Centrifugal governor

A centrifugal governor is a specific type of governor with a feedback system that controls the speed of an engine by regulating the flow of fuel or working fluid, so as to maintain a near-constant speed. It uses the principle of proportional control.

Centrifugal governors, also known as "centrifugal regulators" and "fly-ball governors", were invented by Christiaan Huygens and used to regulate the distance and pressure between millstones in windmills in the 17th century.[1][2] In 1788, James Watt adapted one to control his steam engine where it regulates the admission of steam into the cylinder(s),[3] a development that proved so important he is sometimes called the inventor. Centrifugal governors' widest use was on steam engines during the Steam Age in the 19th century. They are also found on stationary internal combustion engines and variously fueled turbines, and in some modern striking clocks.

A simple governor does not maintain an exact speed but a speed range, since under increasing load the governor opens the throttle as the speed (RPM) decreases.

Operation

[edit]

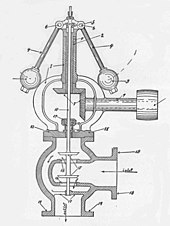

The devices shown are on steam engines. Power is supplied to the governor from the engine's output shaft by a belt or chain connected to the lower belt wheel. The governor is connected to a throttle valve that regulates the flow of working fluid (steam) supplying the prime mover. As the speed of the prime mover increases, the central spindle of the governor rotates at a faster rate, and the kinetic energy of the balls increases. This allows the two masses on lever arms to move outwards and upwards against gravity. If the motion goes far enough, this motion causes the lever arms to pull down on a thrust bearing, which moves a beam linkage, which reduces the aperture of a throttle valve. The rate of working-fluid entering the cylinder is thus reduced and the speed of the prime mover is controlled, preventing over-speeding.

Mechanical stops may be used to limit the range of throttle motion, as seen near the masses in the image at right.

Non-gravitational regulation

[edit]A limitation of the two-arm, two-ball governor is its reliance on gravity, and that the governor must stay upright relative to the surface of the Earth for gravity to retract the balls when the governor slows down.

Governors can be built that do not use gravitational force, by using a single straight arm with weights on both ends, a center pivot attached to a spinning axle, and a spring that tries to force the weights towards the center of the spinning axle. The two weights on opposite ends of the pivot arm counterbalance any gravitational effects, but both weights use centrifugal force to work against the spring and attempt to rotate the pivot arm towards a perpendicular axis relative to the spinning axle.

Spring-retracted non-gravitational governors are commonly used in single-phase alternating current (AC) induction motors to turn off the starting field coil when the motor's rotational speed is high enough.

They are also commonly used in snowmobile and all-terrain vehicle (ATV) continuously variable transmissions (CVT), both to engage/disengage vehicle motion and to vary the transmission's pulley diameter ratio in relation to the engine revolutions per minute.

History

[edit]

Centrifugal governors were invented by Christiaan Huygens and used to regulate the distance and pressure between millstones in windmills in the 17th century.[4][5]

James Watt designed his first governor in 1788 following a suggestion from his business partner Matthew Boulton. It was a conical pendulum governor and one of the final series of innovations Watt had employed for steam engines. A giant statue of Watt's governor stands at Smethwick in the English West Midlands.

Uses

[edit]Centrifugal governors' widest use was on steam engines during the Steam Age in the 19th century. They are also found on stationary internal combustion engines and variously fueled turbines, and in some modern striking clocks.

Centrifugal governors are used in many modern repeating watches to limit the speed of the striking train, so the repeater does not run too quickly.

Another kind of centrifugal governor consists of a pair of masses on a spindle inside a cylinder, the masses or the cylinder being coated with pads, somewhat like a centrifugal clutch or a drum brake. This is used in a spring-loaded record player and a spring-loaded telephone dial to limit the speed.

Dynamic systems

[edit]The centrifugal governor is often used in the cognitive sciences as an example of a dynamic system, in which the representation of information cannot be clearly separated from the operations being applied to the representation. And, because the governor is a servomechanism, its analysis in a dynamic system is not trivial. In 1868, James Clerk Maxwell wrote a famous paper "On Governors"[6] that is widely considered a classic in feedback control theory. Maxwell distinguishes moderators (a centrifugal brake) and governors which control motive power input. He considers devices by James Watt, Professor James Thomson, Fleeming Jenkin, William Thomson, Léon Foucault and Carl Wilhelm Siemens (a liquid governor).

Natural selection

[edit]In his famous 1858 paper to the Linnean Society, which led Darwin to publish On the Origin of Species, Alfred Russel Wallace used governors as a metaphor for the evolutionary principle:

The action of this principle is exactly like that of the centrifugal governor of the steam engine, which checks and corrects any irregularities almost before they become evident; and in like manner no unbalanced deficiency in the animal kingdom can ever reach any conspicuous magnitude, because it would make itself felt at the very first step, by rendering existence difficult and extinction almost sure soon to follow.[7]

The cybernetician and anthropologist Gregory Bateson thought highly of Wallace's analogy and discussed the topic in his 1979 book Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, and other scholars have continued to explore the connection between natural selection and systems theory.[8]

Culture

[edit]A centrifugal governor is part of the city seal of Manchester, New Hampshire in the US and is also used on the city flag. A 2017 effort to change the design was rejected by voters.[9]

A stylized centrifugal governor is also part of the coat of arms of the Swedish Work Environment Authority.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hills, Richard L (1996), Power From Wind, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Bellman, Richard E. (8 December 2015). Adaptive Control Processes: A Guided Tour. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400874668. Retrieved 13 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ University of Cambridge: Steam engines and control theory

- ^ Hills, Richard L (1996), Power From the Wind, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Bellman, Richard E. (8 December 2015). Adaptive Control Processes: A Guided Tour. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400874668. Retrieved 13 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Maxwell, James Clerk (1868). "On Governors". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 16: 270–283. doi:10.1098/rspl.1867.0055. JSTOR 112510.

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel. "On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type". Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- ^ Smith, Charles H. "Wallace's Unfinished Business". Complexity (publisher Wiley Periodicals, Inc.) Volume 10, No 2, 2004. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ^ Granite Geek: "Manchester city flag celebrates one of the coolest inventions from the Industrial Revolution – happily, they won’t change it"

External links

[edit] Media related to Centrifugal governors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Centrifugal governors at Wikimedia Commons