Fixed-wing aircraft: Difference between revisions

Arpingstone (talk | contribs) Wrong use of capitals |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

A '''fixed-wing aircraft''', usually called an '''aeroplane''' or '''airplane''', is a heavier-than-air [[aircraft]] capable of [[flight]] whose [[Lift (force)|lift]] is generated not by wing motion relative to the aircraft, but by forward motion through the air. The term is used to distinguish fixed-wing aircraft from [[rotary-wing aircraft]] and [[ornithopters]] in which lift is generated by [[Helicopter rotor#Blade design|blades]] or wings that move relative to the [[aircraft]]. Many fixed-wing aircraft are propelled forward by the [[thrust]] from [[propeller]]s or [[jet engine]]s, but the category includes unpowered aircraft (usually called [[glider]]s). |

A '''fixed-wing aircraft''', usually called an '''aeroplane''' or '''airplane''', is a heavier-than-air [[aircraft]] capable of [[flight]] whose [[Lift (force)|lift]] is generated not by wing motion relative to the aircraft, but by forward motion through the air. The term is used to distinguish fixed-wing aircraft from [[rotary-wing aircraft]] and [[ornithopters]] in which lift is generated by [[Helicopter rotor#Blade design|blades]] or wings that move relative to the [[aircraft]]. Many fixed-wing aircraft are propelled forward by the [[thrust]] from [[propeller]]s or [[jet engine]]s, but the category includes unpowered aircraft (usually called [[glider]]s). |

||

In the United States, Canada and many other regions, the term "airplane" is applied to these aircraft. In Britain and many other regions, the term "aeroplane" is used. The word derives from the Greek ''αέρας'' (aéras-) ("air") and ''[[Plane (mathematics)|-plane]]''.<ref>"Aeroplane", [[Oxford English Dictionary]], ''Second edition, 1989.''</ref> The form "aeroplane" is the older of the two, dating back to the mid-late 19th century.<ref>[[Lawrence Hargrave]] was one of the aviators to use the term "'''aeroplane'''" from an early date. [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9A01EFD8163BEE33A25750C0A9679C94639ED7CF "Is the air ship found?"] New York Times, January 3, 1892.</ref> The spelling "airplane" was first recorded in 1907.<ref> |

In the United States, Canada and many other regions, the term "airplane" is applied to these aircraft. In Britain and many other regions, the term "aeroplane" is used. The word derives from the Greek ''αέρας'' (aéras-) ("air") and ''[[Plane (mathematics)|-plane]]''.<ref>"Aeroplane", [[Oxford English Dictionary]], ''Second edition, 1989.''</ref> The form "aeroplane" is the older of the two, dating back to the mid-late 19th century.<ref>[[Lawrence Hargrave]] was one of the aviators to use the term "'''aeroplane'''" from an early date. [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9A01EFD8163BEE33A25750C0A9679C94639ED7CF "Is the air ship found?"] New York Times, January 3, 1892.</ref> The spelling "airplane" was first recorded in 1907.<ref>Merriamirplane</ref> |

||

Most fixed-wing aircraft are flown by a pilot on-board the aircraft, but some are designed to be [[unmanned aerial vehicle|remotely or robot controlled]]. |

Most fixed-wing aircraft are flown by a pilot on-board the aircraft, but some are designed to be [[unmanned aerial vehicle|remotely or robot controlled]]. |

||

Revision as of 18:40, 8 June 2009

| Fixed-wing aircraft | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Boeing 737-300, a modern passenger airliner | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Supported by LTA gases + aerodynamic lift | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Supported by aerodynamic lift (aerodynes) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Other means of lift | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

A fixed-wing aircraft, usually called an aeroplane or airplane, is a heavier-than-air aircraft capable of flight whose lift is generated not by wing motion relative to the aircraft, but by forward motion through the air. The term is used to distinguish fixed-wing aircraft from rotary-wing aircraft and ornithopters in which lift is generated by blades or wings that move relative to the aircraft. Many fixed-wing aircraft are propelled forward by the thrust from propellers or jet engines, but the category includes unpowered aircraft (usually called gliders).

In the United States, Canada and many other regions, the term "airplane" is applied to these aircraft. In Britain and many other regions, the term "aeroplane" is used. The word derives from the Greek αέρας (aéras-) ("air") and -plane.[1] The form "aeroplane" is the older of the two, dating back to the mid-late 19th century.[2] The spelling "airplane" was first recorded in 1907.[3]

Most fixed-wing aircraft are flown by a pilot on-board the aircraft, but some are designed to be remotely or robot controlled.

Structure

The structure of a fixed-wing aircraft consists of the following major parts:

- A long narrow often cylindrical form, called a fuselage, usually with tapered or rounded ends to make its shape aerodynamically smooth. The fuselage carries the human flight crew if the aircraft is piloted, the passengers if the aircraft is a passenger aircraft, other cargo or payload, and engines and/or fuel if the aircraft is so equipped. The pilots operate the aircraft from a cockpit located at the front or top of the fuselage and equipped with windows, controls, and instruments. Passengers and cargo occupy the remaining available space in the fuselage. Some aircraft may have two fuselages, or additional pods or booms.

- A wing (or wings in a multiplane) with an airfoil cross-section shape, used to generate aerodynamic lifting force to support the aircraft in flight by deflecting air downward as the aircraft moves forward. The wing halves are typically symmetrical about the plane of symmetry (for symmetrical aircraft). The wing also stabilizes the aircraft about its roll axis and the ailerons control rotation about that axis.

- At least one control surface (or surfaces) mounted vertically usually above the rear of the fuselage, called a vertical stabilizer. The vertical stabilizer is used to stabilize the aircraft about its yaw axis (the axis in which the aircraft turns from side to side) and to control its rotation along that axis. Some aircraft have multiple vertical stabilizers.

- At least one horizontal surface at the front or back of the fuselage used to stabilize the aircraft about its pitch axis (the axis around which the aircraft tilts upward or downward). The horizontal stabilizer (also known as tailplane) is usually mounted near the rear of the fuselage, or at the top of the vertical stabilizer, or sometimes a canard is mounted near the front of the fuselage for the same purpose.

- On powered aircraft, one or more aircraft engines are propulsion units that provide thrust to push the aircraft forward through the air. The engine is optional in the case of gliders that are not motor gliders. The most common propulsion units are propellers, powered by reciprocating or turbine engines, and jet engines, which provide thrust directly from the engine and usually also from a large fan mounted within the engine. When the number of engines is even, they are distributed symmetrically about the roll axis of the aircraft, which lies along the plane of symmetry (for symmetrical aircraft); when the number is odd, the odd engine is usually mounted along the centerline of the fuselage.

- Landing gear, a set of wheels, skids, or floats that support the aircraft while it is on the surface.

Some varieties of aircraft, such as flying wing aircraft, may lack a discernible fuselage structure and horizontal or vertical stabilizers.

Controls

A number of controls allow pilots to direct aircraft in the air. The controls found in a typical fixed-wing aircraft are as follows:

- A yoke or joystick, which controls rotation of the aircraft about the pitch and roll axes. A yoke resembles a kind of steering wheel, and a control stick is just a simple rod with a handgrip. The pilot can pitch the aircraft downward by pushing on the yoke or stick, and pitch the aircraft upward by pulling on it. Rolling the aircraft is accomplished by turning the yoke in the direction of the desired roll, or by tilting the control stick in that direction. Pitch changes are used to adjust the altitude and speed of the aircraft; roll changes are used to make the aircraft turn. Control sticks and yokes are usually positioned between the pilot's legs; however, a sidestick is a type of control stick that is positioned on either side of the pilot (usually the left side for the pilot in the left seat, and vice versa, if there are two pilot seats).

- Rudder pedals, which control rotation of the aircraft about the yaw axis. There are two pedals that pivot so that when one is pressed forward the other moves backward, and vice versa. The pilot presses on the right rudder pedal to make the aircraft yaw to the right, and on the left pedal to make it yaw to the left. The rudder is used mainly to balance the aircraft in turns, or to compensate for winds or other effects that tend to turn the aircraft about the yaw axis.

- A throttle, which adjusts the thrust produced by the aircraft's engines. The pilot uses the throttle to increase or decrease the speed of the aircraft, and to adjust the aircraft's altitude (higher speeds cause the aircraft to climb, lower speeds cause it to descend). In some aircraft the throttle is a single lever that controls thrust; in others, adjusting the throttle means adjusting a number of different engine controls simultaneously. Aircraft with multiple engines usually have individual throttle controls for each engine.

- Brakes, used to slow and stop the aircraft on the ground, and sometimes for turns on the ground.

Other possible controls include:

- Flap levers, which are used to control the position of flaps on the wings.

- Spoiler levers, which are used to control the position of spoilers on the wings, and to arm their automatic deployment in aircraft designed to deploy them upon landing.

- Trim controls, which usually take the form of knobs or wheels and are used to adjust pitch, roll, or yaw trim.

- A tiller, a small wheel or lever used to steer the aircraft on the ground (in conjunction with or instead of the rudder pedals).

- A parking brake, used to prevent the aircraft from rolling when it is parked on the ground.

The controls may allow full or partial automation of flight, such as an autopilot, a wing leveler, or a flight management system. Pilots adjust these controls to select a specific attitude or mode of flight, and then the associated automation maintains that attitude or mode until the pilot disables the automation or changes the settings. In general, the larger and/or more complex the aircraft, the greater the amount of automation available to pilots.

Control duplication

On an aircraft with a pilot and copilot, or instructor and trainee, the aircraft is made capable of control without the crew changing seats. The most common arrangement is two complete sets of controls, one for each of two pilots sitting side by side, but in some aircraft (military fighter aircraft, some taildraggers and aerobatic aircraft) the dual sets of controls are arranged one in front of the other. A few of the less important controls may not be present in both positions, and one position is usually intended for the pilot in command (e.g., the left "captain's seat" in jet airliners). Some small aircraft use controls that can be moved from one position to another, such as a single yoke that can be swung into position in front of either the left-seat pilot or the right-seat pilot (i.e. Beechcraft Bonanza).

Aircraft that require more than one pilot usually have controls intended to suit each pilot position, but still with sufficient duplication so that all pilots can fly the aircraft alone in an emergency. For example, in jet airliners, the controls on the left (captain's) side include both the basic controls and those normally manipulated by the pilot in command, such as the tiller, whereas those of the right (first officer's) side include the basic controls again and those normally manipulated by the copilot, such as flap levers. The unduplicated controls that are required for flight are positioned so that they can be reached by either pilot, but they are often designed to be more convenient to the pilot who manipulates them under normal condition.

Aircraft instruments

Instruments provide information to the pilot. Flight instruments provide information about the aircraft's speed, direction, altitude, and orientation. Powerplant instruments provide information about the the status of the aircraft's engines and APU. Systems instruments provide information about the aircraft's other systems, such as fuel delivery, electrical, and pressurization. Navigation and communication instruments include all the aircraft's radios. Instruments may operate mechanically or electrically, requiring 12VDC, 24VDC, or 400 Hz power systems.[4] An aircraft that uses computerized CRT or LCD displays almost exclusively is said to have a glass cockpit.

Basic instruments include:

- An airspeed indicator, which indicates the speed at which the aircraft is moving through the surrounding air.

- An altimeter, which indicates the altitude of the aircraft above mean sea level.

- A Heading indicator, (sometimes referred to as a "directional gyro (DG)") which indicates the magnetic compass heading that the aircraft's fuselage is pointing towards. The actual direction the aircraft is flying towards is affected by the wind conditions.

- An attitude indicator, sometimes called an artificial horizon, which indicates the exact orientation of the aircraft about its pitch and roll axes.

Other instruments might include:

- A Turn coordinator, which helps the pilot maintain the aircraft in a coordinated attitude while turning.

- A rate-of-climb indicator, which shows the rate at which the aircraft is climbing or descending

- A horizontal situation indicator, shows the position and movement of the aircraft as seen from above with respect to the ground, including course/heading and other information.

- Instruments showing the status of each engine in the aircraft (operating speed, thrust, temperature, and other variables).

- Combined display systems such as primary flight displays or navigation displays.

- Information displays such as on-board weather radar displays.

Propulsion

Fixed-wing aircraft can be sub-divided according to the means of propulsion they use.

Unpowered aircraft

Aircraft that primarily intended for unpowered flight include gliders (sometimes called sailplanes), hang gliders and paragliders. These are mainly used for recreation. After launch, further energy is obtained through the skilful exploitation of rising air in the atmosphere. Gliders that are used for the sport of gliding have high aerodynamic efficiency. The highest lift-to-drag ratio is 70:1, though 50:1 is more common. Glider flights of thousands of kilometers at average speeds over 200 km/h have been achieved. The glider is most commonly launched by a tow-plane or by a winch. Some gliders, called motor gliders, are equipped with engines (often retractable) and some are capable of self-launching. The most numerous unpowered aircraft are hang gliders and paragliders. These are foot-launched and are generally slower, less massive, and less expensive than sailplanes. Hang gliders most often have flexible wings which are given shape by a frame, though some have rigid wings. This is in contrast to paragliders which have no frames in their wings. Military gliders have been used in war to deliver assault troops, and specialized gliders have been used in atmospheric and aerodynamic research. Experimental aircraft and winged spacecraft have also made unpowered landings.

Propeller aircraft

Smaller and older propeller aircraft make use of reciprocating internal combustion engines that turns a propeller to create thrust. They are quieter than jet aircraft, but they fly at lower speeds, and have lower load capacity compared to similar sized jet powered aircraft. However, they are significantly cheaper and much more economical than jets, and are generally the best option for people who need to transport a few passengers and/or small amounts of cargo. They are also the aircraft of choice for pilots who wish to own an aircraft.

Turboprop aircraft are a halfway point between propeller and jet: they use a turbine engine similar to a jet to turn propellers. These aircraft are popular with commuter and regional airlines, as they tend to be more economical on shorter journeys.

Jet aircraft

Jet aircraft make use of turbines for the creation of thrust. These engines are much more powerful than a reciprocating engine. As a consequence, they have greater weight capacity and fly faster than propeller driven aircraft. One drawback, however, is that they are noisy; this makes jet aircraft a source of noise pollution. However, turbofan jet engines are quieter, and they have seen widespread usage partly for that reason.

The jet aircraft was developed in Germany in 1931. The first jet was the Heinkel He 178, which was tested at Germany's Marienehe Airfield in 1939. In 1943 the Messerschmitt Me 262, the first jet fighter aircraft, went into service in the German Luftwaffe. In the early 1950s, only a few years after the first jet was produced in large numbers, the De Havilland Comet became the world's first jet airliner. However, the early Comets were beset by structural problems discovered after numerous pressurization and depressurization cycles, leading to extensive redesigns.

Most wide-body aircraft can carry hundreds of passengers and several tons of cargo, and are able to travel for distances up to 17,000 km. Aircraft in this category are the Boeing 747, Boeing 767, Boeing 777, the upcoming Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 , Airbus A300/A310, Airbus A330, Airbus A340, Airbus A380, Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, McDonnell Douglas DC-10, McDonnell Douglas MD-11, Ilyushin Il-86, and Ilyushin Il-96.

Jet aircraft possess high cruising speeds (700 to 900 km/h, or 400 to 550 mph) and high speeds for take-off and landing (150 to 250 km/h). Due to the speed needed for takeoff and landing, jet aircraft make use of flaps and leading edge devices for the control of lift and speed, as well as thrust reversers to direct the airflow forward, slowing down the aircraft upon landing.

Supersonic jet aircraft

Supersonic aircraft, such as military fighters and bombers, Concorde, and others, make use of turbines (often utilizing afterburners), that generate the huge amounts of power for flight faster than the speed of the sound. Flight at supersonic speed creates more noise than flight at subsonic speeds, due to the phenomenon of sonic booms. This limits supersonic flights to areas of low population density or open ocean. When approaching an area of heavier population density, supersonic aircraft are obliged to fly at subsonic speed.

Due to the high costs, limited areas of use and low demand there are no longer any supersonic aircraft in use by any major airline. The last Concorde flight was on 26 November 2003.

Solar-powered Aircraft

An solar-powered aircraft generates the needed energy by means of solarcells.

Unmanned Aircraft

An aircraft is said to be 'unmanned' when there is no person in the cockpit of the plane. The aircraft is controlled only by remote controls or other electronic devices.

Rocket-powered aircraft

Experimental rocket powered aircraft were developed by the Germans as early as World War II (see Me 163 Komet), and about 29 were manufactured and deployed. The first fixed wing aircraft to break the sound barrier in level flight was a rocket plane- the Bell X-1. The later North American X-15 was another important rocket plane that broke many speed and altitude records and laid much of the groundwork for later aircraft and spacecraft design. Rocket aircraft are not in common usage today, although rocket-assisted takeoffs are used for some military aircraft. SpaceShipOne is the most famous current rocket aircraft, being the testbed for developing a commercial sub-orbital passenger service; another rocket plane is the XCOR EZ-Rocket; and there is of course the Space Shuttle.

Ramjet aircraft

A ramjet is a form of jet engine that contains no major moving parts and can be particularly useful in applications requiring a small and simple engine for high speed use, such as missiles. The D-21 Tagboard was an unmanned Mach 3+ reconnaissance drone that was put into production in 1969 for spying, but due to the development of better spy satellites, it was cancelled in 1971. The SR-71's Pratt & Whitney J58 engines ran 80% as ramjets at high speeds (Mach 3.2). The SR-71 was dropped at the end of the Cold War, then brought back during the 1990s. They were used also in the Gulf War. The last SR-71 flight was in October 2001.

Scramjet aircraft

Scramjet aircraft are in the experimental stage. The Boeing X-43 is an experimental scramjet with a world speed record for a jet-powered aircraft - Mach 9.7, nearly 12,000 km/h (≈ 7,000 mph) at an altitude of about 36,000 meters (≈ 110,000 ft). The X-43A set the flight speed record on 16 November 2004.

History

Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.[5]

The dream of flight goes back to the days of pre-history. Many stories from antiquity involve flight, such as the Greek legend of Icarus and Daedalus, and the Vimana in ancient Indian epics. Around 400 BC, Archytas, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist, was reputed to have designed and built the first artificial, self-propelled flying device, a bird-shaped model propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have actually flown some 200 meters.[6][7] This machine, which its inventor called The Pigeon (Greek: Περιστέρα "Peristera"), may have been suspended on a wire or pivot for its flight.[8][9] Amongst the first recorded attempts at aviation were the attempts made by Yuan Huangtou in the 6th century and by Abbas Ibn Firnas in the 9th century. Leonardo da Vinci researched the wing design of birds and designed a man-powered aircraft in his Codex on the Flight of Birds (1502). In the 1630s, Lagari Hasan Çelebi flew in a rocket artificially powered by gunpowder. In the 18th century, Francois Pilatre de Rozier and Francois d'Arlandes flew in an aircraft lighter than air, a balloon. The biggest challenge became to create other craft, capable of controlled flight.

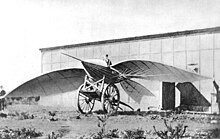

Sir George Cayley, the founder of the science of aerodynamics, was building and flying models of fixed-wing aircraft as early as 1803, and he built a successful passenger-carrying glider in 1853.[10] In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first powered flight, by having his glider "L'Albatros artificiel" pulled by a horse on a beach. On 28 August 1883, the American John J. Montgomery made a controlled flight in a glider. Other aviators who had made similar flights at that time were Otto Lilienthal, Percy Pilcher and Octave Chanute.

The first self-powered aircraft was created by an Englishman by the name of John Stringfellow of Chard in Somerset, who created a self-powered model aircraft that had its first successful flight in 1848.

Clément Ader constructed and designed a self-powered aircraft. On October 9, 1890, Ader attempted to fly the Éole, which succeeded in taking off and flying uncontrolled a distance of approximately 50 meters before witnesses.[citation needed] In August 1892 the Avion II flew for a distance of 200 meters, and on October 14, 1897, Avion III flew a distance of more than 300 meters.[citation needed]

The Wright Brothers made their first successful test flights on December 17, 1903. This flight is recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the standard setting and record-keeping body for aeronautics and astronautics, as "the first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight".[11] By 1905, the Wright Flyer III was capable of fully controllable, stable flight for substantial periods.

Alberto Santos-Dumont, a Brazilian living in France, built the first practical dirigible balloons at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1906, he flew the first fixed wing aircraft in Europe, 14-bis, which was of his and Gabriel Voisin's design. A later design of his, the Demoiselle, introduced ailerons and brought all around pilot control during a flight.[12]

World War I served as a testbed for the use of the aircraft as a weapon. Initially seen by the generals as a "toy", aircraft demonstrated their potential as mobile observation platforms, then proved themselves to be machines of war capable of causing casualties to the enemy. "Fighter aces" appeared, described as "knights of the air"; the greatest (by number of air victories) was the German Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. On the side of the allies, the ace with the highest number of downed aircraft was René Fonck, of France.

Following the war, aircraft technology continued to develop. Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic non-stop for the first time in 1919, a feat first performed solo by Charles Lindbergh in 1927. The first commercial flights took place between the United States and Canada in 1919. The turbine or the jet engine was in development in the 1930s; military jet aircraft began operating in the 1940s.

Aircraft played a primary role in the Second World War, having a presence in all the major battles of the war, Pearl Harbor, the battles of the Pacific, the Battle of Britain. They were an essential component of the military strategies of the period, such as the German Blitzkrieg or the American and Japanese aircraft carrier campaigns of the Pacific.

In October 1947, Chuck Yeager was the first person to exceed the speed of sound, flying the Bell X-1.

Aircraft in a civil military role continued to feed and supply Berlin in 1948, when access to railroads and roads to the city, completely surrounded by Eastern Germany, were blocked, by order of the Soviet Union.

The first commercial jet, the de Havilland Comet, was introduced in 1952. A few Boeing 707s, the first widely successful commercial jet, are still in service after nearly 50 years. The Boeing 727 was another widely used passenger aircraft, and the Boeing 747 was the world's biggest commercial aircraft between 1970 and 2005, when it was surpassed by the Airbus A380.

Designing and constructing an aircraft

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

Most aircraft are constructed by companies with the objective of producing them in quantity for customers. The design and planning process, including safety tests, can last up to four years for small turboprops, and up to 12 years for aircraft with the capacity of the A380.

During this process, the objectives and design specifications of the aircraft are established. First the construction company uses drawings and equations, simulations, wind tunnel tests and experience to predict the behavior of the aircraft. Computers are used by companies to draw, plan and do initial simulations of the aircraft. Small models and mockups of all or certain parts of the aircraft are then tested in wind tunnels to verify the aerodynamics of the aircraft.

When the design has passed through these processes, the company constructs a limited number of these aircraft for testing on the ground. Representatives from an aviation governing agency often make a first flight. The flight tests continue until the aircraft has fulfilled all the requirements. Then, the governing public agency of aviation of the country authorizes the company to begin production of the aircraft.

In the United States, this agency is the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and in the European Union, Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA). In Canada, the public agency in charge and authorizing the mass production of aircraft is Transport Canada.

In the case of the international sales of aircraft, a license from the public agency of aviation or transports of the country where the aircraft is also to be used is necessary. For example, aircraft from Airbus need to be certified by the FAA to be flown in the United States and vice versa, aircraft of Boeing need to be approved by the JAA to be flown in the European Union.

Quieter aircraft are becoming more and more needed due to the increase in air traffic, particularly over urban areas, as noise pollution is a major concern. MIT and Cambridge University have been designing delta-wing aircraft that are 25 times more silent (63 dB) than current craft and can be used for military and commercial purposes. The project is called the Silent Aircraft Initiative, but production models will not be available until around 2030. [3]

Small aircraft can be designed and constructed by amateurs as homebuilts. Other homebuilt aircraft can be assembled using pre-manufactured kits of parts which can be assembled into a basic aircraft and must then be completed by the builder.

Industrialized production

There are few companies that produce aircraft on a large scale. However, the production of an aircraft for one company is a process that actually involves dozens, or even hundreds, of other companies and plants, that produce the parts that go into the aircraft. For example, one company can be responsible for the production of the landing gear, while another one is responsible for the radar. The production of such parts is not limited to the same city or country; in the case of large aircraft manufacturing companies, such parts can come from all over the world.

The parts are sent to the main plant of the aircraft company, where the production line is located. In the case of large aircraft, production lines dedicated to the assembly of certain parts of the aircraft can exist, especially the wings and the fuselage.

When complete, an aircraft goes through a set of rigorous inspection, to search for imperfections and defects, and after being approved by the inspectors, the aircraft is tested by a pilot, in a flight test, in order to assure that the controls of the aircraft are working properly. With this final test, the aircraft is ready to receive the "final touchups" (internal configuration, painting, etc), and is then ready for the customer.

Safety

Comparisons

There are three main statistics which may be used to compare the safety of various forms of travel:[13]

| Deaths per billion journeys |

|---|

| Bus: 4.3 |

| Rail: 20 |

| Van: 20 |

| Car: 40 |

| Foot: 40 |

| Water: 90 |

| Air: 117 |

| Bicycle: 170 |

| Motorcycle: 1640 |

| Deaths per billion hours |

|---|

| Bus: 11.1 |

| Rail: 30 |

| Air: 30.8 |

| Water: 50 |

| Van: 60 |

| Car: 130 |

| Foot: 220 |

| Bicycle: 550 |

| Motorcycle: 4840 |

| Deaths per billion kilometres |

|---|

| Air: 0.05 |

| Bus: 0.4 |

| Rail: 0.6 |

| Van: 1.2 |

| Water: 2.6 |

| Car: 3.1 |

| Bicycle: 44.6 |

| Foot: 54.2 |

| Motorcycle: 108.9 |

It is worth noting that the air industry's insurers base their calculations on the "number of deaths per journey" statistic while the industry itself generally uses the "number of deaths per kilometre" statistic in press releases.[14]

Environmental impact

See also

- Aircraft

- Aircraft flight mechanics

- Aviation

- Aviation history

- List of altitude records reached by different aircraft types

- Rotorcraft

Notes

- ^ "Aeroplane", Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, 1989.

- ^ Lawrence Hargrave was one of the aviators to use the term "aeroplane" from an early date. "Is the air ship found?" New York Times, January 3, 1892.

- ^ Merriamirplane

- ^ 400 Hz Electrical Systems

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus. "Wikiquote Lord Kelvin", Letter to R. B. Hayward (1892), as quoted in Energy and Empire : A Biographical Study of Lord Kelvin (1989) by Crosbie Smith and M. Norton Wise

- ^ Aulus Gellius, "Attic Nights", Book X, 12.9 at LacusCurtius

- ^ ARCHYTAS OF TARENTUM, Technology Museum of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece

- ^ Modern rocketry [1]

- ^ Automata history [2]

- ^ "Cayley, Sir George." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 25 Aug. 2007 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9360092>.

- ^ FAI NEWS: 100 Years Ago, the Dream of Icarus Became Reality posted December 17, 2003, accessed January 5, 2007.

- ^ Alberto Santos-Dumont

- ^ The risks of travel

- ^ Flight into danger - 07 August 1999 - New Scientist Space

References

- In 1903 when the Wright brothers used the word "aeroplane" it meant wing, not the whole aircraft. See text of their patent. U.S. Patent 821,393 — Wright brothers' patent for "Flying Machine"

- Blatner, David. The Flying Book : Everything You've Ever Wondered About Flying On Airplanes. ISBN 0-8027-7691-4