Ezra 4

| Ezra 4 | |

|---|---|

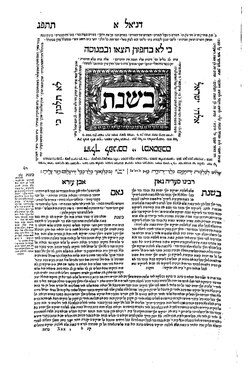

The books of Daniel and Ezra–Nehemiah from the sixth edition of the Mikraot Gedolot (rabbinic bible), published 1618–1619. | |

| Book | Book of Ezra |

| Category | Ketuvim |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 15 |

Ezra 4 is the fourth chapter of the Book of Ezra in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible,[1] or the book of Ezra–Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible, which treats the book of Ezra and book of Nehemiah as one book.[2] Jewish tradition states that Ezra is the author of Ezra–Nehemiah as well as the Book of Chronicles,[3] but modern scholars generally accept that a compiler from the 5th century BCE (the so-called "Chronicler") is the final author of these books.[4] The section comprising chapter 1 to 6 describes the history before the arrival of Ezra in the land of Judah [5][6] in 468 BCE.[7] This chapter records the opposition of the non-Jews to the re-building of the temple and their correspondence with the kings of Persia which brought a stop to the project until the reign of Darius the Great.[8][9]

Text

[edit]This chapter is divided into 24 verses. The original language of 4:1–7 is Hebrew language, whereas of Ezra 4:8–24 is Aramaic.[10]

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew/Aramaic are of the Masoretic Text, which includes Codex Leningradensis (1008).[11][a] Fragments containing parts of this chapter were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, that is, 4Q117 (4QEzra; 50 BCE) with extant verses 2–6 (2–5 // 1 Esdras 5:66–70), 9–11.[13][14][15][16] There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[17][b]

An ancient Greek book called 1 Esdras (Greek: Ἔσδρας Αʹ) containing some parts of 2 Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah is included in most editions of the Septuagint and is placed before the single book of Ezra–Nehemiah (which is titled in Greek: Ἔσδρας Βʹ). 1 Esdras 5:66–73[c] is an equivalent of Ezra 4:1–5 (Work hindered until second year of Darius's reign), whereas 1 Esdras 2:15–26 is an equivalent of Ezra 4:7–24 (Artaxerxes' reign).[21][22]

The oldest Latin manuscript of 4 Esdra is the Codex Sangermanensis that lacks 7:[36]–[105] and is parent of the vast majority of extant manuscripts.[23] Other Latin manuscripts are:

- Codex Ambianensis: a Carolingian minuscule of the ninth century);

- Codex Complutensis: written in a Visighotic hand and dating from the ninth to tenth century, is now MS31 in the Library of Central University at Madrid.

- Codex Mazarineus: in two volumes, dating from the eleventh century, numbered 3 and 4 (formerly 6,7) in the Bibliothèque Mazarine at Paris. The text of 4 Ezra is given in the sequence of chapters 3–16, 1–2.[23]

An offer of help (4:1–5)

[edit]The non-Jewish inhabitants of the land of Judah offered to help with the building, but regarding it as a 'proposal of compromise', the leaders of Judah rejected the offer.[24] Due to the rejection, the surrounding inhabitants mounted opposition to the building project.[25]

Verses 1–2

[edit]- 1 Now when the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin heard that the descendants of the captivity built the temple unto the Lord God of Israel, 2 they came to Zerubbabel, and to the chiefs of the fathers' households, and said to them, "Let us build with you, for, like you, we seek your God and have been sacrificing to Him since the days of Esarhaddon king of Assyria, who brought us here."[26]

- "Adversaries" or "enemies".[27]

- "Zerubbabel": is the leader of the group and of Davidic line (1 Chronicles 3:19), so he is associated with the messianic hope in the book of Zechariah, although none of it is mentioned in this book.[28] His office is not named in this book, but he is identified as the "governor of Judah" in Haggai 1:1, 14; 2:2.[5]

The enemies of the exiles try to destroy that community by assimilation, pointing out important similarities among their peoples (verse 2),[29] wanting the exiles to be entirely like them, but the enemies don't have allegiance to Yahweh and assimilation for the exiles would have meant destruction of the covenant with God.[30] The reference to the Assyrian king recalls the story in 2 Kings 17:1–6 that after the fall of Samaria in 721 BC, the genuine Israel inhabitants of the northern kingdom were deported elsewhere and the Assyrians planted people from other places (bringing their own gods; cf. 2 Kings 17:29) to the region of Samaria, initiated by Sargon (722–705 BC), but from this verse apparently extended to the reign of Esarhaddon (681–669 BC).[29]

Verse 3

[edit]

- But Zerubbabel and Jeshua and the rest of the heads of the fathers' houses of Israel said to them, "You may do nothing with us to build a house for our God; but we alone will build to the Lord God of Israel, as King Cyrus the king of Persia has commanded us."[31]

- "Jeshua": or "Joshua".[32] His office is not named in this book, but he is identified as the "high priest" in Haggai 1:1, 12, 14; 2:2; Zechariah 3:1.[5]

- "House" refers to "Temple".[33]

The rejection of Zerubbabel was based on "spiritual insight".[30]

Verses 4–5

[edit]- 4 Then the people of the land demoralized the people of Judah and terrified them while building, 5 and hired counselors against them to frustrate their purpose, all the days of Cyrus king of Persia, even until the reign of Darius king of Persia.[34]

- "To frustrate their purpose": in sense of 'to seek, "under the guise of advice and interest, to seduce the exiles from following the mind of God to follow a different mind"'.[30]

Historical divergence (4:6–23)

[edit]The story of Zerubbabel was interrupted by the list of some accounts of hostilities which happened in a long period of time to illustrate the continuous opposition by non-Jews of the area to the attempts of the Jews to establish a community under the law of God.[25]

Verse 6

[edit]- And in the reign of Ahasuerus, in the beginning of his reign, they wrote an accusation against the inhabitants of Judah and Jerusalem.[35]

- "Ahasuerus": from Hebrew: אֲחַשְׁוֵר֔וֹשׁ, ’ă-ḥaš-wê-rō-wōš,[36] "Ahashverosh’"; Persian: "Khshyarsha", transliterated in Greek as "Xerxes", generally identified with the well-known Xerxes I, the son of Darius (reigned 20 years: 485–465 BCE), who is also associated with Ahasuerus of the book of Esther.[37] A view regards "Ahasuerus" (and "Artaxerxes" in verse 7) to be an appellative, like Pharaoh and Caesar, so it could be applied to any Persian monarch, and thus identifies "Ahasuerus" with Cambyses, the son of Cyrus (the same Cambyses is called "Artaxerxes" by Josephus in Ant. xi. 2. 1), but no well-attested evidence exists of this argument.[37]

Verse 7

[edit]- In the days of Artaxerxes also, Bishlam, Mithredath, Tabel, and the rest of their companions wrote to Artaxerxes king of Persia; and the letter was written in Aramaic script, and translated into the Aramaic language.[38]

- "Artaxerxes": from Hebrew: ארתחששתא (also written as ארתחששת), ’ar-taḥ-šaś-tā,[39] also mentioned in Ezra 7:1; Nehemiah 2:1, generally identified with Artaxerxes Longimanus, who succeeds his father Xerxes and reigned forty years (465–425 BCE).[37] The name in the inscriptions appears as "Artakshathra", compounded of "Arta" meaning "great" (cf. Arta-phernes, Arta-bazus) and "Khsathra", "kingdom".[37] The view which identifies this Artaxerxes with Pseudo-Smerdis or Gomates, the usurper of the Persian crown on the death of Cambyses, has no well-attested evidence.[37]

- "And the letter was written in Aramaic script, and translated into the Aramaic language": from Hebrew: וכתב הנשתון כתוב ארמית ומתרגם ארמית, ū-ḵə-ṯāḇ ha-niš-tə-wān kā-ṯūḇ ’ă-rā-mîṯ ū-mə-ṯur-gām ’ă-rā-mîṯ,[39] MEV: "the writing of the letter was written in Aramaic, and interpreted in Aramaic", indicating that Ezra 4:8–6:18 is in Aramaic.[40]

Verses 9–10

[edit]- 9 then Rehum the chancellor, Shimshai the scribe, and the rest of their companions, the Dinaites, and the Apharsathchites, the Tarpelites, the Apharsites, the Archevites, the Babylonians, the Shushanchites, the Dehaites, the Elamites, 10 and the rest of the nations whom the great and noble Osnappar brought over, and set in the city of Samaria, and in the rest of the country beyond the River, and so forth, wrote.[41]

- "Osnappar" (referring to "Ashurbanipal" (669–626 BC);[42] Hebrew: אסנפר, ’ā-sə-na-par[43]) is the last of the great Assyrian kings, considered by people in the imperial provinces simply as a predecessor of the Persian king Artaxerxes (despite the changes of the power); the mention of his name is a tactic to scare the king of the projection of less income from the population in that area if they are rebelling against him.[42] Evidently troubled by the thought of losing revenue (verses 20, 22) and with the Assyrian and Babylonians annals available for him, possibly containing records of the "chronically rebellious city" of Jerusalem, Artaxerxes was convinced and ordered the work to be stopped (verse 23).[44]

The story resumed (4:24)

[edit]With the repetition of the essence in verse 5, the story of Zerubbabel and Jeshua resumes, continued in the next chapter.[45]

Verse 24

[edit]- Then ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia.[46]

- "The second year" corresponds to 520 BC.[47]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Since 1947 the current text of Aleppo Codex is missing the whole book of Ezra-Nehemiah.[12]

- ^ The extant Codex Sinaiticus only contains Ezra 9:9–10:44.[18][19][20]

- ^ 1 Esdras doesn't mention the name "Ahasuerus"

References

[edit]- ^ Halley 1965, p. 233.

- ^ Grabbe 2003, p. 313.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Baba Bathra 15a, apud Fensham 1982, p. 2

- ^ Fensham 1982, pp. 2–4.

- ^ a b c Grabbe 2003, p. 314.

- ^ Fensham 1982, p. 4.

- ^ Davies, G. I., "Introduction to the Pentateuch" in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001), The Oxford Bible Commentary Archived 2017-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, p. 19

- ^ Smith-Christopher 2007, p. 313–314.

- ^ Levering 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Note d at Ezra 4:8 in the New King James Version: "The original language of Ezra 4:8 through 6:18 is Aramaic".

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 36–37.

- ^ P. W. Skehan (2003), "BIBLE (TEXTS)", New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 355–362

- ^ Ulrich 2010, p. 776.

- ^ Dead sea scrolls - Ezra

- ^ Fitzmyer 2008, p. 43.

- ^ 4Q117 at the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Würthwein, Ernst (1988). Der Text des Alten Testaments (2nd ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. p. 85. ISBN 3-438-06006-X.

- ^ Swete, Henry Barclay (1902). An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek. Cambridge: Macmillan and Co. pp. 129–130.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Esdras: THE BOOKS OF ESDRAS: III Esdras

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Esdras, Books of: I Esdras

- ^ a b Bruce M. Metzger, The Fourth Book of Ezra (Late First Century A.D.) With The Four Additional Chapters. A New Translation and Introduction, in James H. Charlesworth (1985), The Old Testament Pseudoepigrapha, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc., Volume 2, ISBN 0-385-09630-5 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-385-18813-7 (Vol. 2). Here cited vol. 1 p. 518

- ^ Larson, Dahlen & Anders 2005, p. 44.

- ^ a b Larson, Dahlen & Anders 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Ezra 4:1–2 MEV

- ^ Notes [a] on Ezra 4:1 in NKJV

- ^ McConville 1985, p. 14.

- ^ a b McConville 1985, p. 26.

- ^ a b c McConville 1985, p. 27.

- ^ Ezra 4:3 NKJV

- ^ Notes [a] on Ezra 3:2 in NKJV

- ^ Notes [a] on Ezra 4:3 in NKJV

- ^ Ezra 4:4–5 MEV

- ^ Ezra 4:6 ESV

- ^ Hebrew Text Analysis: Ezra 4:6. Biblehub

- ^ a b c d e Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Ezra 4. Accessed 28 April 2019.

- ^ Ezra 4:7 NKJV

- ^ a b Hebrew Text Analysis: Ezra 4:7. Biblehub

- ^ Note [a] on Ezra 4:7 in MEV

- ^ Ezra 4:9–10 WEB

- ^ a b McConville 1985, p. 28.

- ^ Hebrew Text Analysis: Ezra 4:10. Biblehub

- ^ McConville 1985, p. 29.

- ^ Larson, Dahlen & Anders 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Ezra 4:24 KJV

- ^ Barnes, Albert. Notes on the Bible - Ezra 4. James Murphy (ed). London: Blackie & Son, 1884.

Sources

[edit]- Fensham, F. Charles (1982). The Books of Ezra and Nehemiah. New international commentary on the Old Testament (illustrated ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802825278. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802862419.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2003). "Ezra". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (illustrated ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 313–319. ISBN 978-0802837110. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Larson, Knute; Dahlen, Kathy; Anders, Max E. (2005). Anders, Max E. (ed.). Holman Old Testament Commentary - Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther. Holman Old Testament commentary. Vol. 9 (illustrated ed.). B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0805494693. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Levering, Matthew (2007). Ezra & Nehemiah. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431616. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- McConville, J. G. (1985). Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. The daily study Bible : Old Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664245832. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Smith-Christopher, Daniel L. (2007). "15. Ezra-Nehemiah". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 308–324. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Ulrich, Eugene, ed. (2010). The Biblical Qumran Scrolls: Transcriptions and Textual Variants. Brill.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jewish translations:

- Ezra - Chapter 4 (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Book of Ezra Chapter 4. Bible Gateway