Audioslave (album)

| Audioslave | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | November 18, 2002 | |||

| Recorded | May 2001 – June 2002 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 65:26 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer |

| |||

| Audioslave chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Audioslave | ||||

| ||||

Audioslave is the debut studio album by American rock supergroup Audioslave, released on November 18, 2002, through Epic Records and Interscope Records. In the United States, it has been certified triple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. The album spawned the singles "Cochise", "Like a Stone", "Show Me How to Live", "I Am the Highway", and "What You Are"; "Like a Stone" was nominated for Best Hard Rock Performance at the 46th Grammy Awards.

Background and release

[edit]After Zack de la Rocha left Rage Against the Machine, the remaining members of the band began to look for a new vocalist. Producer and friend Rick Rubin suggested they contact Chris Cornell and played them the Soundgarden song "Slaves & Bulldozers" to showcase his ability. Cornell was in the process of writing material for a second solo album when Tom Morello, Tim Commerford, and Brad Wilk approached him, but he decided to shelve that and pursue the opportunity to work with them.

Speaking about the first time Cornell jammed with the band, Morello said: "He stepped to the microphone and sang the song and I couldn't believe it. It didn't just sound good. It didn't sound great. It sounded transcendent. And ... when there is an irreplaceable chemistry from the first moment, you can't deny it."[7] The new quartet wrote 21 songs during 19 days of rehearsal and started recording their first album in late May 2001.[8][9]

On March 19, 2002, the band announced they would be part of the 7th Ozzfest tour that summer, but three days later Cornell quit the group, and the Ozzfest dates were canceled. He rejoined the band six weeks later, after some management issues were resolved.[10]

Rough versions of thirteen songs from the album were leaked onto various peer-to-peer file sharing networks on May 17, 2002, six months before the official release of the album, under the name "Civilian" (or "The Civilian Project").[11] In an interview with Metal Sludge that July, Morello blamed "some jackass intern at Bad Animal Studios in Seattle" for stealing some demos and putting them on the internet without the band's permission.[12] Later, he said that "It was very frustrating, especially with a band like this, there is a certain amount of expectation. For some people the initial time that they are hearing it was not in the form that you would have them hear it. In some cases they weren't even the same lyrics, guitar solos, performances of any kind."[13]

Cornell was having problems with alcohol while making the album, and in late 2002 there was a rumor that he had checked himself into drug rehabilitation—a rumor that was confirmed when he conducted an interview with Metal Hammer from a clinic payphone.[14] He later said that he went through "a horrible personal crisis" during the making of the first Audioslave album, staying in rehab for two months and separating from his wife.[10] He remained sober until shortly before his passing in 2017.

The album was released on November 18, 2002, in the United Kingdom and a day later in the United States.[15] The band toured through 2003, before taking a break from the road in 2004 to record their second album.

Artwork

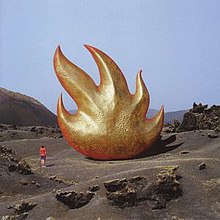

[edit]The cover was designed by Storm Thorgerson (with Peter Curzon and Rupert Truman) – who, as leader of Hipgnosis, was best known for work for Pink Floyd.

"The music of Audioslave struck us as brooding and sultry, carrying a sense of threat as if about to burst asunder or erupt in fury, much like a volcano. We knew therefore the setting against which some thing or some act would either appear or take place… [The flame is] the eternal flame, or the flame of remembrance, embodying the memory of two previous incarnations: namely Soundgarden and Rage Against the Machine. [It is] a large sculpture of metal like a sounding brass, which pilgrims or slaves of sound (audioslave) were duty-bound to visit and pay homage with their beater. The location is the volcanic island of Lanzarote, a truly remarkable place." – Storm Thorgerson[16]

An unreleased version of the cover, featuring a naked man looking at the flame, was shot elsewhere at the same location. "We so nearly used it," said Thorgerson, "but we were not entirely sure of the nude figure."[17]

Reception

[edit]Critical

[edit]| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 62/100[18] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | (favorable)[20] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[21] |

| NME | 4/10[22] |

| Pitchfork | 1.7/10[3] |

| Robert Christgau | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Stylus Magazine | F[4] |

Audioslave received mixed reviews from critics. Some critics lambasted the group's efforts as uninspired[21] and predictable.[25]

Pitchfork's reviewers Chris Dahlen and Ryan Schreiber praised Cornell's voice, but criticized virtually every other aspect of the album, calling it "the worst kind of studio rock album, rigorously controlled -- even undercut -- by studio gimmickry". They described Cornell's lyrics as "complete gibberish" and called producer Rick Rubin's work "a synthesized rock-like product that emits no heat".[3]

Jon Monks from Stylus Magazine also considered Rubin's production over-polished and wrote that, "lacking individuality, distinction and imagination this album is over-produced, overlong and over-indulgent".[4] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of Allmusic gave the album a mixed three stars out of a possible five, writing: "Occasionally, the group winds up with songs that play to the strengths of both camps," but more often "many of the songs sound like they're just on the verge of achieving liftoff, never quite reaching their potential."[19]

On the other hand, other critics praised the supergroup's style as reminiscent of 1970s heavy metal and compared it to Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath,[26][27] saying Audioslave add a much-needed sound and style to contemporary mainstream rock music[28] and have the potential to become one of the best rock bands of the 21st century.[29]

In 2005, Audioslave was ranked number 281 in Rock Hard magazine's book of The 500 Greatest Rock & Metal Albums of All Time.[30]

Commercial

[edit]The album entered the Billboard 200 chart at position number seven, after selling 162,000 copies in its first week.[31] It was certified gold by the RIAA less than a month after its release,[32] and by 2006 had achieved triple-platinum status.[33]

It is the most successful Audioslave album to date, having sold more than three million copies in the United States alone. The singles "Cochise", "Like a Stone", "Show Me How to Live", and "I Am the Highway" all reached the top ten of Billboard's Modern Rock Tracks chart, with "Like a Stone" reaching number one,[34] and those four, plus "What You Are", reached the top ten of the Mainstream Rock chart, with "Like a Stone" again reaching the top spot.[35]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics are written by Chris Cornell; all music is composed by Audioslave

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Cochise" | 3:42 |

| 2. | "Show Me How to Live" | 4:38 |

| 3. | "Gasoline" | 4:39 |

| 4. | "What You Are" | 4:09 |

| 5. | "Like a Stone" | 4:54 |

| 6. | "Set It Off" | 4:23 |

| 7. | "Shadow on the Sun" | 5:43 |

| 8. | "I Am the Highway" | 5:35 |

| 9. | "Exploder" | 3:26 |

| 10. | "Hypnotize" | 3:27 |

| 11. | "Bring Em Back Alive" | 5:29 |

| 12. | "Light My Way" | 5:03 |

| 13. | "Getaway Car" | 4:59 |

| 14. | "The Last Remaining Light" | 5:17 |

| Total length: | 1:05:26 | |

DualDisc version

[edit]The album was included among a group of 15 DualDisc releases that were test-marketed in two cities: Boston and Seattle. The DualDisc has the standard album on one side and bonus material on the other side. The DVD side of the Audioslave DualDisc featured the entire album in higher resolution 48 kHz sound, as well as some videos. The higher resolution DVD side of this disc has been called a demonstration-quality audiophile release.[36][37]

ConnecteD bonus track

[edit]For a limited time, the CD could be inserted into a CD-ROM drive and used to access the ConnecteD website. Here, the user was able to download bonus videos, interviews, photos, and a bonus track ("Give").

Personnel

[edit]- Audioslave

- Chris Cornell – vocals

- Tim Commerford – bass, backing vocals

- Brad Wilk – drums

- Tom Morello – guitars

- Production and design

- Produced by Rick Rubin; Co-Produced by Audioslave

- Mixed by Rich Costey

- Recorded by David Schiffman and Andrew Scheps

- Additional Engineering by John Burton, Floyd Reitsma, Thom Russo, and Andrew Scheps; Assisted by Chris Holmes and Darron Mora

- Digital Editing by Greg Fidelman, Thom Russo, and Andrew Scheps

- Album Production Coordinator/Wrangler: Lindsay Chase

- Mastered by Vlado Meller, Assisted by Steve Kadison

- Album Cover by Storm Thorgerson and Peter Curzon

- Art Direction by Storm Thorgerson; Assisted by Dan Abbott and Finlay Cowan

- "Flame" Logo by Peter Curzon

- Photography by Rupert Truman

- Band Photos by Danny Clinch

- Sculpture Made by Hothouse

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[68] | 3× Platinum | 210,000^ |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[69] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[70] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[71] | Gold | 15,850[71] |

| Germany (BVMI)[72] | Gold | 100,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[73] sales since 2009 |

Gold | 25,000‡ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[74] | 3× Platinum | 45,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[75] | Gold | 20,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[76] | Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[77] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ "Audioslave – Audioslave". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (June 10, 2005). "Audioslave - Out of Exile". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c Dahlen, Chris; Schreiber, Ryan (November 25, 2002). "Audioslave: Audioslave". Pitchfork. Condé Nast. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c Monks, Jon (September 1, 2003). "Audioslave - Audioslave". Stylus. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (January 31, 2003). "Audioslave - Audioslave". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Lee, Matt (December 2002). "Stoke & Staffordshire Music – Singles review". BBC. Archived from the original on October 31, 2004. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Moss, Corey; Parry, Heather. "Audioslave: Unshackled, Ready To Rage". MTV. Archived from the original on February 1, 2003. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ O'Brien, Clare. "Pushing Forward Back". Zero Magazine. September 7, 2005, Iss. 1.

- ^ Weiss, Neal (May 22, 2001). "Rage And Cornell To Enter Studio Next Week". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Sculley, Alan. "A Career in Slavery". San Diego CityBeat. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ D’Angelo, Joe (May 20, 2002). "Rage/Cornell-Credited Tracks Get Leaked Online". MTV. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Anderson, Donna (July 16, 2002). "20 Questions with… Rage Against The Machine Guitarist Tom Morello". Metal Sludge. Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Cashmere, Tim. "Audioslave to the Rhythm". Undercover. Archived from the original on September 2, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Ewing, Jerry (December 2002). "Straight Outta Rehab". Metal Hammer (108).

- ^ Levenfeld, Ari (April 13, 2003). "Audioslave: self-titled". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Thorgerson, Storm (March 2009). "Storm Thorgerson on Classic Sleeves". Classic Rock. No. 129. p. 22.

- ^ Classic Rock 2010 calendar

- ^ "Audioslave - Audioslave". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen. "Audioslave - Audioslave". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (December 6, 2002). "Audioslave: Audioslave". The A.V. Club. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Browne, David (November 22, 2002). "Audioslave Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Audioslave : Audioslave". NME. December 6, 2002. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "CG: audioslave". Robert Christgau. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Blashill, Pat (November 4, 2002). "Audioslave : Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Tate, Greg (January 14, 2003). "Village Voice Review". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ McAuliffe, Amy (June 21, 2007). "Rock/Indie Review – Audioslave, Audioslave". BBC. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Jeres (November 21, 2002). "Audioslave: Audioslave (2002) review". PlayLouder. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (January 31, 2003). "Music: Review - Audioslave Audioslave". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Heath, Chris (January 9, 2003). "Album Reviews: Audioslave - Audioslave". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Best of Rock & Metal - Die 500 stärksten Scheiben aller Zeiten (in German). Rock Hard. 2005. p. 102. ISBN 3-89880-517-4.

- ^ "Audioslave, Mudvayne Debut In Billboard's Top 20". Blabbermouth.net. November 27, 2002. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ "Audioslave Land Gold Album". Blabbermouth.net. December 17, 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Searchable Database - Search Results - Audioslave". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved August 25, 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Jerry Del Colliano[1] Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Audio Video Revolution, June 07, 2004

- ^ Jerry Del Colliano[2] Archived September 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Home Theater Review, March 22, 2010

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Audioslave – Audioslave" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Audioslave – Audioslave" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Eurochart Top 100 Albums - February 15, 2003" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 21, no. 8. February 15, 2003. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Audioslave: Audioslave" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Audioslave – Audioslave" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Audioslave – Audioslave". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Audioslave | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History (Top Alternative Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History (Top Hard Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Audioslave Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Top 200 Albums of 2002 (based on sales)". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on December 4, 2003. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Metal Albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "ARIA Charts - End Of Year Charts - Top 100 Albums 2003". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Charts 2003 – Official Top 40 Albums". Recorded Music New Zealand. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart 2003" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ Billboard 200 Albums (2004 Year-end) Archived October 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Billboard.com. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "The Decade in Music - Charts - Top Billboard 200 Albums" (PDF). Billboard. December 19, 2009. p. 164. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2021 – via World Radio History. Digit page 168 on the PDF archive.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2017 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave". Music Canada. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Audioslave" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Audioslave; 'Audioslave')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved May 1, 2020. Select "2020" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "Audioslave" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ "British album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "American album certifications – Audioslave – Audioslave". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 28, 2018.