For Greater Glory

| For Greater Glory | |

|---|---|

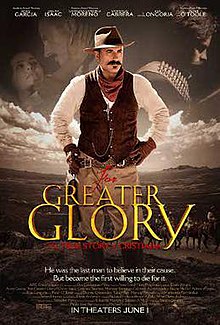

US Theatrical release Poster | |

| Directed by | Dean Wright |

| Written by | Michael James Love |

| Produced by | Pablo Jose Barroso |

| Starring | Andy García Oscar Isaac Catalina Sandino Moreno Santiago Cabrera Rubén Blades Bruce McGill Adrian Alonso Eva Longoria Peter O'Toole |

| Cinematography | Eduardo Martinez Solares |

| Edited by | Richard Francis-Bruce Mike Jackson |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | NewLand Films |

| Distributed by | ARC Entertainment (US) 20th Century Fox (Mexico) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 145 minutes |

| Country | Mexico |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million |

| Box office | $10,353,194 |

For Greater Glory: The True Story of Cristiada, also known as Cristiada and as Outlaws, is a 2012 epic historical war drama film[1] directed by Dean Wright and written by Michael Love, based on the events of the Cristero War.[2][3][4][5][6] It stars Andy García, Eva Longoria, Oscar Isaac, Rubén Blades, Peter O'Toole (in his last film appearance released in his lifetime), and Bruce Greenwood. The film is the directorial debut for Wright, a veteran visual effects supervisor on films including The Two Towers (2002) and The Return of the King (2003),[1] and was released on June 1, 2012.

Plot

[edit]The film opens with screen titles describing the anti-Catholic provisions of the 1917 Constitution of Mexico. Civil war erupts when newly elected Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles (Rubén Blades) begins a violent crackdown against the country's Catholic faithful. The film depicts the carnage by showing churches being set on fire, Catholic priests murdered, and countless faithful peasants killed and having their bodies publicly hanged on telegraph poles as a warning to others.

The story shifts to Father Christopher (Peter O’Toole), a Catholic priest, who is ruthlessly murdered by the Federales. A 13-year-old boy, José Luis Sánchez (Mauricio Kuri), witnesses the killing. Driven by love for his Faith and anger against the injustices committed against Fr. Christopher and the Church in Mexico, he joins the rebels, the Cristeros ("soldiers for Christ") fighting against Calles. Their battle cry is "¡Viva Cristo Rey!" ("Long live Christ the King"). The rebel leader, retired General Enrique Gorostieta (Andy García), an agnostic, takes an interest in young José, who soon becomes his protégé. While fighting against the Federales, José is later captured in a firefight and tortured to force him to renounce his belief in God. When he resolutely defends his faith, he is executed. The next year, Gorostieta is killed in a battle at Jalisco after he becomes a Catholic. In 1929, however, agreements were made to restore religious freedoms. Pope Benedict XVI beatified José in 2005, along with 12 other martyrs of the religious persecution.

Cast

[edit]- Andy García as Enrique Gorostieta[7]

- Eva Longoria as Tulita Gorostieta

- Mauricio Kuri as José Sánchez del Río

- Peter O'Toole as Father Christopher

- Oscar Isaac as Victoriano "El Catorce" Ramírez

- Santiago Cabrera as Father Vega

- Eduardo Verástegui as Anacleto González Flores

- Rubén Blades as President Plutarco Elías Calles

- Nestor Carbonell as Mayor Picazo

- Catalina Sandino Moreno as Adriana

- Bruce Greenwood as Ambassador Dwight Morrow

- Bruce McGill as President Calvin Coolidge

- Adrian Alonso as Lalo

- Joaquín Garrido as Minister Amaro

- Karyme Lozano as Doña María del Río

- Alma Martinez as Señora Vargas

- Andrés Montiel as Florentino Vargas

- Roger Cudney as Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg

Production

[edit]

The film is based on The Cristero Rebellion, the 1976 chronicle of the war written by French historian Jean Meyer who resides in Mexico.[8]

The filming started in May 2010 and shot for 12 weeks. Production took place between 31 May 2010 and 16 August 2010. The film was shot in Mexico City, Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Tlaxcala and Puebla. Including an ecological reserve, Sierra de Órganos National Park in the town of Sombrerete, Mexico.[9][10]

At one point the director recreates a famous photograph of the bodies of executed Cristeros hanging from telephone poles, but they are seen in the film from a moving train.

Release

[edit]The film had a robust opening in Mexico taking first place in gross admissions at the box office, and second in total receipts, behind Titanic 3D. As of May 11, 2012, it had grossed $2.2 million.[8][11][12]

Reception

[edit]The film has received negative reviews, noting its performances and ambition but criticizing the screenplay and presentation of events. As of 2021, it holds a 35% rating on Metacritic based on 17 critics,[13] and a 20% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 49 reviews.[14] The latter site states: "It has laudable aspirations, but For Greater Glory ultimately fails to fulfill its goals due to an overstuffed script, thinly written characters, and an overly simplified dramatization of historical events."

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two and a half stars, and concluded that "it is well-made, yes, but has such pro-Catholic tunnel vision I began to question its view of events."[15] Frank Scheck of The Hollywood Reporter criticized the film as being 'melodramatic' and 'overlong', but noted that 'Despite its profusion of violent battle sequences, the film is most effective in its quieter moments, such as the scenes in which Calles warily negotiates with the American ambassador (Bruce Greenwood) who is mainly intent on preserving U.S. oil interests'.[16] Nathan Rabin of The A.V. Club panned the film and called it, 'an endless, plodding educational tool of unusual bluntness and dull force, a blood-soaked primer on intolerance and religious persecution that would benefit from even the faintest tinge of moral ambiguity or narrative sophistication.'[17]

In more positive reviews, Stephen Holden of The New York Times described the film as an "old-fashioned, Hollywood-style epic" and said that it compared favorably to Christian mega-hits of the 1950s such as The Robe. He was most satisfied with Dean Wright, referring to his direction as "impressively spacious." The composer James Horner also scored high marks for his score, which Holden found "uplifting without being syrupy" and which set an "inspirational mood."[18] Phil Boatwright of the "Baptist Press" called the film "a compelling, thoughtful homage to religious freedom" and said that it brought back memories of El Cid and A Man for All Seasons.[11]

According to Steven D. Greydanus of Decent Films, For Greater Glory may help to change the obscurity of the Cristero War in the United States. He observed that the film is "one of the most lavish and ambitious films ever produced in Mexico" and "a sweeping, handsome epic with strong performances, solid production values and magnificent locations across Mexico." However, like several other reviewers, he found the screenplay overbearing and would have liked to have seen more character development.[19]

Accolades

[edit]The movie received the following awards and nominations:

At ALMA Awards 2012, got nominations:

- Favorite Movie

- Favorite Movie Actor - Andy García

- Favorite Movie Actress - Drama/Adventure - Eva Longoria

- Favorite Movie Actor - Supporting Role - Oscar Isaac

- Favorite Movie Actor - Supporting Role - Rubén Blades

At Ariel Awards 2013:

Nominated

- Silver Ariel Best Art Direction (Mejor Diseño de Arte)

- Salvador Parra

At Image Awards 2013:

Nominated

- Image Award Outstanding International Motion Picture

At Movieguide Awards 2013

Won

- Faith and Freedom Award

Won

- Grace Award - Most Inspiring Performance in Movies - Andy Garcia

Nominated

- Epiphany Prize - Most Inspiring Movie

Nominated

- Grace Award - Most Inspiring Performance in Movies

Mauricio Kuri [20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Young, James, "Cristiada welcomed in Durango", August 21, 2010, Variety

- ^ Joes, Anthony James, Resisting Rebellion, pp. 68, 69–80, University Press of Kentucky 2006: "The Cristero movement, called by Mexicans La Cristiada, fought against religious persecution by the regime in Mexico City."

- ^ Edmonds-Poli, Emily and David A. Shirk Contemporary Mexican Politics, p. 51, Rowman & Littlefield 2009: "Growing outrage at government restrictions and continued persecution of the clergy led to a series of uprisings in central Mexico known collectively as the Cristero rebellion."

- ^ Chand, Vikram K., Mexico's Political Awakening, p. 153, University of Notre Dame Press, 2001: "In 1926, the Catholic hierarchy had responded to government persecution by suspending Mass, which was then followed by the eruption of the Cristero War...."

- ^ Bethel, Leslie, Cambridge History of Latin America, p. 593, Cambridge Univ. Press: “The Revolution had finally crushed Catholicism and driven it back inside the churches, and there it stayed, still persecuted, throughout the 1930s and beyond.”

- ^ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo, Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People, p. 355, W. W. Norton & Company 1993: referring to the period: "With ample cause, the church saw itself as persecuted."

- ^ "Cast of For Greater Glory". Retrieved 5 February 2013. from official website.

- ^ a b Drake, Tim. "Mexican Catholics Fight for Christ in 'For Greater Glory' | News". NCRegister.com. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ "Filming Location Matching "Sierra%20de%20Organos,%20Sombrerete,%20Zacatecas,%20Mexico" (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)". IMDb.

- ^ "'For Greater Glory': Recalling Mexico's Cristeros War". The-tidings.com. 2012-05-11. Archived from the original on 2014-05-04. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ a b "Baptist Press - MOVIES: 'For Greater Glory' heralds religious freedom - News with a Christian Perspective". Bpnews.net. 2012-05-23. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Catholic Online (1929-06-02). "Cristiada - Film About an Unknown War Box Office Smash in Mexico - Movies & Theatre - Arts & Entertainment - Catholic Online". Catholic.org. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ "For Greater Glory Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More". Metacritic. 2012-06-01. Retrieved 2012-06-21.

- ^ "For Greater Glory (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (2012-05-30). "For Greater Glory". rogerebert.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-28. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ "For Greater Glory: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 31 May 2012.

- ^ "For Greater Glory". The A.V. Club. 31 May 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (2012-05-31). "'For Greater Glory' Traces Mexico's Cristero War - NYTimes.com". Movies.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ Greydanus, Steven D. "SDG Reviews 'For Greater Glory' | Daily News". NCRegister.com. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ^ "For Greater Glory: The True Story of Cristiada". IMDb.com. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Ferreira, Cornelia R. Blessed José Luis Sánchez del Rio: Cristero Boy Martyr, biography (2006, Canisius Books)

External links

[edit]- 2012 films

- Films about Catholic priests

- 2012 war drama films

- Films about Catholicism

- War epic films

- War drama films based on actual events

- Films scored by James Horner

- Cultural depictions of Calvin Coolidge

- Mexican war drama films

- 2012 directorial debut films

- 2012 drama films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s Mexican films

- English-language Mexican films

- English-language war drama films

- Cristero War films