Five Points, Manhattan

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

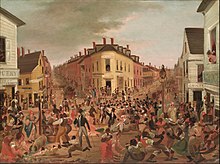

Five Points (or The Five Points) was a 19th-century neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. The neighborhood, partly built on low-lying land which had filled in the freshwater lake known as the Collect Pond, was generally defined as being bound by Centre Street to the west, the Bowery to the east, Canal Street to the north, and Park Row to the south. The Five Points gained international notoriety as a densely populated, disease-ridden, crime-infested slum which existed for over 70 years.[1]

Through the twentieth century, the former Five Points area was gradually redeveloped, with streets changed or closed. The area is now occupied by the Civic Center to the west and south, which includes major federal, state, and city facilities. To the east and north, the former Five Points neighborhood is now part of Manhattan's Chinatown.

Name

[edit]Two crossing streets and a third that ends at their intersection form five corners, or "points". About 1809, Anthony Street was extended east to the junction of Cross and Orange streets. As a result, the surrounding neighborhood came to be called Five Points.[2] In 1854, the three streets were renamed from Anthony Street to Worth Street, Orange Street to Baxter Street, and Cross Street to Park Street.[3] In 1868, Worth Street was again extended eastward, from the five-pointed intersection to Chatham Square, adding a sixth point.[4] Since then, Baxter (formerly Orange) has been eliminated south of the intersection and Park (formerly Cross) has been eliminated on both sides of it; thus, the junction of Baxter and Worth remaining today has only two corners.[5] Also, what remained of Park Street was renamed to Mosco Street in 1982.[6]

Collect Pond

[edit]

For the first two centuries of European settlement in Manhattan, the main source of drinking water for the growing city was Collect Pond, or Fresh Water Pond, which also supplied abundant fish.[8][9]

The pond occupied approximately 48 acres (190,000 m2) and was as deep as 60 feet (18 m).[8] Fed by an underground spring, it was located in a valley, with Bayard's Mount (at 110 feet or 34 metres, the tallest hill in lower Manhattan) to the northeast. A stream flowed north out of the pond and then west through a salt marsh (which, after being drained, became a meadow by the name of "Lispenard Meadows") to the Hudson River, while another stream issued from the southeastern part of the pond in an easterly direction to the East River. In the 18th century, the pond was used as a picnic area during summer and a skating rink during the winter.[10]

Beginning in the early 18th century, various commercial enterprises were built along the shores of the pond in order to use the water. These businesses included Coulthards Brewery, Nicholas Bayard's slaughterhouse on Mulberry Street (which was nicknamed "Slaughterhouse Street"),[11] numerous tanneries on the southeastern shore, and the pottery works of German immigrants Johan Willem Crolius and Johan Remmey on Pot Bakers Hill on the south-southwestern shore.[12] The contaminated wastewater of the businesses surrounding the pond flowed back into the pond, creating a severe pollution problem and environmental health hazard.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant proposed cleaning the pond and making it a centerpiece of a recreational park, around which the residential areas of the city could grow. His proposal was rejected, and it was decided to fill in the pond. The landfill was completed in 1811, and middle class homes were soon built on the reclaimed land.[13][8]

The landfill was poorly engineered. The buried vegetation began to release methane gas (a byproduct of decomposition) and the area, in a natural depression, lacked adequate storm sewers. As a result, the ground gradually subsided. Houses shifted on their foundations, the unpaved streets were often buried in a foot of mud mixed with human and animal excrement, and mosquitoes bred in the stagnant pools created by the poor drainage.

Most middle and upper class inhabitants fled the area, leaving the neighborhood open to poor immigrants who began arriving in the early 1820s. This influx reached a height in the 1840s, with large numbers of Irish Catholics fleeing the Great Famine.[14]

Slum

[edit]

At the height of Five Points' inhabitation, only parts of London's East End were equivalent in the western world for population density, child and infant mortality, disease, violent crime, unemployment, prostitution, and other classic problems of the urban destitute. It is sometimes considered the original American melting pot, at first consisting primarily of newly emancipated Black Americans (gradual emancipation led to the end of outright enslavement in New York on July 4, 1827) and ethnic Irish, who had a small minority presence in the area since the 1600s.[15] The local politics of "the Old Sixth ward" (The Points' primary municipal voting district), while not free of corruption, set important precedents for the election of Catholics to key political offices. Before that time, New York, and the United States at large, had been governed by the Anglo-Protestant founders. Although there were many tensions between Black Americans and the Irish, their cohabitation in Five Points was the first large-scale instance of voluntary racial integration in American history.[16] Gradually, this African-American community moved to Manhattan's West Side and to undeveloped lands on the north end of the island in the famous Harlem by the early 20th century and across the Harlem River into the South Bronx, as the city developed northward.[17]

Five Points is alleged to have had the highest murder rate of any slum at that time in the world. According to an old New York urban legend, the Old Brewery, formerly Coulthard's Brewery from the 1790s, then an overcrowded tenement on Cross Street housing 1,000 poor, is said to have had a murder a night for 15 years, until its demolition in 1852.[19][20]

Italians first settled in the Five Points in the 1850s. The parish of the Church of the Transfiguration at 25 Mott Street was largely Italian by the 1880s.[21] Mulberry Bend, named for the curve in Mulberry Street in the Chatham District, became the heart of Little Italy, which at its most populated was bordered on the south by Worth Street, on the east by the Bowery, and on the west by West Broadway.[22]

"Almack's" (also known as "Pete Williams's Place"), an African American-owned dance hall located at 67 Orange Street in Mulberry Bend (today Baxter Street), just south of its intersection with Bayard Street, was home to a fusion of Irish reels and jigs with the African shuffle.[23][24] Though different ethnic groups interacted in other parts of the United States as well, creating new dance and music forms, in New York this music and dance had spontaneously resulted on the street from competition between African-American and Irish musicians and dancers. It spilled into Almack's, where it gave rise in the short term to tap dance (see Master Juba) and in the long term to a music hall genre that was a major precursor to jazz and rock and roll. This ground is now Columbus Park.

Infectious diseases

[edit]Infectious diseases, such as cholera, tuberculosis, typhus, and malaria and yellow fever, had plagued New York City since the Dutch colonial era. The lack of scientific knowledge, sanitation systems, the numerous overcrowded dwellings, and absence of even rudimentary health care made impoverished areas such as Five Points ideal for the development and spread of these diseases. Several epidemics swept the City of New York in the 18th and 19th centuries, some of which originated in Five Points. Others were introduced by passengers disembarking from ships from overseas, including immigrants. In June 1832, an outbreak of cholera in Five Points spread rapidly throughout the crowded, unsanitary dwellings of the neighborhood before spreading to the rest of New York City.[25] With no understanding of disease vectors or transmission, some observers believed that these epidemics were due to the immorality of residents of the slum:

Every day's experience gives us assurance of the safety of the temperate and prudent, who are in circumstances of comfort …. The disease is now, more than before rioting in the haunts of infamy and pollution. A prostitute at 62 Mott Street, who was decking herself before the glass at 1 o'clock yesterday, was carried away in a hearse at half past three o'clock. The broken down constitutions of these miserable creatures, perish almost instantly on the attack …. But the business part of our population, in general, appear to be in perfect health and security. —New-York Mercury, July 18, 1832

Riots

[edit]The Anti-abolitionist riots of 1834, also known as the Farren Riots, occurred in New York City over a series of four nights, beginning July 7, 1834. Their deeper origins[26] lay in the combination of nativism and abolitionism among Protestants, who had controlled the city since the American Revolution, and the fear and resentment of Blacks among the growing numbers of Irish immigrants, who competed with them for jobs and housing.

In 1827, Great Britain repealed legislation controlling and restricting emigration from Ireland, and 20,000 Irish emigrated. By 1835, more than 30,000 Irish had arrived in New York annually. Among the casualties of the riots was St. Philip's Episcopal Church, the first black Episcopal church in the city, then located at 122 Centre Street. It was sacked and looted by the mostly ethnic Irish mob.[citation needed]

The media designated a branch of the "Roach Guards", a violent Irish gang, "Dead Rabbits". The Dead Rabbits Riot began when one faction destroyed the headquarters of the Bowery Boys at 26 Bowery, on July 4, 1857. The Bowery Boys retaliated, which led to a large-scale riot which raged back and forth on Bayard Street, between Bowery and Mulberry Street. Rioting resumed on July 5. The Bowery Boys and the Dead Rabbits fought again in front of 40 and 42 Bowery Street (original buildings still extant in May 2017), erecting barricades in the street. On July 6 the Bowery Boys fought the Kerryonians (Irishmen from County Kerry) at Anthony and Centre Street. Historian Tyler Anbinder says the "dead rabbits" name "so captured the imagination of New Yorkers that the press continued to use it despite the abundant evidence that no such club or gang existed". Anbinder notes that, "for more than a decade, 'Dead Rabbit' became the standard phrase by which city residents described any scandalously riotous individual or group."[27]

Brick-bats, stones and clubs were flying thickly around, and from the windows in all directions, and the men ran wildly about brandishing firearms. Wounded men lay on the sidewalks and were trampled upon. Now the Rabbits would make a combined rush and force their antagonists up Bayard street to the Bowery. Then the fugitives, being reinforced, would turn on their pursuers and compel a retreat to Mulberry, Elizabeth and Baxter streets.

As residents took advantage of the disorganized state of the city's police force, brought about by the conflict between the Municipal and Metropolitan police, gangsters and other criminals from all parts of the city began to engage in widespread looting and the destruction of property. The Daily National Intelligencer of July 8, 1857, estimated that between 800 and 1,000 gang members took part in the riots, along with several hundred others who used the disturbance to loot the Bowery area. It was the largest disturbance since the Astor Place Riot in 1849. Order was restored by the New York State Militia (under Major-General Charles W. Sandford), supported by detachments of city police. Eight people were reported killed, and more than 100 people received serious injuries.[28]

Social reform and renewal

[edit]

Various efforts by different charitable organizations and individuals, most of them Christian, attempted to alleviate the suffering of the poor in Five Points. Padre Felix Varela, a Cuban-born priest, established a Roman Catholic parish at the former Episcopalian Christ Church on Ann Street in 1827, to minister to the poor Irish Catholics. In 1836, Father Varela's parish was divided into two parishes, with one on James Street dedicated to St. James, and second one housed in a former Presbyterian church on Chambers Street, which was renamed the Church of the Transfiguration (Roman Catholic). In 1853, the parish relocated to the corner of Mott and Cross streets, when they purchased the building of the Zion Protestant Episcopal Church (c.1801) from its congregation, which moved uptown.

The first call for clearing the slums of Five Points through wholesale demolition came in 1829 from merchants who maintained businesses in close proximity to the neighborhood. Slum clearance efforts (promoted in particular by Jacob Riis, author of How the Other Half Lives, published 1890), succeeded in razing part of Mulberry Bend off Mulberry Street, one of the worst sections of the Five Points neighborhood. It was redeveloped as a park designed by noted landscape architect Calvert Vaux and named Mulberry Bend Park at its opening in 1897; it is now known as Columbus Park.[29]

That the place known as "Five points" has long been notorious... as being the nursery where every species of vice is conceived and matured; that it is infested by a class of the most abandoned and desperate character.... [They] are abridged from enjoying themselves in their sports, from the apprehension... that they may be enticed from the path of rectitude, by being familiarized with vice; and thus advancing step by step, be at last swallowed up in this sink of pollution, this vortex of irremediable infamy.... In conclusion your Committee remark, that this hot-bed of infamy, this modern Sodom, is situated in the very heart of your City, and near the centre of business and of respectable population.... Remove this nucleus—scatter its present population over a larger surface—throw open this part of your city to the enterprise of active and respectable men, and you will have effected much for which good men will be grateful.[note 1]

A major effort was made to clear the Old Brewery on Cross Street, described as "a vast dark cave, a black hole into which every urban nightmare and unspeakable fear could be projected."[30] The Old Brewery had formerly been Coulthard's Brewery, which was located on the outskirts of the town less than thirty years earlier in the 1790s. Later enveloped by the growing city, it was located on Cross Street just south of the Five Points intersection. The brewery became known as the "Old Brewery" after being converted to a tenement / boarding house in 1837. Its lower, high-ceilinged floor and the above two floors were converted into four floors of rundown apartments. The rent was cheap and attracted many low-income tenants, many of them immigrants. The only census record taken in 1850 reported 221 people living in 35 apartments, averaging 6.3 persons per apartment.[30] Accounts conflict as to the total number of people living in the Brewery flats, but all agreed that it was well over capacity.

The poverty seen throughout the Five Points was also displayed at the Old Brewery, and the women of the Home Mission took action. This Methodist charity group was determined to clean up Five Points. The Christian Advocate, also called The Christian Advocate and Journal, a weekly New York newspaper published by the Methodist Episcopal Church, reported on the ongoing project in October 1853:

In a meeting held in Metropolitan Hall, in December 1851, such convincing proof was given of the public interest in this project, that the resolution was passed by the Executive Committee to purchase the Old Brewery. Other appeals were made to the public, and nobly met. That celebrated haunt was purchased, in a few months utterly demolished, and already a noble missionary building occupies its site.[31]

The New Mission House replaced the Old Brewery, under the direction of the Five Points Mission. It provided housing, clothes, food, and education as part of the charitable endeavor. The new building had 58 rooms available for living space, twenty-three more than the Old Brewery.

The area today

[edit]The area formerly occupied by Five Points was gradually redeveloped through the twentieth century.[32] In the west and south, it is occupied by major federal, state, and city administration buildings and courthouses known collectively as Civic Center, Manhattan. In addition Columbus Park, Collect Pond Park, Foley Square, and various facilities of the New York City Department of Correction are clustered around lower Centre Street.[33] The Tombs jail/prison, in which many criminals from Five Points were incarcerated and quite a few executed, stood near the site of the City Prison Manhattan at 125 White Street;[34] the latter prison stood on the site until 2023.[35] The northeastern and eastern portion of Five Points is now within the sprawling Chinatown. Many tenement buildings dating from the late 19th century still line the streets in this area.

Since 2021, the intersection of Worth and Baxter streets has been co-named "Five Points", a reference to the former neighborhood.[32]

Notable people

[edit]- Paul Kelly, Italian American mobster and founder of the Five Points Gang, whose members included future crime bosses such as Johnny Torrio, Al Capone and Lucky Luciano

- John Morrissey, Irish American bare-knuckle boxer, Dead Rabbits gang criminal leader in New York City, Democratic Party New York State Senator, and Tammany Hall-backed U.S. Congressman from New York

- Mother Cabrini, an Italian nun, established her first orphanage to care for the orphans from five points in this neighborhood. Later her mission was expanded all over the world. She fought to give Italians dignity in an era when they were looked down upon by Americans.

In popular culture

[edit]Theatre

- Paradise Square (2018) is a musical play set in the Five Points that premiered at Berkeley Repertory Theatre December 27, 2018 – March 3, 2019.[36] The musical performed at Chicago's Nederlander Theatre from November 2 to December 5, 2021.[37] It started previews March 15, 2022, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway, where it ran from April 3[38] to July 17, 2022.[39]

Films

- Cabrini (2024), a biographical film about the Catholic saint Frances Xavier Cabrini (Mother Cabrini), features the support that Cabrini and her Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus provided to impoverished Italian immigrants in Five Points.

- Gangs of New York (2002) is a historical film set in the mid-19th century, in the Five Points district of New York City. The film, directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian, and Kenneth Lonergan, was inspired by Herbert Asbury's nonfiction book, The Gangs of New York (1928).

- The Sting (1973), a film about an elaborate scheme to 'con' a mob boss, Doyle Lonnegan, during the Depression to revenge a friend's murder in Illinois. Lonnegan grew up in Five Points, and one of the con men also claims his origin is Five Points.

Literature

- Hot Corn: Life Scenes in New York Illustrated (1854), by Solon Robinson, has stories about residents of Five Points.

- Edward Rutherfurd's historical novel New York is set, in part, in Five Points.

- May the Road Rise up to Meet You, by Peter Troy

- Winter's Tale, by Mark Helprin

- The Gods of Gotham, by Lyndsay Faye

- Lair of Dreams, young adult novel by Libba Bray

- Murder on Mulberry Bend, by Victoria Thompson (Gaslight Mystery series)

- Andersonville (1955), by MacKinlay Kantor, includes a description of the neighborhood in Chapter X.

- The Night Inspector (1999), by Frederick Busch, takes place in the neighborhood and describes parts of it in detail.

- City of Glory (2007), by Beverly Swerling, includes a description of the neighborhood’s development and some of its residents.

- Moon and the Mars (2021), young adult novel by Kia Corthron

Television

- Copper, BBC America's dramatic series, is set in the 1860s in the Five Points neighborhood.

- Hell on Wheels, season 3, episode 1, "Big Bad Wolf" (original air date August 10, 2013)

Music

- Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan's song "Never Let Go" contains the line: "down at the Five Points I stand", to suggest an ad extremum emotional and/or physical state.[40]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Board of Assistant Aldermen (October 24, 1831). "Petition to Have the Five Points Opened". Columbia University History Online. City of New York. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2020. "Merchants owning property along the periphery of Five Points petitioned the municipal government in 1829 to demolish the heart of the slum by widening and extending Anthony and Cross Streets."

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The First Slum in America". The New York Times. September 20, 2001. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Anbinder (2001), p. 444, note 13 to Chapter 1.

- ^ "Map of the Five Points Neighborhood, 1855-67", City University of New York American Social History Project. Accessed April 22, 2020.

- ^ Anbinder (2001), p. 345.

- ^ "Baxter and Worth Streets, looking south, July 2014" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ "Chinatown’s One-Block Mosco Street is the Last Remnant of Street in Five Points"

- ^ Pelletreau, William Smith (1900). Early New York Houses With Historical & Genealogical Notes. New York: Francis P. Harper. p. 214.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366., p. 250.

- ^ Solis, Julia. New York Underground: The Anatomy of a City. p. 76.

- ^ "The Hudson: A History" Tom Lewis (2007).

- ^ "Abattoirs.; History of New-York Slaughter-Houses-Interesting and Curious Data. (1866)". The New York Times.

- ^ "Craftsmen In Clay" @ www.corzilius.org

- ^ Kieran, John. A Natural History of New York. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8232-1086-2.

- ^ Delaney, Tim. American Street Gangs. pp. 39, 290.

- ^ Anbinder 2001.

- ^ "Gangs of New York". On Location Tours. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Timothy J. Gilfoyle (1992). City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790–1920. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-393-31108-2. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ "46 Mulberry Street, October 2019" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (August 26, 1990). "The City's Rough Past: Frighteningly Familiar [sic]". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ Walking Guide to New York.

- ^ "Little Italy" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ Aleandri, Emelise (2002). Little Italy. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. p. 10, caption. ISBN 0-7385-1062-9.

- ^ Asbury, Herbert. Gangs of New York Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark. The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. p. 157.

- ^ Peters, Stephanie True Peters. Cholera: Curse of the Nineteenth Century. p. 26.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G.; Wallace Mike (1999). "White, Green and Black", in Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. pp. 542–562.

- ^ Anbinder (2001), pp. 285–86.

- ^ "Rioting and Bloodshed; the Fight at Cow Bay. Metropolitans Driven from the 6th Ward". The New York Times. July 6, 1857. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "Columbus Park" Archived October 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

- ^ a b Anbinder (2001), pp. 67–70.

- ^ "The Five Points Mission". Christian Advocate and Journal (1833–1865). 28 (41): 162. October 13, 1853. ProQuest 126002159.

- ^ a b Gannon, Devin (October 14, 2021). "NYC's historic Five Points neighborhood is officially recognized with street co-naming". 6sqft. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Frishberg, Hannah (May 29, 2018). "New York's lost neighborhoods". Curbed NY. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Marcius, Chelsia Rose (October 17, 2020). "NYC's most notorious jail: a look back at The Tombs". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Chen, Stefanos; Chan, Mable (April 1, 2024). "Anger in New York Over Huge Chinatown Jail Project". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ Cristi, A.A. (January 31, 2019). "Berkeley Rep Extends PARADISE SQUARE Again!". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Meyer, Dan (May 18, 2021). "Broadway-Aimed Paradise Square Will Play Chicago". Playbill. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Brunner, Raven (March 15, 2022). "Paradise Square Begins Previews On Broadway March 15". Playbill. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Paulson, Michael (July 11, 2022). "'Paradise Square' Will Close on Broadway After Winning One Tony". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ "Tom Waits". tomwaits.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Anbinder, Tyler (April 2002). "From Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum". The American Historical Review. 107 (2). American Historical Association: 351–387. doi:10.1086/532290. PMID 12051257. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- Anbinder, Tyler (2001). Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World's Most Notorious Slum. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-85995-8.

External links

[edit]- McNamara, Robert J. (December 22, 2018). "The Five Points: New York's Most Notorious Neighborhood". ThoughtCo.com.

- Christiano, Gregory. "Where 'The Gangs' Lived—New York's Five Points". urbanography.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011.

- "Five Points". GSA.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2003. Retrieved November 28, 2003. Official site of the federal government's Five Points archaeological dig

- Article including contemporary news accounts of 1857 Police and Gang Riots

- "Frances Carle (Asbury)". Herbert Asbury. 2004. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- "Five Points". History of NY Chinatown. Includes a map of the area then, and now.