Inter Milan

| ||||

| Full name | Football Club Internazionale Milano S.p.A.[1][2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) |

| |||

| Short name | Inter | |||

| Founded | 9 March 1908 (as Football Club Internazionale) | |||

| Ground | Stadio Giuseppe Meazza | |||

| Capacity | 75,817 (limited capacity) 80,018 (maximum) | |||

| Owner |

| |||

| Chairman | Giuseppe Marotta[4] | |||

| Head coach | Simone Inzaghi | |||

| League | Serie A | |||

| 2023–24 | Serie A, 1st of 20 (champions) | |||

| Website | inter.it | |||

|

| ||||

Football Club Internazionale Milano, commonly referred to as Internazionale (pronounced [ˌinternattsjoˈnaːle]) or simply Inter, and colloquially known as Inter Milan in English-speaking countries,[5][6][7] is an Italian professional football club based in Milan, Lombardy. Inter is the only Italian side to have always competed in the top flight of Italian football since its debut in 1909.

Founded in 1908 following a schism within the Milan Foot-Ball and Cricket Club (now AC Milan), Inter won its first championship in 1910. Since its formation, the club has won 36 domestic trophies, including 20 league titles, nine Coppa Italia, and eight Supercoppa Italiana. From 2006 to 2010, the club won five successive league titles, equalling the all-time record at that time.[8] They have won the European Cup/Champions League three times: two back-to-back in 1964 and 1965, and then another in 2010. Their latest win completed an unprecedented Italian seasonal treble, with Inter winning the Coppa Italia and the Scudetto the same year.[9] The club has also won three UEFA Cups, two Intercontinental Cups and one FIFA Club World Cup.

Inter's home games are played at the San Siro stadium, which they share with city rivals AC Milan. The stadium is the largest in Italian football with a capacity of 75,817.[10] They have long-standing rivalries with Milan, with whom they contest the Derby della Madonnina, and Juventus, with whom they contest the Derby d'Italia; their rivalry with the former is one of the most followed derbies in football.[11] As of 2024,[update] Inter has the highest home game attendance in Italy and the fourth-highest attendance in Europe.[12] Since May 2024, the club has been owned by American asset management company Oaktree Capital Management.[13] Inter is one of the most valuable clubs in Italian and world football.[14]

History

Foundation and early years (1908–1960)

|

|

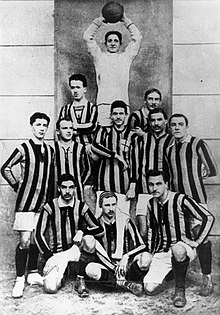

The club was founded on 9 March 1908 as Football Club Internazionale, when a group of players left the Milan Cricket and Football Club (now AC Milan) to form a new club because they wanted to accept more foreign players.[17] The name of the club derives from the wish of its founding members to accept foreign players as well as Italians.[18] The club won its first championship in 1910 and its second in 1920.[19] The captain and coach of the first championship winning team was Virgilio Fossati,[20] who was later killed in battle while serving in the Italian army during World War I.[21]

In 1922, Inter was at risk of relegation to the second division, but they remained in the top league after winning two play-offs.

Six years later, during the Fascist era, the club merged with the Unione Sportiva Milanese and, for political reasons, was renamed Società Sportiva Ambrosiana.[22] During the 1928–29 season, the team wore white jerseys with a red cross emblazoned on it; the jersey's design was inspired by the flag and coat of arms of the city of Milan.[23] In 1929, the new club chairman Oreste Simonotti changed the club's name to Associazione Sportiva Ambrosiana and restored the previous black-and-blue jerseys; however, supporters continued to call the team Inter, and in 1931 new chairman Pozzani succumbed to shareholder pressure and changed the name to Associazione Sportiva Ambrosiana-Inter.

Inter won its third and fourth Serie A title in 1930 and 1938, and also their first Coppa Italia (Italian Cup) was won in 1939, led by Giuseppe Meazza one of the greatest Italian player of all time and the greatest scorer in Inter history with 284 goals, and after whom the San Siro stadium is officially named. A fifth championship followed in 1940, that ended a decade dominated by three teams: Inter, Bologna and the historic rival Juventus.

In the 30's Inter also played for seven times in one of the first major European football cups, the Central European Cup, with Meazza that was a record three times topscorer of the competition; coached by Hungarian Árpád Weisz Inter reached the final of the competition in 1933, when after had won the first leg in Milan 2–1, lost 3–1 in 9 men against Austria Vienna. 4 out of 11 players of that team: Meazza, Luigi Allemandi, Attilio Demaría and Armando Castellazzi would go on to win the 1934 World Cup with Italian national team, while other four Inter players will contribute to the win of 1938 World Cup with Italy: Meazza, Ugo Locatelli, Giovanni Ferrari and Pietro Ferraris.

After the end of World War II, the club's name changed back to its original one, Internazionale,[2] and it come close to win Serie A title in two occasions, one in the last season of Grande Torino in 1949 and in 1951 with the contribution of great players acquired by president Carlo Masseroni in these years, like the first Dutch player in club history Faas Wilkes; Inter will win its sixth championship in 1953 and its seventh in 1954, for the first time in two consecutive years, coached by Alfredo Foni and led by two of the most prolific strikers in club history: István Nyers and Benito Lorenzi with Lennart Skoglund that completed the offensive trio.

In May 1955 Angelo Moratti became the new owner of Inter and despite a disappointment start in the first years with different coaches and players, he put foundations to one of the greatest team in football history.

Grande Inter (1960–1967)

In 1960, manager Helenio Herrera joined Inter from Barcelona, bringing with him Spanish midfielder Luis Suárez in 1961, who won the European Footballer of the Year in the same year for his role in Barcelona's La Liga/Fairs Cup double.[24] He would transform Inter into one of the leading teams in Europe that would win three Serie A titles in four years, two European Cup and two Intercontinental Cup in a row.[25] He modified a 5–3–2 tactic known as the "Verrou" ("door bolt"), which created greater flexibility for counterattacks.[26] The catenaccio system was invented by an Austrian coach, Karl Rappan.[27] Rappan's original system was implemented with four fixed defenders, playing a strict man-to-man marking system, plus a playmaker in the middle of the field, who plays the ball together with two midfield wings. Herrera would modify it by adding a fifth defender, the sweeper or libero, behind the two centre backs. The sweeper or libero, who acted as the free man, would deal with any attackers who went through the two centre backs.[28] Inter finished third in the Serie A in his first season, second the next year and first in his third season. Then followed a back-to-back European Cup victory in 1964 and 1965, earning him the title "il Mago" ("the Wizard").[28] The core of Herrera's team were the attacking full-backs Tarcisio Burgnich and Giacinto Facchetti, Armando Picchi the sweeper, Suárez the playmaker, Jair the winger, Mario Corso the left midfielder and Sandro Mazzola, who played on the inside-right.[29][30][31][32][33]

After the Serie A title won in previous season, in 1964 Inter reached the European Cup Final by beating Borussia Dortmund in the semi-final and Partizan in the quarter-final.[34] In the final in Praterstadion, Vienna they met Real Madrid, a team that had reached seven out of the nine finals to date.[34] Mazzola scored two goals and one from Milani in a 3–1 victory, becoming also the first ever team to win the tournament without losing a single game. The team also won the Intercontinental Cup after have lost the first match in Argentine against Independiente 1–0, Inter won second leg 2–0 in San Siro with goals from Mazzola and Corso, in the third decisive match played in Santiago Bernabeu Inter won in extra-time with a goal from Mario Corso, the first Italian club to win the trophy.

In 1964 Inter added other important players Angelo Domenghini, Gianfranco Bedin and another Spanish Joaquín Peiró that played with constance and was decisive in European Cup where three foreign players could play in the same time while in Serie A only two were allowed to play.

A year later, after have defeated Liverpool F.C. in the semi-final second leg 3-0 recovering from a 3–1 defeat at Anfield with Facchetti scoring the decisive goal, Inter repeated the feat by beating two-time winner Benfica in the final held at home, from a Jair goal, and then again beat Independiente in the Intercontinental Cup with a 3–0 win in San Siro, with two goals from Mazzola and one from Peirò, and a draw in Argentine, becoming the first European team to win two times in a row the competition. Inter came close to winning the Treble for the first time in European football history that year, after having also won the Serie A title, but lost the Coppa Italia final against Juventus in a game played in the last days of August 1965.

Inter again reached semifinals of the European cup in 1966, but this time lost against a Real Madrid team that would go on to win the tournament, while in national championship Herrera's squad won the tenth scudetto in club history, the first Star.

At the end of the season Moratti signed two of the greatest players of all time: Franz Beckenbauer[35] and Eusebio,[36] but after 1966 World Cup when Italian National Team was eliminated by North Korea, Italian Federation decided to block new signings of foreign players who will last until 1980, avoided the contract with the two players.

In 1967, after Inter eliminated Real Madrid in quarterfinals, with Suárez injured, Inter lost the European Cup Final in Lisbon 2–1 to Celtic; a week later, despite the first position, with a lost against Mantova in the last match of the championship Inter lost also the Serie A title and a week later the Coppa Italia semifinal against Padova, putting an end de facto to the Grande Inter cicle with the first season without trophy since 1961–1962.[37] During that year, the club changed its name to Football Club Internazionale Milano, and in 1968 after 13 years Angelo Moratti sold the team to Ivanoe Fraizzoli, and also Helenio Herrera left the team.

Subsequent achievements (1967–1991)

Following the golden era of the 1960s, Inter managed to win their eleventh league title in 1971 with Roberto Boninsegna that leaded the league with 24 goals, and their twelfth in 1980.[38] Inter were defeated for the second time in five years in the final of the European Cup, losing 0–2 to Johan Cruyff's Ajax in 1972. During the 1970s and the 1980s, Inter also added two to its Coppa Italia tally, in 1977–78 and 1981–82 under coach Eugenio Bersellini.

Italian federation reopened the possibility to sign foreign players in 1980, Inter signed among others Hansi Müller (1975–1982 VfB Stuttgart, 1982–1984 Inter), Karl-Heinz Rummenigge (1974–1984 Bayern Munich, 1984–1987 Inter) and Argentinian Daniel Passarella (1986–1988 Inter); other important players in that time were Italians Graziano Bini, Walter Zenga, Giuseppe Bergomi, Alessandro Altobelli, Gabriele Oriali, Riccardo Ferri, Gianpiero Marini and Giuseppe Baresi: Bergomi, Oriali, Marini and Altobelli were part of Italy squad that won 1982 FIFA World Cup.

In 1981 Inter reached for the sixth time in six participations European Cup Semifinals this time against Real Madrid, a classic match that will repeat in 3 different European competitions in the 80's: in UEFA Cup Winners' Cup quarter-finals in 1983 and in Uefa Cup semi-finals in 1985 and 1986.

Led by the German duo of Andreas Brehme and Lothar Matthäus, with Aldo Serena top scorer in Serie A with 22 goals, Argentine Ramón Díaz and Nicola Berti, Inter coached by Giovanni Trapattoni captured the 1989 Serie A championship ended with an all-time record for most points in Serie A history with 18 teams, with 58 points out of 68. Inter were unable to defend their title in the following season in a very competitive Serie A, despite adding fellow German Jürgen Klinsmann to the squad and winning their first Supercoppa Italiana at the start of the season.

Mixed fortunes (1991–2004)

The 1990s was a lackluster period. While their great rivals Milan and Juventus were achieving success both domestically and in Europe, Inter enjoyed little success in the domestic league standings, their worst coming in 1993–94 when they finished just one point out of the relegation zone. Nevertheless, they achieved some European success, with three UEFA Cup victories, in 1991, 1994 and 1998.

After the win of the 1990 World Cup of West Germany led by three Inter players, Matthews was awarded of Ballon d'Or and ended 1990–1991, his most prolific season in career, with 23 goals including 6 in 1991 UEFA Cup won against Roma in May 1991, the first European trophy since the Grande Inter period.

In 1992, after a disappointing season, in sostitution[clarification needed] of the German trio that left in the summer and with the new coach Osvaldo Bagnoli, Inter signed important players like the future Ballon d'Or Matthias Sammer, Rubén Sosa, the first Russian player in club history Igor Shalimov and others that will delude like Darko Pancev and Salvatore Schillaci; Inter ended the season second behind AC Milan coached by Fabio Capello.

In the following season Inter acquired from Ajax Wim Jonk and Dennis Bergkamp that, with 8 goals in the competition, led Inter to their second victory in UEFA Cup despite the worst result in club history in Serie A.

With Massimo Moratti's takeover from Ernesto Pellegrini in 1995, Inter twice broke the world record transfer fee in this period (£19.5 million for Ronaldo from Barcelona in 1997 and £31 million for Christian Vieri from Lazio two years later).[39] Among Moratti first acquisitions in 1995 there were Javier Zanetti from Banfield, that will stay at Inter until 2014 with a record of 858 game played and with a record 13 season as a captain, Paul Ince from Manchester United and Roberto Carlos from Palmeiras that will be sold the next season to Real Madrid with many regrets and recriminations from fans.

However, the 1990s remained the only decade in Inter's history, alongside the 1940s, in which they did not win a single Serie A championship. This persistent lack of success led to poor relations between the fanbase and the chairman, the managers, and even some individual players.

Moratti later became a target of the fans, especially when he sacked the much-loved coach Luigi Simoni after a few games into the 1998–99 season, five days after Inter have defeated Real Madrid 3–1 at San Siro in Champions League group stage with two goals from Roberto Baggio, and having just received the Italian manager of the year award for 1998 the day before being dismissed. That season despite 4 coaches changes Inter reached Champions League quarter Finals when it will be eliminated from Manchester United that would go on to win the trophy that year; Inter failed to qualify for any European competition for the first time in seven years, finishing in eighth place.

In the previous seasons in 1996-1997 Inter reached for third time Uefa Cup final losing this time at penalty in Giuseppe Meazza against Schalke 04 with Roy Hodgson that resigned shortly afterwards, instead in 1997-1998 under Simoni Inter had won his third UEFA Cup defending in Paris final Lazio 3–0 with goals from Ivan Zamorano, Zanetti and Ronaldo, and nearly won Serie A title, with many controversial referee decisions culminated in the decisive match against Juventus in Turin with Inter behind only 1 point with 4 games left, when referee didn't concede a penalty on Ronaldo and after few seconds conceded a penalty for Juventus, that generated a turmoil on the pitch and a big scandal, with president Moratti that left the building shortly afterwards.

The following season, 1999–2000, Moratti appointed former Juventus manager Marcello Lippi, and signed players such as Angelo Peruzzi, Laurent Blanc and Clarence Seedorf from Real Madrid, together with other former Juventus players Vieri and Vladimir Jugović and sold important players like Diego Simeone, Youri Djorkaeff and Gianluca Pagliuca. The team came close to their first domestic success since 1989 when they reached the Coppa Italia final, only to be defeated by Lazio, in a match remembered for the second severe injury to the right knee of Ronaldo, who was returning after five months of inactivity, and which would keep him out for more than a year and a half.

Inter's misfortunes continued the following season, losing the 2000 Supercoppa Italiana match against Lazio 4–3, after initially taking the lead through new signing Robbie Keane. They were also eliminated in the preliminary round of the Champions League by Swedish club Helsingborgs, with Álvaro Recoba missing a crucial late penalty. Lippi was sacked after only a single game of the new season following Inter's first ever Serie A defeat to Reggina. Marco Tardelli, chosen to replace Lippi, failed to improve results, and is remembered by Inter fans as the manager who lost 6–0 in the city derby against Milan.

In 2002 with new coach Hector Cuper, the acquisition of the second most expensive goalkeeper in the world at that time Francesco Toldo and the return after injury of Ronaldo in pair with Vieri, not only did Inter manage to make it to the UEFA Cup semi-finals, but were also only 45 minutes away from capturing the Scudetto when they needed to maintain their one-goal advantage away to Lazio. Inter were 2–1 up after only 24 minutes. Lazio equalised during first half injury time, and then scored two more goals by Simeone and Simone Inzaghi in the second half to secure victory that saw Juventus win the championship, Roma ended second and Inter third. After brilliant performances and have won 2002 World Cup with Brazil, Ronaldo demanded and ottened to be sold to Real Madrid for €45 million, and was replaced by Hernan Crespo from Lazio for €40 million, Seedorf was sold to AC Milan and Fabio Cannavaro was acquired from Parma.

The next season Inter finished as league runners-up with Vieri that was top scorer of Serie A with 24 goals in 23 matches, while Crespo set a new record for UCL Group stage with 8 goals in 6 matches but missed almost the rest of the season for a severe injury in January. In October 2002 in a home game against Lyon Inter was defeated for the first time in its history at home in European Cup/UEFA Champions League after 33 matches in 39 years.[40] Inter reached 2002–03 Champions League semi-finals against AC Milan, that were played also without Vieri out for injury, losing on the away goals rule with two draw in the same stadium in San Siro.

2003–2004 season started well with an historic win for Inter and for Italian football in Champions League in Highbury against Arsenal of Invincibles with a 3–0 and a win against Dinamo Kyiv, but after a draw against Brescia in Serie A in October coach Cuper was sacked and was replaced by Alberto Zaccheroni that will end up eliminated from Champions League in group stage, and despite acquisition in January of strong players like Dejan Stankovic and Adriano, Inter will finish only 4th. Other members of the Inter "family" during this period who suffered were the likes of Vieri and Cannavaro, both of whom had their restaurants in Milan vandalised after the second defeats of the season to the Rossoneri 3–2 in February 2004 in Serie A, but most important was the resignation from presidency by Massimo Moratti in favour of Giacinto Facchetti in January 2004, that lasted until the premature death of Inter legend in September 2006.

Comeback and unprecedented treble (2004–2011)

On 8 July 2004, Inter appointed former Lazio manager Roberto Mancini as its new head coach, with players who will make the history of Inter like Esteban Cambiasso, Julio Cesar, and in 2005 Walter Samuel and Luis Figo.[41] In his first season, the team collected 72 points from 18 wins, 18 draws and only two losses, as well as winning the Coppa Italia against Roma with two goal from Adriano and later the Supercoppa Italiana in Turin against Juventus with a goal from Juan Sebastián Verón.[42][43] On 11 May 2006, Inter won the Coppa Italia title for the second season in a row after defeating Roma with a 4–1 aggregate victory (a 1–1 scoreline in Rome and a 3–1 win at the San Siro).[44]

Inter were awarded the 2005–06 Serie A championship retrospectively, after title-winning Juventus was relegated and points were stripped from Milan due to the Calciopoli scandal.[45] During the following season, Inter with new players like Maicon, Maxwell, Patrick Vieira, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and the return of Crespo from Chelsea, went on a record-breaking run of 17 consecutive victories in Serie A, starting on 25 September 2006, with a 4–1 home victory over Livorno, and ending on 28 February 2007, after a 1–1 draw at home to Udinese.[46] On 22 April 2007, Inter won their second consecutive Scudetto—and first on the field since 1989—when they defeated Siena 2–1 at Stadio Artemio Franchi, ended the season with an all time Serie A record of 97 points and an all-time record margin of 22 points over second place Roma.[47] Italian World Cup-winning defender Marco Materazzi scored both goals.[48]

In this period Inter also reached two times UCL quarter-finals in 2005 and 2006, and UCL round of 16 in 2007: in the last two occasions Inter was eliminated from away goals rules by Villareal and Valencia.

Inter started the 2007–08 season with the goal of winning both Serie A and Champions League in the year of centenary from the foundation of the club. The team started well in the league, topping the table from the first round of matches, and also managed to qualify for the Champions League knockout stage. However, a late collapse, leading to a 2–0 defeat with ten men away to Liverpool on 19 February in the Champions League,[49] brought manager Roberto Mancini's future at Inter,[50] into question while domestic form took a sharp turn of fortune, with the team failing to win in the three following Serie A games. After being eliminated by Liverpool in the Champions League, Mancini announced his intention to leave his job immediately only to change his mind the following day.[51] On the final day of the 2007–08 Serie A season, Inter played Parma away, that had to win to not be relegated in Serie B after 18 years; Roma scored in Catania and was in the first place until Zlatan Ibrahimović, 10 minutes after have been entered on the pitch in the second half, scored two goals sealed their third consecutive championship.[52][53] Mancini, however, was sacked soon after, due to his previous announcement to leave the club.[54]

On 2 June 2008, Inter appointed former Porto and Chelsea boss José Mourinho as new head coach.[55] In his first season, the Nerazzurri won a Suppercoppa Italiana and a fourth consecutive title, though falling in the Champions League in the first knockout round for a third-straight year, losing to eventual finalist Manchester United.[56] In winning the league title, Inter became the first club in since 1949 to win the title for four consecutive seasons, and joined Torino and Juventus as the only clubs to accomplish this feat, as well as being the first club based outside Turin.

In the summer of 2009 Inter put foundation to maybe the greatest single season of its history: after have signed Diego Milito and Thiago Motta from Genoa, Lúcio from Bayern Munich, the club agreed to sell Ibrahimovic to Barcelona in change for Samuel Eto'o plus 49 millions euros. The transfer session ended with the sign of Wesley Sneijder from Real Madrid in the last days of August. Inter won the 2009–10 Champions League, defeating in round of 16 Ancelotti's Chelsea, Cska Moscow and reigning champions Barcelona in the semi-final, before beating Bayern Munich 2–0 in the final in Madrid, with two goals from Diego Milito.[57] Inter also won the 2009–10 Serie A title by two points over Roma, the fifth consecutive, and the 2010 Coppa Italia by defeating the same side 1–0 in the final.[58] This made Inter the first and only Italian team to win the treble.[59] At the end of the season, Mourinho left the club to manage Real Madrid;[60] he was replaced by Rafael Benítez.

On 21 August 2010, Inter defeated Roma 3–1 and won the 2010 Supercoppa Italiana, their fourth trophy of the year.[61] In December 2010, they claimed the FIFA Club World Cup for the first time after a 3–0 win against Mazembe in the final.[62] However, after this win, on 23 December 2010, due to their declining performance in Serie A, the club fired Benítez.[63] He was replaced by Leonardo the following day.[64]

Leonardo started with 30 points from 12 games, with an average of 2.5 points per game, better than his predecessors Benítez and Mourinho.[65] On 6 March 2011, Leonardo set a new Italian Serie A record by collecting 33 points in 13 games; the previous record was 32 points in 13 games, made by Fabio Capello in the 2004–05 season.[66] Leonardo led the club to the quarter-finals of the Champions League, after have defeated again Bayern Munich in Round of 16, before losing to Schalke 04;[67] Inter ended second in Serie A and won the Coppa Italia title.[68] At the end of the season, however, he resigned,[69] and was followed by new managers Gian Piero Gasperini, Claudio Ranieri and Andrea Stramaccioni, all hired during the following season.

Changes in ownership (2011–2019)

On 1 August 2012, the club announced that Moratti was to sell a minority stake of the club to a Chinese consortium led by Kenneth Huang.[70] On the same day, Inter announced an agreement was formed with China Railway Construction Corporation Limited for a new stadium project, however, the deal with the Chinese eventually collapsed.[71] The 2012–13 season was the worst in recent club history, with Inter finishing ninth in Serie A and failing to qualify for any European competitions. Walter Mazzarri was appointed to replace Stramaccioni as the manager for 2013–14 season on 24 May 2013, having ended his tenure at Napoli.[72] He guided the club to fifth in Serie A and to 2014–15 UEFA Europa League qualification.

On 15 October 2013, an Indonesian consortium (International Sports Capital HK Ltd.) led by Erick Thohir, Handy Soetedjo and Rosan Roeslani, signed an agreement to acquire 70% of Inter shares from Internazionale Holding S.r.l.[73][74][75] Immediately after the deal, Moratti's Internazionale Holding S.r.l. still retained 29.5% of the shares of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.[76] After the deal, the shares of Inter was owned by a chain of holding companies, namely International Sports Capital S.p.A. of Italy (for 70% stake), International Sports Capital HK Limited and Asian Sports Ventures HK Limited of Hong Kong. Asian Sports Ventures HK Limited, itself another intermediate holding company, was owned by Nusantara Sports Ventures HK Limited (60% stake, a company owned by Thohir), Alke Sports Investment HK Limited (20% stake) and Aksis Sports Capital HK Limited (20% stake).

Thohir, who also co-owned Major League Soccer (MLS) club D.C. United and Indonesia Super League (ISL) club Persib Bandung, announced on 2 December 2013 that Inter and D.C. United had formed a strategic partnership.[77] During the Thohir era the club began to modify its financial structure from one reliant on continual owner investment to a more self-sustainable business model, although the club still breached UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations in 2015. The club was fined and received a squad reduction in UEFA competitions, with additional penalties suspended during the probation period. During this time, Roberto Mancini returned as the club manager on 14 November 2014, with Inter finishing eighth. Inter finished 2015–2016 season fourth, failing to return to Champions League.

On 6 June 2016, Suning Holdings Group (via a Luxembourg-based subsidiary Great Horizon S.á r.l.) a company owned by Zhang Jindong, co-founder and chairman of Suning Commerce Group, acquired a majority stake of Inter from Thohir's consortium International Sports Capital S.p.A. and from Moratti family's remaining shares in Internazionale Holding S.r.l.[78] According to various filings, the total investment from Suning was €270 million.[79] The deal was approved by an extraordinary general meeting on 28 June 2016, from which Suning Holdings Group had acquired a 68.55% stake in the club.[80]

The first season of new ownership, however, started with poor performance in pre-season friendlies. On 8 August 2016, Inter parted company with head coach Roberto Mancini by mutual consent over disagreements regarding the club's direction,[81] especially with new signings Joao Mario for 44,75 million € (the second most expensive player in club history at that time) and Gabigol for 29,5 million €. He was replaced by Frank de Boer, who was sacked on 1 November 2016 after leading Inter to a 4W–2D–5L record in 11 Serie A games as head coach.[82] The successor, Stefano Pioli, could not prevent the team from getting the worst group result in UEFA competitions in the club's history.[83] Despite an eight-game winning streak, he and the club parted away before season's end, when it became clear they would finish outside the league's top three for the sixth consecutive season.[84] On 9 June 2017, former Roma coach Luciano Spalletti was appointed as Inter manager, signing a two-year contract,[85] and eleven months later Inter secured a UEFA Champions League group stage spot after going six years without Champions League participation, thanks to a 3–2 victory against Lazio in the final game of 2017–18 Serie A.[86][87] Due to this success, in August the club extended the contract with Spalletti to 2021.[88]

On 26 October 2018, Steven Zhang was appointed as new president of the club,[89] and on 13 December 2018 Giuseppe Marotta officially joined Inter Milan as CEO for sport. On 25 January 2019, the club officially announced that LionRock Capital from Hong Kong had reached an agreement with International Sports Capital HK Limited, in order to acquire its 31.05% shares in Inter and to become the club's new minority shareholder.[90] After the 2018–19 Serie A season, despite Inter finishing fourth, Spalletti was sacked.[91]

Renewed successes (2019–present)

On 31 May 2019, Inter appointed former Juventus and Italian manager Antonio Conte as their new coach, signing a three-year deal;[92] In the summer of 2019 Inter acquired from Manchester United for 74 million € Romelu Lukaku, the new most expensive player in the history of the club, Nicolò Barella for 44,5 million € from Cagliari and sold Mauro Icardi, one of the best striker in Italy in the past years, to PSG for 50 million €.

In September 2019, Steven Zhang was elected to the board of the European Club Association.[93] In the 2019–20 Serie A, Inter Milan finished as runner-up, as they won 2–0 against Atalanta on the last matchday.[94] They also reached the 2020 UEFA Europa League final, ultimately losing 3–2 to Sevilla.[95] Inter improved team with signigns of new players, among others in January 2020 Christian Eriksen from Tottenham for 27 million € and in July Achraf Hakimi from Borussia Dortmund for 43 million €.

Despite the worst group result in Champions League in the club's history, following Atalanta's draw against Sassuolo on 2 May 2021, Internazionale were confirmed as champions for the first time in eleven years, ending Juventus's run of nine consecutive titles.[96] However, despite securing Serie A glory, Conte left the club by mutual consent on 26 May 2021. The departure was reportedly due to disagreements between Conte and the board over player transfers.[97][98] In June 2021, Simone Inzaghi was appointed as Conte's replacement.[99] On 6 July 2021 Achraf Hakimi was sold to Paris Saint Germain for €60 million and on 8 August 2021, Romelu Lukaku was sold to Chelsea for €115 million, representing the most expensive association football transfer by an Italian football club ever.[100][101]

Inter qualified in the UCL Round of 16 for the first time in ten years, but despite the club's first ever win at Anfield Road thanks to a goal from Lautaro Martinez, they were eliminated by Liverpool. On 12 January 2022, Inter won the Supercoppa Italiana, defeating Juventus 2–1 at San Siro. After conceding a goal to the opponent, Inter equalised with a penalty scored by Lautaro Martínez, and the match finished 1–1 in regulation time. In the last second of the extra-time, Alexis Sánchez scored the winning goal following a defensive error, giving Inter the first trophy of the season, also Simone Inzaghi's first trophy as Inter manager.[102] On 11 May 2022, Inter won the Coppa Italia, defeating Juventus 4–2 at Stadio Olimpico. After normal time had ended 2–2, with Nicolò Barella and Hakan Çalhanoğlu scoring Inter's goals, Ivan Perišić's brace in the extra-time gave Inter the win and a second title of the season.[103] The 2021–22 Serie A campaign saw Inter finish in second place, being the most prolific attacking side with 84 goals.[104] On 18 January 2023, Inter won the Supercoppa Italiana, defeating Milan 3−0 at King Fahd International Stadium, thanks to goals from Federico Dimarco, Edin Džeko, and Lautaro Martinez.[105]

Inter passed again UCL group stage after have eliminated Barcelona, and then after have defeated Porto and Benfica, qualified for semifinals of the competition. On 16 May 2023, Inter defeated archrivals Milan in the semi-finals of 2022–23 UEFA Champions League with goals from Dzeko and Henrikh Mkhitaryan in the first leg and a goal from Martinez in the second leg, advanced to the Champions League final for the first time since 2010. However, they were defeated at the Atatürk Olympic Stadium 1−0 by Manchester City after a second half goal from midfielder Rodri.[106]

In January 2024 Inter won its eight Supercoppa Italiana and its third consecutive, in a new format with 4 teams, tying the record set by AC Milan in 90's for consecutive win, after have defeated in Riad Lazio 3-0 and then in the final match Napoli 1–0, with a late goal by Lautaro Martinez.

In July 2023 Inter sold for 50 million € goalkeeper Andre Onana to Manchester United, acquired the prior season for free, like Hakan Calhanoglu in 2021, Henrikh Mkhitaryan in 2022 and Marcus Thuram in 2023.

On 22 April 2024, Inter secured their 20th Serie A title and the second Star by defeating Milan 2–1 at the San Siro in a record sixth consecutive Derby della Madonnina win[107] in a dominant season ended with 94 points, 19 over Milan second, the best attack with 89 goals made and the best defense with only 22 goals conceded with +67 difference, the best in Serie A since 1950–1951 season.[108]

On 22 May 2024, Oaktree Capital Management assumed ownership of Inter Milan following the default of Suning Holdings Group on a substantial loan given in May 2021 to the club in order to cover losses incurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.[109] The firm took control of the club after Suning Holdings Group failed to repay a debt of €395 million ($428 million). This development was confirmed by Oaktree in an emailed statement.[110] As a consequence, the new ownership chose to appoint CEO Giuseppe Marotta as the club's new chairman.

Colours and badge

One of the founders of Inter, a painter named Giorgio Muggiani, was responsible for the design of the first Inter logo in 1908.[111] The first design incorporated the letters "FCIM" in the centre of a series of circles that formed the badge of the club.[111] The basic elements of the design have remained constant even as finer details have been modified over the years. Starting from the 1999–2000 season, the original club crest was reduced in size, to create space for the addition of the club's name and foundation year at the upper and lower part of the logo respectively.[2]

In 2007, the logo was returned to the pre-1999–2000 era.[2] It was given a more modern look with a smaller Scudetto star and lighter colour scheme.[2] This version was used until July 2014, when the club decided to undertake a rebranding.[112] The most significant difference between the current and the previous logo is the omission of the star from other media except match kits.[113]

Since its founding in 1908, Inter have almost always worn black and blue stripes, earning them the nickname Nerazzurri. According to the tradition, the colours were adopted to represent the nocturnal sky: in fact, the club was established on the night of 9 March, at 23:30; moreover, blue was chosen by Giorgio Muggiani because he considered it to be the opposite colour to red, worn by the Milan Cricket and Football Club rivals.[114][115]

During the 1928–29 season, however, Inter were forced by Fascist regime to abandon their black and blue uniforms. In 1928, Inter's name and philosophy made the ruling Fascist Party uneasy; as a result, during the same year the 20-year-old club was merged with Unione Sportiva Milanese: the new club was named Società Sportiva Ambrosiana after the patron saint of Milan.[116] The flag of Milan (the red cross on white background) replaced the traditional black and blue.[117] In 1929, the black-and-blue jerseys were restored, and after World War II, when the Fascists had fallen from power, the club reverted to their original name. In 2008, Inter celebrated their centenary with a red cross on their away shirt. The cross is reminiscent of the flag of their city, and they continue to use the pattern on their third kit. In 2014, the club adopted a predominantly black home kit with thin blue pinstripes[118] before returning to a more traditional design the following season.

Animals are often used to represent football clubs in Italy – the grass snake, called Biscione, represents Inter.[119][120] The snake is a symbol for the city of Milan, appearing often in Milanese heraldry as a coiled viper with a man in its jaws. The symbol is present on the coat of arms of the House of Sforza (which ruled over Italy from Milan during the Renaissance period), the city of Milan, the historical Duchy of Milan (a 400-year state of the Holy Roman Empire) and Insubria (a historical region the city of Milan falls within).[119][120] For the 2010–11 season, Inter's away kit featured the snake.

-

1908–1928

-

1963–1979

-

1998–2007

-

2007–2014

-

2014–2021

-

2021–present

Stadium

The team's stadium is the 75,923 seat San Siro,[10] officially known as the Stadio Giuseppe Meazza after the former player who represented for 14 seasons Inter and for two Milan. The more commonly used name, San Siro, is the name of the district where it is located. San Siro has been the home of Milan since 1926, when it was privately built by funding from Milan's chairman at the time, Piero Pirelli. Construction was performed by 120 workers, and took 13+1⁄2 months to complete. The stadium was owned by the club until it was sold to the city in 1935, and since 1947 it has been shared with Inter, when they were accepted as joint tenant.

The first game played at the stadium was on 19 September 1926, when Inter beat Milan 6–3 in a friendly match. Milan played its first league game in San Siro on 19 September 1926, losing 1–2 to Sampierdarenese. From an initial capacity of 35,000 spectators, the stadium has undergone several major renovations. A major structural renovation was made for the 2016 UEFA Champions League Final while another one took place in late 2021 to host the UEFA Nations League final. The stadium is going to be refurbished again in time for Milano Cortina 2026.[121]

Based on the English model for stadiums, San Siro is specifically designed for football matches, as opposed to many multi-purpose stadiums used in Serie A. It is therefore renowned in Italy for its atmosphere during matches, owing to the closeness of the stands to the pitch.

New Milano Stadium

Since 2012, various proposals and projects by Massimo Moratti have alternated regarding a possible construction of a new Inter stadium. [122] Between June and July 2019, Inter and Milan announced the agreement for the construction of a new shared stadium in the San Siro area.[123] In the winter of 2021, Giuseppe Sala, the mayor of Milan, gave official permission for the construction of the new stadium next to San Siro, which is expected to be partially demolished and refunctionalised after the 2026 Olympic Games.[124] In early 2022, Inter and Milan revealed a "plan B" to relocate the construction of the new Milano stadium in the Greater Milan, away from the San Siro area.[125]

Supporters and rivalries

Inter is the second most supported club in Italy, according to an August 2024 research by Ipsos.[126] In the early years (until the First World War), Inter fans from the city of Milan were typically middle class, while Milan fans were typically working class.[115] During Massimo Moratti's ownership, Inter fans were considered to be on the moderate left. At the same time, during Silvio Berlusconi's reign, Milan fans were viewed as belonging to the centre-right.

The traditional ultras group of Inter is Boys San; which are one of the oldest Italian ultras groups, being founded in 1969. Politically, one group (Irriducibili) of Inter Ultras are right-wing and this group has relations with the Lazio ultras. As well as the main group (apolitical) of Boys San, there are five more significant groups: Viking (apolitical), Irriducibili (right-wing), Ultras (apolitical), Brianza Alcoolica (apolitical) and Imbastisci (left-wing).

Inter's most vocal fans gather in the Curva Nord, or north curve of the San Siro. This longstanding tradition has led to the Curva Nord being synonymous with the club's most die-hard supporters, who unfurl banners and wave flags in support of their team. Throughout 2024, the Curva Nord (labelled as the "Curva Nord Milano") have collaborated with rap duo ¥$ (composed of Kanye West and Ty Dolla Sign) on multiple occasions, appearing as a choir on the chart-topping hit song "Carnival" (alongside rapping on its chorus) featuring Playboi Carti and Rich the Kid and on the ¥$ remix of "Like That" featuring only Future and record producer Metro Boomin (Kendrick Lamar would not appear on the remixed version of the song).[127][128]

Inter have several rivalries, two of which are highly significant in Italian football; firstly, they participate in the intracity Derby della Madonnina with Milan; the rivalry has existed ever since Inter splintered off from Milan in 1908.[115] The name of the derby refers to the Blessed Virgin Mary atop the Milan Cathedral. The match usually creates a lively atmosphere, with numerous (often humorous or offensive) banners unfolded before the match. Flares are commonly present, but they also led to the abandonment of the second leg of the 2004–05 Champions League quarter-final matchup between Milan and Inter on 12 April, after a flare thrown from the crowd by an Inter supporter struck Milan keeper Dida on the shoulder.[129]

The other principal rivalry is with Juventus; matches between the two clubs are known as the Derby d'Italia. Up until the 2006 Italian football scandal, which saw Juventus relegated, the two were the only Italian clubs never to have played below Serie A. In the 2000s, Inter developed a rivalry with Roma, who finished as runners-up to Inter in all but one of Inter's five Scudetto-winning seasons between 2005–06 and 2009–10. The two sides have also contested in five Coppa Italia finals and four Supercoppa Italiana finals since 2006. Other clubs, like Atalanta and Napoli, are also considered among their rivals.[130] Their supporters collectively go by Interisti, or Nerazzurri.[131]

Honours

Inter have won 37 domestic trophies, including the Serie A twenty times, the Coppa Italia nine times and the Supercoppa Italiana eight times. From 2006 to 2010, the club won five successive league titles, equalling the all-time record before 2017, when Juventus won their sixth successive league title.[8] They have won the UEFA Champions League three times: two back-to-back in 1964 and 1965 and then another in 2010; the last completed an unprecedented Italian treble with the Coppa Italia and the Scudetto.[9] The club has also won three UEFA Europa League, two Intercontinental Cup and one FIFA Club World Cup.

Inter has never been relegated from the top flight of Italian football in its entire existence. It is the sole club to have competed in Serie A and its predecessors in every season since its debut in 1909.

| Type | Competition | Titles | Seasons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | Serie A | 20 | 1909–10, 1919–20, 1929–30, 1937–38, 1939–40, 1952–53, 1953–54, 1962–63, 1964–65, 1965–66 |

| Coppa Italia | 9 | 1938–39, 1977–78, 1981–82, 2004–05, 2005–06, 2009–10, 2010–11, 2021–22, 2022–23 | |

| Supercoppa Italiana | 8 | 1989, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2021, 2022, 2023 | |

| Continental | European Cup / UEFA Champions League | 3 | 1963–64, 1964–65, 2009–10 |

| UEFA Cup / UEFA Europa League | 3 | 1990–91, 1993–94, 1997–98 | |

| Worldwide | Intercontinental Cup | 2 | 1964, 1965 |

| FIFA Club World Cup | 1 | 2010 |

Club statistics and records

Javier Zanetti holds the records for both total appearances and Serie A appearances for Inter, with 858 official games played in total and 618 in Serie A.

Giuseppe Meazza is Inter's all-time top goalscorer, with 284 goals in 408 games.[132] Behind him, in second place, is Alessandro Altobelli with 209 goals in 466 games, and Roberto Boninsegna in third place, with 171 goals over 281 games.

Helenio Herrera had the longest reign as Inter coach, with nine years (eight consecutive) in charge, and is the most successful coach in Inter history with three Scudetti, two European Cups, and two Intercontinental Cup wins. José Mourinho, who was appointed on 2 June 2008, completed his first season in Italy by winning the Serie A title and the Supercoppa Italiana; in his second season he won the first "treble" in Italian history: the Serie A, Coppa Italia and the UEFA Champions League.

Players

First-team squad

- As of 11 September 2024[133]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Other players under contract

- As of 30 August 2024

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

Out on loan

- As of 11 September 2024

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Youth sector

Inter Primavera players who received a first-team squad call-up.[134] Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Women team

Notable players

Retired numbers

3 – ![]() Giacinto Facchetti, left back, played for Inter 1960–1978 (posthumous honour). The number was retired on 8 September 2006, four days after Facchetti had died from cancer aged 64. The last player to wear the number 3 shirt was Argentinian center back Nicolás Burdisso, who took on the number 16 shirt for the rest of the season.[135]

Giacinto Facchetti, left back, played for Inter 1960–1978 (posthumous honour). The number was retired on 8 September 2006, four days after Facchetti had died from cancer aged 64. The last player to wear the number 3 shirt was Argentinian center back Nicolás Burdisso, who took on the number 16 shirt for the rest of the season.[135]

4 – ![]() Javier Zanetti, defensive midfielder, played 858 games for Inter between 1995 and his retirement in the summer of 2014. In June 2014, club chairman Erick Thohir confirmed that Zanetti's number 4 was to be retired out of respect.[136][137]

Javier Zanetti, defensive midfielder, played 858 games for Inter between 1995 and his retirement in the summer of 2014. In June 2014, club chairman Erick Thohir confirmed that Zanetti's number 4 was to be retired out of respect.[136][137]

Technical staff

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| Head coach | |

| Vice coach | |

| Technical assistant | |

| Fitness coach | |

| Goalkeeper coach | |

| Functional rehab | |

| Head of match analysis | |

| Match analyst | |

| Fitness data analyst | |

| Head of medical staff | |

| Squad doctor | |

| Physiotherapists coordinator | |

| Physiotherapist | |

| Physiotherapist/osteopath | |

| Nutritionist |

Chairmen and managers

Chairmen history

Below is a list of Inter chairmen from 1908 until the present day.[139]

|

|

Managerial history

Below is a list of Inter coaches from 1909 until the present day.[140]

Corporate

FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. was heavily dependent on the financial contribution from the owner Massimo Moratti.[141][142][143][144] In June 2006, the shirt sponsor and the minority shareholder of the club, Pirelli, sold 15.26% shares of the club to Moratti family, for €13.5 million. The tyre manufacturer retained 4.2%.[145] However, due to several capital increases of Inter, such as a reversed merger with an intermediate holding company, Inter Capital S.r.l. in 2006, which held 89% shares of Inter and €70 million capitals at that time, or issues new shares for €70.8 million in June 2007,[146] €99.9 million in December 2007,[147] €86.6 million in 2008,[148] €70 million in 2009,[149][150] €40 million in 2010 and 2011,[151][152][153][154] €35 million in 2012[71][155] or allowing Thoir subscribed €75 million new shares of Inter in 2013, Pirelli became the third largest shareholders of just 0.5%, as of 31 December 2015[update].[156] Inter had yet another recapitalization that was reserved for Suning Holdings Group in 2016. In the prospectus of Pirelli's second IPO in 2017, the company also revealed that the value of the remaining shares of Inter that was owned by Pirelli, was write-off to zero in 2016 financial year. Inter also received direct capital contribution from the shareholders to cover loss which was excluded from issuing shares in the past. (Italian: versamenti a copertura perdite)

Right before the takeover of Thohir, the consolidated balance sheets of "Internazionale Holding S.r.l." showed the whole companies group had a bank debt of €157 million, including the bank debt of a subsidiary "Inter Brand Srl", as well as the club itself, to Istituto per il Credito Sportivo (ICS), for €15.674 million on the balance sheet at the end of the 2012–13 financial year.[157] In 2006, Inter sold its brand to the new subsidiary, "Inter Brand S.r.l.", a special purpose entity with a shares capital of €40 million, for €158 million (the deal made Internazionale make a net loss of just €31 million in a separate financial statement[158][159]). At the same time, the subsidiary secured a €120 million loan from Banca Antonveneta,[160] which would be repaid in installments until 30 June 2016;[161] La Repubblica described the deal as "doping".[162] In September 2011, Inter secured a loan from ICS by factoring the sponsorship of Pirelli of 2012–13 and 2013–14 season, for €24.8 million, in an interest rate of 3 months Euribor + 1.95% spread.[153] In June 2014, new Inter Group secured €230 million loan[163][164][165] from Goldman Sachs and UniCredit at a new interest rate of 3 months Euribor + 5.5% spread, as well as setting up a new subsidiary to be the debt carrier: "Inter Media and Communication S.r.l.". €200 million of which would be utilized in debt refinancing of the group. The €230million loan, €1 million (plus interests) would be due on 30 June 2015, €45 million (plus interests) would be repaid in 15 installments from 30 September 2015 to 31 March 2019, as well as €184 million (plus interests) would be due on 30 June 2019.[76] In ownership side, the Hong Kong-based International Sports Capital HK Limited, had pledged the shares of Italy-based International Sports Capital S.p.A. (the direct holding company of Inter) to CPPIB Credit Investments for €170 million in 2015, at an interest rate of 8% p.a (due March 2018) to 15% p.a. (due March 2020).[166] ISC repaid the notes on 1 July 2016 after they sold part of the shares of Inter to Suning Holdings Group. However, in the late 2016 the shares of ISC S.p.A. was pledged again by ISC HK to private equity funds of OCP Asia for US$80 million.[167] In December 2017, the club also refinanced its debt of €300 million, by issuing corporate bond to the market, via Goldman Sachs as the bookkeeper, for an interest rate of 4.875% p.a.[168][169][170]

Considering revenue alone, Inter surpassed city rivals in Deloitte Football Money League for the first time, in the 2008–2009 season, to rank in ninth place, one place behind Juventus in eighth place, with Milan in tenth place.[171] In the 2009–10 season, Inter remained in ninth place, surpassing Juventus (10th) but Milan re-took the leading role as the seventh.[172] Inter became the eighth in 2010–2011,[173] but was still one place behind Milan. Since 2011, Inter fell to 11th in 2011–12, 15th in 2012–13, 17th in 2013–14, 19th in 2014–15[174] and 2015–16 season.[175] In 2016–17 season, Inter was ranked 15th in the Money League.[176]

In 2010 Football Money League (2008–09 season), the normalized revenue of €196.5 million were divided up between matchday (14%, €28.2 million), broadcasting (59%, €115.7 million, +7%, +€8 million) and commercial (27%, €52.6 million, +43%).[177] Kit sponsors Nike and Pirelli contributed €18.1 million and €9.3 million respectively to commercial revenues, while broadcasting revenues were boosted €1.6 million (6%) by Champions League distribution. Deloitte expressed the idea that issues in Italian football, particularly matchday revenue issues, were holding Inter back compared to other big European clubs, and developing their own stadia would result in Serie A clubs being more competitive on the world stage.[177]

In the 2009–10 season, the revenue of Inter was boosted by the sales of Ibrahimović, the treble and the release clause of coach José Mourinho.[178] According to the normalized figures by Deloitte in their 2011 Football Money League, in the 2009–10 season, the revenue had increased €28.3 million (14%) to €224.8 million. The ratio of matchday, broadcasting and commercial in the adjusted figures was 17%:62%:21%.[172]

For the 2010–11 season, Serie A clubs started negotiating club TV rights collectively rather than individually.[179] This was predicted to result in lower broadcasting revenues for big clubs such as Juventus[179] and Inter,[177] with smaller clubs gaining from the loss. Eventually the result included an extraordinary income of €13 million from RAI.[151] In 2012 Football Money League (2010–11 season), the normalized revenue was €211.4 million. The ratio of matchday, broadcasting and commercial in the adjusted figures was 16%:58%:26%.[173]

However, combining revenue and cost, in the 2006–07 season they had a net loss of €206 million[147][180] (€112 million extraordinary basis, due to the abolition of non-standard accounting practice of the special amortization fund), followed by a net loss of €148 million in the 2007–08 season,[148] a net loss of €154 million in 2008–09 season,[149][150] a net loss of €69 million in the 2009–10 season,[152][178] a net loss of €87 million in the 2010–11 season,[151][154][181] a net loss of €77 million in the 2011–12 season,[153] a net loss of €80 million in the 2012–13 season[71] and a net profit of €33 million in 2013–14 season, due to special income from the establishment of subsidiary Inter Media and Communication.[182] All aforementioned figures were in separate financial statement. Figures from consolidated financial statement were announced since the 2014–15 season, which were net losses of €140.4 million (2014–15),[183][184] €59.6 million[184][185] (2015–16 season, before 2017 restatement)[186] and €24.6 million (2016–17).[186][187]

In 2015, Inter and Roma were the only two Italian clubs that were sanctioned by the UEFA due to their breaking of UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations,[188] which was followed by AC Milan which was once barred from returning to European competition in 2018. As a probation to avoid further sanction, Inter agreed to have a three-year aggregate break-even from 2015 to 2018, with the 2015–16 season being allowed to have a net loss of a maximum of €30 million, followed by break-even in the 2016–17 season and onwards. Inter was also fined €6 million plus an additional €14 million in probation.[188]

Inter also made a financial trick in the transfer market in mid-2015, in which Stevan Jovetić and Miranda were signed by Inter on temporary deals plus an obligation to sign outright in 2017, making their cost less in the loan period.[189] Moreover, despite heavily investing in new signings, namely Geoffrey Kondogbia and Ivan Perišić, signings which potentially increased the cost in amortization, Inter also sold Mateo Kovačić for €29 million, making a windfall profit.[189] In November 2018, documents from Football Leaks further revealed that the loan signings such as Xherdan Shaqiri in January 2015, was in fact had inevitable conditions to trigger the outright purchase.[190]

On 21 April 2017, Inter announced that their net loss (FFP adjusted) of the 2015–16 season was within the allowable limit of €30 million.[191] However, on the same day, UEFA also announced that the reduction of squad size of Inter in European competitions would not be lifted yet, due to partial fulfilment of the targets in the settlement agreement.[192] The same announcement was made by UEFA in June 2018, based on Inter's 2016–17 season financial result.[193]

In February 2020, Inter Milan sued Major League Soccer (MLS) for trademark infringement, claiming that the term "Inter" is synonymous with its club and no one else.[194]

On May 22, 2024, US-based investment firm Oaktree Capital Management said it “assumed ownership” of the club, after previous owner, Suning, a Chinese holding company, missed the deadline on a €395 million debt payment taken out during the COVID pandemic.[195] Oaktree had previously guaranteed Suning's loan in 2021 with Suning's ownership stake in the club as collateral.[196] As a result, Suning's default on the loan resulted in Oaktree's right to take control of the organization.[196]

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (chest) | Shirt sponsor (back) | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–1981 | Puma[197] | None[197] | None | None |

| 1981–1982 | Inno-Hit[197] | |||

| 1982–1986 | Mecsport[197] | Misura[197] | ||

| 1986–1988 | Le Coq Sportif[197] | |||

| 1988–1991 | Uhlsport[197] | |||

| 1991–1992 | Umbro[197] | FitGar[197] | ||

| 1992–1995 | Cesare Fiorucci[197] | |||

| 1995–1998 | Pirelli[197] | |||

| 1998–2015 | Nike[197] | |||

| 2015–2016 | Pirelli[197] (Home) / Driver (Away) | |||

| 2016–2021 | Pirelli[197] | Driver | ||

| 2021–2022 | $INTER Fan Token[198] | Lenovo[199] | DigitalBits[200] | |

| 2022–2023 | DigitalBits (Matchday 1-32) / Paramount+ (Matchday 38 & UEFA Champions League Final) | eBay[201] | ||

| 2023–2024 | Paramount+ | U-Power | ||

| 2024– | Betsson.sport | GATE.io |

See also

- Dynasties in Italian football[broken anchor]

- European Club Association

- List of world champion football clubs

Notes

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A.". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "The history and evolution of the Inter crest". Milan: Inter.it. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ List of shareholders on 30 June 2016, document purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A.

- ^ "Inter shareholders approve new Board of Directors". inter.it. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "Inter Milan arrives in Jakarta to prepare for two friendlies". The Jakarta Post. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Grove, Daryl (22 December 2014). "10 Soccer Things You Might Be Saying Incorrectly". Paste. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Cox, Michael (16 March 2023). "From Sporting Lisbon to Athletic Bilbao — why do we get foreign clubs' names wrong?". The Athletic. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Italy – List of Champions". RSSSF. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Inter join exclusive treble club". UEFA.com. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Struttura". sansirostadium.com (in Italian). San Siro. Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Is this the greatest derby in world sports?". Theroar.com.au. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ "Man Utd 3rd, West Ham 8th, PSG 28th - Top 50 highest average attendances in Europe 2023/24". transfermarkt. 30 May 2024. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Suning Holdings Group acquires majority stake of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A." inter.it. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "The World's Most Valuable Soccer Teams". Forbes. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Qualcosa di speciale? La patch 105". inter.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "#WisdomWednesday: 9 March 1908". Inter.it. Milan: F.C. Internazionale Milano. 8 March 2017. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

It will be born here at l'Orologio restaurant, a gathering place for artists. And it will forever be a very talented team. This wonderful night will give us the colours for our crest: black and blue against a backdrop of gold stars. It will be called Internazionale, because we are brothers of the world.

- ^ Gifford, Clive (27 February 2024). "Inter Milan". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

Inter was formed in 1908 by a breakaway group of players from the Milan Cricket and Football Club (now known as AC Milan) who wanted their club to accept more foreign players

- ^ Wright, Chris (6 June 2023). "'Internazionale'? 'Inter Milan'? Just plain 'Inter'? What should we call Manchester City's Champions League final opponents?". espn.com. ESPN. Archived from the original on 24 September 2023. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

[T]he founding members decided to adopt a name that reflected their open-door policy.

- ^ Brennan, Feargal (30 April 2023). "What is the Scudetto in Italy? Meaning, history, and past winners as Napoli near Serie A championship". sportingnews.com. The Sporting News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Bianchi, Mattia (4 November 2023). "Virgilio Fossati: Dal campo di calcio al campo di battaglia" [Virgilio Fossati: From the football field to the battlefield]. MAMe (in Italian). Milan: MAM-E srls. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Milan's legendary Azzurri leaders". fifa.com. Fifa. 9 September 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Storia". FC Internazionale Milano. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ Galasso 2015, pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Who Single-Handedly Changed the Beautiful Game". Sport Illustrated. 7 August 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Grande Inter – A tribute to the eternal side from Milan". El Arte Del Futbol. 17 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Great Team Tactics: Breaking Down Helenio Herrera's 'La Grande Inter'". Bleacher Report. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Sahu, Amogha (2 August 2011). "World Football: The 5 Greatest Tactical Innovations in Football History". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Helenio Herrera: More than just catenaccio". www.fifa.com. FIFA. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Mazzola: Inter is my second family". FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "La leggenda della Grande Inter" [The legend of the Grande Inter] (in Italian). Inter.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "La Grande Inter: Helenio Herrera (1910–1997) – "Il Mago"" (in Italian). Sempre Inter. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ "Great Team Tactics: Breaking Down Helenio Herrera's 'La Grande Inter'". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Fox, Norman (11 November 1997). "Obituary: Helenio Herrera – Obituaries, News". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ a b Sarugia 2007, pp. 59–71.

- ^ "Beckenbauer: "Nel 1966 avevo firmato per l'Inter, ma poi tutto saltò"". 5 November 2014.

- ^ Mario Gherarducci (5 January 2002). "Il rimpianto di Eusebio: "Ero dell'Inter, maledetta Corea"". Corriere della Sera. p. 39. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014.

- ^ UEFA.com. "The official website for European football". UEFA.com. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Toscani, Oliviero (2008). Inter! 100 anni di emozioni 1908-2008 (in Italian). Milan: Skira. ISBN 978-88-6130-622-6.

- ^ Smyth, Rob (17 September 2016). "Ronaldo at 40: Il Fenomeno's legacy as greatest ever No 9, despite dodgy knees". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "L' Inter scende dal treno". archiviostorico.gazzetta.it. 3 October 2002. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Mancini ends Inter wait". UEFA. 7 July 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "L'Inter vince la Coppa Italia" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. 15 June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Colpo grosso in casa Juve Adriano-Veron, è Supercoppa" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 20 August 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Inter wins Coppa Italia". Eurosport. 11 May 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Inter Milan awarded Serie A title". CNN. 26 July 2006. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Un'altra Inter dei record 18 anni dopo il Trap" (in Italian). La Corriere dello Sport. 22 April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Guido Guida (27 May 2007). "L'Inter chiude da cannibale" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Andersson, Astrid (23 April 2007). "Materazzi secures early title for Inter". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Liverpool 2–0 Inter Milan". BBC Sport. 19 February 2008. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Mancini al termine di Inter-Liverpool". inter.it (in Italian). F.C. Internazionale Milano. 12 March 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Moratti: "Sfogo sbagliato" Mancini: "Non lo rifarei"" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "L'Inter esulta sotto la pioggia Ibra mette la firma sullo scudetto" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 18 May 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Bandini, Nicky (19 May 2008). "Inter's blushes spared as Ibrahimovic earns his redemption". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano statement". FC Internazionale Milano. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ "Nuovo allenatore: Josè Mourinho all'Inter" (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "United topple Inter". Eurosport. 9 March 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Bayern Munich 0–2 Inter Milan". BBC Sport. 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Jose Mourinho's Treble-chasing Inter Milan win Serie A". BBC Sport. 16 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Lawrence, Amy (22 May 2010). "Trebles all round to celebrate rarity becoming routine". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Mourinho unveiled as boss of Real". BBC Sport. 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Benitez begins Inter reign with Supercoppa triumph". ESPN FC. 21 August 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "TP Mazembe 0–3 Internazionale". ESPN Soccernet. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "Inter and Benitez separate by mutual agreement". inter.it. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ "Welcome Leonardo! Inter's new coach". inter.it. 24 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ "Leonardo sorpassa Capello, record per il brasiliano". fcinternews.it (in Italian). 6 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Calcio, Inter; Leonardo: io come Capello? È il mio maestro" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 6 March 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Champions: Schalke-Inter 2-1, nerazzurri eliminati". ilsole24ore.com (in Italian). 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Inter vs Palermo Report". Goal.com. 29 May 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Leonardo: in bocca al lupo dall'Inter". inter.it. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ "Press release: Internazionale Holding S.r.l". FC Internazionale Milano. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ a b c FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2013, PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Comunicato ufficiale di F.C. Internazionale". Inter Official Site. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Inter Milan Sells 70% Stake To Indonesia's Erick Thohir At $480M Valuation". Forbes. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano statement". FC Internazionale Milano. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. signs an agreement to open capital to new investors". FC Internazionale Milano. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ a b FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2014, PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano and D.C. United announce collaborative agreement". FC Internazionale Milano. 2 December 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "Suning Holdings Group acquires majority stake of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A." FC Internazionale Milano. 6 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "China's Suning buying majority stake in Inter Milan for $307 million". Reuters. 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Assemblea degli Azionisti di FC Internazionale Milano" [FC Internazionale Milano Shareholders' Meeting] (Press release). FC Internazionale Milano. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano statement". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano statement". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ Stefano Scacchi (9 December 2016). "Eder per l'inutile successo dell'Inter passa la sorpresa Hapoel Be'er Sheva". la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 44. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "FC Internazionale Milano statement". Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Inter Milan name Luciano Spalletti as their new boss on a two-year contract". BBC Sport. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ PA Sport. "Serie A round-up: Inter Milan beat Lazio to claim final Champions League spot". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Lazio 2–3 Inter Milan". BBC Sport. 20 May 2018. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "LUCIANO SPALLETTI EXTENDS INTER CONTRACT TO 2021!" (Press release). F.C. Internazionale Milano. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Steven Zhang named President of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A." inter.it. 26 October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "LionRock Capital Acquires 31.05% of FC Internazionale Milano S.p.A." (Press release). F.C. Internazionale. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Club statement regarding the position of the First Team Head Coach" (Press release). F.C. Internazionale Milano. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "OFFICIAL: Inter appoint Conte". football-italia.net. 31 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "OFFICIAL - Inter President Zhang Elected To ECA Board". SempreInter.com. 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Atalanta 0–2 Inter: Evergreen Young inspires win to secure runner-up spot". Yahoo Sports. 1 August 2020. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Inter Milan 5–0 Shakhtar Donetsk". BBC Sport. 17 August 2020. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Inter Milan: Italian giants win first Serie A for 11 years". BBC Sport. 2 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ ""Antonio Conte leaves Inter Milan after clinching Serie A title -ESPN"". 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Antonio Conte leaves Inter over plan to sell €80m of players this summer". TheGuardian.com. 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Horncastle, James. ""Simone Inzaghi appointed Inter Milan head coach - The Athletic"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Inter, il Chelsea offre 115 milioni cash per Lukaku. Si chiude appena c'è il sostituto". gazzetta.it/. gazzetta.it/. 7 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Addio di Lukaku: proprietà e dirigenti, sono tutti responsabili". gazzetta.it. gazzetta.it. 7 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Inter-Juventus 2-1, gol e highlights: ai nerazzurri la Supercoppa, decide Sanchez al 121'" (in Italian). 13 January 2022. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "L'Inter vince la Coppa Italia: 4-2 contro la Juve ai supplementari" (in Italian). 11 May 2022. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "CLASSIFICA SERIE A 2021/2022" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "La Supercoppa italiana è dell'Inter: 3 a 0 al Milan, gol di Dimarco, Dzeko e Lautaro" (in Italian). 18 January 2023.

- ^ Smith, Rory (10 June 2023). "Champions League Final: Manchester City Wins First Champions League Title". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Internazionale seal historic 20th Serie A title with derby victory over Milan". The Guardian. 22 April 2024. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "I numeri di uno Scudetto straordinario". Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Investment Firm Oaktree Capital Signs $336 Million Financing Deal With Serie A Champions FC Inter". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Morpurgo, Giulia; Perez, Irene Garcia (22 May 2024). "Inter Milan Seized by Oaktree After Chinese Owner Defaults on Debt". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ a b Galasso 2015, p. 241.

- ^ "Nerazzurri rebranding: new logo, same Inter". Inter.it. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Inter rebranding in detail". Inter.it. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "9 marzo 1908, 43 milanisti fondano l'Inter". ViviMilano.it. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "AC Milan vs. Inter Milan". FootballDerbies.com. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ "Emeroteca Coni". Emeroteca.coni.it. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.