Zero-COVID

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Zero-COVID, also known as COVID-Zero and "Find, Test, Trace, Isolate, and Support" (FTTIS), was a public health policy implemented by some countries, especially China, during the COVID-19 pandemic.[1][a] In contrast to the "living with COVID-19" strategy, the zero-COVID strategy was purportedly one "of control and maximum suppression".[1] Public health measures used to implement the strategy included as contact tracing, mass testing, border quarantine, lockdowns, and mitigation software in order to stop community transmission of COVID-19 as soon as it was detected. The goal of the strategy was to get the area back to zero new infections and resume normal economic and social activities.[1][4]

A zero-COVID strategy consisted of two phases: an initial suppression phase in which the virus is eliminated locally using aggressive public health measures, and a sustained containment phase, in which normal economic and social activities resume and public health measures are used to contain new outbreaks before they spread widely.[4] This strategy was utilized to varying degrees by Australia, Bhutan,[5][6] Atlantic and Northern Canada,[7] mainland China, Hong Kong,[8] Macau,[9] Malaysia,[10] Montserrat, New Zealand, North Korea, Northern Ireland, Singapore, Scotland,[11] South Korea,[12] Taiwan,[13] Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tonga,[14] and Vietnam.[15][16] By late 2021, due to challenges with the increased transmissibility of the Delta and Omicron variants, and also the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines, many countries had phased out zero-COVID, with mainland China being the last major country to do so in December 2022.[17]

Experts have differentiated between zero-COVID, which was an elimination strategy, and mitigation strategies that attempted to lessen the effects of the virus on society, but which still tolerated some level of transmission within the community.[18][4] These initial strategies could be pursued sequentially or simultaneously during the acquired immunity phase through natural and vaccine-induced immunity.[19]

Advocates of zero-COVID pointed to the far lower death rates and higher economic growth in countries that pursued elimination during the first year of the pandemic (i.e., prior to widespread vaccination) compared with countries that pursued mitigation,[18] and argued that swift, strict measures to eliminate the virus allowed a faster return to normal life.[18] Opponents of zero-COVID argued that, similar to the challenges faced with the flu or the common cold, achieving the complete elimination of a respiratory virus like SARS-CoV-2 may not have been a realistic goal.[20] To achieve zero-COVID in an area with high infection rates, one review estimated that it would take three months of strict lockdown.[21]

Elimination vs. mitigation

[edit]

Epidemiologists have differentiated between two broad strategies for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic: mitigation and elimination.[4][22][23] Mitigation strategies (also commonly known as "flattening the curve") aimed to reduce the growth of an epidemic and to prevent the healthcare system from becoming overburdened, yet still accepted a level of ongoing viral transmission within the community.[4] By contrast, elimination strategies (commonly known as "zero-COVID") aimed to completely stop the spread of the virus within the community, which was seen as the optimal way to allow the resumption of normal social and economic activity.[4] In comparison with mitigation strategies, elimination involved stricter short-term measures to completely eliminate the virus, followed by milder long-term measures to prevent a return of the virus.[4][22]

After elimination of COVID-19 from a region, zero-COVID strategies required stricter border controls in order to prevent reintroduction of the virus, more rapid identification of new outbreaks, and better contact tracing to end new outbreaks.[22] Advocates of zero-COVID argued that the costs of these measures were lower than the economic and social costs of long-term social distancing measures and increased mortality incurred by mitigation strategies.[22][4]

The long-term "exit path" for both elimination and mitigation strategies depended on the development of effective vaccines and treatments for COVID-19.[22][4][24]

Containment measures

[edit]The zero-COVID approach aimed to prevent viral transmission using a number of different measures, including vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions such as contact tracing and quarantine. Successful containment or suppression reduced the basic reproduction number of the virus below the critical threshold.[23] Different combinations of measures were used during the initial containment phase, when the virus was first eliminated from a region; and the sustained containment phase, when the goal was to prevent reestablishment of viral transmission within the community.[25]

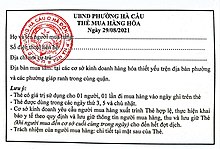

Lockdowns

[edit]Lockdowns encompassed measures such as closures of non-essential businesses, stay-at-home orders, and movement restrictions.[25] During lockdowns, governments were typically required to supply basic necessities to households.[25][4] Lockdown measures were commonly used to achieve initial containment of the virus.[25] In China, lockdowns of specific high-risk communities were also sometimes used to suppress new outbreaks.[4]

Quarantine for travelers

[edit]

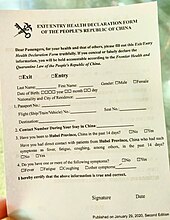

In order to prevent reintroduction of the virus into zero-COVID regions after initial containment had been achieved, quarantine for incoming travelers was commonly used. As each infected traveler could seed a new outbreak, the goal of travel quarantine was to intercept the largest possible percentage of infected travelers.[25][26]

International flights to China were heavily restricted, and incoming travelers were required to undergo PCR testing and quarantine in designated hotels and facilities.[27] In order to facilitate quarantine for travelers, China constructed specialized facilities at its busiest ports of entry, including Guangzhou and Xiamen.[25] New Zealand and Australia also established managed isolation and quarantine facilities for incoming travelers.[26]

Through November 2020, border quarantine measures prevented nearly 4,000 infected international travelers from entering the wider community within China.[28] Each month, hundreds of travelers who tested negative before flying to China subsequently tested positive while undergoing quarantine after arrival.[25]

Contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation

[edit]

Contact tracing involved identifying people who have been exposed to (or "came into close contact with") an infected person. Public health workers then isolated the known infected person and attempted to locate all of those exposed persons, and quarantine them until they either were unlikely to be infectious or received several negative tests. Various studies argued that early detection and isolation of infected people was the single most effective measure for preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2.[25][4] "Quarantine" referred to the separation of exposed persons who could have possibly been infected from the rest of society, while "isolation" referred to the separation of persons who were known to be infected.[29]

In China, when an infected person was identified, all close contacts were required to undergo a 14-day quarantine alongside multiple rounds of PCR testing.[28] In order to minimize the risk that these close contacts posed for outbreak containment, China implemented quarantine in centralized facilities for those deemed to be at the highest-risk of infection.[25] Secondary close contacts (contacts of close contacts) are sometimes required to quarantine at home.[25]

The widespread use of smartphones enabled more rapid "digital" contact tracing. In China, "health code" applications were used to facilitate the identification of close contacts, via analysis of Bluetooth logs which show proximity between devices.[4] Taiwan also made use of digital contact tracing, notably to locate close contacts of passengers who disembarked from the Diamond Princess cruise ship, the site of an early outbreak in February 2020.[30]

Routine testing of key populations

[edit]In China, routine PCR testing was carried out on all patients who present with fever or respiratory symptoms.[28] In addition, various categories of workers, such as medical staff and workers who handle imported goods, were regularly tested.[28]

In China, routine testing of key populations identified index patients in a number of outbreaks, including outbreaks in Beijing, Shanghai, Dalian, Qingdao, and Manchuria.[25] In some cases, index patients had been discovered while asymptomatic, limiting the amount of onward transmission into the community.[25]

Community-wide screening

[edit]An additional tool for identifying cases outside of known transmission chains was community-wide screening, in which populations of specific neighborhoods or cities were PCR tested. In China, community-wide PCR testing was carried out during outbreaks in order to identify infected people, including those without symptoms or known contact with infected people.[28] Community-wide screening was intended to rapidly isolate infected people from the general population, and to allow a quicker return to normal economic activity.[28] China first carried out community-wide screening from 14 May to 1 June 2020 in Wuhan, and used this technique in subsequent outbreaks.[28] In outbreaks in June 2020 in Beijing and July 2020 in Dalian, community screening identified 26% and 22% of infections, respectively.[25] In order to test large populations quickly, China commonly used pooled testing, combining five to ten samples before testing, and retesting all individuals in each batch that tested positive.[25]

Zero-COVID implementation by region

[edit]Australia

[edit]

The first confirmed case in Australia was identified on 25 January 2020, in Victoria, when a man who had returned from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, tested positive for the virus.[31] A human biosecurity emergency was declared on 18 March 2020. Australian borders were closed to all non-residents on 20 March,[32] and returning residents were required to spend two weeks in supervised quarantine hotels from 27 March.[33] Many individual states and territories also closed their borders to varying degrees, with some remaining closed until late 2020,[34] and continuing to periodically close during localised outbreaks.[35]

Social distancing rules were introduced on 21 March, and state governments started to close "non-essential" services.[36][37] "Non-essential services" included social gathering venues such as pubs and clubs but unlike many other countries did not include most business operations such as construction, manufacturing and many retail categories.[38]

During the second wave of May and June 2020, Victoria underwent a second strict lockdown with the use of helicopters and the Army to help the police enforce the Zero-COVID lockdown, which would become a norm of deployment, such as during the COVID-19 Delta variant outbreak in Sydney a year later.[39][40] The wave ended with zero new cases being recorded on 26 October 2020.[41][42][43] Distinctive aspects of that response included early interventions to reduce reflected transmission from countries other than China during late January and February 2020; early recruitment of a large contact tracing workforce;[44] comparatively high public trust in government responses to the pandemic, at least compared to the United States;[45] and later on, the use of short, intense lockdowns to facilitate exhaustive contact tracing of new outbreaks.[46][47] Australia's international borders also remained largely closed, with limited numbers of strictly controlled arrivals, for the duration of the pandemic.[48] Australia sought to develop a Bluetooth-based contact tracing app that does not use the privacy-preserving Exposure Notification framework supported natively by Android and Apple smartphones, and while these efforts were not particularly effective,[49][50][51] QR code–based contact tracing apps became ubiquitous in Australia's businesses.[52][53][54]

In July 2021, the Australian National Cabinet unveiled plans to live with COVID and end lockdowns and restrictions contingent on high vaccine uptake.[55] By August 2021, amid outbreaks in New South Wales, Victoria, and the ACT, Prime Minister Scott Morrison conceded a return to Zero-COVID was highly unlikely.[56] Over the following months, each Australian jurisdiction began a living with COVID strategy either through ending lockdowns or voluntarily allowing the virus to enter by opening borders.[57][58]

Bhutan

[edit]As of January 2022, Bhutan was following a Zero-COVID strategy. The country enforced lockdowns on districts (dzongkhags) whenever local cases of COVID-19 were detected, and health personnel isolated elderly people and others with comorbidities who were in close contact with those COVID-19 cases.[5] However, the Omicron variant challenged Bhutan's elimination strategy, and the country abandoned it in mid-April, instead focusing on hospitalization rates.[6]

Canada (Atlantic and Northern)

[edit]

The virus was confirmed to have reached Canada on 27 January 2020, after an individual who had returned to Toronto from Wuhan, Hubei, China, tested positive. The first case of community transmission in Canada was confirmed in British Columbia on 5 March.[59] In March 2020, as cases of community transmission were confirmed, all of Canada's provinces and territories declared states of emergency. Provinces and territories have, to varying degrees, implemented prohibitions on gatherings, closures of non-essential businesses and restrictions on entry with Atlantic Canada and the three Canadian Territories adopting a COVID-Zero approach.[60] On 24 June 2020, it was announced that the four Atlantic provinces: New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador had come to an agreement of creating a free-travel bubble while maintaining low case numbers inside, effective 3 July 2020.[61][62] In late November 2020, mounting cases led to the disbandment of the Atlantic Bubble,[63] with each of the Atlantic provinces maintaining their own travel restrictions and Zero-COVID policies after the bubble burst.[64] Throughout 2020 and 2021, infection rates and deaths in the Atlantic provinces remained low, especially compared to the more populated areas of Canada which did not implement COVID-Zero.[60] The appearance of the Delta and Omicron variants led to the successive abandonment of COVID-Zero in Atlantic Canada at the end of 2021.[64]

China

[edit]Mainland

[edit]

China was the first country to experience the COVID-19 pandemic. The first cluster of pneumonia patients was discovered in late December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, and a public notice on the outbreak was distributed on 31 December 2019.[66]

On 23 January 2020, the Chinese government banned travel to and from Wuhan, and began implementing strict lockdowns in Wuhan and other cities throughout China.[66] These measures suppressed transmission of the virus below the critical threshold, bringing the basic reproduction number of the virus to near zero.[66] On 4 February 2020, around two weeks after the beginning of the lockdowns in Hubei province, case counts peaked in the province and began to decline thereafter.[66] The outbreak remained largely concentrated within Hubei province, with over 80% of cases nationwide through 22 March 2020 occurring there.[27]

The death toll in China during the initial outbreak was approximately 4,600 according to official figures (equivalent to 3.2 deaths per million population),[67] and has been estimated at under 5,000 by a scientific study of excess pneumonia mortality published in The BMJ.[68]

As the epidemic receded, the focus shifted towards restarting economic activity and preventing a resurgence of the virus.[69] Low- and medium-risk areas of the country began to ease social distancing measures on 17 February 2020.[69] Reopening was accompanied by an increase in testing and the development of electronic "health codes" (using smartphone applications) to facilitate contact tracing.[69] Health code applications contain personalized risk information, based on recent contacts and test results.[69] Wuhan, the last major city to reopen, ended its lockdown on 8 April 2020.[70]

China reported its first imported COVID-19 case from an incoming traveler on 30 January 2020.[69] As the number of imported cases rose and the number of domestic cases fell, China began imposing restrictions on entry into the country.[69] Inbound flights were restricted, and all incoming passengers were required to undergo quarantine.[69]

After the containment of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) argued, "The successful containment effort builds confidence in China, based on experience and knowledge gained, that future waves of COVID-19 can be stopped, if not prevented. Case identification and management, coupled with identification and quarantine of close contacts, is a strategy that works."[4] The China CDC rejected a mitigation strategy, and instead explained that "[t]he current strategic goal is to maintain no or minimal indigenous transmission of SARS-CoV-2 until the population is protected through immunisation with safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines, at which time the risk of COVID-19 from any source should be at a minimum. This strategy buys time for urgent development of vaccines and treatments in an environment with little ongoing morbidity and mortality."[4]

Since the end of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, there have been additional, smaller outbreaks caused by imported cases, which have been controlled through short-term, localized intense public health measures.[70] From July through August 2021, China experienced and contained 11 outbreaks of the Delta variant, with a total of 1,390 detected cases (out of a population of 1.4 billion in mainland China).[71] The largest of these outbreaks, in both geographic extent and in the number of people infected, began in Nanjing.[71] The index case of the outbreak, an airport worker, tested positive on 20 July 2021, and the outbreak was traced back to an infected passenger on a flight from Moscow that had arrived on 10 July.[71] The outbreak spread to multiple provinces before it was contained, with a total of 1,162 detected infections.[71] China made use of mass testing to control several outbreaks. For example, nearly the entire population of the city of Guangzhou—approximately 18 million residents—were tested over the course of three days in June 2021, during a Delta variant outbreak.[72]

In 2022, China faced unprecedented waves of infections caused by the Omicron variant and subvariants, with daily cases reaching record highs in the thousands—levels not seen at any prior point in the pandemic.[73] Similar zero-COVID measures were deployed in some areas with lockdowns in Shenzhen,[74] Shenyang[75] and Jilin.[75] Other areas such as Shanghai had previously adopted a less strict approach avoiding wholesale lockdowns,[76][77] only to issue a snap lockdown in late March due to rapidly rising case counts.[78] Since 1 April, most areas of Shanghai had instituted "area-separated control".[79] This is widely considered to be the largest lockdown event in China since Hubei in early 2020.[80] These measures have seen some rare pushback from residents over the overzealousness of the implementation and the perceived lack of benefit.[81][82][83][84][85]

Nationwide protests broke out in late November 2022 amid growing discontent among residents over the zero-COVID policy after the 2022 Ürümqi fire and the resulting economic costs.[86] According to The Guardian, global health experts generally agreed that zero-COVID was "unsustainable" in the long term.[87] Paul Hunter, professor of the University of East Anglia said that the vaccines approved in China were not as protective as the main Western vaccines, that vaccination and booster rates for the elderly were too low, and that any lifting of restrictions should be incremental to avoid overwhelming hospitals.[88] In response to the protests, the government loosened and overhauled many of its rules, including detention for people who test positive and compulsory PCR tests, on December 7, 2022.[89][90][91] On 12 December, the Chinese government announced it was taking offline one of the main health code apps, which was key in tracking people's travel history to identify whether they had been to high-risk areas.[92][93] Due to this, many sources reported that China's zero-COVID policy had effectively ended.[94][95][96] China's "zero-COVID" policy, which aimed at stopping the spread of the disease, was one of the strictest, longest-lasting COVID-19 policies in the world.

Hong Kong

[edit]

The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Hong Kong on 23 January 2020.[97] On 5 February, after a five-day strike by front-line medical workers, the Hong Kong government closed all but three border control points – Hong Kong International Airport, Shenzhen Bay Control Point, and Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge Control Point remaining open. Hong Kong was relatively unscathed by the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak. Some experts believe the habit of wearing masks in public since the SARS epidemic of 2003 may have helped keep its confirmed infections rates low.[98] In a study published in April 2020 in the Lancet, the authors expressed their belief that border restrictions, quarantine and isolation, social distancing, and behavioural changes likely all played a part in the containment of the disease up to the end of March.[99]

After a much smaller second wave in late March and April 2020,[100] Hong Kong saw a substantial uptick in COVID cases in July.[101] Experts attributed this third wave to imported cases – sea crew, aircrew members, and domestic helpers made up the majority of 3rd wave infections.[101] Measures taken in response included a suspension of school classroom teaching until the end of the year, and an order for restaurants to seat only two persons per table and close at 10:00 p.m. taking effect on 2 December;[102] a further tightening of restrictions saw, among other measures, a 6:00 p.m. closing time of restaurants starting from 10 December, and a mandate for authorities to order partial lockdowns in locations with multiple cases of COVID-19 until all residents were tested.[103] From late January 2021, the government repeatedly locked down residential buildings to conduct mass testings. A free mass vaccination program with the Sinovac vaccine and Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine was launched on 26 February. The government sought to counter the vaccine hesitancy by material incentives, which led to an acceleration of vaccinations in June.[104] From early 2022, to prevent the spread of the Omicron variant, Hong Kong had been placed under tightened alert until the day it became 70% fully inoculated.[105] Nonetheless, earlier focus and messaging about eliminating all cases had weakened the case for getting vaccinated in the first place, with less than one-quarter of people aged 80 or older having received two doses of a vaccine before Omicron surged.[106]

By mid-February 2022, the Omicron variant had caused the largest outbreak to date in the territory; authorities modified their eradication protocols, but continued to pursue containment.[107] By mid-March, the virus spread rapidly in the densely populated city, and researchers at University of Hong Kong estimated that almost half the population was infected at one point since the start of the outbreak, compared to only 1 percent of the population before the surge.[106][108] Daily new cases peaked to over 70,000 by March, a far cry from the single-digit daily case loads from Hong Kong's successful implementation of Zero-COVID. Total deaths increased from around 200 over the two years of the pandemic[109] to exceeding 7,000 in a span of a few weeks, leading Hong Kong's COVID-19 deaths per capita, once far lower than those of Western nations, to become the highest in the world during March.[108] The massive death toll and high infection rates while maintaining strict eradication protocols led to the calls for authorities to review Hong Kong's Zero-COVID strategy, as well as questioning the sustainability of such an approach with the Omicron variant.[110][111]

Macau

[edit]Macau, like mainland China and Hong Kong, has followed a zero-COVID strategy (Portuguese: Meta Dinâmica de Infecção Zero). The city, whose economy is heavily dependent on revenues from its casinos, has closed its borders to all travelers who are not residents of Greater China. Despite its proximity to mainland China, from the beginning of the pandemic through 11 March 2022, Macau confirmed only 82 total infections and not a single death.[112]

From mid-June to mid-July 2022, Macau saw an unprecedented wave of infections driven by the BA.5 Omicron subvariant. Health authorities imposed restrictions on activities, including ordering residents to stay at home and the closure of non-essential businesses, including for the first time since February 2020, all its casinos.[113] After nine consecutive days of no local cases and over 14 rounds of mandatory mass testing, Macau reopened in what the city's government called a "consolidation period".[114]

In December 2022, in line with mainland China's easing of its zero-COVID policy, Macau eased its testing and quarantine policies.[115]

Montserrat

[edit]The British territory and Caribbean island of Montserrat used a Zero-COVID strategy, using testing and quarantine on inbound travelers to prevent localized outbreaks. It had suffered just 175 cases and two deaths as of April 2022.[116] From 31 December 2021, Montserrat suffered its first major outbreak, with 67 locally transmitted infections and one death.[117] On 1 March 2022, the ministry of health declared the outbreak to be over, having gone 31 days without a locally transmitted case.[118] In October 2022, Montserrat ended measures.[119]

New Zealand

[edit]

New Zealand reported its first case of COVID-19 on 28 February 2020.[120] From 19 March, entry into New Zealand was limited to citizens and residents,[121] and the country began quarantining new arrivals in converted hotels on 10 April.[122]

On 21 March, a four-tier alert level system was introduced, and most of the country was placed under lockdown from 25 March.[123] Due to the success of the elimination strategy, restrictions were progressively lifted between 28 April and 8 June, when the country moved to the lowest alert level, and the last restrictions (other than quarantine for travelers) were removed.[124][125][126][127][128]

After the lifting of restrictions, New Zealand went for 102 days without any community transmission.[129] On 11 August 2020, four members of a single family in Auckland tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, prompting a city-wide lockdown, and lesser restrictions throughout New Zealand.[129] Additional cases related to this cluster of infections were identified over the following weeks. On 21 September, after a week without any new cases of community transmission, restrictions were dropped to the lowest level outside of Auckland. Restrictions in Auckland were eased somewhat two days later,[130] and moved to the lowest level on 7 October.[131]

Additional small outbreaks led to temporary restrictions in parts of New Zealand in February, March, and June 2021.[132]

The country moved to a nationwide lockdown on 17 August 2021, after the detection of one new local case outside of quarantine in Auckland.[133] Over the following weeks, Auckland remained under lockdown as cases rose, while most of the rest of the country progressively eased restrictions.[132] On 4 October 2021, the government of New Zealand announced that it was transitioning away from its zero-COVID strategy, arguing that the Delta variant made elimination infeasible.[134]

North Korea

[edit]North Korea also reportedly follows an "elimination strategy".[135]

North Korea was one of the first countries to close borders due to COVID-19.[136][137] Starting from 23 January 2020, North Korea banned foreign tourists, and all flights in and out of the country were halted. The authorities also started placing patients with suspected COVID, including those with slight, flu-like symptoms, in quarantine for two weeks in Sinuiju.[138][139][140] On 30 January, the state news agency of North Korea, the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), declared a "state emergency", and reported the establishment of anti-epidemic headquarters around the country.[141] Though many parts of the border were closed, the bridge between Dandong and Sinuiju remained open and allowed supplies to be delivered.[142] In late February, the North Korean government said that it would keep the border closed until a cure was found.[143]

On 2 February, KCNA reported that all the people who had entered the country after 13 January were placed under "medical supervision".[141] South Korean media outlet Daily NK reported that five suspected COVID-19 patients in Sinuiju, on the Chinese border, had died on 7 February.[144] The same day, The Korea Times reported that a North Korean female living in the capital Pyongyang was infected.[145] Although there was no confirmation by North Korean authorities of the claims, the country implemented further strict measures to combat the spread of the virus.[146][147] Schools were closed starting on 20 February.[148] On 29 February, Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un called for stronger measures to be taken to prevent COVID-19 from spreading within North Korea.[149]

In early February, the North Korean government took severe measures to block the spread of COVID-19. Rodong Sinmun, the Workers' Party of Korea newspaper, reported that the customs officials at the port of Nampo were performing disinfection activities, including placing imported goods in quarantine.[150] All international flights and railway services were suspended in early February, and connections by sea and road were largely closed over the following weeks.[143] In February, wearing face masks was obligatory, and visiting public places such as restaurants was forbidden. Ski resorts and spas were closed, and military parades, marathons, and other public events were cancelled.[143] Schools were closed throughout the country; university students in Pyongyang from elsewhere in the country were confined to their dormitories.[151][148]

Although South Korean media reported the epidemic had spread to North Korea, the WHO said there were no indications of cases there.[152] On 18 February, Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of North Korea's ruling party, quoted a public health official reiterating that there had been "no confirmed case of the new coronavirus so far". The WHO prioritised aid for North Korea, including the shipment of protective equipment and supplies.[153]

Scotland and Northern Ireland

[edit]Scotland, led by its devolved government, pursued an "elimination" COVID-19 strategy starting from April 2020.[167] The Scottish government's approach diverged with that of the central British government in April 2020, after a UK-wide lockdown began being lifted. Scotland pursued a slower approach to lifting the lockdown than other nations of the UK, and expanded a "test and trace" system.[167] Although Northern Ireland also pursued the strategy[11][168] and Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon advocated for the approach to be adopted by the whole of the UK,[168] the central British government pursued a different mitigation strategy that applied to England, with commentators noting that this combined with an open Anglo-Scottish border could undermine Scotland's attempts at elimination.[169][11][170]

Singapore

[edit]

Singapore recorded its first COVID-19 case on 23 January 2020.[171] With that, many Singaporeans had purchased and worn masks when not at home; practiced social distancing and on 7 February 2020, Singapore raised the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level from Yellow to Orange in response to additional local cases of uncertain origin.[172] On 3 April 2020, a stringent set of preventive measures collectively called the "circuit breaker lockdown" was announced.[173] Stay-at-home order and cordon sanitaire were implemented as a preventive measure by the Government of Singapore in response on 7 April 2020. The measures were brought into legal effect by the Minister for Health with the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations 2020, published on 7 April 2020.[174]

The country introduced what was considered one of the world's largest and best-organised epidemic control programmes.[175][176] The "Control Order" implemented various measures such as; mass testing the population for the virus, isolating any infected people as well as introducing contact tracing apps and strictly quarantining those they had close contact with those infected. All non-essential workplaces closed, with essential workplaces remaining open. All schools transitioned to home-based learning. All food establishments were only allowed to offer take-away, drive-thru and delivery of food. Non-essential advertising at shopping centres are not allowed to be shown or advertised and only advertising from essential service offers and safe management measures such as mask wearing and social distancing are allowed.[177]

These measures helped to prevent these lockdowns after the end of the circuit breaker lockdown measures in June 2020 with reopening being staggered in different steps all the way until April 2021.[178][179] The high transmissibility of the Delta and Omicron variants challenged Singapore's Zero-COVID approach, and the country phased it out after vaccinating the majority of its population in October 2021.[180]

South Korea

[edit]

The first case in South Korea was announced on 20 January 2020.[181] On 4 February 2020, in order to help prevent spread of the disease, South Korea began denying entry to foreigners traveling from China.[182][183] Various other measures have been taken: mass testing the population, isolating infected people, and trace and quarantine of those they had contact with.[184][185] The rapid and extensive testing undertaken by South Korea has been judged successful in limiting the spread of the outbreak, without using drastic measures.[184][186][187] There was no general lockdown of businesses in South Korea, with supermarkets and other retailers remaining open. However, schools, universities, cinemas, and gyms were closed soon after the outbreaks, with schools and universities having online classes.[188]

The government is providing citizens with information in Korean, English, Chinese, and Japanese on how to not become infected and how to prevent spreading the disease as part of its "K-Quarantine" measures. This includes information on cough etiquette, when and how to wear a face mask, and the importance of physical distancing and staying at home.[188] The South Korean government has also been sending daily emergency notifications, detailing information on locations with reported infections and other status updates related to the pandemic.[189] Infected South Koreans are required to go into isolation in government shelters. Their phones and credit card data are used to trace their prior movements and find their contacts. People who are determined to have been near the infected individual receive phone alerts with information about their prior movements.[190]

Taiwan

[edit]

Due to its extensive cultural and economic exchanges with mainland China, Taiwan was initially expected to be at high risk of developing a large-scale outbreak of COVID-19.[191][192]

Immediately after mainland China notified the WHO of a pneumonia cluster in Wuhan on 31 December 2019, Taiwanese officials began screening passengers arriving from Wuhan for fever and pneumonia.[192] This screening was subsequently broadened to all passengers with respiratory symptoms who had recently visited Wuhan.[192] Beginning in early February 2020, all passengers arriving from mainland China, Hong Kong or Macau were required to quarantine at home for 14 days after arrival in Taiwan.[30] Mobile phone data was used to monitor compliance with quarantine requirements.[192]

Public places such as schools, restaurants and offices in Taiwan were required to monitor body temperature of visitors and provide hand sanitizer.[193] Mask-wearing was encouraged, and on 24 January, an export ban and price controls were placed on surgical masks and other types of personal protective equipment.[193]

On 20 March 2020, Taiwan initiated 14-day quarantine for all international arrivals, and began converting commercial hotels into quarantine facilities.[194] In early April, Taiwanese public health officials announced social distancing measures, and mandated mask use in public transport.[30]

The first known case of COVID-19 in Taiwan was identified on 21 January 2020.[193] On 31 January, approximately 3,000 passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship went ashore in Taiwan. Five days later, it was recognized that there was an outbreak on the ship.[195] Taiwanese public health authorities used mobile phone data and other contact tracing measures to identify these passengers and their close contacts for testing and quarantine.[195] No cases related to these passengers were identified in Taiwan.[195]

Taiwan maintained near-zero viral prevalence throughout 2020, totaling just 56 known locally transmitted cases (out of a population of 23.6 million) through 31 December 2020.[191]

Taiwan experienced its largest outbreak from April to August 2021, initially caused by violations of COVID-19 quarantine rules by international flight crews.[196][197] On 15 May 2021, Taiwan identified more than 100 daily cases for the first time since the start of the pandemic.[198] The outbreak was brought to an end on 25 August 2021, when Taiwan recorded no new locally transmitted cases for the first time since May 2021.[199]

In April 2022, the government departed from Zero-COVID, launching a revised strategy—billed as the "new Taiwanese model"—that no longer focuses on total suppression, but rather shifts to mitigating the effects of the pandemic. Premier Su Tseng-chang was cited as saying the new model is not the same as "living with COVID-19", as the virus would not be allowed to spread unchecked, but active prevention of the virus's spread would be balanced with allowing people to live normal lives and a stable reopening of the economy.[200] As of early May 2022, the government has maintained the policy amidst a wave of infections that crossed 30,000 new COVID-19 cases for the first time since the pandemic began, and that Health minister Chen Shih-chung said was on track to reach up to 100,000 new infections daily.[201] On 7 May 2022, Taiwan reported 46,377 new cases, overtaking the United States as the highest daily new case region.[202]

Timor-Leste

[edit]Due to its fragile healthcare system, Timor-Leste would have been deeply affected by a widespread COVID-19 outbreak. The Timor-Leste government implemented a strategy to keep the virus out by closing the border with Indonesia, and only allowing entry of citizens by repatriation flights.[203] This strategy was effective initially. During 2020, the country reported 44 infections and zero fatalities, and the country was able to function normally, with no lockdowns and largely maskless crowds celebrating Christmas in 2020.[203] However, new variants caused a spike beginning in March 2021, prompting mask mandates and some restrictions on business operations.[204] Timorese authorities were able to contain this outbreak by November 2021, and on 30 November, the state of emergency ended. Business restrictions, as well as the outdoor mask mandate, were lifted.[205] The indoor mask mandate was lifted on 7 January 2022, and as of March 2022, the country maintained an elimination strategy to keep out all infections.[citation needed]

Tonga

[edit]Tonga has followed a Zero-COVID policy, but more than a year and a half into the pandemic, on 29 October 2021, the first COVID-19 case—a seasonal worker who returned from New Zealand and entered quarantine—was confirmed. The country's COVID-19 policy caused complications with international aid following the Hunga Tonga volcano eruption in 2022.[206] To keep the country virus-free, an Australian aid flight had to return to base after detecting a case midflight, while HMAS Adelaide (L01) made plans to stay at sea after 23 members of her crew tested positive for COVID-19.[207]

Vietnam

[edit]

The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Vietnam on 23 January 2020, when two Chinese people in Ho Chi Minh City tested positive for the virus.[208][209] In response the government issued a diagnostic and management guidelines for COVID-19, providing instructions on contact tracing and 14-day isolation.[16] Health authorities began monitoring body temperatures at border gates and started detection and contact tracing, with orders for the mandatory isolation of infected people and anyone they had come into contact with.[210]

In 2020, Vietnam was cited by global media as having one of the best-organized epidemic control programs in the world,[211][212][213] along the lines of other highlights such as Taiwan and South Korea.[214] This success has been attributed to several factors, including a well-developed public health system, a decisive central government, and a proactive containment strategy based on comprehensive testing, tracing, and quarantining.[15] However, instead of relying on medicine and technology, the Vietnamese state security apparatus has adopted a widespread public surveillance system along with a public well-respected military force.[215][216]

Starting in April 2021, Vietnam experienced its largest outbreak to date, with over 1.2 million infections recorded by November.[217] This led to two of its largest cities (Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi) and around a third of the country's population coming under some form of lockdown by late July.[218] A degree of complacency after successes in previous outbreaks, and infections originating from foreign workers were all considered to have contributed to the outbreak. In response, government-mandated quarantine for foreign arrivals and close contacts to confirmed cases was extended to 21 days, and accompanying safety measures also tightened up.[219]

In September 2021, Vietnam abandoned its zero-COVID strategy, after a three-month lockdown of Ho Chi Minh City caused major economic disruption in the city and failed to contain the outbreak. The country shifted to a phased reopening and more flexible approach while expanding its vaccination programme.[220][221]

Reception

[edit]Support

[edit]Proponents of the zero-COVID strategy argued that successful execution reduced the number of nationwide lockdowns needed,[222] since the main goal was focused on the elimination of the virus. When the virus was eliminated, people would be at ease given that COVID-19 caused a lot of health impacts. As such, healthcare and economic costs were lower under a zero-COVID strategy because the elimination of the virus allowed new outbreaks to be easily monitored and curtailed, and that there was less economic disruption since only certain areas were affected, which could be easily monitored.[223][224] This resulted in a situation that was less costly to society,[225] that it reduced dependence on pharmaceutical interventions such as vaccines,[226] and that it increased quality of life and life expectancy as there would have been fewer citizens contracting COVID-19.[227]

Opposition

[edit]Chinese virologist Guan Yi had criticized the Chinese government's zero-COVID measures, telling Phoenix Hong Kong Channel that, if the government persisted with the policy for a handful of cases, the economy would have suffered. The implementation of the zero-COVID policy in China resulted in multiple business closures, citywide lockdowns, and stay-at-home notices in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This resulted in loss of revenue and production, leading to an economic contraction in the country. Guan had advocated for increased vaccination and research into the efficacy of homegrown vaccines against new variants, as the vaccines would prevent death and reduce the impact of COVID-19, which could enable people to swiftly recover without interruption from COVID-19.[228]

Other opponents of the zero-COVID strategy argued that the strategy caused the economy to suffer,[229] that before vaccinations were common, elimination strategies lowered herd immunity,[230] that zero-COVID is not sustainable,[231] and that newer variants such as the Omicron variant were so transmissible that the zero-COVID strategy was no longer feasible.[232]

In May 2022, World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus commented that the zero-COVID strategy was no longer considered sustainable based on "the behavior of the virus now" and future trends. The comment was suppressed on the Chinese Internet.[233] The Lancet, mostly supportive of a zero-COVID strategy before the appearance of less severe but more transmissible variants, also published a news article detailing the problems in China's implementation.[234]

All countries which pursued zero-COVID, such as Vietnam, Singapore, and Australia, later decided to discontinue it, citing increased vaccination rates and more transmissible variants.[230] Singapore abandoned zero-COVID in August 2021 after the Delta variant started spreading there, Australia and Vietnam reopened their borders in early 2022, and China—the last major country to hold out on zero-COVID—abandoned its policy on December 7, 2022.

See also

[edit]- Baltic Bubble

- Endemic COVID-19

- Eradication of infectious diseases

- List of COVID-19 pandemic legislation

- Protective sequestration

- Use and development of software for COVID-19 pandemic mitigation

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ simplified Chinese: 动态清零; traditional Chinese: 動態清零; pinyin: Dòngtài qīng líng; lit. 'Dynamic Clearing',[2] Portuguese: Meta Dinâmica de Infecção Zero[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Anna Llupià, Rodríguez-Giralt, Anna Fité, Lola Álamo, Laura de la Torre, Ana Redondo, Mar Callau and Caterina Guinovart (2020) "What Is a Zero-COVID Strategy" Archived 3 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Barcelona Institute for Global Health – COVID-19 & response strategy. "The strategy of control and maximum suppression (zero-COVID) has been implemented successfully in a number of countries. The objective of this strategy is to keep transmission of the virus as close to zero as possible and ultimately to eliminate it entirely from particular geographical areas. The strategy aims to increase the capacity to identify and trace chains of transmission and to identify and manage outbreaks, while also integrating economic, psychological, social and healthcare support to guarantee the isolation of cases and contacts. This approach is also known as 'Find, Test, Trace, Isolate and Support' (FTTIS)"

- ^ "上海封城一个月:官方坚持"动态清零"政策不变 如何解除危机" (in Simplified Chinese). BBC News 中文. 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ "Plano de Resposta de Emergência para a Situação Epidémica da COVID-19 em Grande Escala do Governo da Região Administrativa Especial de Macau (2.ª Versão)". Centro de Coordenação de Contingência do Novo Tipo de Coronavírus. 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Li, Zhongjie; Chen, Qiulan; Feng, Luzhao; Rodewald, Lance; Xia, Yinyin; Yu, Hailiang; Zhang, Ruochen; An, Zhijie; Yin, Wenwu; Chen, Wei; Qin, Ying; Peng, Zhibin; Zhang, Ting; Ni, Daxin; Cui, Jinzhao; Wang, Qing; Yang, Xiaokun; Zhang, Muli; Ren, Xiang; Wu, Dan; Sun, Xiaojin; Li, Yuanqiu; Zhou, Lei; Qi, Xiaopeng; Song, Tie; Gao, George F; Feng, Zijian (4 June 2020). "Active case finding with case management: the key to tackling the COVID-19 pandemic". The Lancet. 396 (10243): 63–70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31278-2. PMC 7272157. PMID 32505220.

- ^ a b Phub Dem (22 January 2022). ""Living with virus" not an option for Bhutan: PM". Kuensel Online. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b Nima Wangdi (3 March 2022). "Fate of lockdowns in your hands now: PM". Kuensel Online. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ MacDonald, Michael (1 May 2021). "The COVID-Zero approach: Why Atlantic Canada excels at slowing the spread of COVID-19". CTV News. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Hong Kong is clinging to 'zero covid' and extreme quarantine. Talent is leaving in droves". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Lou, Loretta (26 March 2021). "Casino capitalism in the era of COVID-19: examining Macau's pandemic response". Social Transformations in Chinese Societies. 17 (2): 69–79. doi:10.1108/STICS-09-2020-0025. S2CID 233650925. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam are leaving their zero-Covid policies behind, but they aren't ready to open up, experts warn". 22 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Scotland is aiming to eliminate coronavirus. Why isn't England?". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin, Timothy (21 June 2021). "The Countries Stuck in Coronavirus Purgatory". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Hale, Erin. "After early success, Taiwan struggles to exit 'zero COVID' policy". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Fildes, Nic (18 January 2022). "Tonga volcano relief effort complicated by 'Covid-free' policy". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ a b Authors, Guest; Roser, Max (5 March 2021). "Emerging COVID-19 success story: Vietnam's commitment to containment". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b Le, Van Tan (24 February 2021). "COVID-19 control in Vietnam". Nature Immunology. 22 (261): 261. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-00882-9. PMID 33627879.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith; Che, Chang; Chien, Amy Chang (2022-12-07). "China Eases 'Zero Covid' Restrictions in Victory for Protesters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ a b c Oliu-Barton, Miquel; Pradelski, Bary S R; Aghion, Philippe; Artus, Patrick; Kickbusch, Ilona; Lazarus, Jeffrey V; Sridhar, Devi; Vanderslott, Samantha (28 April 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 elimination, not mitigation, creates best outcomes for health, the economy, and civil liberties". The Lancet. 397 (10291): 2234–2236. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00978-8. PMC 8081398. PMID 33932328.

- ^ Bhopal, Raj S (9 September 2020). "To achieve "zero covid" we need to include the controlled, careful acquisition of population (herd) immunity". BMJ. 370: m3487. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3487. eISSN 1756-1833. hdl:20.500.11820/59628557-672e-47bb-b490-9c9965179a27. PMID 32907816. S2CID 221538577.

- ^ David Livermore (28 March 2021). "'Zero Covid' – an impossible dream". HART – Health Advisory & Recovery Team. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Mégarbane, Bruno; Bourasset, Fanchon; Scherrmann, Jean-Michel (20 September 2021). "Epidemiokinetic Tools to Monitor Lockdown Efficacy and Estimate the Duration Adequate to Control SARS-CoV-2 Spread" (PDF). Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health. 11 (4): 321–325. doi:10.1007/s44197-021-00007-3. ISSN 2210-6006. PMC 8451385. PMID 34734383.

- ^ a b c d e Baker, Michael G; Kvalsvig, Amanda; Verrall, Ayesha J (13 August 2020). "New Zealand's COVID-19 elimination strategy". The Medical Journal of Australia. 213 (5): 198–200.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.50735. PMC 7436486. PMID 32789868.

- ^ a b "Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand" (PDF). Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. 16 March 2020.

- ^ Oliu-Barton, Miquel; Pradelski, Bary S R; Algan, Yann; Baker, Michael G; Binagwaho, Agnes; Dore, Gregory; El-Mohandes, Ayman; Fontanet, Arnaud; Peichl, Andreas; Priesemann, Viola; Wolff, Guntram B; Yamey, Gavin; Lazarus, Jeffrey V (January 2022). "Elimination versus mitigation of SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of effective vaccines". Lancet Global Health. 10 (1): e142 – e147. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00494-0. PMC 8563003. PMID 34739862.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Chen, Qiulan (2 December 2021). "Rapid and sustained containment of covid-19 is achievable and worthwhile: implications for pandemic response". The BMJ. 375: e066169. doi:10.1136/BMJ-2021-066169. PMC 8634366. PMID 34852997.

- ^ a b Steyn, Nicholas; Plank, Michael J; James, Alex; Binny, Rachelle N; Hendy, Shaun C; Lustig, Audrey (April 2021). "Managing the risk of a COVID-19 outbreak from border arrivals". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 18 (177). doi:10.1098/rsif.2021.0063. PMC 8086931. PMID 33878278.

- ^ a b Zanin, Mark; Xiao, Cheng; Liang, Tingting; Ling, Shiman; Zhao, Fengming; Huang, Zhenting; Lin, Fangmei; Lin, Xia; Jiang, Zhanpeng; Wong, Sook-San (August 2020). "The public health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in mainland China: a narrative review". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 12 (8): 4434–4449. doi:10.21037/jtd-20-2363. PMC 7475588. PMID 32944357.

- ^ a b c d e f g Li, Zhongjie; Liu, Fengfeng; Cui, Jinzhao; Peng, Zhibin; Chang, Zhaorui; Lai, Shengjie; Chen, Qiulan; Wang, Liping; Gao, George F.; Feng, Zijian (15 April 2021). "Comprehensive large-scale nucleic acid–testing strategies support China's sustained containment of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 27 (5): 740–742. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01308-7. PMID 33859409. S2CID 233258711.

- ^ "What is the difference between isolation and quarantine?". HHS.gov. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Lai, Chih-Cheng; Yen, Muh-Yong; Lee, Ping-Ing; Hsueh, Po-Ren (March 2021). "How to Keep COVID-19 at Bay: A Taiwanese Perspective". Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health. 11 (1): 1–5. doi:10.2991/jegh.k.201028.001. PMC 7958278. PMID 33605120.

- ^ "First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia". Australian Government Department of Health. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Burke, Kelly (19 March 2020). "Australia closes borders to stop coronavirus". 7 News. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Schneiders, Ben (3 July 2020). "How hotel quarantine let COVID-19 out of the bag in Victoria". The Age. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Candice (1 December 2020). "Updates: A state by state guide to border closures and travel restrictions". Escape.com.au. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Borders across Australia close in the face of the Victorian COVID-19 outbreak. This is where you can travel". ABC News. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Australia's social distancing rules have been enhanced to slow coronavirus – here's how they work". ABC. 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher; Wahlquist, Calla; Remeikis, Amy (22 March 2020). "Australia coronavirus updates live: NSW and Victoria to shut down non-essential services". The Guardian Australia. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Restrictions on non-essential services". business.gov.au. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Covid in Sydney: Military deployed to help enforce lockdown". BBC News. 30 July 2021.

- ^ Mercer, Phil (26 October 2020). "Covid: Melbourne's hard-won success after a marathon lockdown". BBC News. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "How Victoria's coronavirus response became a public health 'bushfire' with a second-wave lockdown". ABC News (Australia). 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Towell, Noel; Mills, Tammy (18 August 2020). "Family of four staying at Rydges seeded 90% of second-wave COVID cases". The Age. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Daniel Andrews–Premier (26 October 2020). "Statement From The Premier". www.premier.vic.gov.au (Press release). Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus Australia: How contact tracing is closing in on COVID-19". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 April 2020.

- ^ Otterman, Sharon (21 June 2020). "N.Y.C. Hired 3,000 Workers for Contact Tracing. It's Off to a Slow Start". The New York Times.

- ^ Cave, Damien (February 2021). "One Coronavirus Case, Total Lockdown: Australia's Lessons for the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021.

- ^ Falconer, Rebecca (18 November 2020). "South Australia to enter strict "circuit breaker" lockdown for 6 days". Axios.

- ^ "Fortress Australia's COVID-19 breaches expose economic shortcomings". Reuters. 2 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "COVIDSafe app detected just 17 contacts after millions spent". www.9news.com.au. 27 October 2020.

- ^ Bogle, Ariel; Borys, Stephanie (21 May 2020). "Google and Apple release technology to help with coronavirus contact tracing". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Grubb, Ben (29 June 2020). "'There's no way we're shifting': Australia rules out Apple-Google coronavirus tracing method". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Victorian Government QR Code Service". Coronavirus Victoria.

- ^ "Electronic check-in guidance and QR codes". NSW Government. 27 May 2021.

- ^ "COVID SAfe Check-In". SA.GOV.AU: COVID-19. 8 June 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "NATIONAL PLAN TO TRANSITION AUSTRALIA'S NATIONAL COVID RESPONSE". www.pmc.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Morrison says it's 'highly unlikely' Australia will return to zero COVID-19 cases". www.9news.com.au. 22 August 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Jose, Renju; Barrett, Jonathan (11 October 2021). "'Freedom Day': Sydney reopens as Australia looks to live with COVID-19". Reuters. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Tears and cheers as first flights from NSW land in Queensland". www.9news.com.au. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Slaughter, Graham (5 March 2020). "Canada confirms first 'community case' of COVID-19: Here's what that means". CTVNews. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b Nikiforuk, Andrew (2 April 2021). "Canada Is One Big Pandemic Response Experiment. It Proves 'Zero COVID' Is Best". The Tyee. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Ross, Shane (24 June 2020). "Atlantic provinces agree to regional COVID-19 pandemic bubble". CBC News PEI. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Atlantic Provinces Form Travel Bubble" (PDF). The Council of Atlantic Premiers. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Grimes, Jolene. "COVID Cases in Atlantic Bubble Remain Low as Cases Grow Across Canada".

- ^ a b MacDonald, Michael (7 January 2022). "Fast spreading Omicron crushes Atlantic Canada's acclaimed COVID-Zero strategy". National Post. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "出入境健康申报指引". 中央广播电视总台国际在线. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d TIAN, HUAIYU; LIU, YONGHONG; LI, YIDAN; WU, CHIEH-HSI; CHEN, BIN; KRAEMER, MORITZ U. G.; LI, BINGYING; CAI, JUN; XU, BO; YANG, QIQI; WANG, BEN; YANG, PENG; CUI, YUJUN; SONG, YIMENG; ZHENG, PAI; WANG, QUANYI; BJORNSTAD, OTTAR N.; YANG, RUIFU; GRENFELL, BRYAN T.; PYBUS, OLIVER G.; DYE, CHRISTOPHER (31 March 2020). "An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China". Science. 368 (6491): 638–642. Bibcode:2020Sci...368..638T. doi:10.1126/science.abb6105. PMC 7164389. PMID 32234804.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Mathieu, Edouard; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Beltekian, Diana; Roser, Max (5 March 2020). ""China: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile"". Our World in Data. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Liu, Jiangmei; Zhang, Lan; Yan, Yaqiong; Zhou, Yuchang; Yin, Peng; Qi, Jinlei; Wang, Lijun (24 February 2021). "Excess mortality in Wuhan city and other parts of China during the three months of the covid-19 outbreak: findings from nationwide mortality registries". The BMJ. 372: n415. doi:10.1136/bmj.n415. PMC 7900645. PMID 33627311.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhou, Lei; Wu, Zunyou; Li, Zhongjie; Zhang, Yanping; McGoogan, Jennifer M; Li, Qun; Dong, Xiaoping; Ren, Ruiqi; Feng, Luzhao; Qi, Xiaopeng; Xi, Jingjing; Cui, Ying; Tan, Wenjie; Shi, Guoqing; Wu, Guizhen; Xu, Wenbo; Wang, Xiaoqi; Ma, Jiaqi; Su, Xuemei; Feng, Zijian; Gao, George F (5 June 2020). "One Hundred Days of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Prevention and Control in China". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 72 (2): 332–339. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa725. PMC 7314211. PMID 33501949.

- ^ a b Lu, Guangyu; Razum, Oliver; Jahn, Albrecht; Zhang, Yuying; Sutton, Brett; Sridhar, Devi; Ariyoshi, Koya; von Seidlein, Lorenz; Müllerc, Olaf (20 January 2021). "COVID-19 in Germany and China: mitigation versus elimination strategy". Global Health Action. 14 (1). doi:10.1080/16549716.2021.1875601. PMC 7833051. PMID 33472568. S2CID 231663818.

- ^ a b c d Zhou, Lei; Nie, Kai; Zhao, Hongting; Zhao, Xiang; Ye, Bixiong; Wang, Ji; Chen, Cao; Wang, Hong; Di, Jiangli; Li, Jinsong (8 October 2021). "Eleven COVID-19 Outbreaks with Local Transmissions Caused by the Imported SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC — China, July–August, 2021". China CDC Weekly. 3 (41): 863–868. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.213. PMC 8521157. PMID 34703643.

- ^ Rui, Guo (7 June 2021). "Coronavirus: 18 million tests in three days as Guangzhou tries to stem spread in latest outbreak". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ "China reports 1,335 new COVID cases for March 25 vs 1,366 a day earlier". Reuters. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Some areas of China's Shenzhen city to restart work, public transport on March 18". Reuters. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ a b "China locks down city of 9 million and reports 4,000 cases as Omicron tests zero-Covid strategy". the Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 22 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Shanghai rules out citywide Covid-19 lockdown to protect economy". South China Morning Post. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Shanghai, Agence France-Presse in (26 March 2022). "Shanghai rules out full lockdown despite sharp rise in Covid cases". the Guardian. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Shanghai Covid: China announces largest city-wide lockdown". BBC News. 27 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Nina Xiang (17 April 2022). "Xi Jinping's zero-COVID policy puts reign at risk". The Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "Shanghai Covid: China announces largest city-wide lockdown". BBC News. 27 March 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Chinese student protest forces university to ease Covid-19 lockdown". South China Morning Post. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ Analysis by Simone McCarthy (25 March 2022). "Analysis: China doesn't have a Covid exit plan. Two years in, people are fed up and angry". CNN. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Frustration with Covid response grows in China as daily cases near 5,000". the Guardian. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Frustration, fears of citywide lockdown as Omicron tests Shanghai". South China Morning Post. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "China's state media tries to rally support for zero-Covid as discontent grows". South China Morning Post. 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Protests erupt across China in unprecedented challenge to Xi Jinping's zero-Covid policy". CNN. 26 November 2022.

- ^ "China Covid protests explained: why are people demonstrating and what will happen next?". the Guardian. 28 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "As Officials Ease Covid Restrictions, China Faces New Pandemic Risks". the New York Times. 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith; Che, Chang; Chien, Amy Chang (December 7, 2022). "China Eases 'Zero Covid' Restrictions in Victory for Protesters". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "China rolls back some of its most controversial COVID restrictions". NPR.org.

- ^ Cheng, Simone McCarthy, Cheng (2022-12-08). "'The world changed overnight': Zero-Covid overhaul brings joy — and fears — in China". CNN. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "China scraps tracking app as zero-Covid policy is dismantled". the Guardian. 2022-12-12. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ^ Chang, Simone McCarthy, Selina Wang, Wayne (2022-12-12). "China scraps virus tracking app as country braces for Covid impact". CNN. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Economists hail end to zero Covid in China but huge human toll is feared". the Guardian. 2022-12-11. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ "Xi Jinping tied himself to zero-Covid. Now he keeps silent as it falls apart". CNN. 2022-12-16. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ "China's Covid Zero Exit Sees Analysts Rush to Adjust Forecasts". Bloomberg.com. 2022-12-16. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ Cheung, Elizabeth (22 January 2020). "China coronavirus: death toll almost doubles in one day as Hong Kong reports its first two cases". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ "To mask or not to mask: WHO makes U-turn while US, Singapore abandon pandemic advice and tell citizens to start wearing masks". South China Morning Post. 4 April 2020. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Cowling, Benjamin; Ali, Sheikh Taslim; Ng, Tiffany; Tsang, Tim; Li, Julian; Fong, Min Whui; et al. (17 April 2020). "Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study". The Lancet. 5 (5): e279 – e288. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. PMC 7164922. PMID 32311320.

- ^ "How Hong Kong squashed its second coronavirus wave". Fortune. 21 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ a b Ting, Victor; Cheung, Elizabeth (21 July 2020). "How did Hong Kong's third wave of Covid-19 infections start?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Kwan, Rhoda (30 November 2020). "Hong Kong tightens Covid-19 rules – group gatherings limited to 2, eateries to close 10pm, new hotline for rule-breakers". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Chau, Candice (8 December 2020). "Hong Kong plans partial lockdowns for Covid-19 hotspots and more tests, as number of new infections surges". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Soo, Zen (17 June 2021). "Get a jab, win a condo: Hong Kong tries vaccine incentives". AP News. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Zaharia, Marius; Kwok, Donny (31 December 2021). "Hong Kong says Omicron has breached its strict COVID-19 restrictions". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ a b Mueller, Benjamin (21 March 2022). "High Death Rate in Hong Kong Shows Importance of Vaccinating the Elderly". The New York Times.

- ^ Master, Farah (21 February 2022). "Analysis: Hong Kong's 'zero-COVID' success now worsens strains of Omicron spike". Reuters. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ a b "How Hong Kong went from 'zero-Covid' to the world's highest death rate". NBC News. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "How Hong Kong went from Zero Covid success story to the world's worst Omicron wave". inews.co.uk. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Riordan, Primrose (25 February 2022). "EU warns of Hong Kong exodus as diplomats oppose Covid controls". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "'Frank words', warnings prompted Hong Kong leader's rethink of anti-Covid measures". South China Morning Post. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Devin (11 March 2022), "Macau Vaccination Rate Hits 80 Percent, But Zero COVID-19 Policy Remains", Casino.org, retrieved 2 April 2022

- ^ "Macao streets empty after casinos shut to fight outbreak". Associated Press. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "China's gambling hub Macao to ease Covid-19 restrictions". CNN. August 2022.

- ^ "Macau eases Covid-19 rules, allows home quarantine for arrivals, including those from Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Montserrat COVID – Coronavirus Statistics – Worldometer".

- ^ "MONTSERRAT RECORDS SECOND COVID-19 RELATED DEATH". Government of Montserrat. 8 February 2022.

- ^ "COVID-19 Outbreak Over — Ministry of Health Remains Vigilant". Government of Montserrat. 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Testing on Arrival Discontinued". 2 October 2022.

- ^ Cooke, Henry; Chumko, Andre. "Coronavirus: First case of virus in New Zealand". Stuff. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Walls, Jason. "Coronavirus: NZ shutting borders to everyone except citizens, residents – PM Jacinda Ardern". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Jefferies, Sarah; French, Nigel; Gilkison, Charlotte; Graham, Giles; Hope, Virginia; Marshall, Jonathan; McElnay, Caroline; McNeill, Andrea; Muellner, Petra; Paine, Shevaun; Prasad, Namrata; Scott, Julia; Sherwood, Jillian; Yang, Liang; Priest, Patricia (13 October 2020). "COVID-19 in New Zealand and the impact of the national response: a descriptive epidemiological study". The Lancet Public Health. 5 (11): E612 – E623. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30225-5. PMC 7553903. PMID 33065023.

- ^ Cheng, Derek (20 March 2020). "Coronavirus: PM Jacinda Ardern outlines NZ's new alert system, over-70s should stay at home". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Beattie, Alex; Priestley, Rebecca (20 September 2021). "Fighting COVID-19 with the team of 5 million: Aotearoa New Zealand government communication during the 2020 lockdown". Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 4 (1): 100209. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100209. PMC 8460577. PMID 34585139.

- ^ Sachdeva, Sam (20 April 2020). "Ardern: NZ to leave lockdown in a week". Newsroom. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Cooke, Henry (11 May 2020). "Coronavirus: New Zealand will start to move to level 2 on Thursday". Stuff. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Cheng, Derek (25 May 2020). "Live: Mass gatherings to increase to 100 max from noon Friday". Newstalk ZB. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern reveals move to level 1 from midnight". Radio New Zealand. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Graham-McLay, Charlotte (11 August 2020). "New Zealand records first new local Covid-19 cases in 102 days". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Graham-McLay, Charlotte (21 September 2020). "Relief as much of New Zealand eases out of coronavirus restrictions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Albeck-Ripka, Livia (7 October 2020). "New Zealand Stamps Out the Virus. For a Second Time". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ a b "History of the COVID-19 Alert System". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Covid-19 community case: Nationwide level 4 lockdown". Radio New Zealand. 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Frost, Natasha (4 October 2021). "Battling Delta, New Zealand Abandons Its Zero-Covid Ambitions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Kim Jong Un may have pulled off an astounding COVID-19 feat. But there's a looming threat to his power". ABC News. 27 November 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Im, Esther S.; Abrahamian, Andray (20 February 2020). "Pandemics and Preparation the North Korean Way". 38 North. The Henry L. Stimson Center. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Shinkman, Paul D. "North Korea Opens Borders to Aid Amid Coronavirus Threat". Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ hermesauto (21 January 2020). "North Korea to temporarily ban tourists over Wuhan virus fears, says tour company". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "N. Korea quarantines suspected coronavirus cases in Sinuiju". Daily NK. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "North Korea Bars Foreign Tourists Amid Virus Threat, Groups Say". Bloomberg.com. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Berlinger, Joshua; Seo, Yoonjung (7 February 2020). "All of its neighbors have it, so why hasn't North Korea reported any coronavirus cases?". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Russia Delivers Coronavirus Test Kits to North Korea". 12 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b c O'Carroll, Chad (26 March 2020). "COVID-19 in North Korea: an overview of the current situation". NK News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jang Seul Gi (7 February 2020). "Sources: Five N. Koreans died from coronavirus infections". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus spreads to North Korea, woman infected". The Standard. Hong Kong. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Nation steps up fight against novel CoV". The Pyongyang Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Work to Curb the Inflow of Infectious Disease Pushed ahead with". Rodong Sinmun. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ a b Joo, Jeong Tae (21 February 2020). "N. Korea closes schools throughout the country for one month". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Kim warns of 'serious consequences' if virus spreads to N Korea". al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Newstream" 검사검역을 사소한 빈틈도 없게 (in Korean). 9 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Joo, Jeong Tae (18 March 2020). "Sources: N. Korea extends school closures until April 15". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "World Health Organization says there are 'no indications' of coronavirus cases in North Korea". CNBC. 19 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "World Health Organization says there are 'no indications' of coronavirus cases in North Korea". CNBC. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (25 July 2020). "North Korea Declares Emergency After Suspected Covid-19 Case" Archived 28 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times

- ^ Cha, Sangmi; Smith, Josh (25 July 2020). "North Korea declares emergency in border town over first suspected COVID-19 case". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Swimming defector was not infected, says S Korea". BBC. 27 July 2020. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Farge, Emma; Smith, Josh (5 August 2020). "WHO says North Korea's COVID-19 test results for first suspected case 'inconclusive'" Archived 21 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- ^ Cha, Sangmi (14 August 2020). "North Korea lifts lockdown in border town after suspected COVID-19 case 'inconclusive'" Archived 20 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- ^ Political News Team. "16th Meeting of Political Bureau of 7th Central Committee of WPK Held". rodong.rep.kp. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "로동신문". rodong.rep.kp. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "North Korea orders strict lockdown with first official Covid cases". BBC News. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "North Korea admits to Covid outbreak for first time and declares 'severe national emergency'". The Guardian. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "조선중앙통신 | 기사 | 조선로동당 중앙위원회 정치국 국가방역사업을 최대비상방역체계로 이행하기로 결정". Korean Central News Agency. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b "North Korea reports first-ever COVID-19 outbreak". NK News. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "조선중앙통신 | 기사 | 조선로동당 중앙위원회 제8기 제8차 정치국회의 진행". Korean Central News Agency. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Chung, Chaewon (12 May 2022). "North Korea says 6 people dead, 187,800 in quarantine due to 'fever'". NK News. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b Sridhar, Devi; Chen, Adriel (6 July 2020). "Why Scotland's slow and steady approach to covid-19 is working". BMJ. 370: m2669. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2669. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32631899. S2CID 220347771.

- ^ a b Torjesen, Ingrid (3 August 2020). "Covid-19: Should the UK be aiming for elimination?". The BMJ. 370: m3071. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3071. PMID 32747404. S2CID 220922348.

- ^ Landler, Mark (10 July 2020). "In Tackling Coronavirus, Scotland Asserts Its Separateness From England". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Scotland could eliminate the coronavirus – if it weren't for England". New Scientist. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Singapore confirms first case of Wuhan virus". CNA.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Singapore ups outbreak alert to orange as more cases surface with no known links; more measures in force". The Straits Times. 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Ending circuit breaker: phased approach to resuming activities safely". gov.sg. 28 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations 2020". Singapore Statutes Online. 7 April 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.