changes a propositional formula of the form X is Y to another one of the form X has the property of being Y or X has Y-ness. The logical functioning of the second object Y-ness consists solely in the truth-values of those propositions that have the corresponding abstract property Y as the predicate. The object of thought introduced in this way may be called a hypostatic object and in some senses an abstract object and a formal object.

The above definition is adapted from the one given by Charles Sanders Peirce.[1] As Peirce describes it, the main point about the formal operation of hypostatic abstraction, insofar as it operates on formal linguistic expressions, is that it converts a predicative adjective or predicate into an extra subject, thus increasing by one the number of "subject" slots—called the arity or adicity—of the main predicate.

The distinction between particular objects and a formal object is noted by Anthony Kenny:[2] we might identify any object as having a certain property to which we respond, but the formal object of that response is the property which we implicitly ascribe to the particular object by virtue of us having that response: thus if a certain red rose is "lovely", the rose has the property of loveliness, and this loveliness is the formal object of our aesthetic appreciation of the rose.[3]

Application

[edit]

The grammatical trace of this hypostatic transformation is a process that extracts the adjective "sweet" from the predicate "is sweet", replacing it by a new, increased-arity predicate "possesses", and as a by-product of the reaction, as it were, precipitating out the substantive "sweetness" as a second subject of the new predicate.

The abstraction of hypostasis takes the concrete physical sense of "taste" found in "honey is sweet" and ascribes to it the formal metaphysical characteristics in "honey has sweetness".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ CP 4.235, "The Simplest Mathematics" (1902), in Collected Papers, CP 4.227–323

- ^ Kenny, A. (1963), Action, Emotion and Will, London, New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul; Humanities Press

- ^ Scarantino, A. and de Sousa, R., "Emotion", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), accessed on 4 December 2024

Sources

[edit]- Peirce, C.S. Hartshorne, Charles; Weiss, Paul (eds.). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vols. 1–6 (1931–1935). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Peirce, C.S. Burks, Arthur W. (ed.). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vols. 7–8 (1958). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Zeman, J. Jay (1982). "Peirce on Abstraction". The Monist. 65 (2): 211–229. doi:10.5840/monist198265210. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020 – via University of Florida.