Flags of Napoleonic Italy

The Flags of Napoleonic Italy were the green, white and red tricolour flags and banners in use in Italy during the Napoleonic era, which lasted from 1796 to 1814. During this period, on 7 January 1797, the green, white and red tricolour was officially adopted for the first time as a national flag by a sovereign Italian state, the Cispadane Republic.[1][2] This event is commemorated by the Tricolour Day.

The premises

[edit]The Italian tricolour, like other tricolour flags, is inspired by the French one, introduced by the revolution in the autumn of 1790 on French Navy warships,[3] and symbol of the renewal perpetrated by the origins of Jacobinism.[4][5]

The first documented trace of the use of Italian national colours is dated 21 August 1789. In the historical archives of the Republic of Genoa it is reported that eyewitnesses had seen some demonstrators pinned on their clothes hanging a red, white and green cockade on their clothes.[6]

History

[edit]The banner of Cherasco

[edit]

The oldest documented mention of the Italian tricolour flag is linked to the first descent of Napoleon in the Italian Peninsula. With the start of the first campaign in Italy, in many places the Jacobins of the peninsula rose up, contributing, together with the Italian soldiers framed in the Napoleonic army, to the French victories.[7][8]

This renewal was accepted by the Italians despite being linked to the conveniences of Napoleonic France, which had strong imperialist tendencies, because the new political situation was better than the previous one. The double-threaded link with France was in fact much more acceptable than in past centuries in absolutism.[9]

During the first campaign in Italy, Napoleon, under the command of the Army of Italy, conquered the states into which the Italian peninsula was divided by founding new republican state bodies inspired by French revolutionary ideals.[10] Between 1796 and 1799 were born, among others, the Piedmontese Republic, the Cispadane Republic, the Transpadane Republic, the Ligurian Republic, the Roman Republic, the Anconine Republic and the Parthenopean Republic.[10] Many of these republics had a short existence, but despite this, the length of time that they existed was more than enough to spread the French revolutionary ideals, including that of the self-determination of the people, which laid the foundations for the unification of Italy.[10]

The first territory to be conquered by Napoleon was Piedmont; in the historical archive of the Piedmontese municipality of Cherasco there is a document that proves, on 13 May 1796, on the occasion of the homonymous armistice between Napoleon and the Austrian-Piedmontese troops, with which Victor Emmanuel I of Piedmont-Sardinia ceded Nice and Savoy to France to end the war,[11] the first mention of the Italian flag, which refers to municipal banners hoisted on three towers in the historic centre.[12]

[...] a banner was raised, made up of three canvases of different colours, namely Red, White,

GreenBlue. [...].[13]— Document kept in the municipality of Cherasco

On the document, the term "green" was subsequently crossed out and replaced by "blue", the colour that forms — together with white and red — the French flag.[4]

The war flag of the Lombard Legion

[edit]Despite the various hypotheses on the origin of the Italian tricolour and the meaning of its colours, there is no certain and unequivocal evidence of its existence before the entry of the French into Milan, which took place on 14 May 1796. In France, due to the Revolution, the flag had passed from having a "dynastic" and "military" meaning, to having a "national" one, and this concept, still unknown in Italy, was transmitted by the French to the Italians.[14]

This explains both the initial indifference to the adoption of the new flag, which left few certain traces of its origin, and the fact that initially, instead of adopting their own flag, many cities had raised the French tricolour. The new conquest was not, as in ancient times, "jealous" of its colours but proud that they were put on display, these being the symbols of a conquering army and a victorious people.[15] It is to the French flag that the documents, at least until October 1796, refer when they use the term "tricolour".[15]

On 11 October 1796, Napoleon communicated to the Directory the birth of the Lombard Legion, a military unit constituted by the General Administration of Lombardy,[16][17] a government headed by the Transpadane Republic.[18] On this document, in reference to its war flag, which traced the French tricolor and which was proposed to Napoleon by the Milanese patriots,[19] it is reported that:[20]

[...] Here you will find the organization of the Lombard Legion: the national colours adopted are green, white and red. [...][21]

— Napoleon

In this regard, one of the pro-Napoleonic Milanese patriots, the lawyer Giovanni Battista Sacco, declared:[19]

[...] Already the tricolour banner that has long flattered us to make ourselves free is subject to reform: our national colour is part of it and in a certain way we are assured that the dawn bearer of our regeneration is here [...][22]

— Giovanni Battista Sacco

The Lombard Legion was therefore the first Italian military unit to have a tricolour war flag as a banner.[18] According to the most authoritative sources, the choice made by the members of the Lombard Legion to replace the blue of the French flag with green is also linked to the colour of the uniforms of the Milanese city militia, whose members, since 1782, wore a uniform of this shade, that is a green outfit with red and white gorget patches. This is the reason, in the Milanese dialect, the members of this municipal guard were popularly called remolazzit, or "small radishes", recalling the luxuriant green leaves of this vegetable.[23]

The white and red were also peculiar to the very ancient municipal coat of arms of Milan and were also common on the Lombard military uniforms of the time.[5][23][24] It was therefore no coincidence that the green, white and red tricolour was chosen as an insignia by the Lombard Legion.[5]

The first official approval of the Italian flag by the authorities was as a military insignia of the Lombard Legion and not yet as the national flag of a sovereign Italian state.[25] On November 6, 1796, the first cohort of the Lombard Legion received its tricolour banner during a solemn ceremony at five o'clock in the afternoon in Piazza del Duomo in Milan.[26][20][24] The flag was divided into three vertical bands; it also reported the inscription "Lombard Legion" and the cohort number, while in the centre there was an oak crown that enclosed a Phrygian cap and a Masonic square with pendulum.[27] As shown in the "Prospectus of the formation of the Lombard Legion", each cohort was equipped with:[28]

[...] its Lombard national tricolour banner, distinguished by number and adorned with the emblems of freedom [...][29]

— Prospectus of the formation of the Lombard Legion

Flags of the same style were also assigned to the other five established cohorts.[16] All six banners are still extant, five being exhibited at the Museum of Military History in Vienna and one at the Musée de l'Armée in Paris.[20][30] With the succession of Napoleon's military victories and the consequent birth of republics favourable to revolutionary ideals, in many Italian cities, red, white and green were adopted on military banners as a symbol of social and political innovation.[31]

The war flag of the Italian Legion

[edit]From 16 to 18 October 1796, in Modena, a congress was held in which the delegates of Bologna, Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia participated, which decreed the birth of the Cispadane Republic, with lawyer Antonio Aldini as president.

The congress also deliberated the constitution of an Italian Legion, later renamed Cispadane Legion,[32] which was to participate together with France in a war against the Austrians. The military banner of this military unit, which consisted of five cohorts of six hundred soldiers each, was composed of a red, white and green tricolour, probably inspired by the similar decision of the Lombard Legion:[19][20][17]

[...] The constitution of the Cispadane Confederation is decreed, and the formation of the Italian Legion, whose cohorts must have as their flag the white, red and green banner adorned with the emblems of freedom. [...] [...] ART.VIII Each Cohort will have its flag in three Italian National colours, distinguished by number, and adorned with the emblems of Liberty. The numbers of the Cohorts will be drawn by lot among those formed by the four Provinces. [...][33]

— Constitution decree of the Italian Legion

Not yet a national flag, but a war flag,[27] the uniform of the soldiers of the Italian Legion was of the colours "already admitted by our Lombard brothers".[20]

The civic banner of the congregation of Bologna

[edit]On 19 June 1796, Bologna was occupied by Napoleonic troops.[30] At the same time, a Civic Guard was established, which adopted a uniform identical to that of the Milanese city militia, that is a green outfit with red and white displays.[30] On 18 October 1796,[24] at the same time as the constitution of the Italian Legion, the pro-Napoleonic congregation of magistrates and deputy deputies of Bologna, on the third point of the discussion, decided to create a tricolour civic banner, this time detached from military use. A document preserved in the Bologna State Archives states:[24]

[...] Flag with National Colours - Asked what the National colours are to form a Flag, Green, White and Red were answered [...][34]

— Resolution of the congregation of Bologna

A resolution of the Senate of Bologna of 5 November 1796 abolished "all those badges that characterize a diversity of ranks among citizens" while prescribing that "everyone must be provided within the term of eight days and wear the French tricolour cockade or also our mixed national colours".[35]

After the adoption by the Bolognese congregation, the tricolour became a political symbol of the struggle for the independence of Italy from foreign powers, given its use also in the civil sphere, taking the name of "flag of the Italian revolution".[24]

The subsequent adoption of the Italian flag by a state body, the Cispadane Republic, was inspired by this Bolognese banner, linked to a municipal reality and therefore still having a purely local breath, and to previous military banners of the Lombard and Italian Legions. which took place on January 7, 1797.[5][36]

The national flag of the Cispadane Republic

[edit]The premises

[edit]

With the invasion of Napoleon's troops, the Duke of Modena and Reggio Francesco III d'Este fled and the Reggian Republic was proclaimed (26 August 1796).[37] At the same time the Civic Guard of the city of Reggio was constituted and this military formation, aided by a small group of French grenadiers, defeated a squad of 150 Austrian soldiers at Montechiarugolo on 4 October 1796.[37] The victory was important — both from a political and symbolic point of view — that Napoleon made an official commendation to the Reggio soldiers who were the protagonists of the battle.[38] For the armed clash of Montechiarugolo, Napoleon defined the city of Reggio Emilia as:[39]

[...] "[Reggio Emilia is] the most mature Italian city for freedom" [...][40]

— Napoleon

Ugo Foscolo dedicated the ode A Bonaparte liberatore ("To Bonaparte Liberator") to the Reggio protagonists of the battle of Montechiarugolo.[41] The title page of this poem reads:[41][42]

To you, the first true Italians, free citizens you showed yourselves, and with magnanimous example you shook the already sleepy Italy, I dedicate to you, which belongs to you, this Oda which I on a free zither I dared to dissolve to our Liberator. Young, as I am, born in Greece, educated among Dalmatians, and stammering for only four years in Italy, neither where nor could he sing to free men and Italians. But the high genius of Liberty which inflames me, and which makes me a Free Man, and a Citizen of a homeland not by fate but chosen, gives me the rights of the Italian and lends me republican energy, so that I raised myself on myself. I sing Bonaparte Liberatore, and I dedicate my songs to the animating city of Italy[43]

— Ugo Foscolo

Vincenzo Monti dedicated these verses from his cantica In morte di Lorenzo Mascheroni ("On the death of Lorenzo Mascheroni") to the event:[41]

[...] Reggio still does not forget that from its bosom / the spark broke out whence the lightning / of our freedom ran [...][44]

— Vincenzo Monti

Moreover, in Reggio Emilia, in August 1796, one of the first liberty pole had been planted.[39] This event, which arose from a revolt against the ducal government on 20 August 1796 in Reggio, contributed, together with the events linked to the battle of Montechiarugolo, to the decision to choose Reggio Emilia as the venue for the cispadane congress, the assembly that then led to the birth of the flag of Italy.[39]

As a symbolic recognition of the Montechiarugolo clash, and for the event related to the tree of liberty, Napoleon suggested to the deputies of the Cispadan cities (Reggio, Modena, Bologna and Ferrara) to gather for their first congress assembly on 27 December 1796 in Reggio Emilia.[45]

The congresses of the Cispadane Republic and the adoption of the tricolour

[edit]

The proposal was followed despite controversy with the other cities of Emilia, which wanted the assembly organized in their own municipality;[39] the congress of 27 December took place then in the Reggio town hall designed by Bolognini which was to house the archive of the former duchy.[46] Here, 110 delegates chaired by Carlo Facci approved the constitutional charter of the Cispadane Republic, including the territories of Bologna, Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia.[47][48] For this reason the salon of the Bolognini was renamed "centumvirate congress hall" or "patriotic hall".[46]

In another session, dated 30 December 1796, the congress had approved a motion, amidst shower of applause such was the fervor of the delegates, which read:[49]

[...] Bologna, Ferrara, Modena and Reggio constitute a one and indivisible Republic for all relations, so that the four populations form only one people, one family, for all purposes, both past and future, no one except. [...][50]

— Minutes of the meeting of 30 December 1797 of the congress of the Cispadane Republic

In subsequent meetings, which always took place in the "hall of the congress centumvirate" of Reggio, many decisions were decreed and formalized, including the choice of the emblem of the newly formed republic.[51] To put forward the proposal for the adoption of a green, white and red national flag was Giuseppe Compagnoni, who for this reason is remembered as the "father of the Italian flag", in the XIV session of the cispadane congress[52] of 7 January 1797.[51][27][53] The adoption decree states:[52][54][55]

[...] From the minutes of the XIV Session of the Cispadan Congress: Reggio Emilia, 7 January 1797, 11 am. Patriotic Hall. The participants are 100, deputies of the populations of Bologna, Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia. Giuseppe Compagnoni also motioned that the standard or Cispadan Flag of three colours, Green, White and Red, should be rendered Universal and that these three colours should also be used in the Cispadan Cockade, which should be worn by everyone. It is decreed. [...][56]

— Decree of adoption of the tricolour flag by the Cispadane Republic

The final choice of a green, white and red flag was not without a prior discussion. Instead of the green, the Italian Jacobins favoured the blue of the French flag, while the members of the papacy preferred the yellow of the Papal States' banner. Regarding the white and red, there were no disputes.[24] Finally, the discussion on the third colour focused on green, which was later approved as a compromise solution.[24] The choice of green was most probably inspired by the tricolour green, white and red military flag of the Lombard Legion, the first Italian military department to equip itself, as a banner, with an Italian tricolour flag.[19]

The congress's decision to adopt a green, white and red tricolour flag was then also greeted by a jubilant atmosphere, enthusiasm of the delegates, and by bursts of applause.[23] For the first time, the city of ducal states for centuries enemies, they identify themselves as one people and a common identity symbol: the tricolour flag.[24]

The historic session of the congress did not specify the characteristics of this flag with the determination of the tonality and proportion of the colours, and did not even specify their location on the banner.[57] Also in the minutes of the meeting of Saturday 7 January 1797[24] read:[1]

[...] Always Compagnoni makes a motion that the coat of arms of the Republic be raised in all those places where it is customary to keep the coat of arms of the Sovereignty. [...] It also makes a motion that the Cispadane Standard or Flag of three colours, Green, White and Red, be made Universal and that these three colours are also used in the Cispadane Cockade, which must be worn by everyone. [...] Behind another motion by Compagnoni after some discussion, it is decreed that the Era of the Cispadane Republic begins on the first day of January of the current year 1797, and that this is called Year I of the Cispadan Republic to be marked in all public acts, adding, if you like, the year of the Common Era. It is decreed. [...][58]

— Minutes of the meeting of 7 January 1797 of the congress of the Cispadane Republic[24]

Events subsequent to the adoption of the flag

[edit]

For the first time the Italian flag officially became the national flag of a sovereign state, disengaging itself from the local military and civic meaning. This adoption of the Italian flag assumed an important political value.[1][2] On the basis of this event, the "centumvirate congress hall" of Reggio was later renamed "Sala del Tricolore".[46] In the assembly of 21 January, which was instead convened in Modena, the adoption of the Tricolour was confirmed:

[...] confirming the resolutions of previous meetings - decreed the flag of the State - by virtue of men and times - made a symbol of the indissoluble unity of the nation. [...][59]

— Minutes of the meeting of 21 January 1797 of the congress of the Cispadane Republic

The flag of the Cispadane Republic was in horizontal bands with the top red, the white in the centre and the green at the bottom. In the centre was also the emblem of the republic, while on the sides the letters "R" and "C" were shown, the initials of the two words that form the name of the "Repubblica Cispadana".[27] The coat of arms of the Cispadane Republic contained a quiver with four arrows that symbolized the four cities of the Cispadan congress.[45]

The Italian flag was first displayed in public in Modena on February 12, 1797; to celebrate the event a procession was organized through the streets of the city, which went down in history with the name of "patriotic walk",[52] with exponents of the civic guard and the army who solemnly honoured it.[57] From this date, the Italian tricolour also spread beyond the borders of Emilia, especially in Lombardy, and began to be used more and more often as a military banner by the Napoleonic soldiers who fought in Italy.[57]

In Bergamo, civilians were obliged to wear a tricolour cockade pinned to their clothes, a coercion that was sanctioned, on 13 May 1797, also in Modena and Reggio nell'Emilia.[60][61] Even without the need for obligations on the part of the authorities, the cockade spread more and more among the population, who wore it with pride, laying the foundations, together with other factors, for the Risorgimento.[62]

The green, white and red tricolour was then adopted by the cities of Venice, Brescia, Padua, Bergamo, Vicenza and Verona,[63] with the latter having rebelled against the government of the Republic of Venice.[52]

The national flag of the Cisalpine Republic

[edit]

A few months later, on 29 June 1797, with the union between the Cispadane and Transpadane republics, the Cisalpine Republic was formed, a large-scale pro-Napoleonic state body with Milan as its capital.[9][64]

At the formal celebration of the birth in the new republic, which took place on 9 July in the Milanese capital, 300,000 people participated (only 25,000 according to other sources[63]), including ordinary citizens, French soldiers and representatives of the major municipalities of the republic.[9] According to Francesco Melzi d'Eril, a participant of the event, there were about 1,000 Milanese citizens who spontaneously participated in the celebration, while the remaining part was made up of soldiers.[63]

The event, which took place at the lazaretto of Milan, was characterized by a riot of flags and tricolour cockades.[65] On this occasion Napoleon solemnly gave to the military units of the newborn republic, after having reviewed them, their tricolour banners.[63]

Originally the colours of the flag of the Cisalpine Republic were arranged horizontally, with green at the top,[65] but on 11 May 1798, the Grand Council of the newborn State chose, as the national banner, an Italian tricolour with the colours arranged vertically:[27][66][67]

[...] the Flag of the Cisalpine Nation is made up of three bands parallel to the shaft, green, the next white, the third red. The shaft is similarly tri-coloured in a spiral, with a white tip [...][68]

— Resolution of the Grand Council of the Cisalpine Republic

The sedentary National Guard of the Cisalpine Republic was structured similarly to the Lombard and Cispadana Legions, that is, into legions, battalions and companies.[69] The uniform of this military team was white, red and green:[69]

[...] [The soldiers will wear] cockade and plume in the national colours. [...] [Furthermore] each battalion will have a flag with the three national colours, in the bottom of which will be written on one side the Cisalpine National Guard, with the name of the department, the legion number, and of the battalion: on the other "freedom", "equality", "support for the laws". [...][70]

— Organization and regulations for the National Guard of the Cisalpine Republic

The Cisalpine Republic, since it included Lombardy, part of the Veronese area, the former Duchy of Modena and Reggio, the former Duchy of Massa and Carrara, the Legations of Bologna, Ferrara and Romagna, was the nucleus of modern Italy,[67] despite Napoleon having ceded to Archduchy of Austria, with the Treaty of Campo Formio (17 October 1797), the territories of the former Republic of Venice, namely Veneto, Friuli, Istria, Dalmatia, control over the Republic of Ragusa, until that moment in the orbit of the Venice of the Doges.[71]

The first Cisalpine Republic lasted until 1799, when it was occupied and dissolved by the Austrians and the Russians, or by two of the armies that were part of the Second Coalition.[72] In 1800, Napoleon again invaded Italy from Egypt, succeeding in reconquering the territories previously subtracted from the second coalition and reviving, among other things, the Cisalpine Republic.[73] On this occasion Napoleon decreed the use of the tricolour for the National Guards of each city.[73] A proclamation of 20 September 1800 confirmed the colours of the national cockade, white, red and green, specifying that it had to be affixed to clothing in such a way as to be clearly visible.[73] In this context the Subalpine Republic was born, a pro-Napoleonic state body that replaced the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia. The Subalpine Republic also had a short life, given that on 11 September 1802 it was annexed to the French First Republic.[74][75]

In this period was born the attachment of the population towards the Italian flag, which began to enter the social imaginary as a symbol of the country.[76] This popular notoriety was however limited to Northern Italy; other pro-Napoleonic state bodies had in fact adopted other banners. The Roman Republic, for example, a black, white and red national flag, the Parthenopean Republic had, as a national banner, a blue, yellow and red flag,[77] while the Anconine Republic was represented by a blue, yellow and red banner.[67]

This was especially true in the army, where the tricolour military banner was defended at all costs from the capture of the enemy. An episode that occurred on 16 January 1801, during the second Cisalpine Republic[78] was significant in that the Napoleonic officer Teodoro Lechi, in a clash with the Austrians in Trento during which a bridge over the Adige river was disputed, decided to burn the tricolour flags of the military unit to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy before surrendering.[76]

The national flags of the Italian Republic and of the Kingdom of Italy

[edit]

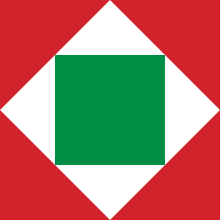

With the transformation of the Cisalpine Republic into the Italian Republic (1802–1805), a state body that did not include the entire Italian peninsula and which was also directly dependent on Napoleonic France, the arrangement of the colours on the flag changed into a composition formed by a green square inserted in a white diamond,[79] in turn included in a red box. The Presidential standard of Italy in use since 14 October 2000[80][81] was inspired by this flag.

The radical change in the arrangement of the colours was probably proposed by the Vice President of the Republic Francesco Melzi d'Eril, who perhaps wanted to communicate, even from a symbolic point of view, the end of a phase of the history of Italy.[52] The decree of adoption of the historic Napoleonic flag, which is dated 20 August 1802, reads:[82]

[...] [the flag of the Italian Republic is formed by] a square with a red background, in which a rhombus with a white background is inserted, containing another square with a green background [...][83]

— Decree of adoption of the flag of the Napoleonic Italian Republic

Melzi d'Eril also wanted to eliminate the green but, due to the opposition of Napoleon and the "pressure of democratic Masonic moral forces,[84] the colour was kept.[85]

With the transformation of the Italian Republic into the Kingdom of Italy (1805–1814), also a state body not including the entire Italian peninsula, the flag did not undergo substantial changes.[85] In the meantime, the Napoleonic revolutionary thrust underwent an evolution, taking on more reactionary hues: for example, the French revolutionary calendar was abolished, which was replaced by the restoration of the ancient Gregorian calendar, and many myths of the French revolution, such as the Storming of the Bastille, were overshadowed.[86]

This change also affected the use of flags and cockades. The Italian tricolour was increasingly replaced by the French one, with the blue of the French flag taking the place of the green of the Italian banner.[79] This change was also formal: the bands of mayors now consisted of the French tricolour and no longer the Italian one.[79]

Despite these limitations, the green, white and red tricolour continued to enter more and more into the collective imagination of Italians becoming, to all intents and purposes, an unequivocal symbol of Italianness.[77][87] In just under 20 years, the Italian flag, from a simple banner derived from the French one, had acquired its own identity, becoming very famous and well known.[87]

Aftermath

[edit]

With the fall of Napoleon (1814) and the restoration of the absolutist monarchical regimes, the Italian tricolour went underground, becoming the symbol of the patriotic ferments that began to spread in Italy[19][87] and the symbol which united all the efforts of the Italian people towards freedom and independence.[88]

Between 1820 and 1861, a sequence of events led to the independence and unification of Italy (except for Veneto and the province of Mantua, Lazio, Trentino-Alto Adige and Julian March, known as Italia irredenta, which were united with the rest of Italy in 1866 after the Third Italian War of Independence, in 1870 after the capture of Rome, and in 1918 after the First World War respectively); this period of Italian history is known as the Risorgimento. The Italian tricolour waved for the first time in the history of the Risorgimento on 11 March 1821 in the Cittadella of Alessandria, during the revolutions of 1820s, after the oblivion caused by the restoration of the absolutist monarchical regimes.[89]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Busico 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b Maiorino 2002, p. 155.

- ^ "Le drapeau français – Présidence de la République" (in French). Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Otto mesi prima di Reggio il tricolore era già una realtà" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d "I simboli della Repubblica" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna Storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 662. Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Tarozzi 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Tarozzi 1999, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Maiorino 2002, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Busico 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Bazzano 2011, p. 130.

- ^ Giovanni Francesco Damilano, Libro familiare di me sacerdote ed avvocato Giovanni Francesco Damilano 1775–1802, Cherasco, Fondo Adriani, Historical Archive of the City of Cherasco, 1803, p. 36. (in Italian)

- ^ [...] si è elevato uno stendardo, formato con tre tele di diverso colore, cioè Rosso, Bianco,

VerdeBleu. [...] - ^ Fiorini 1897, p. 685.

- ^ a b Fiorini 1897, p. 688.

- ^ a b Bovio 1996, p. 19.

- ^ a b Tarozzi 1999, p. 68.

- ^ a b "L'Esercito del primo Tricolore" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Villa 2010, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Busico 2005, p. 11.

- ^ [...] Qui troverete l'organizzazione della Legione Lombarda: i colori nazionali adottati sono il verde, il bianco e il rosso. [...]

- ^ [...] Già il tricolore vessillo che da gran tempo ci lusinga di renderci liberi soggiace a riforma: il color nostro nazionale vi ha parte e in certo modo ci si assicura che presso è a spuntare l'aurora apportatrice della nostra rigenerazione [...]

- ^ a b c Maiorino 2002, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Villa 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Tarozzi 1999, p. 67-68.

- ^ Tarozzi 1999, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Vecchio 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 44.

- ^ [...] suo stendardo tricolorato nazionale lombardo, distinto per numero ed ornato degli emblemi della libertà [...]

- ^ a b c Colangeli 1965, p. 14.

- ^ Maiorino 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Frasca, Francesco (19 March 2009). Reclutamento e guerra nell'Italia napoleonica (in Italian). ISBN 9781409260899. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ [...] Si decreta la costituzione della Confederazione Cispadana, e la formazione della Legione Italiana, le cui coorti debbono avere come bandiera il vessillo bianco, rosso e verde adorna degli emblemi della libertà. [...] [...] ART.VIII Ogni Coorte avrà la sua bandiera a tre colori Nazionali Italiani, distinte per numero, e adorne degli emblemi della Libertà. I numeri delle Coorti saranno estratti a sorte fra quelle formate delle quattro Provincie. [...]

- ^ [...] Bandiera coi colori Nazionali – Richiesto quali siano i colori Nazionali per formarne una Bandiera, si è risposto il Verde il Bianco ed il Rosso [...]

- ^ Fiorini 1897, pp. 703–704.

- ^ "Bologna, 28 ottobre 1796: Nascita della Bandiera Nazionale Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ a b Busico 2005, p. 209.

- ^ Busico 2005, pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b c d Villa 2010, p. 45.

- ^ [...] la città italiana più matura per la libertà [...]

- ^ a b c "Il tricolore è più bello col sole" (in Italian). Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "Ugo Foscolo - Appendice - Poesie giovanili" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ A voi, che primi veri italiani, liberi cittadini vi siete mostrati, e con esempio magnanimo scuoteste l'Italia già sonnacchiosa, a voi dedico, che a voi spetta, quest'Oda ch'io su libera cetra osai sciogliere al nostro Liberatore. Giovane, qual mi son io, nato in Grecia, educato fra Dalmati, e balbettante da soli quattr'anni in Italia, né dovea, né poteva cantare ad uomini liberi ed Italiani. Ma l'alto genio di Libertà che m’infiamma, e che mi rende Uomo Libero, e Cittadino di patria non in sorte toccata ma eletta, mi dà i diritti dell'Italiano e mi presta repubblicana energia, ond'io alzato su me medesimo canto Bonaparte Liberatore, e consacro i miei Canti alla città animatrice d'Italia.

- ^ [...] Reggio ancor non oblia che dal suo seno / la favilla scoppiò donde primiero / di nostra libertà corse il baleno [...]

- ^ a b Busico 2005, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Busico 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Maiorino 2002, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Fiorini 1897, pp. 704–705.

- ^ Fiorini 1897, p. 705.

- ^ [...] Bologna, Ferrara, Modena e Reggio costituiscono una Repubblica una e indivisibile per tutti i rapporti, dimodoché le quattro popolazioni non formino che un popolo solo, una sola famiglia, per tutti gli effetti, tanto passati, quanto futuri, niuno eccettuato [...]

- ^ a b Maiorino 2002, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e "Origini della bandiera tricolore italiana" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Tarozzi 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Fiorini 1897, p. 706.

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 46.

- ^ [...] Dal verbale della Sessione XIV del Congresso Cispadano: Reggio Emilia, 7 gennaio 1797, ore 11. Sala Patriottica. Gli intervenuti sono 100, deputati delle popolazioni di Bologna, Ferrara, Modena e Reggio Emilia. Giuseppe Compagnoni fa pure mozione che si renda Universale lo Stendardo o Bandiera Cispadana di tre colori, Verde, Bianco e Rosso e che questi tre colori si usino anche nella Coccarda Cispadana, la quale debba portarsi da tutti. Viene decretato. [...]

- ^ a b c Maiorino 2002, p. 159.

- ^ [...] Sempre Compagnoni fa mozione che lo stemma della Repubblica sia innalzato in tutti quei luoghi nei quali è solito che si tenga lo Stemma della Sovranità. [...] Fa pure mozione che si renda Universale lo Stendardo o Bandiera Cispadana di tre colori, Verde, Bianco e Rosso e che questi tre colori si usino anche nella Coccarda Cispadana, la quale debba portarsi da tutti. [...] Dietro ad altra mozione di Compagnoni dopo qualche discussione, si decreta che l'Era della Repubblica Cispadana incominci dal primo giorno di gennaio del corrente anno 1797, e che questo si chiami Anno I della Repubblica Cispadana da segnarsi in tutti gli atti pubblici, aggiungendo, se si vuole, l'anno dell'Era volgare. Vien decretato. [...]

- ^ [...] confermando le delibere di precedenti adunanze – decretò vessillo di Stato il Tricolore – per virtù d'uomini e di tempi – fatto simbolo dell'unità indissolubile della Nazione. [...]

- ^ Villa 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Maiorino 2002, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Maiorino 2002, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d Villa 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Villa 2010, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Maiorino 2002, p. 163.

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Busico 2005, p. 17.

- ^ [...] la Bandiera della Nazione Cisalpina è formata di tre bande parallele all'asta, verde, la successiva bianca, la terza rossa. L'Asta è similmente tricolorata a spirale, colla punta bianca [...]

- ^ a b Busico 2005, p. 15.

- ^ [...] [I soldati porteranno] coccarda e pennacchio coi colori nazionali. [...] [Inoltre] ciascun battaglione avrà una bandiera con i tre colori nazionali, nel fondo del quale sarà scritto da una parte Guardia Nazionale Cisalpina, col nome del dipartimento, il numero di legione, e del battaglione: dall'altra "libertà", "eguaglianza", "sostegno delle leggi" [...]

- ^ Busico 2005, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Busico 2005, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Villa 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 21.

- ^ "Repubblica Subalpina" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Maiorino 2002, p. 166.

- ^ a b Villa 2010, p. 15.

- ^ A. A. V. V (23 July 2009). Armi e nazione. Dalla Repubblica Cisalpina al Regno d'Italia (1797-1814) (in Italian). ISBN 9788856809985. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Maiorino 2002, p. 168.

- ^ "Lo Stendardo presidenziale" (in Italian). Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Romano, Antonio (30 April 2013). Tutte le auto dei presidenti. Storie di ammiraglie, limousine ed esemplari unici utilizzati per scopi «presidenziali» rigorosamente made in Italy (in Italian). ISBN 9788849276268. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 16.

- ^ [...] [la bandiera della Repubblica Italiana è formata da] un quadrato a fondo rosso, in cui è inserito un rombo a fondo bianco, contenente un altro quadrato a fondo verde [...]

- ^ In fact, green is also the colour of Freemasonry.

- ^ a b Bovio 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Maiorino 2002, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Maiorino 2002, p. 169.

- ^ Ghisi, Enrico Il tricolore italiano (1796–1870) Milano: Anonima per l'Arte della Stampa, 1931; see Gay, H. Nelson in The American Historical Review Vol. 37 No. 4 (pp. 750–751), July 1932 JSTOR 1843352

- ^ Villa 2010, p. 18.

References

[edit]- Bazzano, Nicoletta (2011). Donna Italia. L'allegoria della Penisola dall'antichità ai giorni nostri. Angelo Colla Editore.

- Bovio, Oreste (1996). Due secoli di tricolore (in Italian). Ufficio storico dello Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito. SBN IT\ICCU\BVE\0116837.

- Busico, Augusta (2005). Il tricolore: il simbolo la storia (in Italian). Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Dipartimento per l'informazione e l'editoria. SBN IT\ICCU\UBO\2771748.

- Colangeli, Oronzo (1965). Simboli e bandiere nella storia del Risorgimento italiano (PDF) (in Italian). Patron. SBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0395583.

- Fiorini, Vittorio (1897). "Le origini del tricolore italiano". Nuova Antologia di Scienze Lettere e Arti (in Italian). LXVII (fourth series): 239–267 and 676–710. SBN IT\ICCU\UBO\3928254.

- Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2.

- Tarozzi, Fiorenza; Vecchio, Giorgio (1999). Gli italiani e il tricolore (in Italian). Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-07163-6.

- Vecchio, Giorgio (2003). "Il tricolore". Almanacco della Repubblica (in Italian). Bruno Mondadori. pp. 42–55. ISBN 88-424-9499-2.

- Villa, Claudio (2010). I simboli della Repubblica: la bandiera tricolore, il canto degli italiani, l'emblema (in Italian). Comune di Vanzago. SBN IT\ICCU\LO1\1355389.