Amifampridine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Firdapse, Ruzurgi |

| Other names | pyridine-3,4-diamine, 3,4-diaminopyridine, 3,4-DAP |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 93–100%[5] |

| Metabolism | Acetylation to 3-N-acetylamifampridine |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5 hrs (amifampridine) 4 hrs (3-N-acetylamifampridine) |

| Excretion | Kidney (19% unmetabolized, 74–81% 3-N-acetylamifampridine) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL |

|

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.201 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

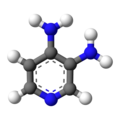

| Formula | C5H7N3 |

| Molar mass | 109.132 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 218 to 220 °C (424 to 428 °F) decomposes |

| Solubility in water | 24 |

| |

| |

| | |

Amifampridine is used as a drug, predominantly in the treatment of a number of rare muscle diseases. The free base form of the drug has been used to treat congenital myasthenic syndromes and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) through compassionate use programs since the 1990s and was recommended as a first line treatment for LEMS in 2006, using ad hoc forms of the drug, since there was no marketed form.

Around 2000 doctors at Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris created a phosphate salt form, which was developed through a series of companies ending with BioMarin Pharmaceutical which obtained European approval in 2009 under the brand name Firdapse, and which licensed the US rights to Catalyst Pharmaceuticals in 2012. As of January 2017, Catalyst and another US company, Jacobus Pharmaceutical, which had been manufacturing and giving it away for free since the 1990s, were both seeking FDA approval for their iterations and marketing rights.

Amifampridine phosphate has orphan drug status in the EU for Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome and Catalyst holds both an orphan designation and a breakthrough therapy designation in the US. In May 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved amifampridine tablets under the brand name Ruzurgi for the treatment of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) in people 6 to less than 17 years of age. This is the first FDA approval of a treatment specifically for pediatric patients with LEMS. The FDA granted the approval of Ruzurgi to Jacobus Pharmaceutical. The only other treatment approved for LEMS (Firdapse) is only approved for use in adults.[6]

Medical uses

[edit]Amifampridine is used to treat many of the congenital myasthenic syndromes, particularly those with defects in choline acetyltransferase, downstream kinase 7, and those where any kind of defect causes "fast channel" behaviour of the acetylcholine receptor.[7][8] It is also used to treat symptoms of Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome.[5][9]

Contraindications

[edit]Because it affects voltage-gated ion channels in the heart, it is contraindicated in people with long QT syndrome and in people taking a drug that might prolong QT time like sultopride, disopyramide, cisapride, domperidone, rifampicin or ketoconazol. It is also contraindicated in people with epilepsy or badly controlled asthma.[5]

Adverse effects

[edit]The dose-limiting side effects include tingling or numbness, difficulty sleeping, fatigue, and loss of muscle strength.[10]

Amifampridine can cause seizures, especially but not exclusively when given at high doses and/or in particularly vulnerable individuals who have a history of seizures.[5]

Interactions

[edit]The combination of amifampridine with pharmaceuticals that prolong QT time increases the risk of ventricular tachycardia, especially torsade de pointes; and combination with drugs that lower the seizure threshold increases the risk of seizures. Interactions via the liver's cytochrome P450 enzyme system are considered unlikely.[5]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]In Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome, acetylcholine release is inhibited as antibodies involved in the host response against certain cancers cross-react with Ca2+ channels on the prejunctional membrane. Amifampridine works by blocking potassium channel efflux in nerve terminals so that action potential duration is increased.[11] Ca2+ channels can then be open for a longer time and allow greater acetylcholine release to stimulate muscle at the end plate.[10]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Amifampridine is quickly and almost completely (93–100%) absorbed from the gut. In a study with 91 healthy subjects, maximum amifampridine concentrations in blood plasma were reached after 0.6 (±0.25) hours when taken without food, or after 1.3 (±0.9) hours after a fatty meal, meaning that the speed of absorption varies widely. Biological half-life (2.5±0.7 hrs) and the area under the curve (AUC = 117±77 ng∙h/ml) also vary widely between subjects, but are nearly independent of food intake.[5]

The substance is deactivated by acetylation via N-acetyltransferases to the single metabolite 3-N-acetylamifampridine. Activity of these enzymes (primarily N-acetyltransferase 2) in different individuals seems to be primarily responsible for the mentioned differences in half-life and AUC: the latter is increased up to 9-fold in slow metabolizers as compared to fast metabolizers.[5]

Amifampridine is eliminated via the kidneys and urine to 74–81% as N-acetylamifampridine and to 19% in unchanged form.[5]

Chemistry

[edit]3,4-Diaminopyridine is yellow solid, although commercial samples often appear brownish. It melts at about 218–220 °C (424–428 °F) with decomposition. Its density of 1.404 g/cm3.[12] It is readily soluble in alcohols and hot water, but only slightly in diethyl ether.[13][14] Solubility in water at 20 °C (68 °F) is 25 g/L.

The drug formulation amifampridine phosphate contains the phosphate salt, more specifically 4-aminopyridine-3-ylammonium dihydrogen phosphate.[14] This salt forms prismatic, monoclinic crystals (space group C2/c)[15] and is readily soluble in water.[16] The phosphate salt is stable, and does not require refrigeration.[17]

History

[edit]The development of amifampridine and its phosphate has brought attention to orphan drug policies that grant market exclusivity as an incentive for companies to develop therapies for conditions that affect small numbers of people.[18][19][20]

Amifampridine, also called 3,4-DAP, was discovered in Scotland in the 1970s, and doctors in Sweden first showed its use in LEMS in the 1980s.[21]

In the 1990s, doctors in the US, on behalf of Muscular Dystrophy Association, approached a small family-owned manufacturer of active pharmaceutical ingredients in New Jersey, Jacobus Pharmaceuticals, about manufacturing amifampridine so they could test it in clinical trials. Jacobus did so, and when the treatment turned out to be effective, Jacobus and the doctors were faced with a choice — invest in clinical trials to get FDA approval or give the drug away for free under a compassionate use program to about 200 patients out of the estimated 1500-3000 LEMS patients in the U.S.. Jacobus elected to give the drug away to this subset of LEMS patients, and did so for about twenty years.[22][23][24]

Doctors at the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris had created a phosphate salt of 3,4-DAP (3,4-DAPP), and obtained an orphan designation for it in Europe in 2002.[25] The hospital licensed the intellectual property on the phosphate form to the French biopharma company OPI, which was acquired by EUSA Pharma in 2007,[26] and the orphan application was transferred to EUSA in 2008.[25] In 2008 EUSA submitted an application for approval to market the phosphate form to the European Medicines Agency under the brand name Zenas.[27] EUSA, through a vehicle called Huxley Pharmaceuticals, sold the rights to 3,4-DAPP to BioMarin in 2009,[28] the same year that 3,4-DAPP was approved in Europe under the new name Firdapse.[25]

The licensing of Firdapse in 2010 in Europe led to a sharp increase in price for the drug. In some cases, this has led to hospitals using an unlicensed form rather than the licensed agent, as the price difference proved prohibitive. BioMarin has been criticized for licensing the drug on the basis of previously conducted research, and yet charging exorbitantly for it.[29] A group of UK neurologists and pediatricians petitioned to prime minister David Cameron in an open letter to review the situation.[30] The company responded that it submitted the licensing request at the suggestion of the French government, and points out that the increased cost of a licensed drug also means that it is monitored by regulatory authorities (e.g. for uncommon side effects), a process that was previously not present in Europe.[31] A 2011 Cochrane review compared the cost of the 3,4-DAP and 3,4-DAPP in the UK and found an average price for 3,4-DAP base of £1/tablet and an average price for 3,4-DAP phosphate of £20/tablet; and the authors estimated a yearly cost per person of £730 for the base versus £29,448 for the phosphate formulation.[9][17]

Meanwhile, in Europe, a task force of neurologists had recommended 3,4-DAP as the firstline treatment for LEMS symptoms in 2006, even though there was no approved form for marketing; it was being supplied ad hoc.[27]: 5 [32] In 2007 the drug's international nonproprietary name was published by the WHO.[33]

In the face of the seven-year exclusivity that an orphan approval would give to Biomarin, and of the increase in price that would accompany it, Jacobus began racing to conduct formal clinical trials in order to get approval for the free base form before BioMarin; its first Phase II trial was opened in January 2012.[34]

In October 2012, while BioMarin had a Phase III trial ongoing in the US, it licensed the US rights to 3,4-DAPP, including the orphan designation and the ongoing trial, to Catalyst Pharmaceuticals.[35] Catalyst anticipated that it could earn $300 to $900 million per year in sales at peak sales for treatment of people with LEMS and other indications, and analysts anticipated the drug would be priced at around. $100,000 in the US.[21] Catalyst went on to obtain a breakthrough therapy designation for 3,4-DAPP in LEMS in 2013,[36] an orphan designation for congenital myasthenic syndromes in 2015[37] and an orphan designation for myasthenia gravis in 2016.[38]

In August 2013, analysts anticipated that FDA approval would be granted to Catalyst in LEMS by 2015.[36]

In October 2014, Catalyst began making available under an expanded access program.[39]

In March 2015, Catalyst obtained an orphan designation for the use of 3,4-DAPP to treat of congenital myasthenic syndrome.[40] In April 2015, Jacobus presented clinical trial results with 3,4-DAP at a scientific meeting.[23]

In December 2015, a group of 106 neuromuscular doctors who had worked with both Jacobus and BioMarin/Catalyst published an editorial in the journal, Muscle & Nerve, expressing concern about the potential for the price of the drug to be dramatically increased should Catalyst obtain FDA approval, and stating that 3,4-DAPP represented no real innovation and didn't deserve exclusivity under the Orphan Drug Act, which was meant to spur innovation to meet unmet needs.[21][41] Catalyst responded to this editorial with a response in 2016 that explained that Catalyst was conducting a full range of clinical and non-clinical studies necessary to obtain approval in order to specifically address the unmet need among the estimated 1500-3000 LEMs patients since about 200 were receiving the product through compassionate use – and that this is exactly what the Orphan Drug Act was intended to do: deliver approved products to orphan drug populations so that all patients have full access.[42]

In December 2015, Catalyst submitted its new drug application to the FDA,[43] and in February 2016 the FDA refused to accept it, on the basis that it wasn't complete. In April 2016 the FDA told Catalyst it would have to gather further data.[44][18] Catalyst cut 30% of its workforce, mainly from the commercial team it was building to support an approved product, to save money to conduct the trials.[45] In March 2018 the company re-submitted its NDA.[46] The FDA approved amifampridine for the treatment of adults with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome on November 29, 2018.[47]

In February 2019, US Senator Bernie Sanders questioned the high price ($375,000) charged by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals for Firdapse.[48][49]

In May 2019, the privately held US company Jacobus Pharmaceutical, Princeton, New Jersey gained approval by the FDA for amifampridine tablets (Ruzurgi) for the treatment of LEMS in patients 6 to less than 17 years of age. This is the first FDA approval of a treatment specifically for pediatric patients with LEMS. Firdapse is only approved for use in adults.[6] Although Ruzurgi has been approved for pediatric patients, this approval makes it possible for adults with LEMS to get the drug off-label. Jacobus Pharmaceutical had been manufacturing and giving it away for free since the 1990s. The FDA decision dropped the stock of Catalyst Pharmaceuticals. The company's stock price has dropped about 50%.[50]

Research

[edit]Amifampridine has also been proposed for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS). A 2002 Cochrane systematic review found that there was no unbiased data to support its use for treating MS.[51] There was no change as of 2012.[52]

Isomazole is a drug that is made from an amifampridine precursor.[53][relevant?]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ruzurgi APMDS". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 24 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Updates to the Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy database". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 12 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Firdapse". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Ruzurgi". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Firdapse Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). EMA. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2015. See EMA Index page, product tab Archived 2018-09-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "FDA approves first treatment for children with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, a rare autoimmune disorder". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Argov Z (October 2009). "Management of myasthenic conditions: nonimmune issues". Current Opinion in Neurology. 22 (5): 493–497. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832f15fa. PMID 19593127. S2CID 10408557.

- ^ Abicht A, Müller J, Lochmüller H (14 July 2016). "Congenital Myasthenic Syndromes Overview". GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301347.

- ^ a b Keogh M, Sedehizadeh S, Maddison P (February 2011). "Treatment for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (2): CD003279. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003279.pub3. PMC 7003613. PMID 21328260.

- ^ a b Tarr TB, Wipf P, Meriney SD (August 2015). "Synaptic Pathophysiology and Treatment of Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome". Molecular Neurobiology. 52 (1): 456–463. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8887-2. PMC 4362862. PMID 25195700.

- ^ Kirsch GE, Narahashi T (June 1978). "3,4-diaminopyridine. A potent new potassium channel blocker". Biophysical Journal. 22 (3): 507–512. Bibcode:1978BpJ....22..507K. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(78)85503-9. PMC 1473482. PMID 667299.

- ^ Rubin-Preminger JM, Englert U (2007). "3,4-Diaminopyridine". Acta Crystallographica Section E. 63 (2): o757 – o758. Bibcode:2007AcCrE..63O.757R. doi:10.1107/S1600536807001444.

- ^ "Diaminopyridine (3,4-)" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 28 November 2015.. Index page: FDA Docket 98N-0812: Bulk Drug Substances to be Used in Pharmacy Compounding

- ^ a b Dinnendahl, V, Fricke, U, eds. (2015). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 1 (28th ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Mahé N, Nicolaï B, Allouchi H, Barrio M, Do B, Céolin R, et al. (2013). "Crystal Structure and Solid-State Properties of 3,4-Diaminopyridine Dihydrogen Phosphate and Their Comparison with Other Diaminopyridine Salts". Cryst Growth Des. 13 (2): 708–715. doi:10.1021/cg3014249.

- ^ Klement A (9 November 2015). "Firdapse". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (23/2015): 10f.

- ^ a b "Evidence Review: Amifampridine phosphate for the treatment of Lambert–Easton Myasthenic Syndrome" (PDF). NHS England. December 2015.

- ^ a b Tavernise S (17 February 2016). "F.D.A. Deals Setback to Catalyst in Race for Drug Approval". New York Times.

- ^ Drummond M, Towse A (May 2014). "Orphan drugs policies: a suitable case for treatment". The European Journal of Health Economics. 15 (4): 335–340. doi:10.1007/s10198-014-0560-1. PMID 24435513.

- ^ Lowe D (21 October 2013). "Catalyst Pharmaceuticals And Their Business Plan". In the Pipeline.

- ^ a b c Deak D (22 February 2016). "Jacobus and Catalyst Continue to Race for Approval of LEMS Drug". Bill of Health.

- ^ Silverman E (5 April 2016). "A family-run drug maker tries to stay afloat in the Shkreli era". STAT News.

- ^ a b "Jacobus Pharmaceuticals". Drug R&D Insight. 25 April 2015.

- ^ "BioMarin licenses North American rights to rare disease drug, invests $5M in Florida company". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "Public summary of opinion on orphan designation" (PDF). EMA. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Chapelle FX (4 November 2008). "OPi ou comment construire une biopharma en moins de dix ans - Private Equity Magazine". Private Equity Magazine (in French). Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Assessment report: Zenas" (PDF). EMA CHMP committee. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Huxley Acquisition Lands Biomarin New LEMS Treatment". Pharmaceutical Technology. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Goldberg A (21 November 2010). "Drug firms accused of exploiting loophole for profit". BBC News.

- ^ Nicholl DJ, Hilton-Jones D, Palace J, Richmond S, Finlayson S, Winer J, et al. (November 2010). "Open letter to prime minister David Cameron and health secretary Andrew Lansley". BMJ. 341: c6466. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6466. PMID 21081599. S2CID 24929143.

- ^ Hawkes N, Cohen D (November 2010). "What makes an orphan drug?". BMJ. 341: c6459. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6459. PMID 21081607. S2CID 2486975.

- ^ Vedeler CA, Antoine JC, Giometto B, Graus F, Grisold W, Hart IK, et al. (July 2006). "Management of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force". European Journal of Neurology. 13 (7): 682–690. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01266.x. PMID 16834698. S2CID 27161239.

- ^ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN) Recommended INN: List 58" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 21 (3). 2007.

- ^ Wahl M (25 January 2012). "Jacobus Begins Invitation-Only Trial of 3,4-DAP in LEMS". Muscular Dystrophy Association Quest Magazine Online.

- ^ Leuty R (31 October 2012). "BioMarin licenses North American rights to rare disease drug, invests $5M in Florida company". San Francisco Business Journal.

- ^ a b Baker DE (November 2013). "Breakthrough Drug Approval Process and Postmarketing ADR Reporting". Hospital Pharmacy. 48 (10): 796–798. doi:10.1310/hpj4810-796. PMC 3859287. PMID 24421428.

- ^ "Orphan Drug Designations: amifampridine phosphate for congenital myasthenic syndromes". FDA. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Orphan Drug Designations: amifampridine phosphate for myasthenia gravis". www.accessdata.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Radke J (29 October 2014). "Catalyst Using the Expanded Access Program to Conduct Phase IV Study with LEMS Patients". Rare Disease Report. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Orrphan designation congenital myasthenic syndromes". FDA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015.

- ^ Burns TM, Smith GA, Allen JA, Amato AA, Arnold WD, Barohn R, et al. (February 2016). "Editorial by concerned physicians: Unintended effect of the orphan drug act on the potential cost of 3,4-diaminopyridine". Muscle & Nerve. 53 (2): 165–168. doi:10.1002/mus.25009. PMID 26662952. S2CID 46855617.

- ^ McEnany PJ (January 2017). "A response to a recent editorial by concerned physicians on 3,4-diaminopyridine". Muscle & Nerve. 55 (1): 138. doi:10.1002/mus.25437. PMID 27756108.

- ^ Tavernise S (22 December 2015). "Patients Fear Spike in Price of Old Drugs". New York Times.

- ^ Adams B (26 April 2016). "Catalyst Pharmaceuticals hit by FDA extra studies request for Firdapse". FierceBiotech.

- ^ Adams B (17 May 2016). "Catalyst to ax 30% of workforce in wake of FDA trial demands". FierceBiotech.

- ^ Lima D (29 March 2018). "Catalyst Pharmaceuticals files new drug application with FDA". South Florida Business Journal.

- ^ "Firdapse (amifampridine phosphate) FDA Approval History". Drugs.com. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Bernie Sanders asks why drug, once free, now costs $375K". NBC News. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Family outraged over life-changing treatment going from free to $375,000 a year". NBC News. 8 February 2019.

- ^ Drash W (8 May 2019). "FDA undercuts $375,000 drug in surprise move". CNN Health. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Solari A, Uitdehaag B, Giuliani G, Pucci E, Taus C (2002). "Aminopyridines for symptomatic treatment in multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001330. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001330. PMC 7047571. PMID 12804404.

- ^ Sedehizadeh S, Keogh M, Maddison P (2012). "The use of aminopyridines in neurological disorders". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 35 (4): 191–200. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e31825a68c5. PMID 22805230. S2CID 41532252.

- ^ https://www.chemdrug.com/article/8/3284/16419479.html