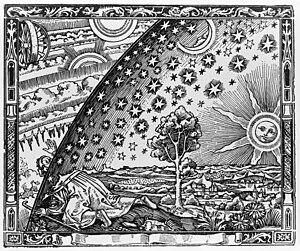

Flammarion engraving

The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist. Its first documented appearance is in the book L'atmosphère : météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology"), published in 1888 by the French astronomer and writer Camille Flammarion.[1][2] Several authors during the 20th century considered it to be either a Medieval or Renaissance artwork, but the current consensus is that it is a 19th century illustration that imitates older artistic styles and themes.[1]

The illustration depicts a man, dressed as a pilgrim in a long robe and carrying a walking stick, who has reached a point where the flat Earth meets the firmament. The pilgrim kneels down and passes his head, shoulders, right arm, and the top of the walking stick through an opening in the firmament, which is depicted as covered on the inside by the stars, Sun, and Moon. Behind the sky, the pilgrim finds a marvelous realm of circling clouds, fires and suns. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery resembles traditional pictorial representations of the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" described in the visions of the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel.[1]

The wood engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut.[1] It has been widely used as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge.[1][3] More recently, it has also been used as to represent a psychedelic experience.[4]

Attribution

[edit]

In the early 20th century, the scholar Heinz Strauss dated the image to the period 1520–30, while Heinrich Röttinger suggested that it had been made in 1530–60.[1] In 1957, historian of astronomy Ernst Zinner claimed that the image dated to the German Renaissance, but he was unable to find any version published earlier than 1906.[5] The same image was used by psychoanalyst Carl Jung in his 1959 book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. Jung speculated that the image was a Rosicrucian engraving from the 17th century.[3] The eminent art historian Erwin Panofsky also thought that illustration was from the 17th century, while his colleague Ernst Gombrich judged it to be modern.[1] In 1970, Jung's associate Marie-Louise von Franz reproduced and discussed the image in her book Number and Time, where it was captioned "The hole open to eternity, the spiritual pilgrim discovering another world".[3] Von Franz suggested that the image might be a 19th-century woodcut.[3]

The image was traced to Flammarion's book by Arthur Beer, an astrophysicist and historian of German science at Cambridge and, independently, by Bruno Weber, the curator of rare books at the Zürich central library.[6] Weber argued that the work was a composite of images characteristic of different historical periods, and that it had been made with a burin, a tool used for wood engraving only since the late 18th century.[1]

Flammarion had been apprenticed at the age of twelve to an engraver in Paris and it is believed that many of the illustrations for his books were engraved from his own drawings, probably under his supervision. Therefore, it is plausible that Flammarion himself created the image, though the evidence for this remains inconclusive. Like most other illustrations in Flammarion's books, the engraving carries no attribution. Although sometimes referred to as a forgery or a hoax, Flammarion does not characterize the engraving as a medieval or renaissance woodcut, and the mistaken interpretation of the engraving as an older work did not occur until after Flammarion's death. The decorative border surrounding the engraving is distinctly non-medieval and it was only by cropping it that the confusion about the historical origins of the image became possible.

According to Bruno Weber and to astronomer Joseph Ashbrook,[7] the depiction of a spherical heavenly vault separating the Earth from an outer realm is similar to an illustration that begins the first chapter of Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia, first published in 1544, a book which Flammarion, an ardent bibliophile and book collector, might have owned.[1] However, in 2002 Hans Gerhard Senger, an expert on the works of Nicholas of Cusa, argued against the image having been first created by Flammarion.[1]

Context in Flammarion's book

[edit]In Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, the image is accompanied by a caption in French, which translates as:

A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch...[2]

The illustration refers to the text on the facing page (p. 162), which also clarifies the author's intent in using it as an illustration:

Whether the sky be clear or cloudy, it always seems to us to have the shape of an elliptic arch; far from having the form of a circular arch, it always seems flattened and depressed above our heads, and gradually to become farther removed toward the horizon. Our ancestors imagined that this blue vault was really what the eye would lead them to believe it to be; but, as Voltaire remarks, this is about as reasonable as if a silk-worm took his web for the limits of the universe. The Greek astronomers represented it as formed of a solid crystal substance; and so recently as Copernicus, a large number of astronomers thought it was as solid as plate-glass. The Latin poets placed the divinities of Olympus and the stately mythological court upon this vault, above the planets and the fixed stars. Previous to the knowledge that the earth was moving in space, and that space is everywhere, theologians had installed the Trinity in the empyrean, the glorified body of Jesus, that of the Virgin Mary, the angelic hierarchy, the saints, and all the heavenly host.... A naïve missionary of the Middle Ages even tells us that, in one of his voyages in search of the terrestrial paradise, he reached the horizon where the earth and the heavens met, and that he discovered a certain point where they were not joined together, and where, by stooping his shoulders, he passed under the roof of the heavens...[8]

The same paragraph had already appeared, without the accompanying engraving, in an earlier edition of the text published under the title of L'atmosphère: description des grands phénomènes de la Nature ("The Atmosphere: Description of the Great Phenomena of Nature," 1872).[9] The correspondence between the text and the illustration is so close that one would appear to be based on the other. Had Flammarion known of the engraving in 1872, it seems unlikely that he would have left it out of that year's edition, which was already heavily illustrated. The more probable conclusion therefore is that Flammarion commissioned the engraving specifically to illustrate this particular text, though this has not been ascertained conclusively.

Possible literary sources

[edit]The idea of the contact of the Earth with a solid sky is one that repeatedly appears in Flammarion's earlier works. Commentators have suggested various literary passages that might have directly motivated the composition of the image in the Flammarion engraving. These included the Medieval legend of Saint Macarius the Roman, the Letters of François de La Mothe Le Vayer from the 17th century, and the classical argument for the infinitude of space attributed to Archytas of Tarentum (a friend of the philosopher Plato).

Legend of Saint Macarius

[edit]In his Les mondes imaginaires et les mondes réels ("Imaginary Worlds and Real Worlds", 1864), Flammarion cites a legend of a Christian saint, Macarius the Roman, which he dates to the 6th century. This legend includes the story of three monks (Theophilus, Sergius, and Hyginus) who "wished to discover the point where the sky and the earth touch"[10] (in Latin: ubi cœlum terræ se conjungit).[11] After recounting the legend[12] he remarks that "the preceding monks hoped to go to heaven without leaving the earth, to find 'the place where the sky and the earth touch,' and open the mysterious gateway which separates this world from the other. Such is the cosmographical notion of the universe; it is always the terrestrial valley crowned by the canopy of the heavens."

In the legend of St. Macarius, the monks do not in fact find the place where Earth and sky touch.

Letters of Le Vayer

[edit]In Les mondes imaginaires Flammarion recounts another story:

This fact reminds us of the tale which Le Vayer recounts in his Letters. It appears that an anchorite, probably a relative of the Desert Fathers of the East, boasted of having been as far as the end of the world, and of having been obliged to stoop his shoulders, on account of the joining of the sky and the earth in that distant place.[13]

Flammarion also mentioned the same story, in nearly the same words, in his Histoire du Ciel ("History of the Sky"):

"I have in my library," interrupted the deputy, "a very curious work: Levayer's letters. I recall having read there of a good anchorite who bragged of having been 'to the ends of the earth,' and of having been obliged to stoop his shoulders, because of the union of the sky and of the earth at this extremity."[14]

The Letters referred to are a series of short essays by François de La Mothe Le Vayer. In letter 89, Le Vayer, after mentioning Strabo's scornful opinion of Pytheas's account of a region in the far north where land, sea, and air seemed to mingle in a single gelatinous substance, adds:

That good anchorite, who boasted of having been as far as the end of the world, said likewise, that he had been obliged to stoop low, on account of the joining of the sky and earth in that distant region.[15]

Le Vayer does not specify who this "anchorite" was, nor does he provide further details about the story or its sources. Le Vayer's comment was expanded upon by Pierre Estève in his Histoire generale et particuliere de l'astronomie ("General and Particular History of Astronomy," 1755), where he interprets Le Vayer's statement (without attribution) as a claim that Pytheas "had arrived at a corner of the sky, and was obliged to stoop down in order not to touch it."[16]

The combination of the story of St. Macarius with Le Vayer's remarks seems to be due to Flammarion himself. It also appears in his Les terres du ciel ("The Lands of the Sky"):

With respect to the bounds (of the Earth)... some monks of the tenth century of our era, bolder than the rest, say that, in making a voyage in search of the terrestrial paradise, they had found the point where the heaven and earth touch, and had even been obliged to lower their shoulders![17]

Argument of Archytas

[edit]This historian of science Stefano Gattei has argued that the image in the engraving is directly inspired by an argument for the infinitude of space, due to the ancient Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum. Gattei quotes the version of this argument given in the commentary on Aristotle's Physics by Simplicius of Cilicia, written in the 6th century CE:

But Archytas, according to Eudemus, put the question in this way: "If I came to be at the edge, for example at the heaven of the fixed stars, could I stretch out my hand or walking stick, or not? It would be absurd that I could not stretch it out; but, if I do stretch it out, what is outside will be either body or place (it makes no difference, as we shall discover). Thus he will always go on in the same way to the newly chosen limit on each occasion, and ask the same question again. And if there is always something else into which the stick is stretched, it will clearly be also unlimited.[1]

Later uses and interpretations

[edit]1970s

[edit]The first color version to be published was made by Roberta Weir and distributed by Berkeley's Print Mint in 1970.[citation needed] That color image spawned most of the modern variations that have followed since.[citation needed] Donovan's 1973 LP, Cosmic Wheels, used an extended black and white version on its inner sleeve (an artist added elements extending the image to fit the proportions of the record jacket). The image also appeared in "The Compleat Astrologer" (pg. 25) by Derek and Julia Parker in 1971. In 1994, 'The Secret Language of Birthdays' by Gary Goldschneider and Joost Elffers was published featuring this image.[18]

The image was reproduced on the title page of the score of Brian Ferneyhough's "Transit: Six Solo Voices and Chamber Orchestra", published by Edition Peters in 1975.

British artist David Oxtoby made a drawing inspired by the Flammarion engraving (Spiritual Pilgrim), showing the face of David Bowie near the drawing's right margin where the Sun should be. David Oxtoby's drawing doesn't show the crawling man at left.[19]

1980s–2000s

[edit]The Flammarion engraving appeared on the cover of Daniel J. Boorstin's bestselling history of science The Discoverers, published in 1983. Other books devoted to science that used it as an illustration include The Mathematical Experience (1981) by Philip J. Davis and Reuben Hersh, Matter, Space, and Motion: Theories in Antiquity and Their Sequel (1988) by Richard Sorabji, Paradoxes of Free Will (2002) by Gunther Stent, and Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus and On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (2006) by William T. Vollmann. Some books devoted to mysticism which have also used the engraving include Love and Law (2001) by Ernest Holmes and Gnosticism: New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing (2002) by Stephan A. Hoeller.

The 1989 Dungeons & Dragons setting Spelljammer was loosely inspired by the Flammarion engraving at the suggestion of David "Zeb" Cook.[20]

The Brazilian writer Olavo de Carvalho reproduced the engraving in his 1995 book O Jardim das Aflições ("The Garden of Afflictions"), offering it as an example of Renaissance views concerning the spiritual world, which he criticized: "the pilgrim evades the mundane 'sphere', abandoning trees and flowers, Sun and Moon, birds and stars, to penetrate the marvelous kingdom of the spirit, which consists of some miserable gear wheels hidden among cloud wisps. Beautiful exchange!"[21]

2010s

[edit]An interpretation of the image was used for the animated sequence about the cosmological vision of Giordano Bruno in the March 9, 2014 premiere of the TV series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, hosted by the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson.

In the German-language video series "Von Aristoteles zur Stringtheorie", ("From Aristotle to String Theory"), which is hosted on YouTube and produced by Urknall, Weltall, und das Leben,[22] and features Professor Joseph Gaßner as lecturer, a colored Flammarion engraving was selected as a logo, but the man is peering at a background filled with the important equations of physics.

2020s

[edit]More recently in May 2021, an interpretation of the image has featured on a limited edition book release by Yusuf/Cat Stevens.[23]

Niklas Åkerblad also known as El Huervo, in October 2021 released an album titled "Flammarion" in which the cover art for the album depicts an interpretation of the original Flammarion engraving.

The 2018 TV show Lodge 49 shows the Flammarion engraving in its opening credits (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKCAqrSXM6I).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gattei, Stefano (2014). "An Original Fake: Closing the Debate on Flammarion's Engraving". In Beretta, Marco; Conforti, Maria (eds.). Fakes!?: Hoaxes, Counterfeits, and Deception in Early Modern Science. Sagamore Beach: Science History Publications/USA. pp. 206–265. ISBN 978-0-88135-495-9.

- ^ a b Flammarion, Camille (1888). L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire. Paris: Hachette. p. 163. The text is also available here Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d Browne, Laurence (2021). "The Flammarion Engraving and its Symbolic Potential". Psychological Perspectives. 64 (4): 562–580. doi:10.1080/00332925.2021.2044173.

- ^ "One Mystical Psychedelic Trip Can Trigger Lifelong Benefits | Psychology Today".

- ^ Ernst Zinner, in Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel, Frankfurt, 18 March 1957.

- ^ Bruno Weber, "Ubi caelum terrae se coniungit: Ein altertümlicher Aufriß des Weltgebäudes von Camille Flammarion", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, pp. 381-408 (1973) online link Archived 2023-07-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Joseph Ashbrook, "Astronomical Scrapbook: About an Astronomical Woodcut," Sky & Telescope, 53 (5), pp. 356-407, May 1977.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1873). The Atmosphere. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 103.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1872). L'atmosphère: description des grands phénomènes de la Nature. Paris: Hachette. p. 138.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1865). Les mondes imaginaires et les mondes réels. Paris: Didier. p. 246.

- ^ Rosweyde, Heribert; Migne, Jacques-Paul (1860). De Vitis Patrum Liber Primus. Paris. p. 415.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The legend of St. Macarius may be read in English translation at Vitae Patrum Archived 2011-05-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1865). Les mondes imaginaires et les mondes réels. Paris: Didier. p. 328.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1872). Histoire du Ciel. Paris: Lahure. p. 299.

ciel terre épaules Flammarion.

- ^ de La Mothe Le Vayer, François (1662). Oeuvres de François de La Mothe Le Vayer, Volume 3. Paris. p. 777.

- ^ Estève, Pierre (1755). Histoire generale et particuliere de l'astronomie. Paris. p. 242.

- ^ Flammarion, Camille (1884). Les terres du ciel. Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion. p. 395.

- ^ Kurutz, Steven (28 October 2019). "The Joy of Kooky". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ David Sandison: Oxtoby's Rockers, Page 44 - Phaidon/Oxford, 1978

- ^ Lorebook, Spelljammer boxset 1989, "Foreword" by Jeff Grubb: "But if space functions normally, how (for example) do the constellations of Krynn move around without messing up other planets? Zeb Cook pulled out some medieval woodcuts showing a traveler passing through the spheres of the world to discover the sun and planets on tracks, and with that the idea of crystal shells was born. Each fantasy solar system could have its own placement and rules, while being a part of a larger whole."

- ^ de Carvalho, Olavo (1995). O Jardim das Aflições – De Epicuro à ressurreição de César: ensaio sobre o Materialismo e a Religião Civil (in Brazilian Portuguese) (ebook ed.). Campinas: Vide Editorial. pp. §20. ISBN 85-67394-53-8.

- ^ "Urknall, Weltall und das Leben - Harald Lesch und Josef M. Gaßner". Urknall, Weltall und das Leben. Archived from the original on 2018-01-07. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ^ "Cat Stevens, 1970-'71". Archived from the original on 2021-05-23. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

External links

[edit]- Georg Peez: "Zum Beispiel; Anonymer und undatierter Holzschnitt" Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. (in German)