Theobroma cacao

| Theobroma cacao | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cacao fruits on the tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Theobroma |

| Species: | T. cacao

|

| Binomial name | |

| Theobroma cacao | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Theobroma cacao (cacao tree or cocoa tree) is a small (6–12 m (20–39 ft) tall) evergreen tree in the family Malvaceae.[1][3] Its seeds - cocoa beans - are used to make chocolate liquor, cocoa solids, cocoa butter and chocolate.[4] Although the tree is native to the tropics of the Americas, the largest producer of cocoa beans in 2022 was Ivory Coast. The plant's leaves are alternate, entire, unlobed, 10–50 cm (4–20 in) long and 5–10 cm (2–4 in) broad.

Description

[edit]Flowers

[edit]The flowers are produced in clusters directly on the trunk and older branches; this is known as cauliflory. The flowers are small, 1–2 cm (3⁄8–13⁄16 in) diameter, with pink calyx. The floral formula, used to represent the structure of a flower using numbers, is ✶ K5 C5 A(5°+52) G(5).[5]

While many of the world's flowers are pollinated by bees (Hymenoptera) or butterflies/moths (Lepidoptera), cacao flowers are pollinated by tiny flies, Forcipomyia biting midges.[6][7] Using the natural pollinator Forcipomyia midges produced more fruit than using artificial pollinators.[7]

Fruit

[edit]The fruit, called a cacao pod, is ovoid, 15–30 cm (6–12 in) long and 8–10 cm (3–4 in) wide, ripening yellow to orange, and weighs about 500 g (1 lb) when ripe. The pod contains 20 to 60 seeds, usually called "beans", embedded in a white pulp.

The seeds are the main ingredient of chocolate, while the pulp is used in some countries to prepare refreshing juice, smoothies, jelly, and cream. Usually discarded until practices changed in the 21st century, the fermented pulp may be distilled into an alcoholic beverage.[8] Each seed contains a significant amount of fat (40–50%) as cocoa butter.

The fruit's active constituent is the stimulant theobromine, a compound similar to caffeine.[9]

Nomenclature

[edit]The generic name Theobroma is derived from the Greek for "food of the gods"; from θεός (theos), meaning 'god' or 'divine', and βρῶμα (broma), meaning 'food'. The specific name cacao is the Hispanization of the name given to the plant in indigenous Mesoamerican languages such as kakaw in Tzeltal, Kʼicheʼ and Classic Maya; kagaw in Sayula Popoluca; and cacahuatl in Nahuatl meaning "bean of the cocoa-tree".[10]

Taxonomy

[edit]Cacao (Theobroma cacao) is one of 26 species belonging to the genus Theobroma classified under the subfamily Byttnerioideae of the mallow family Malvaceae.[1]

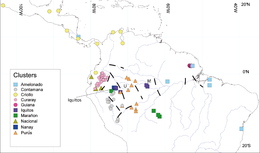

In 2008, researchers proposed a new classification based upon morphological, geographic, and genomic criteria: 10 groups have been named according to their geographic origin or the traditional cultivar name. These groups are: Amelonado, Criollo, Nacional, Contamana, Curaray, Cacao guiana, Iquitos, Marañon, Nanay, and Purús.[11]

Distribution and domestication

[edit]T. cacao is widely distributed from southeastern Mexico to the Amazon basin. There were originally two hypotheses about its domestication; one said that there were two foci for domestication, one in the Lacandon Jungle area of Mexico and another in lowland South America.[citation needed] More recent studies of patterns of DNA diversity, however, suggest that this is not the case. One study sampled 1241 trees and classified them into 10 distinct genetic clusters.[11] This study also identified areas, for example around Iquitos in modern Peru and Ecuador, where representatives of several genetic clusters originated more than 5000 years ago, leading to development of the variety, Nacional cocoa bean.[12] This result suggests that this is where T. cacao was originally domesticated, probably for the pulp that surrounds the beans, which is eaten as a snack and fermented into a mildly alcoholic beverage.[13] Using the DNA sequences and comparing them with data derived from climate models and the known conditions suitable for cacao, one study refined the view of domestication, linking the area of greatest cacao genetic diversity to a bean-shaped area that encompasses Ecuador, the border between Brazil and Peru and the southern part of the Colombian–Brazilian border.[14] Climate models indicate that at the peak of the last ice age 21,000 years ago, when habitat suitable for cacao was at its most reduced, this area was still suitable, and so provided a refugium for species.

Cacao trees grow well as understory plants in humid forest ecosystems. This is equally true of abandoned cultivated trees, making it difficult to distinguish truly wild trees from those whose parents may originally have been cultivated.[citation needed]

Cultivation

[edit]

In 2016, cocoa beans were cultivated on roughly 10,200,000 hectares (25,000,000 acres) worldwide.[15] Cocoa beans are grown by large agroindustrial plantations and small producers, the bulk of production coming from millions of farmers with small plots.[16] A tree begins to bear when it is four or five years old. A mature tree may have 6,000 flowers in a year, yet only about 20 pods. About 1,200 seeds (40 pods) are required to produce 1 kg (2.2 lb) of cocoa paste.

Historically, chocolate makers have recognized three main cultivar groups of cacao beans used to make cocoa and chocolate: Forastero, Criollo and Trinitario.[17] The most prized, rare, and expensive is the Criollo group, the cocoa bean used by the Maya.[18] Only 10% of chocolate is made from Criollo, which is arguably less bitter and more aromatic than any other bean. In November 2000, the cacao beans coming from Chuao were awarded an appellation of origin under the title Cacao de Chuao (from Spanish: 'cacao of Chuao').[19]

The cacao bean in 80% of chocolate is made using beans of the Forastero group, the main and most ubiquitous variety being the Amenolado variety, while the Arriba variety (such as the Nacional variety) are less commonly found in Forastero produce. Forastero trees are significantly hardier and more disease-resistant than Criollo trees, resulting in cheaper cacao beans.[20]

Major cocoa bean processors include Hershey's, Nestlé and Mars. Chocolate can be made from T. cacao through a process of steps that involve harvesting, fermenting of T. cacao pulp, drying, harvesting, and then extraction.[21] Roasting T. cacao by using superheated steam was found to be better than conventional oven-roasting because it resulted in the same quality of cocoa beans in a shorter time.[21]

Production

[edit]| Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 2,230,000 | |

| 1,108,663 | |

| 667,296 | |

| 337,149 | |

| 300,000 | |

| 280,000 | |

| World | 5,874,582 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[22] | |

In 2022, world production of cocoa beans was 5.9 million tonnes, led by Ivory Coast with 38% of the total. Other major producers were Ghana (19%) and Indonesia (11%).

Conservation

[edit]The pests and diseases to which cacao is subject, along with climate change, mean that new varieties will be needed to respond to these challenges. Breeders rely on the genetic diversity conserved in field genebanks to create new varieties, because cacao has recalcitrant seeds that cannot be stored in a conventional genebank.[23] In an effort to improve the diversity available to breeders, and ensure the future of the field genebanks, experts have drawn up A Global Strategy for the Conservation and Use of Cacao Genetic Resources, as the Foundation for a Sustainable Cocoa Economy.[24] The strategy has been adopted by the cacao producers and their clients, and seeks to improve the characterization of cacao diversity, the sustainability and diversity of the cacao collections, the usefulness of the collections, and to ease access to better information about the conserved material. Some natural areas of cacao diversity are protected by various forms of conservation, for example national parks. However, a recent study of genetic diversity and predicted climates[14] suggests that many of those protected areas will no longer be suitable for cacao by 2050. It also identifies an area around Iquitos in Peru that will remain suitable for cacao and that is home to considerable genetic diversity, and recommends that this area be considered for protection. Other projects, such as the International Cocoa Quarantine Centre, aim to combat cacao diseases and preserve genetic diversity.

Phytopathogens (parasitic organisms) cause much damage to Theobroma cacao plantations around the world. Many of those phytopathogens, which include many of the pests named below, were analyzed using mass spectrometry and allow for guiding on the correct approaches to get rid of the specific phytopathogens. This method was found to be quick, reproducible, and accurate showing promising results in the future to prevent damage to Theobroma cacao by various phytopathogens.[25]

A specific bacterium Streptomyces camerooniansis was found to be beneficial for T. cacao by helping plant growth by accelerating seed germination of T. cacao, inhibiting growth of various types of microorganisms (such as different oomycetes, fungi, and bacteria), and preventing rotting by Phytophthora megakarya.[26]

Pests

[edit]Various plant pests and diseases can cause serious problems for cacao production.[27]

- Insects

- Cocoa mirids or capsids worldwide (but especially Sahlbergella singularis and Distantiella theobroma in West Africa and Helopeltis spp. in Southeast Asia)

- Bathycoelia thalassina - West Africa

- Conopomorpha cramerella (cocoa pod borer – in Southeast Asia)

- Carmenta theobromae - C. & S. America

- Fungi

- Moniliophthora roreri (frosty pod rot)

- Moniliophthora perniciosa (witches' broom)

- Ceratocystis cacaofunesta (mal de machete) or (Ceratocystis wilt)

- Verticillium dahliae

- Oncobasidium theobromae (vascular streak dieback)

- Oomycetes

- Phytophthora spp. (black pod) especially Phytophthora megakarya in West Africa

- Viruses

- Mistletoe

- Rats and other vertebrate pests (squirrels, woodpeckers, etc.)

Genome

[edit] Map showing genetic clusters of Theobroma cacao | |

| NCBI genome ID | 572 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 345.99 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 10 pairs |

| Year of completion | 2010 |

The genome of T. cacao is diploid, its size is 430 Mbp, and it comprises 10 chromosome pairs (2n=2x=20). In September 2010, a team of scientists announced a draft sequence of the cacao genome (Matina1-6 genotype).[28] In a second, unrelated project, the International Cocoa Genome Sequencing Consortium-ICGS, coordinated by CIRAD,[29] first published[30] in December 2010 (online, paper publication in January 2011), the sequence of the cacao genome, of the Criollo cacao (of a landrace from Belize, B97-61/B2). In their publication, they reported a detailed analysis of the genomic and genetic data.

The sequence of the cacao genome identified 28,798 protein-coding genes, compared to the roughly 23,000 protein-coding genes of the human genome. About 20% of the cacao genome consists of transposable elements, a low proportion compared to other plant species. Many genes were identified as coding for flavonoids, aromatic terpenes, theobromine and many other metabolites involved in cocoa flavor and quality traits, among which a relatively high proportion code for polyphenols, which constitute up to 8% of cacao pods dry weight. The cacao genome appears close to the hypothetical hexaploid ancestor of all dicotyledonous plants,[31] and it is proposed as an evolutionary mechanism by which the 21 chromosomes of the dicots' hypothetical hexaploid ancestor underwent major fusions leading to cacao's 10 chromosome pairs.

The genome sequence enables cacao molecular biology and breeding for elite varieties through marker-assisted selection, in particular for genetic resistance to fungal, oomycete and viral diseases responsible for huge yield losses each year. In 2017–18, due to concerns about survivability of cacao plants in an era of global warming in which climates become more extreme in the narrow band of latitudes where cacao is grown (20 degrees north and south of the equator), the commercial company, Mars, Incorporated and the University of California, Berkeley are using CRISPR to adjust DNA for improved hardiness of cacao in hot climates.[32]

History of cultivation

[edit]Domestication

[edit]The cacao tree, native of the Amazon rainforest, was first domesticated at least 5,300 years ago, in equatorial South America from the Santa Ana-La Florida (SALF) site in what is present-day southeast Ecuador (Zamora-Chinchipe Province) by the Mayo-Chinchipe culture before being introduced in Mesoamerica.[33]

In Mesoamerica, ceramic vessels with residues from the preparation of cacao beverages have been found from the Early Formative (1900–900 BC) period. For example, one such vessel found at an Olmec archaeological site on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico dates cacao's preparation by pre-Olmec peoples as early as 1750 BC.[34] On the Pacific coast of Chiapas, Mexico, a Mokaya archaeological site provides evidence of even earlier cacao beverages, to 1900 BC.[34] The initial domestication was probably related to the making of a fermented alcoholic beverage.[35] In 2018, researchers who analysed the genome of cultivated cacao trees concluded that the domesticated cacao trees all originated from a single domestication event that occurred about 3,600 years ago somewhere in Central America.[36]

Ancient uses

[edit]Several mixtures of cacao are described in ancient texts, for ceremonial or medicinal, as well as culinary, purposes. Some mixtures included maize, chili, vanilla (Vanilla planifolia), and honey. Archaeological evidence for use of cacao, while relatively sparse, has come from the recovery of whole cacao beans at Uaxactun, Guatemala[37] and from the preservation of wood fragments of the cacao tree at Belize sites including Cuello and Pulltrouser Swamp.[38] In addition, analysis of residues from ceramic vessels has found traces of theobromine and caffeine in early formative vessels from Puerto Escondido, Honduras (1100–900 BC) and in middle formative vessels from Colha, Belize (600–400 BC) using similar techniques to those used to extract chocolate residues from four classic period (around 400 AD) vessels from a tomb at the Maya archaeological site of Rio Azul. As cacao is the only known commodity from Mesoamerica containing both of these alkaloid compounds, it seems likely these vessels were used as containers for cacao drinks. In addition, cacao is named in a hieroglyphic text on one of the Rio Azul vessels. Cacao is also believed to have been ground by the Aztecs and mixed with tobacco for smoking purposes.[citation needed] Cocoa was being domesticated by the Mayo Chinchipe of the upper Amazon around 3,000 BC.[39]

The Maya believed the kakaw (cacao) was discovered by the gods in a mountain that also contained other delectable foods to be used by them. According to Maya mythology, the Plumed Serpent gave cacao to the Maya after humans were created from maize by divine grandmother goddess Xmucane.[40] The Maya celebrated an annual festival in April to honor their cacao god, Ek Chuah, an event that included the sacrifice of a dog with cacao-colored markings, additional animal sacrifices, offerings of cacao, feathers and incense, and an exchange of gifts. In a similar creation story, the Mexica (Aztec) god Quetzalcoatl discovered cacao (cacahuatl: "bitter water"), in a mountain filled with other plant foods.[41] Cacao was offered regularly to a pantheon of Mexica deities and the Madrid Codex depicts priests lancing their ear lobes (autosacrifice) and covering the cacao with blood as a suitable sacrifice to the gods. The cacao beverage was used as a ritual only by men, as it was believed to be an intoxicating food unsuitable for women and children.[42]

Cacao beans constituted both a ritual beverage and a major currency system in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations. At one point, the Aztec empire received a yearly tribute of 980 loads (Classical Nahuatl: xiquipilli) of cacao, in addition to other goods. Each load represented exactly 8,000 beans.[43] The buying power of quality beans was such that 80–100 beans could buy a new cloth mantle. The use of cacao beans as currency is also known to have spawned counterfeiters during the Aztec empire.[44]

-

kakaw (cacao) written in the Maya script

-

Sculpture of a man carrying a cacao pod. Aztec, 1440-1521 AD

-

A cacao tree in the Aztec Codex Fejérváry-Mayer

Modern history

[edit]

The first European knowledge about chocolate came in the form of a beverage which was first introduced to the Spanish at their meeting with Moctezuma in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1519.[citation needed] Cortés and others noted the vast quantities of this beverage the Aztec emperor consumed, and how it was carefully whipped by his attendants beforehand. Examples of cacao beans, along with other agricultural products, were brought back to Spain at that time, but it seems the beverage made from cacao was introduced to the Spanish court in 1544 by Kekchi Maya nobles brought from the New World to Spain by Dominican friars to meet Prince Philip.[46] Within a century, chocolate had spread to France, England and elsewhere in Western Europe. Demand for this beverage led the French to establish cacao plantations in the Caribbean, while Spain subsequently developed their cacao plantations in their Venezuelan and Philippine colonies (Bloom 1998, Coe 1996).[47] A painting by Dutch Golden Age artist Albert Eckhout shows a wild cacao tree in mid-seventeenth century Dutch Brazil. The Nahuatl-derived Spanish word cacao entered scientific nomenclature in 1753 after the Swedish naturalist Linnaeus published his taxonomic binomial system and coined the genus and species Theobroma cacao. Traditional pre-Hispanic beverages made with cacao are still consumed in Mesoamerica. These include the Oaxacan beverage known as tejate.

Gallery

[edit]-

Floral diagram showing partial inflorescence

-

Leaves, fruits and seed. A. Bernecker, 1864.

-

Young trees, Côte d'Ivoire

-

Macrophotography of flower (closed)

-

Macrophotography of flower (open)

-

Flowers

-

Cacao seed in the fruit or pocha

-

Fruit, dried

See also

[edit]- Ceratonia siliqua, the carob tree

- Kola nut

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Theobroma cacao L. Sp. Pl. : 782 (1753)". World Flora Online. World flora Consortium. 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Mentha canadensis L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Theobroma cacao". Encyclopedia of Life. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Cocoa". Drugs.com. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Ronse De Craene, Louis P. (4 February 2010). Floral Diagrams: An Aid to Understanding Flower Morphology and Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-521-49346-8. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Hernández B., J. (1965). "Insect pollination of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in Costa Rica". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ a b Forbes, Samantha J.; Northfield, Tobin D. (26 December 2016). "Increased pollinator habitat enhances cacao fruit set and predator conservation". Ecological Applications. 27 (3): 887–899. doi:10.1002/eap.1491. PMID 28019052. S2CID 6858627.

- ^ Bell, Katie K. "Cacao Cocktails: A New Tequila-Like Spirit Distilled from Cacao Fruit". Forbes. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Philip K. (2015). "Chocolate in Science, Nutrition and Therapy: A Historical Perspective". In Wilson, P.; Hurst, W. (eds.). Chocolate and Health: Chemistry, Nutrition and Therapy. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84973-912-2.

- ^ "Cacao". Etymology Online Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2018. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ a b Motamayor, Juan C.; Lachenaud, Philippe; da Silva e Mota, Jay Wallace; Loor, Rey; Kuhn, David N.; Brown, J. Steven; Schnell, Raymond J. (2008). "Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L.)". PLoS ONE. 3 (10): e3311. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3311M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003311. PMC 2551746. PMID 18827930.

- ^ "History of cocoa (translated)". National Association of Exporters and Industrialists of Cacao of Ecuador. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Clement, Charles R.; de Cristo-Araújo, Michelly; d'Eeckenbrugge, Geo Coppens; Alves Pereira, Alessandro; Picanço-Rodrigues, Doriane (6 January 2010). "Origin and Domestication of Native Amazonian Crops". Diversity. 2 (1): 72–106. doi:10.3390/d2010072. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ a b Thomas, Evert; van Zonneveld, Maarten; Loo, Judy; Hodgkin, Toby; Galluzzi, Gea; van Etten, Jacob; Fuller, Dorian Q. (24 October 2012). "Present Spatial Diversity Patterns of Theobroma cacao L. in the Neotropics Reflect Genetic Differentiation in Pleistocene Refugia Followed by Human-Influenced Dispersal". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e47676. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747676T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047676. PMC 3480400. PMID 23112832.

- ^ "Cocoa beans, area harvested in 2016, Crops/World regions/Cocoa beans/Area harvested from pick lists". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "A strategy to safeguard the future of chocolate". Bioversity International. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Varieties". All about Chocolate. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Lanaud, Claire; Vignes, Hélène; Utge, José; Valette, Gilles; Rhoné, Bénédicte; et al. (7 March 2024). "A revisited history of cacao domestication in pre-Columbian times revealed by archaeogenomic approaches". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 2972. Bibcode:2024NatSR..14.2972L. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-53010-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10920634. PMID 38453955.

- ^ "Branding Matters: The Success of Chuao Cocoa Bean". Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Kongor, John Edem; Hinneh, Michael; de Walle, Davy Van; Afoakwa, Emmanuel Ohene; Boeckx, Pascal; Dewettinck, Koen (1 April 2016). "Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean flavour profile — A review". Food Research International. 82: 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2016.01.012. ISSN 0963-9969.

- ^ a b Zzaman, Wahidu; Bhat, Rajeev; Yang, Tajul Aris; Mat Easa, Azhar (2 March 2017). "Influences of superheated steam roasting on changes in sugar, amino acid and flavor active components of cocoa bean (Theobroma cacao)". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 97 (13): 4429–4437. Bibcode:2017JSFA...97.4429Z. doi:10.1002/jsfa.8302. ISSN 1097-0010. PMID 28251656.

- ^ "Cocoa bean production in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Cacao Collections". CacaoNet. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Global Strategy – cacaonet". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Dos Santos, Fábio Neves; Tata, Alessandra; Belaz, Kátia Roberta Anacleto; Magalhães, Dilze Maria Argôlo; Luz, Edna Dora Martins Newman; Eberlin, Marcos Nogueira (1 March 2017). "Major phytopathogens and strains from cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) are differentiated by MALDI-MS lipid and/or peptide/protein profiles". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 409 (7): 1765–1777. doi:10.1007/s00216-016-0133-5. PMID 28028594. S2CID 3764608.

- ^ Boudjeko, Thaddée; Tchinda, Romaric Armel Mouafo; Zitouni, Mina; Nana, Joëlle Aimée Vera Tchatchou; Lerat, Sylvain; Beaulieu, Carole (4 March 2017). "Streptomyces cameroonensis sp. nov., a Geldanamycin Producer That Promotes Theobroma cacao Growth". Microbes and Environments. 32 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1264/jsme2.ME16095. ISSN 1347-4405. PMC 5371071. PMID 28260703.

- ^ "Cocoa Crop Protection". Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to the Cacao Genome Project – Cacao Genome Database". Cacaogenomedb.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ The International Cocoa Genome Sequencing Consortium federates efforts from circa 20 different institutions from six countries (France, USA, Côte d'Ivoire, Brazil, Venezuela and Trinidad et Tobago). Financing comes from several public and private sources from France, USA and Venezuela, among which the chocolate brands Valrhona (France) and Hershey's (USA). See : http://www.cirad.fr/actualites/toutes-les-actualites/communiques-de-presse/2010/decryptage-du-genome-du-cacaoyer Archived 16 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Argout, Xavier; Salse, Jerome; Aury, Jean-Marc; Guiltinan, Mark J.; Droc, Gaetan; Gouzy, Jerome; Allegre, Mathilde; Chaparro, Cristian; et al. (2011). "The genome of Theobroma cacao" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 43 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1038/ng.736. PMID 21186351. S2CID 4685532.

- ^ Jaillon, Olivier; Aury, Jean-Marc; Noel, Benjamin; Policriti, Alberto; Clepet, Christian; Casagrande, Alberto; et al. (2007). "The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla". Nature. 449 (7161): 463–467. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..463J. doi:10.1038/nature06148. hdl:11577/2430527. PMID 17721507.

- ^ Brodwin, Erin (31 December 2017). "Chocolate is on track to go extinct in 40 years". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Zarrillo, Sonia; Gaikwad, Nilesh; Lanaud, Claire; Powis, Terry; Viot, Christopher; Lesur, Isabelle; et al. (29 October 2018). "The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (12): 1879–1888. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2.1879Z. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0697-x. PMID 30374172. S2CID 53099825.

- ^ a b Powis, Terry G.; Hurst, W. Jeffrey; del Carmen Rodríguez, María; Ortíz C., Ponciano; Blake, Michael; Cheetham, David; Coe, Michael D.; Hodgson, John G. (December 2007). "Oldest chocolate in the New World". Antiquity. 81 (314). Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Henderson, J. S.; et al. (2007). "Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (48): 18937–18940. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708815104. PMC 2141886. PMID 18024588.

- ^ ""Cacao analysis dates the dawn of domesticated chocolate trees to 3,600 years ago", Eurekalert, October 24, 2018". Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Kidder (1947).

- ^ Hammond and Miksicek (1981); Turner and Miksicek (1984).

- ^ Davis, Nicola (29 October 2018). "Origin of chocolate shifts 1,400 miles and 1,500 years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ (Bogin 1997, Coe 1996, Montejo 1999, Tedlock 1985)

- ^ (Coe 1996, Townsend 1992)

- ^ Grivetti, Louis E.; Lowe, Diana Salazar; Jimenez, Martha; Escárcega, Sylvia; Barriga, Patricia; Dillinger, Teresa L. (1 August 2000). "Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (8): 2057S–72S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.8.2057S. PMID 10917925.

- ^ J. Bergmann (1969).

- ^ S. Coe (1994).

- ^ Head 1903, p. ii (frontispiece)

- ^ (Coe and Coe 1996)

- ^ Alexander Walker (1822). Colombia, relación geográfica, topográfica, agrícola, comercial y política de este país: adaptada para todo lector en general y para el comerciante y colono en particular. Tomo II. Londres: Banco de la República, pp. 284.

Sources

[edit]- Head, Brandon (1903). The Food of the Gods: A Popular Account of Cocoa. London: R. B. Johnson. p. ii.

Further reading

[edit]- Coe, Sophie D.; Coe, Michael D. (1996). The True History of Chocolate. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01693-3.

- Dienhart, John M. (1997). "The Mayan Languages – A Comparative Vocabulary" (PDF). Odense University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

- McNeil, Cameron, ed. (2006). Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-2953-8.

External links

[edit]- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) – includes cacao daily market prices and charts