Fabrizio De André

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Fabrizio De André | |

|---|---|

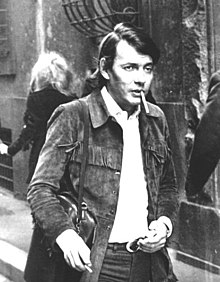

De André in 1971 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Fabrizio Cristiano De André |

| Born | 18 February 1940 Genoa, Italy |

| Died | 11 January 1999 (aged 58) Milan, Italy |

| Genres | |

| Occupation | Singer-songwriter |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1958–1999 |

| Labels | |

| Website | fondazionedeandre.it |

Fabrizio Cristiano De André (Italian: [faˈbrittsjo de anˈdre]; 18 February 1940 – 11 January 1999) was an Italian singer-songwriter and the most-prominent cantautore of his time. He is also known as Faber, a nickname given by the friend Paolo Villaggio, as a reference to his liking towards Faber-Castell's pastels and pencils, aside from the assonance with his own name,[1] and also because he was known as "il cantautore degli emarginati" or "il poeta degli sconfitti".[2][3] His 40-year career reflects his interests in concept albums, literature, poetry, political protest, and French music.[4] He is considered a prominent member of the Genoese School. Because of the success of his music in Italy and its impact on the Italian collective memory, many public places such as roads, squares, and schools in Italy are named after De André.[5]

Biography

[edit]

Fabrizio De André was born in Pegli, Genoa, Italy, to an upper-class family. He had a warm, deep voice,[6] and started playing guitar at the age of 14.[7] His father gave him some Georges Brassens records, whose songs influenced the style of his first songs.[8] Brassens also inspired De André to become a libertarian and a pacifist,[9] which was influential in his music and later, more-sophisticated productions.

1960s

[edit]When he was a student in February 1961, De André debuted, singing two songs in a theater in Genoa.[10] The two songs were later recorded as his first single, "Nuvole barocche" b/w "E fu la notte", which was released in 1961 and was an imitation of Domenico Modugno.[11] In his following recordings in the early 1960s, De André found a more personal style, mixing literature with traditional songs (in particular Medieval ones), presenting himself as a contemporary troubador and storyteller. His narrative centered on the stories of marginalized people and antiheroes. He later recorded protest songs such as La ballata del Miché ("Mickey's Ballad"), which he co-wrote with his friend Clelia Petracchi;[12] La Guerra di Piero ("Piero's War"), an anti-war song, with contributions from Vittorio Centenaro and others. Some of the songs were inspired by his city, Genoa, such as La Città Vecchia ("The old (side of the) city"), which he co-wrote with Elvio Monti; and Via del Campo, with the music of Enzo Jannacci. He also wrote two songs with his life-long friend Paolo Villaggio, Il Fannullone and Carlo Martello (ritorna dalla battaglia di Poitiers) ("Charles Martel Returns from the Battle of Poitiers"), in 1963.[13]

In 1962, his first son Cristiano De André was born to his first wife Enrica "Puny" Rignon, who he married in the same year.[14]

His first song to find commercial success was La canzone di Marinella ("The song of Marinella") in 1967, thanks to a television performance by Mina.[15] Following this first success, his first album of new songs was released in 1967 with the title Volume 1. The album opens with "Preghiera in Gennaio" ("Prayer in January"), which is dedicated to De André's friend Luigi Tenco, a singer-songwriter who committed suicide before the album's release during his participation in the Sanremo Festival.[16] Despite the popularity of this festival, De André refused to participate in any song competition by principle, and rarely appeared on television. In 1966, De André's first compilation Tutto Fabrizio De André was released.

In 1968, De André released Tutti morimmo a stento, a concept album sung in Italian, with orchestral arrangements of Gian Piero Reverberi—a first for De André. The lyrics of the first song Il Cantico dei Drogati ("Junkies' Canticle") were co-written with poet Riccardo Mannerini, one of the most-significant persons in De André's life.[17] De André and Mannerini also co-wrote lyrics for the 1968 album of the band New Trolls, Senza orario Senza bandiera. In 1969, it was released the album Volume 3; due to their lyrics, some of its songs were censored by the national Italian television channel but were broadcast by Vatican Radio.[18]

1970s

[edit]

In 1970 the song Il pescatore ("The Fisherman") was released. The same year, it was released La buona novella (The Good News), another concept album that was inspired by the life of Jesus Christ as reported mainly by the Apocryphal gospels. The album was followed in 1971 by Non al denaro non all'amore né al cielo which was inspired by the Spoon River Anthology, a collection of short poems from Edgar Lee Masters, with the collaboration of Nicola Piovani for the music and Giuseppe Bentivoglio for the lyrics. The album's booklet contains an interview from Fernanda Pivano, the Italian translator of Masters' works. In 1973, De André wrote the concept album Storia di un impiegato, which is about the protests of those years, also involving Piovani and Bentivoglio. In 1974, he released the album Canzoni, which includes re-recordings of many old songs and new translations of songs of Brassens, Leonard Cohen ("Suzanne" and "Joan of Arc"), and Bob Dylan ("Desolation Row"), thanks to the collaboration of Francesco De Gregori. In 1975, the experimental (both musically and linguistically[19]) album Volume/8 was a collaboration with the songwriter Francesco De Gregori, and includes a translation of a song by Leonard Cohen ("Seems so long ago, Nancy").

In 1975, De André made his concert debut at "La Bussola" in Viareggio.[20] Before that event, De André refused to perform live concerts because he considered himself more a songwriter than a performer.[21] In the same period, he moved from Genoa to Sardinia. In 1978, his new concept album Rimini, which he co-wrote with singer-songwriter Massimo Bubola was released; it includes a translation of Bob Dylan's "Romance in Durango" (Avventura a Durango). For the first time, he wrote a song in Gallurese, a local language related to Corsican, Zirichiltaggia ("Lizard Den"), inspired by the Ballu tundu, beginning to show his passion for minority languages and music traditions.

In 1977, his daughter Ludovica Vittoria (nicknamed simply Luvi) was born to his partner Dori Ghezzi.[22] Between December 1978 and January 1979, De André toured with the Italian progressive rock band Premiata Forneria Marconi (PFM), from which two live albums (In Concerto - Arrangiamenti PFM, vol. 1 and 2) were released. Many years later, in 2020, a video taken from that tour was discovered and published as a DVD with the title "Fabrizio De André e PFM - Il concerto ritrovato".

On 27 August 1979, De André and Dori Ghezzi were kidnapped in Sardinia.[23] They were released only in December.

1980s

[edit]

Together with Sergio Bardotti De André translated the song "Famous Blue Raincoat" with the title La Famosa Volpe Azzurra, which was performed by Ornella Vanoni on her album Ricetta di donna (1980).[24]

In 1981, De André and Massimo Bubola released the single Una storia sbagliata, which was dedicated to Pier Paolo Pasolini and appeared as an opening theme to an Italian television program. Later in 1981, De André released an album without a title, also known as L'Indiano (The Indian) due to the cover reproducing the painting The Outlier by Frederic Remington. The album is more inspired by rock music than De André's earlier ones, partly because of the collaboration in songwriting with Bubola. The arrangements were done by the American-born musician Mark Harris, who also sings Ave Maria in Sardinian. The track Hotel Supramonte was inspired by the De André's kidnapping experience.[25] In 1982, De André, who disliked traveling, went on his first and only European tour of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland.[26] In 1984, Joan Baez sang "Marinella" during an Italian television program.[27]

In 1984 the album Crêuza de mä was released, a collaboration with the multi-instrumentalist Mauro Pagani, a former member of PFM. This album is very unusual: its music was inspired by the Mediterranean music played with instruments from many local traditions, resulting in a special kind of world music and entirely sung in Genoese. David Byrne, later talking to Rolling Stone, named the album as one of the most-important releases of the decade.[28] In 1985, De André co-wrote the song Faccia di Cane however unofficially, which was performed by the New Trolls at the Sanremo Music Festival 1985, where it placed third and won the Prize of the Critic.[29] In 1988 De André sung in the song "Questi posti davanti al mare" together with Francesco De Gregori and Ivano Fossati, who also wrote the song, included in Fossati's 1988 album La pianta del tè.

In 1985, De André promised his dying father to stop his abuse of alcohol[30] but he continued to be a heavy smoker. In 1989, De André married Dori Ghezzi.[31] Their marriage testimony was the actor and long-life friend Beppe Grillo.[32] In the same year, Fabrizio's brother Mauro, a corporate lawyer, who also helped Fabrizio with his career, died.

1990s

[edit]In 1990 De André released Le nuvole, a collaboration with Pagani. The album was arranged by Piero Milesi. The first half of the album (side A) is sung in Italian while the second half (side B) is sung in Sardinian, Genoese, and Neapolitan. The album is also credited to Francesco Baccini for some verses of the song Ottocento; Baccini later recorded a duet with De André named Genova Blues. In 1991, De André toured released the double live album 1991 Concerti.

In these years, De André collaborated also with other duets in Italian: Navigare with Ricky Gianco (1992) and La Fiera della Maddalena with Max Mandredi (1994).

De André also collaborated with the band Tazenda, singing a song in Sardinian (Etta Abba Chelu) and co-writing the song Pitzinnos in sa gherra ("Children in the War"), both of which were included on their 1992 album Limba.[33] He sang in Old Occitan with the band Troubaires de Coumboscuro (Mis Amour) in 1995.[34] In 1994, he performed the song Cielito Lindo in Spanish as an opening theme for an Italian television show of the same name.[35]

In 1996 he released his last album Anime Salve, a concept album about solitude, in collaboration with Ivano Fossati. The arrangements are by Milesi. Fossati also duets with De André on two of the songs, the tile track and  cùmba. The first song on the album, Prinçesa, is inspired by the autobiography of the transsexual Fernanda Farias De Albuquerque.[36] This song was awarded the Targa Tenco as Song of the Year.[37] The last song of the album Smisurata preghiera summarizes the work of writer Álvaro Mutis; De André also released a Portuguese version of the song titled Desmedida plegaria, which was included in the score of the film Ilona Arrives with the Rain. The song was awarded the Lunezia Prize.

Also in 1996, De André co-wrote his only novel Un destino ridicolo with writer Alessandro Gennari; in 2008, this novel inspired the film Amore che vieni, amore che vai. In 1997, he recorded a new version of Marinella, this time as a duo with Mina, which is included in the compilation Mi innamoravo di tutto. During the period 1997–1998, De André went on the longest tour of his career, playing in arenas, open spaces, and theaters. Some of the summer dates were opened by poet and songwriter Oliviero Malaspina, with whom he was planning a collaboration for his next studio album.[38] This long tour had to be interrupted because of the first signs of health problems. He was subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer.[39]

Fabrizio De André died in Milan on 11 January 1999. Two days later, a public funeral took place in the Basilique of Santa Maria Assunta in Carignano, Genoa, in front of a large audience.[40] De André was buried in the family chapel in the Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno.

Discography

[edit]

Albums[edit]

Compilations[edit]

Live albums[edit]

Tributes[edit]

|

Singles[edit]

Box-sets[edit]

|

Videography

[edit]Music videos

[edit]- La domenica delle salme (1990) – directed by Gabriele Salvatores

- Mégu megún (1990) – directed by Gabriele Salvatores, starring: Claudio Bisio[42]

- Ho visto Nina volare (1997) – directed by Pietro Follini

Concerts

[edit]- Fabrizio De André in Concerto (2004)

- Fabrizio De André e PFM - Il concerto ritrovato (2020)

Documentaries

[edit]- Effedia: Sulla mia cattiva strada (2008)

- Dentro Faber (2011) (8 DVDs on different subjects each)

- Faber in Sardegna & L'ultimo concerto di Fabrizio De André, directed by Gianfranco Cabiddu, 2015

Tributes

[edit]- Omaggio a Fabrizio De André (2006) (tribute concert performed in the Roman Amphitheatre of Cagliari on 10 July 2005)

- PFM canta De André (2008)

Inspired movies

[edit]- Amore che vieni, amore che vai (2008) – directed by Daniele Costantini

- Fabrizio De André - Principe libero (2018) – directed by Luca Facchini

Novels

[edit]- De André, Fabrizio (1996). Un destino ridicolo. with Alessandro Gennari. Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-17591-2.

Diaries

[edit]- De André, Fabrizio (2018). Sotto le ciglia chissà (in Italian). Mondadori. ISBN 9788804675877.

Interviews

[edit]- Franchini, Alfredo (2014). Uomini e donne di Fabrizio De André: conversazioni ai margini (in Italian). Fratelli Frilli Editori. ISBN 978-8875631604.

- Sassi, Claudio; Pistarini, Walter; Ceri, Luciano, eds. (2008). De Andre talk: Le interviste e gli articoli della stampa d'epoca (in Italian). Coniglio. ISBN 978-8860631534.

Biographies

[edit]- Romana, Cesare G. (1991). Amico fragile (in Italian). Sperling & Kupfer. ISBN 8820012146.

- Viva, Luigi (2000). Non per un dio ma nemmeno per gioco: Vita di Fabrizio De André (in Italian) (1st ed.). Feltrinelli Editore. ISBN 9788807815805.

- De André, Fabrizio (2007). Guido Harari (ed.). Una goccia di splendore. Un'autobiografia per parole e immagini, con testi inediti (in Italian). Milano: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-88-17-01166-2.

Essayes

[edit]- Fondazione Fabrizio De André, Bruno Bigoni, Romano Giuffrida, Accordi eretici, La Nave di Teseo, 2021. ISBN 8893950928.

- Pistarini, Walter (2010). Il libro del Mondo - Fabrizio De André: le storie dietro le canzoni (in Italian). Giunti. ISBN 9788809748514.

- Zanetti, Franco; Sassi, Claudio (2019). Fabrizio De André in concerto (in Italian). Giunti. ISBN 9788809881389.

Photobooks

[edit]- Harari, Guido (2001). E poi, il futuro... (in Italian). Mondadori. ISBN 9788804497080.

Comics

[edit]- Algozzino, Sergio (2008). Ballata per Fabrizio De André (in Italian). Padova: Edizioni Becco Giallo. ISBN 978-8897555100.

- Biani, Mauro (2009). Come una specie di sorriso (in Italian). Viterbo: Stampa Alternativa.

- Milazzo, Ivo; Càlzia, Fabrizio (2010). Uomo Faber - biografia a fumetti di Fabrizio De André. Novara: De Agostini.

References

[edit]- ^ Bertoncelli, Riccardo. Belin, sei sicuro? [Belin, are you sure about that?] (in Italian). p. 44.

- ^ Redazione (11 October 2009). "Fabrizio de André: il poeta cantautore dei perdenti e degli emarginati (di G.Aufiero)". Stato Quotidiano (in Italian). Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- ^ Franchini, Alfredo. Uomini e donne di Fabrizio De André. Conversazioni ai margini. Fratelli Frilli Editori. pp. cap. VII.

- ^ Haworth, Rachel (March 3, 2016). "Fabrizio De André and Georges Brassens". From the chanson française to the canzone d'autore in the 1960s and 1970s: Authenticity, Authority, Influence. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-317-13168-7.

- ^ "Intitolazioni" (in Italian).

- ^ Fabbri, Franco (2017). L'ascolto tabù (in Italian). Milano: Il Saggiatore. pp. 216–222.

- ^ Viva, p. 40.

- ^ Viva, p. 49.

- ^ Romana, p. 61.

- ^ Viva, p. 83.

- ^ Viva, p. 225.

- ^ Viva, p. 83.

- ^ Viva, p. 102.

- ^ Viva, p. 93.

- ^ Viva, p. 133.

- ^ Viva, p. 125.

- ^ Viva, p. 139.

- ^ Viva, p. 129.

- ^ Meacci, Giordano; Serafini, Francesca (15 November 2021). "Fabrizio De André (1974-1981)". Treccani (in Italian).

- ^ Viva, p. 164.

- ^ Viva, p. 103.

- ^ Viva, p. 172.

- ^ Viva, p. 179.

- ^ "Collaborazione: Autore" (in Italian).

- ^ Viva, p. 186.

- ^ Viva, p. 187.

- ^ De André, Fabrizio; Harari, Guido (2003). Harari, Guido (ed.). E poi, il futuro (in Italian). Mondadori. p. 124. ISBN 8804497084.

- ^ "Interview on mybestlife.com" (in Italian).

- ^ Giannotti, M. (2005). L'enciclopedia di Sanremo: 55 anni di storia del festival dalla A alla Z, Gremese: pag. 148.

- ^ Viva, p. 197.

- ^ Viva, p. 205.

- ^ Viva, p. 229.

- ^ "Tazenda" (in Italian).

- ^ "Troubaires" (in Italian).

- ^ Viva, p. 221.

- ^ Mediating the Human Body: Technology, Communication, and Fashion. (2003), Taylor & Francis.: p. 56.

- ^ Viva, p. 237.

- ^ Bertoncelli, Riccardo, ed. (2012). Belin, sei sicuro? Storia e canzoni - Con gli appunti inediti de I Notturni (in Italian). Giunti.

- ^ Viva, p. 244.

- ^ "Una folla silenziosa per Fabrizio De André". La Repubblica (in Italian). 13 January 1999.

- ^ (in Italian) Discography of Fabrizio De André Archived 25 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Affiora un video 'perduto' di Fabrizio De André" (in Italian). 13 September 2005.

Further reading

[edit]- Gilbert, Mark; Moneta, Sara Lamberti (2020). "De André, Fabrizio (1940–1999)". Historical Dictionary of Modern Italy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-5381-0254-1.

- Haworth, Rachel (2016). From the Chanson Française to the Canzone D'autore in the 1960s and 1970s: Authenticity, Authority, Influence. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1409441731.

- Fondazione Fabrizio De André (2021). Bruno Bigoni; Romano Giuffrida (eds.). Accordi Eretici (in Italian). La nave di Teseo. ISBN 9788893955881.

- Romana, Cesare G. (1991). Amico fragile (in Italian). Sperling & Kupfer. ISBN 8820012146.

- Pistarini, Walter (2010). Il libro del mondo. Le storie dietro le canzoni di Fabrizio De André (in Italian). Florence: Giunti. ISBN 978-88-09-74851-4.

- Zanetti, Franco; Sassi, Claudio (2008). Fabrizio De André in concerto (in Italian). Giunti Editore. ISBN 9788809062115.

External links

[edit]- Fabrizio De André at IMDb

- Ciabattoni, Francesco (2 March 2019). ""Fabrizio De André"". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 November 2022.