Fingal mac Gofraid

Fingal mac Gofraid, and his father, Gofraid mac Sitriuc, were late eleventh-century rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles.[note 1] Although one source states that Gofraid mac Sitriuc's father was named Sitriuc, there is reason to suspect that this could be an error of some sort. There is also uncertainty as to which family Gofraid mac Sitriuc belonged to. One such family, descended from Amlaíb Cúarán, King of Northumbria and Dublin, appears to have cooperated with Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó, King of Leinster. Another family, that of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles, opposed Amlaíb Cúarán's apparent descendants, and was closely connected with Diarmait's adversaries, the Uí Briain kindred.

If Gofraid mac Sitriuc was a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán, it could mean that he was installed in the Isles by Diarmait after the latter oversaw the apparent expulsion of Echmarcach in the 1060s. Membership of this family may also explain apparent amiable relationship that Gofraid mac Sitriuc and Fingal appear to have enjoyed with Gofraid Crobán, their immediate successor in the Isles. It could also explain an attack on Mann in 1073, conducted by a possible the Uí Briain and a possible kinsman of Echmarcach. On the other hand, if Gofraid mac Sitriuc was a close kinsman of Echmarcach, it is possible that he is identical to Gofraid ua Ragnaill, King of Dublin, a contemporary ruler who is known to have reigned in Dublin during a period of Uí Briain overlordship after Diarmait's death. This identification could mean that Gofraid ua Ragnaill immediately succeeded Echmarcach in both Dublin and the Isles.

Gofraid mac Sitriuc is stated in one source to have died in about 1070, after which Fingal succeeded him. Fingal later appears to have fended off an attack upon Mann by men with Irish connections. At some point in the 1070s the kingdom was conquered by Gofraid Crobán, although the circumstances of this event are uncertain. Whilst it is possible that the latter overthrew Fingal, this is by no means certain. In fact, the throne may well have been vacant when Gofraid Crobán conducted his campaigns to gain the kingship. Whatever the case, there is reason to suspect that descendants of Fingal ruled the Kingdom of the Rhinns following his demise.

Uncertain parentage and identity

[edit]

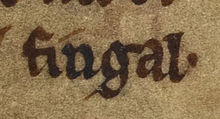

Gofraid mac Sitriuc is specifically mentioned twice by the Chronicle of Mann: once as "Godredum filium Sytric", and once as "Godredus filius Sytric".[12] Although these passages seem to show that his father's name was Sitriuc, the first instance of "Sytric" is crossed out, and the corresponding marginal notes beside both passages read "Fingal".[11] These passages, therefore, may be evidence that Gofraid mac Sitriuc was either the son of a man named Sitriuc, or else the son of a man named Fingal.[13] It is also possible that the marginal note refers to a place name rather than a personal name. For example, the notes could refer to Fine Gall,[14] Dublin's agriculturally rich northern hinterland.[15] The notes, therefore, could be evidence that Gofraid mac Sitriuc was a native Dubliner rather than a Manxman.[14][note 2] If Gofraid mac Sitriuc's father was indeed named Sitriuc, there are several contemporaneous candidates.[19]

One particular candidate is Sitriuc mac Ímair, King of Waterford, however there is no evidence that this man had a son named Gofraid.[13] Another candidate is Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, King of Dublin.[20] Although this man is known to have had a son named Gofraid, the latter is recorded to have been killed in 1036. This Sitriuc, however, is known to have had two sons named Amlaíb, one who died in 1013, and the other who died in 1036.[21] In fact, it was not uncommon for parents to have several children with the same name,[14] and it is possible that Sitriuc mac Amlaíb was the father of not only two Amlaíbs but two Gofraids as well.[19] Another candidate is an alleged descendant of Sitriuc mac Amlaíb's brother, Glún Iairn mac Amlaíb, King of Dublin. Specifically, according to a genealogical tract preserved by the seventeenth-century scribe Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh, Glún Iairn had an otherwise unknown son named Sitriuc, a man who conceivably could have been Gofraid mac Sitriuc's father.[22][note 3]

Another possibility is that Gofraid mac Sitriuc is identical to the contemporaneous like-named King of Dublin, Gofraid ua Ragnaill.[25] The latter's name is recorded variously in the Irish annals: the Annals of Inisfallen calls him "Goffraid mc. meicc Ragnaill",[26] and "Goffraid h-ua Regnaill",[27] whilst the Annals of Ulster calls him "Gofraigh mc. Amhlaim uel mc Raghnaill".[28] Although the evidence regarding Gofraid ua Ragnaill could indicate that his father was named Amlaíb, who was in turn the son of a man named Ragnall,[29] the latter annal-entry literally states that he was the "son of Amlaíb or son of Ragnall", potentially indicating confusion in regard to his parentage.[30] In any event, the annal-entries suggest that Gofraid ua Ragnaill was closely related to Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles.[30] Gofraid ua Ragnaill, therefore, could have been the son of a brother of Echmarcach named either Amlaíb or Sitriuc,[31] or else perhaps even a son of Echmarcach himself.[30]

Background

[edit]

In the mid eleventh century, Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó, King of Leinster extended his authority into Dublin and the Isles at Echmarcach's expense. Specifically, Diarmait conquered Dublin in 1152, assumed the kingship, and thereby forced Echmarcach to flee "over the sea".[32] About ten years later, Echmarcach appears to have been driven from Mann altogether, as the island was raided by Diarmait's son, Murchad, who received tribute and defeated a certain "mac Ragnaill", who may well have been Echmarcach himself.[33] Echmarcach eventually died in Rome, in 1064[34] or 1065.[35] On his death, the contemporary eleventh-century chronicler Marianus Scotus described him in Latin as "rex Innarenn",[36] a title that could either mean "King of the Isles",[37] or "King of the Rhinns".[38] If it represents the latter, it could be evidence that Echmarcach's once expansive sea-kingdom had gradually eroded to territory in Galloway only.[39][note 4]

For twenty years after Echmarcach's expulsion from Dublin, Diarmait enjoyed the overlordship of the coastal kingdom, and the control of its highly rated army and prized fleet of warships.[41] On his unexpected death in 1072, however, Toirdelbach Ua Briain, King of Munster invaded Leinster, and followed up on this military success with the acquisition of Dublin itself.[42] There is uncertainty as to when Gofraid ua Ragnaill assumed the kingship of Dublin. On one hand, he could have succeeded Echmarcach before Diarmait's fall.[30] On the other hand, Toirdelbach may have handed the region over to him following the Uí Briain takeover,[43] or at least consented to Gofraid ua Ragnaill's establishment under his own overlordship.[44]

Implications of familial uncertainty

[edit]The uncertainty surrounding Gofraid mac Sitriuc's parentage means that he could have been a member of any of several families. One such family—that of the kings Sitriuc mac Amlaíb and Glún Iairn—descended from Amlaíb Cúarán, King of Northumbria and Dublin.[45] Another family was that of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, a man whose parentage is uncertain.[46] Whilst Echmarcach's family forged an alliance with the Uí Briain kindred,[47] Diarmait—a bitter opponent of both Echmarcach and Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster—appears to have cooperated with the descendants of Amlaíb Cúarán.[48] In consequence, there are important implications in regard to Gofraid mac Sitriuc's familial identification.

As a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán

[edit]In 1066, Haraldr Sigurðarson, King of Norway embarked upon an ill-fated invasion of England. Unfortunately for the Norwegians, their forces were utterly destroyed by the English in the subsequent Battle of Stamford Bridge.[49] It was in the aftermath of this defeat that the Chronicle of Mann first makes note of Gofraid mac Sitriuc, and his ultimate successor, Gofraid Crobán. Specifically, this source states that, following the latter's flight from the slaughter at Stamford, Gofraid mac Sitriuc honourably received him, and granted him sanctuary.[50] If Gofraid mac Sitriuc was indeed a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán, his generosity towards Gofraid Crobán may have been conducted in the context of interfamily fellowship, since the latter could have been a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán as well.[51] In fact, Gofraid mac Sitriuc's apparent descent from Amlaíb Cúarán would also explain the circumstances surrounding his accession to the kingship of the Isles.[14] For instance, only five years previously Diarmait's son appears to have overcome Echmarcach on Mann.[52] The unlikelihood that Diarmait would have allowed a member of Echmarcach's family to continue to reign in the Isles suggests that Diarmait may have installed a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán—in this case Gofraid mac Sitriuc—as his client in the Isles.[14] Diarmait may have done exactly that in Dublin decades before when he expelled Echmarcach from Dublin in 1052, and possibly installed Ímar mac Arailt in his place as King of Dublin.[53] The latter seems to have been not only a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán,[14] but also Gofraid Crobán's father,[54] uncle,[55] or brother.[56]

According to the Chronicle of Mann, Gofraid mac Sitriuc died in about 1070, and was succeeded by his son, Fingal,[58] a man who may have ruled for as long as nine years.[59] In 1073, a year after Toirdelbach's seizure of Dublin, Fingal evidently repulsed an Irish-based invasion of Mann.[60] The incursion is recorded by the Annals of Loch Cé[61] and the Annals of Ulster, the latter of which states that the expedition was led by a certain Sigtryggr Óláfsson and two grandsons of Brian Bóruma, High King of Ireland.[62] The precise identity of these three slain raiders is uncertain, as are the circumstances of the expedition itself.[63] It is very likely, however, that the incursion was closely connected to the Uí Briain takeover of Dublin in the wake of Diarmait's death the year before.[64] There is reason to suspect that Sigtryggr was a member of Echmarcach's family, perhaps a brother of Gofraid ua Ragnaill himself.[65] It is further possible that this family also included Donnchad's wife, Cacht ingen Ragnaill.[66] Certainly, Echmarcach's daughter, Mór, married Toirdelbach's son, Tadc.[47] If the Uí Briain were indeed bound to a kindred comprising Gofraid mac Sitriuc, Sigtryggr, Cacht, and Echmarcach, it is possible that—following the Dublin ascendancy of the Uí Briain—Sigtryggr and his Uí Briain allies attempted to take what they regarded as his family's patrimony in the Isles.[67]

As a kinsman of Echmarcach

[edit]If Gofraid mac Sitriuc is instead identical to Gofraid ua Ragnaill, and thus an apparent member of Echmarcach's family, it could mean that Gofraid ua Ragnaill had succeeded Echmarcach in Dublin and the Isles.[68] This identification could mean that Sigtryggr—slain in the ill-fated invasion of Mann in 1073—was a descendant of Amlaíb Cúarán rather than a member of Echmarcach's family.[69][note 5] In any case, numerous Irish annals report that two years after the assault on Mann, Gofraid ua Ragnaill's reign and life came to an end,[70] with the Annals of Inisfallen recording that Toirdelbach banished Gofraid ua Ragnaill from Dublin altogether, and further stating that he died "beyond the sea", having assembled a "great fleet" to come to Ireland.[71] If Gofraid mac Sitriuc and Gofraid ua Ragnaill are indeed identical, this annal-entry could be evidence that Toirdelbach ousted Gofraid ua Ragnaill from Dublin after failing to force him from Mann. If correct, this annal-entry could also be evidence that Gofraid ua Ragnaill fell back to Mann after his expulsion from Dublin, and attempted to assemble a fleet of Islesmen there before his death.[72]

Fingal and Gofraid Crobán

[edit]| Simplified family tree illustrating possible lines of shared ancestry between Gofraid mac Sitriuc and Gofraid Crobán if both men were descendants of Amlaíb Cúarán. Possible fathers of Gofraid mac Sitriuc are coloured turquoise, whilst a possible father of Gofraid Crobán is coloured pink. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In about 1075,[74] or 1079,[75] the Chronicle of Mann reveals that Gofraid Crobán succeeded in conquering Mann following three sea-borne invasions.[76] The circumstances surrounding this conquest are obscure.[77] On one hand, it is possible that he overthrew Fingal,[78] who may have been weakened by the invasion of 1073.[79] On the other hand, the amiable relations between Gofraid Crobán and Fingal's father could suggest that, as long as Fingal lived his kingship was secure, and that it was only after his death that Gofraid Crobán attempted seize control.[59] The chronicle only mentions Fingal once—in the context of succeeding his father—and he is not recorded in any other source.[80]

If Gofraid mac Sitriuc and Gofraid ua Ragnaill are indeed the same individual, the record of the latter's death in 1075 could have bearing on Gofraid Crobán's coup.[77] Specifically, the latter gained the kingship of the Isles at about this time, and the chronicle places his campaigns in the context of combating the Manx themselves, making no mention of Fingal or a king at all during these conflicts.[81] Gofraid Crobán, therefore, may have made his move whilst the kingship was vacant.[77][note 6]

Despite the disappearance of Fingal from the historical record, there may be evidence that his descendants ruled in parts of Galloway.[82] Specifically, in 1094, the Annals of Inisfallen records the death of a certain King of the Rhinns named "Macc Congail".[83] On one hand, this could be evidence that Fingal's name was actually Congal.[84] On the other hand, "Macc Congail" may simply represent the source's confusion between the names Fingal and Congal. In fact, the record of Echmarcach reigning as "rex Innarenn" could be evidence that Echmarcach had formerly ruled this particular region. In any case, it is unknown if Macc Congail was independent from, or dependent upon, Gofraid Crobán's authority.[59][note 7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since the 2000s, academics have accorded these men various names in English secondary sources: For example, Fingal has been accorded the personal names: Fingal,[2] and Finghal.[3] Gofraid mac Sitriuc has likewise been accorded the following personal names: Godred,[4] Gofraid,[5] and Guðrøðr.[6] Furthermore, these men have been accorded the following patronymic names: Fingal Godredsson,[7] Fingal mac Gofraid,[8] Finghal mac Gofraid,[3] Godred Sigtrygsson,[9] Godred Sitricsson,[7] Gofraid mac Sitreaca,[3] and Gofraid mac Sitriuc.[10]

- ^ The Norse-Gaelic territory of Fine Gall has left its name on the county of Fingal. The name Fine Gall means "kindred of the foreigners",[16] or "territory of the foreigners".[17] The modern personal name Fingal is derived from the Gaelic Fionnghall. This name is composed of the elements fionn ("white") and gall ("stranger"), and was originally a byname accorded to Norse settlers like the comparable personal name Dubhghall (from elements meaning "dark" and "stranger").[18] See also: Dubgaill and Finngaill.

- ^ This Sitriuc mac Glún Iairn may be identical to the unnamed man who killed Sitriuc mac Amlaíb's slain son, Gofraid, in 1036.[23] Another possibility is that the slayer was instead the son of another like-named man, Járnkné Óláfsson.[24]

- ^ The mediaeval Kingdom of the Rhinns may have included, not only the Rhinns of Galloway, but also the Machars as well. The kingdom appears to have stretched from the North Channel to Wigtown Bay, and would have likely encompassed an area similar to the modern boundaries of Wigtownshire.[40]

- ^ If this identification is correct, Sigtryggr may have been a son of Amlaíb, son of Sitriuc mac Amlaíb.[69]

- ^ In the three encounters, the chronicle specifically states that Gofraid Crobán fought "cum populo terre" ("with the people of the land"), and "cum Mannensibus" ("with the "Manxmen"), and "Mannenses" ("the Manxmen").[81]

- ^ Macc Congail is the last recorded King of the Rhinns. By the early twelfth century, the region appears to have formed part of the Gallovidian territory controlled by the family of Fergus, Lord of Galloway.[85]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Munch; Goss (1874) p. 50; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Duffy (2006); Beuermann (2002); Oram (2000); Candon (1988).

- ^ a b c Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005).

- ^ Fuller (2009); Duffy (2006); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Beuermann (2002); Oram (2000); Candon (1988).

- ^ Duffy (2006); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Woolf (2004); Oram (2000).

- ^ Duffy (2006).

- ^ a b Moody; Martin; Byrne (2005).

- ^ Oram (2000).

- ^ Fuller (2009).

- ^ Woolf (2004); Oram (2000).

- ^ a b Duffy (2006) pp. 51–52; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 232 n. 40; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Duffy (2006) pp. 51–52; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Duffy (2006) p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171.

- ^ Duffy (2017); Downham (2014) p. 19; Downham (2013) p. 158; Downham (2005); Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171; Valante (1998–1999) p. 246, 246 n. 16; Holm (2000) pp. 254–255.

- ^ Woolf (2018) p. 126; Downham (2014) p. 19; Downham (2013) p. 158; Downham (2005).

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 158; Duffy (2009) p. 291.

- ^ Hanks; Hardcastle; Hodges (2006) pp. 402, 403.

- ^ a b Duffy (2006) p. 52; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 52; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 231; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 83 fig. 3, 171; Oram (2000) p. 18.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 52; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 83 fig. 3, 171.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 83 fig. 3, 171–172; Bugge (1905) pp. 4, 11.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 83 fig. 3, 121, 171–172; Etchingham (2001) p. 158 n. 35; Hudson, B (1994a) p. 329.

- ^ Etchingham (2001) p. 158 n. 35.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 57; Moody; Martin; Byrne (2005) p. 468 n. 3; Beuermann (2002) p. 433; Candon (1988) p. 402.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1072.6; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1072.6; Duffy (2006) p. 57; Duffy (1992) p. 102.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1075.2; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1075.2; Duffy (2006) p. 57; Duffy (1992) p. 102 n. 44.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1075.1; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1075.1; Duffy (2006) p. 57; Duffy (1992) p. 102 n. 44.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4.

- ^ a b c d Duffy (2006) p. 57.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 57; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 130 fig. 4; Duffy (1992) p. 102.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2004); Duffy (1992) p. 94.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 129; Hudson, BT (2004); Duffy (1992) p. 100.

- ^ Downham (2007) p. 193 fig. 12; Duffy (2006) p. 57.

- ^ Clancy (2008) p. 28; Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 57; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 129, 130 fig. 4.

- ^ Flanagan (2010) p. 231 n. 196; Clancy (2008) p. 28; Downham (2007) p. 171; Duffy (2006) p. 56–57; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 229; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 129, 138; Etchingham (2001) p. 160; Oram (2000) p. 17; Duffy (1992) pp. 98–99; Anderson (1922a) pp. 590–592 n. 2; Waitz (1844) p. 559.

- ^ Flanagan (2010) p. 231 n. 196; Duffy (2006) pp. 56–57.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 107; Flanagan (2010) p. 231 n. 196; Clancy (2008) p. 28; Downham (2007) p. 171; Duffy (2006) pp. 56–57; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 229; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 129, 138; Etchingham (2001) p. 160; Oram (2000) p. 17; Duffy (1992) pp. 98–99.

- ^ Woolf (2007) p. 245; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 143; Duffy (1992) p. 100.

- ^ Clancy (2008) pp. 28, 32; Woolf (2007) p. 245; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 138.

- ^ Duffy (1993b) p. 13.

- ^ Bracken (2004); Duffy (1992) p. 101.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Oram (2000) p. 18.

- ^ Duffy (1992) p. 102.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 83 fig 3.

- ^ Woolf (2007) p. 246.

- ^ a b Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Duffy (1992) p. 105, 105 n. 59.

- ^ Duffy (1992) pp. 96–97.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 210–211; Anderson (1922b) pp. 13–15 n. 3.

- ^ Fuller (2009); Byrne (2008) p. 864; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171; Woolf (2004) p. 100; Anderson (1922b) p. 18 n. 1, 43–44 n. 6; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–51.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 170–171; Woolf (2004) p. 100.

- ^ Duffy (2006) pp. 55–56; Hudson, B (2005a); Hudson, BT (2005) p. 171; Hudson, BT (2004); Duffy (1992) p. 100.

- ^ Duffy (1992) p. 97.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 22, 27 n. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 62, 62 n. 18; Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 60; Hudson, B (2006) p. 170; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 54, 83 fig. 3, 171; Duffy (2004); Woolf (2004) p. 100; Duffy (1992) p. 106.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 22, 27 n. 4; McDonald (2007b) p. 62 n. 18; Duffy (2004); Duffy (1992) p. 106.

- ^ Woolf (2004) p. 100.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1073.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1073.5; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489 (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2007) pp. 61–62; Duffy (2006) p. 51; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Woolf (2004) p. 100; Byrne (1982); Anderson (1922b) p. 22; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172.

- ^ Duffy (2006) pp. 57–58; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Woolf (2004) pp. 100–100; Oram (2000) p. 19.

- ^ Annals of Loch Cé (2008) § 1073.3; Annals of Loch Cé (2005) § 1073.3; Duffy (1993a) p. 33; Candon (1988) p. 403.

- ^ Downham (2017) p. 100; The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1073.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1073.5; Duffy (2006) pp. 57–58; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, B (2005b); Ní Mhaonaigh (1995) p. 375; Duffy (1993a) p. 33; Candon (1988) p. 403.

- ^ Duffy (1993a) p. 33; Duffy (1992) p. 102.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 57; Candon (2006) p. 116; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Ní Mhaonaigh (1995) p. 375; Duffy (1993a) p. 33; Duffy (1992) p. 102; Candon (1988) p. 403.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, B (2005b); Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 130 fig. 4, 172; Oram (2000) pp. 18–19.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 130 fig. 4; Oram (2000) pp. 18–19.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 57; Candon (1988) p. 402.

- ^ a b Duffy (2006) pp. 53, 57–58.

- ^ Chronicon Scotorum (2012) § 1075; The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1075.1; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1075.2; Chronicon Scotorum (2010) § 1075; The Annals of Tigernach (2010) § 1075.2; Duffy (2009) pp. 295–296; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1075.2; Annals of Loch Cé (2008) § 1075.1; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1075.1; Duffy (2006) p. 58; Annals of Loch Cé (2005) § 1075.1; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1075.2; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 167; Hudson, B (1994b) p. 152, 152 n. 41; Duffy (1992) p. 102; Candon (1988) p. 399; Richter (1985) p. 336.

- ^ Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1075.2; Duffy (2009) pp. 295–296; Duffy (2006) p. 58; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 167; Hudson, B (1994b) p. 152, 152 n. 41; Duffy (1992) p. 102; Candon (1988) p. 399; Richter (1985) p. 336.

- ^ Duffy (2006) p. 58.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 108; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1094.5; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503 (n.d.).

- ^ Flanagan (2008) p. 907; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Oram (2000) p. 19.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 11, 48; Flanagan (2008) p. 907; Duffy (2006) pp. 61–62; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Woolf (2004) pp. 100–101.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 46, 48; McDonald (2007) p. 61; Duffy (2006) pp. 61–62; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; McDonald (1997) pp. 33–34; Anderson (1922b) pp. 43–45; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–53.

- ^ a b c Duffy (2006) p. 62.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Woolf (2004) pp. 100–101.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Oram (2000) p. 19.

- ^ Duffy (2006) pp. 51, 58; Anderson (1922b) p. 22; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–53.

- ^ a b Duffy (2006) p. 62; Anderson (1922b) pp. 43–45; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 50–53.

- ^ Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Byrne (1982).

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 108; Annals of Inisfallen (2010) § 1094.5; Annals of Inisfallen (2008) § 1094.5; Hudson, BT (2005) p. 172; Moody; Martin; Byrne (2005) p. 468 n. 4; Beuermann (2002) p. 433; Duffy (1992) p. 99 n. 32; Candon (1988) p. 402; Byrne (1982).

- ^ Moody; Martin; Byrne (2005) p. 468 n. 4.

- ^ McGuigan (2015) p. 108.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922a). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. OL 14712679M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922b). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 2. London: Oliver and Boyd.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (23 October 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 February 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Annals of Loch Cé". Corpus of Electronic Texts (5 September 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 489". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 503". Early Manuscripts at Oxford University. Oxford Digital Library. n.d. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Bugge, A, ed. (1905). On the Fomorians and the Norsemen. Oslo: J. Chr. Gundersens Bogtrykkeri. OL 7129118M.

- "Cotton MS Julius A VII". British Library. n.d. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 March 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (14 May 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Munch, PA; Goss, A, eds. (1874). Chronica Regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: The Chronicle of Man and the Sudreys. Vol. 1. Douglas, IM: Manx Society.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (2 November 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Waitz, G (1844). "Mariani Scotti Chronicon". In Pertz, GH (ed.). Monvmenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores. Hanover: Hahn. pp. 481–568.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Beuermann, I (2002). "Metropolitan Ambitions and Politics: Kells-Mellifont and Man & the Isles". Peritia. 16: 419–434. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.497. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Bracken, D (2004). "Ua Briain, Toirdelbach [Turlough O'Brien] (1009–1086)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20468. Retrieved 25 November 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Byrne, FJ (1982). "Onomastica 2". Peritia. 1: 267. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.615. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Byrne, FJ (2008) [2005]. "Ireland and Her Neighbours, c.1014–c.1072". In Ó Cróinín, D (ed.). Prehistoric and Early Ireland. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 862–898. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Candon, A (1988). "Muirchertach Ua Briain, Politics and Naval Activity in the Irish Sea, 1075 to 1119". In Mac Niocaill, G; Wallace, PF (eds.). Keimelia: Studies in Medieval Archaeology and History in Memory of Tom Delaney. Galway: Galway University Press. pp. 397–416.

- Candon, A (2006). "Power, Politics and Polygamy: Women and Marriage in Late Pre-Norman Ireland". In Bracken, D; Ó Riain-Raedel, D (eds.). Ireland and Europe in the Twelfth Century: Reform and Renewal. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 106–127. ISBN 978-1-85182-848-7.

- Clancy, TO (2008). "The Gall-Ghàidheil and Galloway" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 2: 19–51. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Downham, C (2005). "Fine Gall". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Downham, C (2013). "Living on the Edge: Scandinavian Dublin in the Twelfth Century". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 157–178. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Downham, C (2014). "Vikings' Settlements in Ireland Before 1014". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Downham, C (2017). "Scottish Affairs and the Political Context of Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh". Traversing the Inner Seas: Contacts and Continuity Around Western Scotland, the Hebrides and Northern Ireland. Edinburgh: Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 86–106. ISBN 978-1-5272-0584-0.

- Duffy, S (1992). "Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052–1171". Ériu. 43: 93–133. eISSN 2009-0056. ISSN 0332-0758. JSTOR 30007421.

- Duffy, S (1993a). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin. hdl:2262/77137.

- Duffy, S (1993b). "Pre-Norman Dublin: Capital of Ireland?". History Ireland. 1 (4): 13–18. ISSN 0791-8224. JSTOR 27724114.

- Duffy, S (2004). "Godred Crovan (d. 1095)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50613. Retrieved 5 July 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Duffy, S (2006). "The Royal Dynasties of Dublin and the Isles in the Eleventh Century". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. Vol. 7. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 51–65. ISBN 1-85182-974-1.

- Duffy, S (2009). "Ireland, c.1000–c.1100". In Stafford, P (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500–c.1100. Blackwell Companions to British History. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 285–302. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3.

- Duffy, S (2013). Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-5778-5.

- Duffy, S (2017). "Dublin". In Echard, S; Rouse, R (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118396957.wbemlb509. ISBN 9781118396957.

- Etchingham, C (2001). "North Wales, Ireland and the Isles: the Insular Viking Zone". Peritia. 15: 145–187. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.434. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Flanagan, MT (2008) [2005]. "High-Kings With Opposition, 1072–1166". In Ó Cróinín, D (ed.). Prehistoric and Early Ireland. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 899–933. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Flanagan, MT (2010). The Transformation of the Irish Church in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-597-4. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Fuller, MC (2009). "Where was Iceland in 1600?". In Singh, JG (ed.). A Companion to the Global Renaissance: English Literature and Culture in the Era of Expansion. Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 149–162. doi:10.1002/9781444310986.ch8. ISBN 978-1-405-15476-5.

- Hanks, P; Hardcastle, K; Hodges, F (2006) [1990]. A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford Paperback Reference (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861060-1.

- Holm, P (2000). "Viking Dublin and the City-State Concept: Parameters and Significance of the Hiberno-Norse Settlement". In Hansen, MH (ed.). A Comparative Study of Thiry City-State Cultures. Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter. Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. pp. 251–262. ISBN 87-7876-177-8. ISSN 0023-3307.

- Hudson, B (1994a). "Knútr and Viking Dublin". Scandinavian Studies. 66 (3): 319–335. eISSN 2163-8195. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919663.

- Hudson, B (1994b). "William the Conqueror and Ireland". Irish Historical Studies. 29 (114): 145–158. doi:10.1017/S0021121400011548. eISSN 2056-4139. ISSN 0021-1214. JSTOR 30006739.

- Hudson, B (2005a). "Diarmait mac Máele-na-mBó (Reigned 1036–1072)". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 127–128. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Hudson, B (2005b). "Ua Briain, Tairrdelbach, (c. 1009–July 14, 1086 at Kincora)". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 462–463. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Hudson, B (2006). Irish Sea Studies, 900–1200. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-983-5.

- Hudson, BT (2004). "Diarmait mac Máel na mBó (d. 1072)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50102. Retrieved 2 June 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hudson, BT (2005). Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516237-0.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007). Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McDonald, RA (2019). Kings, Usurpers, and Concubines in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22026-6. ISBN 978-3-030-22026-6.

- McGuigan, N (2015). Neither Scotland nor England: Middle Britain, c.850–1150 (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7829.

- Moody, TW; Martin, FX; Byrne, FJ, eds. (2005). Maps, Genealogies, Lists: A Companion to Irish History. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821745-9.

- Ní Mhaonaigh, M (1995). "Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib: Some Dating Considerations". Peritia. 9: 354–377. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.255. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Oram, RD (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-541-5.

- Richter, M (1985). "The European Dimension of Irish History in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries". Peritia. 4: 328–345. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.113. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Valante, MA (1998–1999). "Taxation, Tolls and Tribute: The Language of Economics and Trade in Viking-Age Ireland". Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. 18–19: 242–258. ISSN 1545-0155. JSTOR 20557344.

- Woolf, A (2004). "The Age of Sea-Kings, 900–1300". In Omand, D (ed.). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 94–109. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Woolf, A (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

- Woolf, A (2018). "The Scandinavian Intervention". In Smith, B (ed.). The Cambridge History of Ireland. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–130. doi:10.1017/9781316275399.008. ISBN 978-1-107-11067-0.