Fionn mac Cumhaill

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

Fionn mac Cumhaill (/ˈfɪn məˈkuːl/ FIN mə-KOOL; Ulster Irish: [ˈfʲɪn̪ˠ mˠək ˈkuːl̠ʲ] Connacht Irish: [ˈfʲʊn̪ˠ-] Munster Irish: [ˈfʲuːn̪ˠ-]; Scottish Gaelic: [ˈfjũːn̪ˠ maxk ˈkʰũ.əʎ]; Old and Middle Irish: Find or Finn[1][2] mac Cumail or mac Umaill), often anglicized Finn McCool or MacCool, is a hero in Irish mythology, as well as in later Scottish and Manx folklore. He is the leader of the Fianna bands of young roving hunter-warriors, as well as being a seer and poet. He is said to have a magic thumb that bestows him with great wisdom. He is often depicted hunting with his hounds Bran and Sceólang, and fighting with his spear and sword. The tales of Fionn and his fiann form the Fianna Cycle or Fenian Cycle (an Fhiannaíocht), much of it narrated by Fionn's son, the poet Oisín.

Etymology

[edit]In Old Irish, finn/find means "white, bright, lustrous; fair, light-hued (of complexion, hair, etc.); fair, handsome, bright, blessed; in moral sense, fair, just, true".[3] It is cognate with Primitive Irish VENDO- (found in names from Ogam inscriptions), Welsh gwyn (cf. Gwyn ap Nudd),[4] Cornish gwen, Breton gwenn, Continental Celtic and Common Brittonic *uindo- (a common element in personal and place names), and comes from the Proto-Celtic adjective masculine singular *windos.[5][6][7]

Irish legend

[edit]Fionn's birth and early adventures are recounted in the narrative The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn and other sources. Fionn was the posthumous son of Cumhall, leader of the Fianna, by Muirne.[8]

Fionn and his father Cumhall mac Trénmhoir ("son of Trénmór") stem from Leinster, rooted in the tribe of Uí Thairsig ("the Descendants of Tairsiu")[9][10] There is mention of the Uí Thairsig in the Lebor Gabála Érenn as one of the three tribes descended from the Fir Bolg.[11]

His mother was called Muirne Muincháem "of the Fair Neck"[12] (or "of the Lovely Neck",[13] or "Muiren smooth-neck"[14]), the daughter of Tadg mac Nuadat (in Fotha Catha Chnucha) and granddaughter of Nuadat the druid serving Cathair Mór who was high-king at the time,[a][12] though she is described as granddaughter of Núadu of the Tuatha Dé Danann according to another source (Acallam na Senórach).[9] Cumhall served Conn Cétchathach "of the Hundred Battles" who was still a regional king at Cenandos (Kells, Co. Meath).[12][16]

Cumhall abducted Muirne after her father refused him her hand, so Tadg appealed to the high king Conn, who outlawed Cumhall. The Battle of Cnucha was fought between Conn and Cumhall, and Cumhall was killed by Goll mac Morna,[12] who took over leadership of the Fianna.

The feud

[edit]The Fianna were a band of warriors also known as a military order composed mainly of the members of two rival clans, "Clan Bascna" (to which Fionn and Cumall belonged) and "Clan Morna" (where Goll mac Morna belonged), the Fenians were supposed to be devoted to the service of the High King and to the repelling of foreign invaders.[17] After the fall of Cumall, Goll mac Morna replaced him as the leader of the Fianna,[18] holding the position for 10 years.[19]

Birth

[edit]Muirne was already pregnant; her father rejected her and ordered his people to burn her, but Conn would not allow it and put her under the protection of Fiacal mac Conchinn, whose wife, Bodhmall the druid, was Cumhall's sister. In Fiacal's house Muirne gave birth to a son, whom she called Deimne (/ˈdeɪni/ DAY-nee, Irish: [ˈdʲɪvʲ(ə)nʲə]),[b] literally "sureness" or "certainty", also a name that means a young male deer; several legends tell how he gained the name Fionn when his hair turned prematurely white.

Boyhood

[edit]Fionn and his brother Tulcha mac Cumhal were being hunted down by the Goll, the sons of Morna, and other men. Consequently, Finn was separated from his mother Muirne, and placed in the care of Bodhmall and the woman Liath Luachra ("Grey of Luachra"), and they brought him up in secret in the forest of Sliabh Bladma, teaching him the arts of war and hunting. After the age of six, Finn learned to hunt, but still had cause to flee from the sons of Morna.[20]

As he grew older he entered the service – incognito – of a number of local kings, but each one, when he recognised Fionn as Cumhal's son, told him to leave, fearing they would be unable to protect him from his enemies.

Thumb of Knowledge

[edit]Fionn was a keen hunter and often hunted with Na Fianna on the hill of Allen in County Kildare, it is believed by many in the area that Fionn originally caught the Salmon of Knowledge in the River Slate that flows through Ballyteague. The secret to his success thereafter when catching "fish of knowledge" was to always cast from the Ballyteague side of a river. He gained what commentators have called the "Thumb of Knowledge"[c] after eating a certain salmon, thought to be the Salmon of Wisdom.[22][23] The account of this is given in The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn.[24]

Young Fionn, still known by his boyhood name Demne, met the poet Finn Éces (Finnegas), near the river Boyne and studied under him. Finnegas had spent seven years trying to catch the salmon that lived in Fec's Pool (Old Irish: Linn Féic) of the Boyne, for it was prophesied the poet would eat this salmon, and "nothing would remain unknown to him".[24] Although this salmon is not specifically called the "Salmon of Knowledge", etc., in the text, it is presumed to be so, i.e., the salmon that fed on the nut[s] of knowledge at the well of Segais.[22] Eventually the poet caught it, and told the boy to cook it for him. While he was cooking it, Demne burned his thumb, and instinctively put his thumb in his mouth. This imbued him with the salmon's wisdom, and when Éces saw that he had gained wisdom, he gave the youngster the whole salmon to eat, and gave Demne the new name, Fionn.[24]

Thereafter, whenever he recited the teinm láida with his thumb in his mouth, the knowledge he wished to gain was revealed to him.[24][d]

In subsequent events in his life, Fionn was able to call on ability of the "Thumb of Knowledge", and Fionn then knew how to gain revenge against Goll.[citation needed] In the Acallam na Sénorach, the ability is referred to as "The Tooth of Wisdom" or "Tooth of Knowledge" (Old Irish: dét fis).[21]

Fionn's acquisition of the Thumb of Knowledge has been likened to the Welsh Gwion Bach tasting the Cauldron of Knowledge,[26] and Sigurðr Fáfnisbani tasting Fáfnir's heart.[27][28]

Fire-breather of the Tuatha de Danann

[edit]

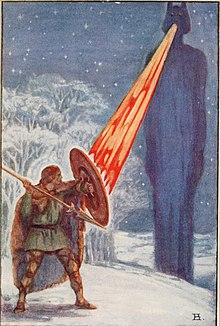

One feat of Fionn performed at 10 years of age according to the Acallam na Senórach was to slay Áillen (or [e]), the fire-breathing man of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who had come to wreak destruction on the Irish capital of Tara every year on the festival of Samhain for the past 23 years, lulling the city's men to sleep with his music then burning down the city and its treasures.[29]

When the King of Ireland asked what men would guard Tara against Áillen's invasion, Fionn volunteered.[f] Fionn obtained a special spear (the "Birga") from Fiacha mac Congha ("son of Conga"), which warded against the sleep-inducing music of Áillen's "dulcimer" (Old Irish: timpán)[g] when it was unsheathed and the bare steel blade was touched against the forehead or some other part of the body. This Fiacha used to be one of Cumall's men, but was now serving the high-king.[32]

After Fionn defeated Áillen and saved Tara, his heritage was recognised and he was given command of the Fianna: Goll stepped aside, and became a loyal follower of Fionn,[33][34] although a dispute later broke out between the clans over the pig of Slanga.[35]

Almu as eric

[edit]Before Fionn completed the feat of defeating the firebrand of the fairy mound and defending Tara, he is described as a ten-year-old "marauder and an outlaw".[36] It is also stated elsewhere that when Fionn grew up to become "capable of committing plunder on everyone who was an enemy", he went to his maternal grandfather Tadg to demand compensation (éric) for his father's death, on pain of single combat, and Tadg acceded by relinquishing the estate of Almu (the present-day Hill of Allen). Fionn was also paid éric by Goll mac Morna.[35][h]

Adulthood

[edit]Fionn's sword was called "Mac an Luinn".[38]

Love life

[edit]Fionn met his most famous wife, Sadhbh, when he was out hunting. She had been turned into a deer by a druid, Fear Doirich, whom she had refused to marry. Fionn's hounds, Bran and Sceólang, born of a human enchanted into the form of a hound, recognised her as human, and Fionn brought her home. She transformed back into a woman the moment she set foot on Fionn's land, as this was the one place she could regain her true form. She and Fionn married and she was soon pregnant. When Fionn was away defending his country, Fear Doirich (literally meaning Dark Man) returned and turned her back into a deer, whereupon she vanished. Fionn spent years searching for her, but to no avail. Bran and Sceólang, again hunting, found her son, Oisín, in the form of a fawn; he transformed into a child, and went on to be one of the greatest of the Fianna.

In The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne the High King Cormac mac Airt promises the aging Fionn his daughter Gráinne, but at the wedding feast Gráinne falls for one of the Fianna, Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, noted for his beauty. She forces him to run away with her and Fionn pursues them. The lovers are helped by the Fianna, and by Diarmuid's foster-father, the god Aengus. Eventually Fionn makes his peace with the couple. Years later, however, Fionn invites Diarmuid on a boar hunt, and Diarmuid is gored. Water drunk from Fionn's hands has the power of healing, but each time Fionn gathers water he lets it run through his fingers before he gets back to Diarmuid. His grandson Oscar shames Fionn, but when he finally returns with water it is too late; Diarmuid has died.

Death

[edit]According to the most popular account of Fionn's death, he is not dead at all, rather, he sleeps in a cave, surrounded by the Fianna. One day he will awake and defend Ireland in the hour of her greatest need. In one account, it is said that he will arise when the Dord Fiann, the hunting horn of the Fianna, is sounded three times, and he will be as strong and as well as he ever was.[39]

Popular folklore

[edit]Many geographical features in Ireland are attributed to Fionn. Legend has it he built the Giant's Causeway as stepping-stones to Scotland, so as not to get his feet wet; he also once scooped up part of Ireland to fling it at a rival, but it missed and landed in the Irish Sea – the clump became the Isle of Man, the pebble became Rockall, and the void became Lough Neagh. In Ayrshire, Scotland a common myth is that Ailsa Craig, a small islet just off coast of the said county, is another rock thrown at the fleeing Benandonner. The islet is sometimes referred to as "paddys' mile stone" in Ayrshire.[citation needed] Fingal's Cave in Scotland is also named after him, and shares the feature of hexagonal basalt columns with the nearby Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland.

In both Irish and Manx popular folklore,[40] Fionn mac Cumhail (known as "Finn McCool" or "Finn MacCooill" respectively) is portrayed as a magical, benevolent giant. The most famous story attached to this version of Fionn tells of how one day, while making a pathway in the sea towards Scotland – The Giant's Causeway – Fionn is told that the giant Benandonner (or, in the Manx version, a buggane) is coming to fight him. Knowing he cannot withstand the colossal Benandonner, Fionn asks his wife Oona to help him. She dresses her husband as a baby, and he hides in a cradle; then she makes a batch of griddle-cakes, hiding griddle-irons in some. When Benandonner arrives, Oona tells him Fionn is out but will be back shortly. As Benandonner waits, he tries to intimidate Oona with his immense power, breaking rocks with his little finger. Oona then offers Benandonner a griddle-cake, but when he bites into the iron he chips his teeth. Oona scolds him for being weak (saying her husband eats such cakes easily), and feeds one without an iron to the 'baby', who eats it without trouble.

In the Irish version, Benandonner is so awed by the power of the baby's teeth and the size of the baby that, at Oona's prompting, he puts his fingers in Fionn's mouth to feel how sharp his teeth are. Fionn bites Benandonner's little finger, and scared of the prospect of meeting his father considering the baby's size, Benandonner runs back towards Scotland across the Causeway smashing the causeway so Fionn can't follow him.

The Manx Gaelic version contains a further tale of how Fionn and the buggane fought at Kirk Christ Rushen. One of Fionn's feet carved out the channel between the Calf of Man and Kitterland, the other carved out the channel between Kitterland and the Isle of Man, and the buggane's feet opened up Port Erin. The buggane injured Fionn, who fled over the sea (where the buggane could not follow), however, the buggane tore out one of his own teeth and struck Fionn as he ran away. The tooth fell into the sea, becoming the Chicken Rock, and Fionn cursed the tooth, explaining why it is a hazard to sailors.

In Newfoundland, and some parts of Nova Scotia, "Fingal's Rising" is spoken of in a distinct nationalistic sense. Made popular in songs and bars alike, to speak of "Fingle," as his name is pronounced in English versus "Fion MaCool" in Newfoundland Irish, is sometimes used as a stand-in for Newfoundland or its culture.

Folktales involving hero Fin MacCool are considered to be classified in Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 369, "The Youth on a Quest for his lost Father",[41] a tale type that, however, some see as exclusive to South Asian tradition, namely India.[42][43][44]

Historical hypothesis

[edit]The 17th-century historian Geoffrey Keating, and some Irish scholars of the 19th century,[i] believed that Fionn was based on a historical figure.[45]

The 19th century scholar Heinrich Zimmer suggested that Fionn and the Fenian Cycle came from the heritage of the Norse-Gaels.[46] He suggested the name Fianna was an Irish rendering of Old Norse fiandr "enemies" > "brave enemies" > "brave warriors".[46] He also noted the tale of Fionn's Thumb of Knowledge is similar to the Norse tale of Sigurðr and Fáfnir,[27][47] although similar tales are found in other cultures. Zimmer proposed that Fionn might be based on Caittil Find (d. 856) a Norseman based in Munster, who had a Norse forename (Ketill) and an Irish nickname (Find, "the Fair" or "the White"). But Ketill's father must have had some Norse name also, certainly not Cumall, and the proposal was thus rejected by George Henderson.[48][45]

Toponymy

[edit]Fionn Mac Cumhaill was said to be originally from Ballyfin, in Laois.[49] The direct translation of Ballyfin from Irish to English is "town of Fionn".

Retellings

[edit]T. W. Rolleston compiled both Fenian and Ultonian cycle literature in his retelling, The High Deeds of Finn and other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland (1910).[50]

James Stephens published Irish Fairy Tales (1920), which is a retelling of a few of the Fiannaíocht.[51]

Modern literature

[edit]

Macpherson's Ossian

[edit]Fionn MacCumhail was transformed into the character "Fingal" in James Macpherson's poem cycle Ossian (1760), which Macpherson claimed was translated out of discovered Ossianic poetry written in the Scottish Gaelic language.[52] "Fingal", derived from the Gaelic Fionnghall, was possibly Macpherson's rendering Fionn's name as Fingal based on a misapprehension of the various forms of Fionn.[53] His poems had widespread influence on writers, from the young Walter Scott to Goethe, but there was controversy from the outset about Macpherson's claims to have translated the works from ancient sources. The authenticity of the poems is now generally doubted, though they may have been based on fragments of Gaelic legend, and to some extent the controversy has overshadowed their considerable literary merit and influence on Romanticism.[citation needed]

Twentieth century literature

[edit]Fionn mac Cumhaill features heavily in modern Irish literature. Most notably he makes several appearances in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake (1939) and some have posited that the title, taken from the street ballad "Finnegan's Wake", may also be a blend of "Finn again is awake", referring to his eventual awakening to defend Ireland.

Fionn also appears as a character in Flann O'Brien's comic novel, At Swim-Two-Birds (1939), in passages that parody the style of Irish myths. Morgan Llywelyn's book Finn Mac Cool (1994) tells of Fionn's rise to leader of the Fianna and the love stories that ensue in his life. That character is celebrated in "The Legend of Finn MacCumhail", a song by the Boston-based band Dropkick Murphys featured on their album Sing Loud Sing Proud!.

Glencoe: The Story of the Massacre by John Prebble (Secker & Warburg, 1966), has an account of a legendary battle between Fionn mac Cumhaill, who supposedly lived for a time in Glencoe (in Scotland), and a Viking host in forty longships which sailed up the narrows by Ballachulish into Loch Leven. The Norsemen were defeated by the Feinn of the valley of Glencoe, and their chief Earragan was slain by Goll MacMorna.

The High Deeds of Finn MacCool, an evocative children's novel by Rosemary Sutcliffe, was published in 1969.

"Finn Mac Cool" written by American author, Morgan Llywelyn, was released in 1994. The fictional novel vividly recounts Finn's historical adventures saturated with myth and magic. A childhood spent in exile, the love and loss of his beloved wife and child, and his legendary rise from a low class slave to leader of the invincible Fianna.

Finn McCool is a character in Terry Pratchett's and Steve Baxter's The Long War.

The adventures of Fion Mac Cumhail after death is explored by the novella "The Final Fighting of Fion Mac Cumhail" by Randall Garrett (Fantasy and Science Fiction – September 1975).

Finn's early childhood and education is explored in 'Tis Himself: The Tale of Finn MacCool by Maggie Brace.

Other stories featuring Fionn Mac Cumhail are two of three of the stories in The Corliss Chronicles the story of Prudence Corliss. In the stories, he is featured in The Wraith of Bedlam and The Silver Wheel. He is a close confidant to Prudence and allies himself with her to defeat the evil fictional king Tarcarrius.

Plays and shows

[edit]In 1987 Harvey Holton (1949–2010) published Finn with the Three Tygers Press, Cambridge. This was a dramatic cycle of poems in Scots for the stage and with music by Hamish Moore, based on the legends of Finn McCool and first performed at The Edinburgh Festival in 1986 before going on tour around Scotland.

In the 1999 Irish dance show Dancing on Dangerous Ground, conceived and choreographed by former Riverdance leads, Jean Butler and Colin Dunne, Tony Kemp portrayed Fionn in a modernised version of The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne. In this, Diarmuid, played by Colin Dunne, dies at the hands of the Fianna after he and Gráinne, played by Jean Butler, run away together into the forests of Ireland, immediately after Fionn and Gráinne's wedding. When she sees Diarmuid's body, Gráinne dies of a broken heart.

In 2010, Washington DC's Dizzie Miss Lizzie's Roadside Revue debuted their rock musical Finn McCool at the Capitol Fringe Festival. The show retells the legend of Fionn mac Cumhaill through punk-inspired rock and was performed at the Woolly Mammoth Theater in March 2011.[54]

See also

[edit]- Irish mythology in popular culture: Fionn mac Cumhaill

- Fenian Brotherhood – a 19th-century Irish revolutionary organisation taking its name from these Fionn legends.

- Daolghas

- Belfast Giants – ice hockey club based in Belfast whose mascot is derived from Fionn

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tadg mac Nuadat was also a druid, and the clan lived on the hill of Almu, now in County Kildare.[15]

- ^ Southern Irish: [ˈdʲəinʲə].

- ^ "Tooth of Knowledge/Wisdom" in the Acallam na Sénorach[21]

- ^ The teinm láida, glossed as "illumination (?) of song" by Meyer, is described as "one of the three things that constitute a poet" in this text,[24] but glossed by the 12th century Sanas Chormaic as one of the three methods of acquiring prophetic knowledge.[25]

- ^ The episode is also briefly told in Macgnímartha Finn, but there the name of the TDD villain is Aed .

- ^ The Fenians were supposed to be devoted to the service of the High King and to the repelling of foreign invaders.[17]

- ^ It is not clear what sort of stringed instrument.[30] O'Grady's translation leaves the word in the original Irish, and O'Dooley and Roe as "dulcimer". T. W. Rolleston rendered it as a "magic harp",[31] though he uses the term "tympan" elsewhere.

- ^ In the Acallamh na Sénorach, the recollection of the Birga event is preceded by an explanation of Almu, which says Cumhall fathered a son by Alma daughter of Bracan, who died of childbirth. Fionn is not specifically mentioned until Caílte follows up with a story involving Almu that took place in the time of Conn's grandson Cormac.[37]

- ^ John O'Donovan and Eugene O'Curry. Also W. M. Hennessy before having a change of heart.

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Meyer, Kuno, ed. (1897), "The Death of Finn Mac Cumaill", Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, 1: 462–465, doi:10.1515/zcph.1897.1.1.462, S2CID 202553713text via CELT Corpus.

- ^ Stokes (1900), pp. xiv+1–438.

- ^ Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, finn-1; dil.ie/22134

- ^ Williams, Mark (2017). Ireland's Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 194-247 [198]. doi:10.1515/9781400883325-009.

Linguistically cognate with Irish Finn is Welsh Gwynn, a figure who appears in Welsh tradition as a supernatural hunter ...

- ^ Sims-Williams, Patrick (1990). "Some Celtic Otherworld Terms". Celtic Language, Celtic Culture: a Festschrift for Eric P. Hamp. Ford & Bailie Publishers. p. 58.

- ^ Matasovic, Ranko, Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill, 2009. p. 423.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Editions Errance, 2003 (2nd ed.). p. 321.

- ^ Meyer (1904) tr. The Boyish Exploits of Finn, pp. 180–181

- ^ a b Stokes (1900) ed. Acallm. 6645–6564 Cumhall mac Treduirn meic Trénmhoir; O'Grady (1892a) ed., p. 216 Cumhall mac Thréduirn mheic Chairbre ; O'Grady (1892b) tr. p. 245 Cumall son of Tredhorn son of Cairbre; Dooley & Roe (1999), pp. 183–184: "Cumall, son of Tredhorn, son of Trénmór

- ^ Meyer (1904) tr. The Boyish Exploits of Finn, p. 180

- ^ Macalister, R. A. S. (1941) ed. tr. LGE ¶282 pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c d Hennessy, William Maunsell, ed. (1875), "Battle of Cnucha", Revue Celtique, 2: 86–93 (ed. "Fotha Catha Cnucha inso" , tr. "The Cause of the Battle of Cnucha here"). archived via Internet Archive.

- ^ Dooley & Roe (1999), pp. 183–184.

- ^ O'Grady (1892b), p. 245.

- ^ Fotha Catha Cnucha, Hennessy (1875), p. 92, note 7: "Almu. hill of Allen, near Newbridge in the country of Kildare".

- ^ Windisch, Ernst, ed. (1875), Fotha Catha Cnucha in so, 2, pp. 86–93, Wórterbuch, p. 127: "Cenandos", now Kells.

- ^ a b Rolleston, T. W. (1911). "Chapter VI: Tales of the Ossianic Cycle". Hero-tales of Ireland. Constable. p. 252. ISBN 9780094677203.

- ^ Macgnímartha Find, Meyer (1904), pp. 180–181 and verse.

- ^ Acallam na Senórach, O'Grady (1892b), p. 142. That is, until Finn at age ten saved Tara from Aillen of the Tuatha Dé Danann, cf. infra.

- ^ cf. Macgnímartha Find, Meyer (1904), pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b Acallam na Senórach 203, Stokes (1900) ed., p. 7 and note to line 203, p. 273; Dooley & Roe (1999), p. 9 and note on p. 227.

- ^ a b Scowcroft (1995), p. 152.

- ^ "knowledge", Mackillop (1998) ed., Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, p. 287

- ^ a b c d e Meyer (1904) tr. The Boyish Exploits of Finn, pp. 185–186; Meyer (1881) ed., p. 201

- ^ "teinm laída", Mackillop (1998) ed., Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology

- ^ Scowcroft (1995), pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Scowcroft (1995), p. 154

- ^ Scott, Robert D. (1930), The thumb of knowledge in legends of Finn, Sigurd, and Taliesin, New York: Institute of French Studies

- ^ Stokes (1900) ed. Acallm. 1654–1741; O'Grady (1892a) ed., pp. 130–132 O'Grady (1892b) tr. pp. 142–145; Dooley & Roe (1999), pp. 51–54

- ^ eDIL s.v. "timpán", 'some kind of stringed instrument ; a psaltery (?) '.

- ^ Rolleston (1926), p. 117.

- ^ Acallam na Senórach, O'Grady (1892b) tr. pp. 142–144; Dooley & Roe (1999), pp. 51–53

- ^ Acallamh na Sénorach, O'Grady (1892b) tr. pp. 144–145; Dooley & Roe (1999), p. 53–54

- ^ cf. Macgnímartha Find, Meyer (1904), p. 188 and verse.

- ^ a b Fotha Catha Cnucha, Hennessy (1875), pp. 91–92 and verse.

- ^ Acallamh na Sénorach, O'Grady (1892b) tr. p. 142; Dooley & Roe (1999), p. 52: "an outcast engaged in scavenging".

- ^ Acallamh na Sénorach, O'Grady (1892b) tr. pp. 131–132; Dooley & Roe (1999), pp. 39–40

- ^ "BBC Radio nan Gàidheal – Litir do Luchd-ionnsachaidh, Litir do Luchd-ionnsachaidh". BBC. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Lynch, J.F. (1896). "The Legend of Birdhill". Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. 2. II. Cork Historical and Archaeological Society: 188.

- ^ Manx Fairy Tales, Peel, L. Morrison, 1929

- ^ Harvey, Clodagh Brennan. Contemporary Irish Traditional Narrative: The English Language Tradition. Berkeley; Los Angeles; Oxford: University of California Press. 1992. pp. 80-81 (footnote nr. 26). ISBN 0-520-09758-0

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. p. 128.

- ^ Beck, B. E. F. "Frames, Tale Types and Motifs: The Discovery of Indian Oicotypes". In: Indian Folklore Volume II. eds. P. J. Claus et al. Mysore: 1987. pp. 1–51.

- ^ Islam, Mazharul. Folklore, the Pulse of the People: In the Context of Indic Folklore. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. 1985. pp. 100 and 166.

- ^ a b Mackillop (1985), pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Heinrich (1891). Keltische Beiträge III, in: Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum und deutsche Litteratur (in German). Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. pp. 1–171.

- ^ Scott, Robert D. (1930), The thumb of knowledge in legends of Finn, Sigurd, and Taliesin, New York: Institute of French Studies

- ^ Henderson (1905), pp. 193–195.

- ^ "Birthplace of Fionn Mac Cumhaill- Ballyfin, Co. Laois". 4 June 2020.

- ^ Rolleston, T. W. (1926) [1910]. "The Coming of Lugh". The High Deeds of Finn and other Bardic Romances of Ancient Ireland. George G. Harrap. pp. 105ff.

- ^ Irish Fairy Tales (Wikisource).

- ^ Hanks, P; Hardcastle, K; Hodges, F (2006) [1990]. A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford Paperback Reference (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 402, 403. ISBN 978-0-19-861060-1.

- ^ "Notes to the first edition". Sundown.pair.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Judkis, Maura. "TBD Theater: Finn McCool". TBD. TBD.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- Bibliography

- Tales of the Elders of Ireland. Translated by Dooley, Ann; Roe, Harry. Oxford University Press. 1999. pp. 152–154, 155–158, 174–176 (and endnote) p. 171ff. ISBN 978-0-192-83918-3.

- O'Grady, Standish H., ed. (1892a), "Agallamh na Senórach", Silva Gadelica, Williams and Norgate, pp. 94–232

- O'Grady, Standish H., ed. (1892b), "The Colloquy with the Ancients", Silva Gadelica, translation and notes, Williams and Norgate, pp. 101–265

- Stokes, Whitley, ed. (1900), Acallamh na Seanórach; Tales of the Elders, Irische Texte IV. e-text via CELT corpus.

- (other)

- Henderson, George (16 January 1905), "The Fionn Saga", Folk-lore, 28, London: 193–207, 353–366

- Meyer, Kuno (1881), "Macgnimartha Find", Revue Celtique, 5: 195–204, 508

- Meyer, Kuno (1904), "The Boyish Exploits of Finn" [tr. of Macgnimartha Find], Ériu, 1: 180–190

- Mackillop, James (1985), Fionn mac Cumhail: Celtic Myth in English Literature, London: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 9780815623533

- Scowcroft, Richard Mark (1995), "Abstract Narrative in Ireland", Ériu, 46: 121–158, JSTOR 30007878

External links

[edit]- "The Connection Between Fenian Lays, Liturgical Chant, Recitative, and Dán Díreach: a Pre-Medieval Narrative Song Tradition." An analysis of how the songs (lays) of Fionn Mac Cumhaill may have been sung.

- Fionn MacCool and the Old Man." Montreal storyteller JD Hickey tells a classic Fionn MacCool story.

- The Wisdom of the Outlaw: The Boyhood Deeds of Finn in Gaelic Narrative Tradition, Joseph Falaky Nagy. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985. ix + 338 pp. Bibliography; Index.

- Quiggin, Edmund Crosby (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).