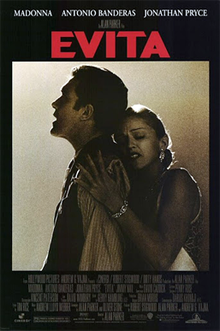

Evita (1996 film)

| Evita | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan Parker |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Evita by Tim Rice Andrew Lloyd Webber |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Darius Khondji |

| Edited by | Gerry Hambling |

| Music by | Andrew Lloyd Webber |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution (North America/South America/Spain) Cinergi Productions (International) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 134 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $55 million[3] |

| Box office | $141 million[3] |

Evita is a 1996 American biographical musical drama film based on the 1976 concept album of the same name produced by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, which also inspired a 1978 musical. The film depicts the life of Eva Perón, detailing her beginnings, rise to fame, political career and death at the age of 33. Directed by Alan Parker, and written by Parker and Oliver Stone, Evita stars Madonna as Eva, Jonathan Pryce as Eva's husband Juan Perón, and Antonio Banderas as Ché, an everyman who acts as the film's narrator.

Following the release of the 1976 album, a film adaptation of the musical became mired in development hell for more than fifteen years, as the rights were passed on to several major studios, and various directors and actors considered. In 1993, producer Robert Stigwood sold the rights to Andrew G. Vajna, who agreed to finance the film through his production company Cinergi Pictures, with Buena Vista Pictures distributing the film through Hollywood Pictures. After Stone stepped down from the project in 1994, Parker agreed to write and direct the film. Recording sessions for the songs and soundtrack took place at CTS Studios in London, England, roughly four months before filming. Parker worked with Rice and Lloyd Webber to compose the soundtrack, reworking the original songs by creating the music first and then the lyrics. They also wrote a new song, "You Must Love Me", for the film. Principal photography commenced in February 1996 with a budget of $55 million, and concluded in May of that year. Filming took place on locations in Buenos Aires and Budapest as well as on soundstages at Shepperton Studios. The film's production in Argentina was met with controversy, as the cast and crew faced protests over fears that the project would tarnish Eva's image.

Evita premiered at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, California, on December 14, 1996. Hollywood Pictures gave the film a platform release, which involved releasing it in select cities before expanding distribution in the following weeks. The film had a limited release on December 25, 1996, before opening nationwide on January 10, 1997. It grossed over $141 million worldwide. The film received a mixed critical response; reviewers praised Madonna's performance, the music, costume designs and cinematography, while criticism was aimed at the pacing and direction. Evita received many awards and nominations, including the Academy Award for Best Original Song ("You Must Love Me"), and three Golden Globe Awards for Best Picture – Comedy or Musical, Best Original Song ("You Must Love Me") and Best Actress – Comedy or Musical (Madonna).

Plot

[edit]At a cinema in Buenos Aires on July 26, 1952, a film is interrupted when news breaks of the death of Eva Perón, Argentina's First Lady, at the age of 33. As the nation goes into public mourning, Ché, a member of the public, marvels at the spectacle and promises to show how Eva did "nothing for years". The rest of the film follows Eva (née Duarte) from her beginnings as an illegitimate child of a lower-class family to her rise to become First Lady; Ché assumes many different guises throughout Eva's story.

At the age of 15, Eva lives in the provincial town of Junín, and longs for a better life in Buenos Aires. She persuades a tango singer, Agustín Magaldi, with whom she is having an affair, to take her to the city. After Magaldi leaves her, she goes through several relationships with increasingly influential men, becoming a model, actress and radio personality. She meets Colonel Juan Perón at a fundraiser following the 1944 San Juan earthquake. Perón's connection with Eva adds to his populist image, since they are both from the working class. Eva has a radio show during Perón's rise and uses all of her skills to promote him, even when the controlling administration has him jailed in an attempt to stunt his political momentum. The groundswell of support that Eva generates forces the government to release Perón, and he finds the people enamored of him and Eva. Perón wins election to the presidency and marries Eva, who promises that the new government will serve the descamisados.

At the start of the Perón government, Eva dresses glamorously, enjoying the privileges of being the First Lady. Soon after, she embarks on what is called her "Rainbow Tour" of Europe. While there, she receives a mixed reception. The people of Spain adore her, the people of Italy call her a whore and throw things at her, and Pope Pius XII gives her a small, meager gift. Upon returning to Argentina, Eva establishes a foundation to help the poor. The film suggests the Perónists otherwise plunder the public treasury.

Eva is hospitalized and learns that she has terminal cancer. She declines the position of Vice President due to her failing health, and makes one final broadcast to the people of Argentina. She understands that her life was short because she shone like the "brightest fire", and helps Perón prepare to go on without her. A large crowd surrounds the Unzué Palace in a candlelight vigil praying for her recovery when the light of her room goes out, signifying her death. At Eva's funeral, Ché is seen at her coffin, marveling at the influence of her brief life. He walks up to her glass coffin, kisses it, and joins the crowd of passing mourners.

Cast

[edit]- Madonna as Eva Perón

- Antonio Banderas as Ché

- Jonathan Pryce as Juan Perón

- Jimmy Nail as Agustín Magaldi

- Victoria Sus as Doña Juana Ibarguren

- Julian Littman as Juancito Duarte

- Olga Merediz as Bianca Duarte

- Laura Pallas as Elisa Duarte

- Julia Worsley as Erminda Duarte

- Peter Polycarpou as Domingo Mercante

- Gary Brooker as Juan Atilio Bramuglia

- Andrea Corr as Juan's mistress

- Alan Parker as Tormented film director

- Peter Hughes as General Francisco Franco

Cast taken from Turner Classic Movies listing of Evita.[4]

Production

[edit]Failed projects: 1976–1986

[edit]

Following the release of Evita (1976), a sung-through concept album by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber detailing the life of Eva Perón, director Alan Parker met with their manager David Land, asking if Rice and Lloyd Webber had thought of making a film version. He understood that they were more interested in creating a stage version with the album's original lyrics.[5] The original West End theatre production of Evita opened at the Prince Edward Theatre on June 21, 1978, and closed on February 18, 1986.[6] The subsequent Broadway production opened at the Broadway Theatre on September 25, 1979, and closed on June 26, 1983, after 1,567 performances and 17 previews.[7] Robert Stigwood, producer of the West End production, wanted Parker to direct Evita as a film but, after completing work on the musical Fame (1980), Parker turned down the opportunity to helm Evita, telling Stigwood that he "didn't want to do back-to-back musicals".[5]

The film rights to Evita became the subject of a bidding war among Warner Bros., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and Paramount Pictures.[8] Stigwood sold the rights to EMI Films for over $7.5 million. He also discussed the project with Jon Peters, who promised that he would convince his girlfriend Barbra Streisand to play the lead role if he were allowed to produce. Streisand, however, was not interested in the project because she saw the stage version in New York and didn't like it. Stigwood turned down the offer, opting to stay involved as the film's sole producer. EMI ultimately dropped the project after merging with Thorn Electrical Industries to form Thorn EMI, as well as producing several box-office flops under the banner.[9]

In May 1981, Paramount Pictures acquired the film rights, with Stigwood attached as a producer.[10][11] Paramount allocated a budget of $15 million, and the film was scheduled to go into production by year-end. To avoid higher production costs, Stigwood, Rice and Lloyd Webber each agreed to take a smaller salary but a higher percentage of the film's gross.[11] Stigwood hired Ken Russell to direct the film, based on the success of their previous collaboration Tommy (1975).[9]

Stigwood and Russell decided to hold auditions with the eight actresses portraying Eva in the musical's worldwide productions, with an undisclosed number performing screen tests in New York and London.[9] In November 1981, Russell continued holding screen tests at Elstree Studios. Karla DeVito was among those who auditioned for the role of Eva.[8] Russell also travelled to London, where he screen tested Liza Minnelli wearing a blonde wig and custom-period gowns. He felt that Minnelli, a more established film actress, would be better suited for the role, but Rice, Stigwood and Paramount wanted Elaine Paige, the first actress to play Eva in the London stage production.[8][9] Russell began working on his own screenplay without Stigwood, Rice or Lloyd Webber's approval. His script followed the outlines of the stage production, but established the character of Ché as a newspaper reporter. The script also contained a hospital montage for Eva and Ché, in which they pass each other on gurneys in white corridors as she is being treated for cancer, while Ché is beaten and injured by rioters.[8] Russell was ultimately fired from the project after telling Stigwood he would not do the film without Minnelli.[8][9][12]

As Paramount began scouting locations in Mexico, Stigwood began the search for a new director. He met with Herbert Ross, who declined in favor of directing Footloose (1984) for Paramount. Stigwood then met with Richard Attenborough, who deemed the project impossible.[9] Stigwood also approached directors Alan J. Pakula and Hector Babenco, who both declined.[9][12] In 1986, Madonna visited Stigwood in his office, dressed in a gown and 1940s-style hairdo to show her interest in playing Eva.[13] She also campaigned briefly for Francis Ford Coppola to helm the film.[8] Stigwood was impressed, stating that she was "perfect" for the part.[13]

Oliver Stone: 1987–1994

[edit]

In 1987, Jerry Weintraub's independent film company Weintraub Entertainment Group (WEG) obtained the film rights from Paramount.[12][14][15] Oliver Stone, a fan of the musical, expressed interest in the film adaptation and contacted Stigwood's production company RSO Films to discuss the project. After he was confirmed as the film's writer and director in April 1988, Stone travelled to Argentina, where he visited Eva's birthplace and met with the newly elected President Carlos Menem, who agreed to provide 50,000 extras for the production as well as allowing freedom of speech.[12]

Madonna met with Stone and Lloyd Webber in New York to discuss the role. Plans fell through after she requested script approval and told Lloyd Webber that she wanted to rewrite the score.[13] Stone then approached Meryl Streep for the lead role and worked closely with her, Rice and Lloyd Webber at a New York City recording studio to do preliminary dubbings of the score. Stigwood said of Streep's musical performance: "She learned the entire score in a week. Not only can she sing, but she's sensational – absolutely staggering."[9]

WEG allocated a budget of $29 million, with filming set to begin in early 1989, but production was halted due to the 1989 riots in Argentina. Concerned for the safety of the cast and crew, Stigwood and Weintraub decided against shooting there. The filmmakers then scouted locations in Brazil and Chile, before deciding on Spain, with a proposed budget of $35 million; the poor box office performances of WEG's films resulted in the studio dropping the project.[12] Stone took Evita to Carolco Pictures shortly after, and Streep remained a front-runner for the lead role. However, Streep began increasing her compensation requests; she demanded a pay-or-play contract with a 48-hour deadline. Although an agreement was reached, Streep's agent contacted Carolco and RSO Films, advising them that she was stepping down from the project for "personal reasons". Streep renewed her interest after 10 days, but Stone and his creative team had left the project in favor of making The Doors (1991).[12]

In 1990, the Walt Disney Studios acquired the film rights to Evita, and Glenn Gordon Caron was hired to direct the film, with Madonna set to appear in the lead role. Disney was to produce the film under its film label Hollywood Pictures. Although Disney had spent $2–3 million in development costs, it canceled the plans in May 1991 when the budget climbed to $30 million. Disney chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg did not want to spend more than $25.7 million on the film.[16][17] In November 1993, Stigwood sold the film rights to Andrew G. Vajna's production company Cinergi Pictures.[16][18] Vajna later enlisted Arnon Milchan of Regency Enterprises as a co-financier, and Stone returned as the film's director after meeting with Dan Halsted, the senior vice president of Hollywood Pictures. Production was set to begin sometime in 1995 after Stone and Milchan concluded filming of Noriega, a film chronicling the life of Panamanian general and dictator Manuel Noriega.[16] Stone and Milchan disputed over the high production costs of Evita, Noriega (which never was filmed) and Nixon (1995),[19] resulting in Stone leaving the project in July 1994.[10]

Development

[edit]

In December 1994, Alan Parker signed on to write and direct the film after being approached by Stigwood and Vajna.[5] Parker also produced the film, with his Dirty Hands Productions banner enlisted as a production company.[1] While drafting his own script, Parker researched Eva's life, compiling newspaper articles, documentaries and English-language books. He refused to borrow elements from Stone's script or the stage play, instead opting to model his script after Rice and Lloyd Webber's concept album.[5][13] Stone had a falling out with Parker over the content of the script, claiming that he had made significant contributions. A legal dispute and arbitration by the Writers Guild of America resulted in Parker and Stone sharing a screenwriting credit.[20]

"While Evita is a story of people whose lives were in politics, it is not a political story. It is a Cinderella story about the astonishing life of a girl from the most mundane of backgrounds, who became the most powerful woman her country (and indeed Latin America) had ever seen, a woman never content to be a mere ornament at the side of her husband, the president."

— Alan Parker, writer and director[21]

Parker's finished script included 146 changes to the concept album's music and lyrics.[5] In May 1995, he and Rice visited Lloyd Webber at his home in France, where Parker tried to bring them to work on the film. Rice and Lloyd Webber had not worked together for many years, and the script for Evita required that they compose new music.[5] In June 1995, with assistance from the United States Department of State and United States Senator Chris Dodd, Parker arranged a private meeting with Menem in Argentina to discuss the film's production and request permission to film at the Casa Rosada, the executive mansion.[5] Although he expressed his discontent with the production,[5] Menem granted the filmmakers creative freedom to shoot in Argentina, but not in the Casa Rosada. He also advised Parker to be prepared to face protests against the film.[22] Parker had the film's production designer Brian Morris take photographs of the Casa Rosada, so that the production could construct a replica at Shepperton Studios in England. The director visited seven other countries before deciding to film on location in Buenos Aires and Budapest.[5]

Casting

[edit]Antonio Banderas was the first actor to secure a role in the film. He was cast as Ché when Glenn Gordon Caron was hired to direct the film,[23] and remained involved when Stone returned to the project.[23][24] Before he left the project, Stone had considered casting Michelle Pfeiffer in the lead role of Eva,[8] and this was confirmed in July 1994.[24] Pfeiffer left the production when she became pregnant with her second child. Parker also considered Glenn Close, along with Meryl Streep, to play Eva.[25]

In December 1994, Madonna sent Parker a copy of her "Take a Bow" music video along with a four-page letter explaining that she was the best person to portray Eva and would be fully committed to the role.[5][26] Parker insisted that if Madonna was to be his Evita, she must understand who was in charge. "The film is not a glorified Madonna video," said Parker. "I controlled it and she didn't."[27] Rice believed that Madonna suited the title role since she could "act so beautifully through music".[28] Lloyd Webber was wary about her singing. Since the film required the actors to sing their own parts, Madonna underwent vocal training with coach Joan Lader to increase her own confidence in singing the unusual songs, and project her voice in a much more cohesive manner.[28][29] Lader noted that the singer "had to use her voice in a way she's never used it before. Evita is real musical theater — it's operatic, in a sense. Madonna developed an upper register that she didn't know she had."[30][31]

In January 1996, Madonna travelled to Buenos Aires to research Eva's life, and met with several people who had known her before her death.[31] During filming, she fell sick many times due to the intense emotional effort required,[32] and midway through production, she discovered she was pregnant. Her daughter Lourdes was born on October 14, 1996. Madonna published a diary of the film shoot in Vanity Fair.[33] She said of the experience, "This is the role I was born to play. I put everything of me into this because it was much more than a role in a movie. It was exhilarating and intimidating at the same time ... And I am prouder of Evita than anything else I have done."[34]

Parker decided to keep Banderas in the supporting role of Ché after checking the actor's audition tape.[23] While writing the script, the director chose not to identify the character with Ernesto "Che" Guevara, which had been done in several versions of the musical.[35] "In the movie Ché tells the story of Eva", Banderas said. "He takes a very critical view of her and he's sometimes cynical and aggressive but funny, too. At the same time he creates this problem for himself because, for all his principles, he gets struck by the charm of the woman."[23] For the role of Juan Perón, Parker approached film and stage actor Jonathan Pryce, who secured the part after meeting with the director.[5]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography

[edit]The film's production in Argentina was met with controversy and sparked significant media attention. The cast and crew faced protests over fears that the project would tarnish Eva's image.[5][31][33] Members of the Peronist Party launched a hate campaign, condemning the film's production, Madonna and Parker.[5] Evita also prompted the government of Argentina to produce its own film, Eva Perón: The True Story (1996), to counter any misconceptions or inaccuracies caused by the film.[36] In response to the controversy surrounding the project, the production held a press conference in Buenos Aires on February 6, 1996.[37]

Principal photography began on February 8, 1996,[5][37] with a budget of $55 million.[3] Production designer Brian Morris constructed 320 different sets.[5][13] Costume designer Penny Rose was given special access to Eva's wardrobe in Argentina, and she modeled her own costume designs after Eva's original outfits and shoes.[1] She clothed 40,000 extras in period dresses. The production used more than 5,500 costumes from 20 costume houses located in Paris, Rome, London, New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Buenos Aires, and Budapest as well as 1,000 military uniforms. Madonna's wardrobe included 85 costume changes, 39 hats, 45 pairs of shoes, and 56 pairs of earrings.[5] She broke the Guinness World Record for "Most Costume Changes in a Film".[38]

Filming began in Buenos Aires with scenes depicting Eva's childhood in 1936. Locations included Los Toldos, the town of Junín, where Eva was raised, and Chivilcoy, where her father's funeral was held.[5] On February 23, 1996, Menem arranged a meeting with Parker, Madonna, Pryce and Banderas,[5][31] and granted the crew permission to film in the Casa Rosada shortly before they were scheduled to leave Buenos Aires.[13] On March 9, the production filmed the musical number "Don't Cry for Me Argentina" there, utilizing 4,000 extras for two days. Filming in Buenos Aires concluded after five weeks.[5][39]

The cast and crew then moved to Budapest, Hungary, where 23 locations were used for scenes set in Buenos Aires.[40] The production spent two days re-enacting Eva's state funeral, which required 4,000 extras to act as citizens, police officials and military personnel.[5] The filmmakers shot exterior scenes outside of the St. Stephen's Basilica, but were denied access to film inside the building.[5][41] For the musical numbers "Your Little Body's Slowly Breaking Down" and "Lament", Parker had Madonna and Pryce record the songs live on set, due to the emotional effort required from their performances.[13] After five weeks of shooting in Hungary, the remainder of filming took place on sound stages at Shepperton Studios in England. Principal photography concluded on May 30, 1996 after 84 days of filming.[5][36]

Cinematography

[edit]Director of photography Darius Khondji was initially reluctant about working on a musical but was inspired by Parker's passion for the project.[42] For the film's visual style, Khondji and Parker were influenced by the works of American realist painter George Bellows.[43] Khondji shot Evita using Moviecam cameras, with Cooke anamorphic lenses. He used Eastman EXR 5245 film stock for exteriors in Argentina, 5293 for the Argentinean interiors, and 5248 for any scenes shot during overcast days and combat sequences.[44]

Khondji employed large tungsten lighting units, including 18K HMIs, dino and Wendy lights.[44] He used Arriflex's VariCon, which functions as an illuminated filter, and incorporated much more lens filtration than he had on previous projects. Technicolor's ENR silver retention, when combined with the VariCon, was used to control the contrast and black density of the film's release prints.[44] The finished film features 299 scenes and 3,000 shots from 320,000 feet (98,000 m) of film.[5]

Music and soundtrack

[edit]

Recording sessions for the film's songs and soundtrack began on October 2, 1995, at CTS Studios in London.[5][21] It took almost four months to record all the songs,[28] which involved creating the music first and then the lyrics.[5] Parker declared the first day of recording as "Black Monday",[5] and recalled it as a worrisome and nervous day. He said, "All of us came from very different worlds—from popular music, from movies, and from musical theater—and so we were all very apprehensive."[29] The cast was also nervous; Banderas found the experience "scary", while Madonna was "petrified" when it came to recording the songs. "I had to sing 'Don't Cry for Me Argentina' in front of Andrew Lloyd Webber ... I was a complete mess and was sobbing afterward. I thought I had done a terrible job", the singer recalled.[29][45]

According to the film's music producer Nigel Wright, the lead actors would first sing the numbers backed by a band and orchestra before working with Parker and music supervisor David Caddick "in a more intimate recording environment [to] perfect their vocals".[46] More trouble arose as Madonna was not completely comfortable with "laying down a guide vocal simultaneously with an 84-piece orchestra" in the studio. She was used to singing over a pre-recorded track and not having musicians listen to her. Also, unlike her previous soundtrack releases, she had little to no creative control. "I'm used to writing my own songs and I go into a studio, choose the musicians and say what sounds good or doesn't ... To work on 46 songs with everyone involved and not have a big say was a big adjustment," she recalled.[47] An emergency meeting was held between Parker, Lloyd Webber and Madonna, where it was decided that the singer would record her part at Whitfield Street Studios, a contemporary studio, while the orchestration would take place elsewhere. She also had alternate days off from the recording to preserve and strengthen her voice.[5][48]

By the end of recording, Parker noticed that Rice and Lloyd Webber did not have a new song in place. They arranged a meeting at Lloyd Webber's county estate in Berkshire, where they began work on the music and lyrics for "You Must Love Me".[5] Madonna's reaction to the lyrics was negative since she wanted Eva to be portrayed sympathetically, rather than as the "shrewd manipulator" that Parker had in mind. Although Madonna was successful in getting many portions in the script altered, Rice declined to change the song. He recalled, "I remember taking the lyrics to Madonna and she was trying to change them... The scene can be interpreted in different ways, but my lyrics were kept, thank God!"[49]

The soundtrack for Evita was released in the United States on November 12, 1996.[29] Warner Bros. Records released two versions: a two-disc edition entitled Evita: The Complete Motion Picture Music Soundtrack, which featured all the tracks from the film,[50] and Evita: Music from the Motion Picture, a single-disc edition.[51] AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine described the soundtrack as "unengaging",[52] while Hartford Courant's Greg Morago praised Madonna's singing abilities.[53] The soundtrack was a commercial success, reaching number one in Austria, Belgium, Scotland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom,[54][55][56] as well as selling over seven million copies worldwide.[57]

Release

[edit]

In May 1996, Parker constructed a 10-minute trailer of Evita that was shown at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival for reporters, film distributors and critics.[58][59] Despite a minor technical issue with the film projector's synchronization of the sound and picture,[60] the trailer received positive response.[61] Roger Ebert, for the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote "If the preview is representative of the finished film, Argentina can wipe away its tears."[60] Barry Walters of The San Francisco Examiner stated "Rather than showing the best moments from every scene, the trailer concentrates on a few that prove what Madonna, Banderas and Pryce can do musically. The results are impressive."[61] Evita premiered at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles on December 14, 1996,[62] the Savoy Cinema in Dublin, Ireland, on December 19, 1996, and the Empire Theatre in London on December 20, 1996.[63]

Hollywood Pictures gave the film a platform release, showing it in a few cities before expanding distribution in the following weeks. Evita opened in limited release in New York and Los Angeles on December 25, 1996, before being released nationwide on January 10, 1997.[1][62] The film was distributed by Buena Vista Pictures in North America and Latin America. Cinergi handled distribution in other countries, with Paramount Pictures releasing the film in Germany and Japan (through United International Pictures), Summit Entertainment in other regions[1][64] and Entertainment Film Distributors in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[2] A book detailing the film's production, The Making of Evita, was written by Parker and released on December 10, 1996 by Collins Publishers.[1] In 2002, Evita became the first and only American film to be screened at the Pyongyang International Film Festival.[65]

Home media

[edit]Evita was released on VHS on August 5, 1997,[66][67] and on LaserDisc on August 20, 1997.[68] A DTS LaserDisc version and a "Special Edition" LaserDisc by the Criterion Collection were both released on September 17, 1997.[69][70] Special features on the Criterion LaserDisc include an audio commentary by Parker, Madonna's music videos for "Don't Cry for Me Argentina" and "You Must Love Me", two theatrical trailers and five TV spots.[71] The film was released on DVD on March 25, 1998.[72] A 15th Anniversary Edition was released on Blu-ray on June 19, 2012.[73] The Blu-ray presents the film in 1080p high definition, and features a theatrical trailer, the music video for "You Must Love Me" and a behind-the-scenes documentary entitled "The Making of Evita".[71]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Evita grossed $71,308 on its first day of limited release, an average of $35,654 per theater.[74] By the end of its first weekend, the film had grossed $195,085, with an overall North American gross of $334,440.[75] More theatres were added on the following weekend, and the film grossed a further $1,064,660 in its second weekend, with an overall gross of $2,225,737.[75]

Released to 704 theaters in the United States and Canada, Evita grossed $2,551,291 on its first day of wide release.[74] By the end of its opening weekend, it had grossed $8,381,055, securing the number two position at the domestic box office behind the science-fiction horror film The Relic.[75][76] Evita saw a small increase in attendance in its second weekend of wide release. During the four-day Martin Luther King Jr. Day weekend, the film moved to third place on domestic box office charts, and earned $8,918,183—a 6.4% overall increase from the previous weekend.[75][77] It grossed another $5,415,891 during its fourth weekend, moving to fifth place in the top 10 rankings. Evita moved to fourth place the following weekend, grossing a further $4,374,631—a 19.2% decrease from the previous weekend. By its sixth weekend, the film moved from fourth to sixth place, earning $3,001,066.[75]

Evita completed its theatrical run in North America on May 8, 1997, after 135 days (19.3 weeks) of release.[3] It grossed $50,047,179 in North America, and $91,000,000 in other territories, for a worldwide total of $141,047,179.[3]

Critical response

[edit]Evita received a mixed response from critics.[78] Rotten Tomatoes sampled 39 reviews, and gave the film a score of 64%, with an average score of 6.7/10. The site's consensus reads: "Evita sometimes strains to convince on a narrative level, but the soundtrack helps this fact-based musical achieve a measure of the epic grandeur to which it aspires."[79] Another review aggregator, Metacritic, assigned the film a weighted average score of 45 out of 100 based on 23 reviews from critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[80]

Writing for the Hartford Courant, Malcolm Johnson stated "Against all odds, this long-delayed film version turns out to be a labor of love for director Alan Parker and for his stars, the reborn Madonna, the new superstar Antonio Banderas, the protean veteran Jonathan Pryce."[81] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars, writing "Parker's visuals enliven the music, and Madonna and Banderas bring it passion. By the end of the film we feel like we've had our money's worth, and we're sure Evita has."[82] On the syndicated television program Siskel & Ebert & the Movies, Ebert and his colleague Gene Siskel gave the film a "two thumbs up" rating.[83] Siskel, in his review for the Chicago Tribune, wrote, "Director Alan Parker has mounted this production well, which is more successful as spectacle than anything else."[84] According to Time magazine's Richard Corliss, "This Evita is not just a long, complex music video; it works and breathes like a real movie, with characters worthy of our affection and deepest suspicions."[85] Critic Zach Conner commented, "It's a relief to say that Evita is pretty damn fine, well-cast, and handsomely visualized. Madonna once again confounds our expectations. She plays Evita with a poignant weariness and has more than just a bit of star quality. Love or hate Madonna-Eva, she is a magnet for all eyes."[86]

Carol Buckland of CNN considered that "Evita is basically a music video with epic pretensions. This is not to say it isn't gorgeous to look at or occasionally extremely entertaining. It's both of those things. But for all the movie's grand style, it falls short in terms of substance and soul."[87] Newsweek's David Ansen wrote "It's gorgeous. It's epic. It's spectacular. But two hours later, it also proves to be emotionally impenetrable."[13] Giving the film a C− rating, Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly criticized Parker's direction, stating, "Evita could have worked had it been staged as larger-than-life spectacle ... The way Alan Parker has directed Evita, however, it's just a sluggish, contradictory mess, a drably "realistic" Latin-revolution music video driven by a soundtrack of mediocre '70s rock."[88] Janet Maslin from The New York Times praised Madonna's performance as well as the costume design and cinematography, but wrote that the film was "breathless and shrill, since Alan Parker's direction shows no signs of a moral or political compass and remains in exhausting overdrive all the time."[89] Jane Horwitz of the Sun-Sentinel stated, "Madonna sings convincingly and gets through the acting, but her performance lacks depth, grace and muscle. Luckily, director Alan Parker's historic-looking production with its epic crowd scenes and sepia-toned newsreels shows her off well."[90] Negative criticism came from the San Francisco Chronicle's Barbara Shulgasser, who wrote: "This movie is supposed to be about politics and liberation, the triumph of the lower classes over oppression, about corruption. But it is so steeped in spectacle, in Madonna-ness, in bad rock music and simple-minded ideas, that in the end it isn't about anything".[91]

Accolades

[edit]Evita received various awards and nominations, with particular recognition for Madonna, Parker, Rice, Lloyd Webber and the song "You Must Love Me". It received five Golden Globe Award nominations,[92] and won three for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, Best Actress – Musical or Comedy (Madonna) and Best Original Song ("You Must Love Me").[93] At the 69th Academy Awards, the film won the Academy Award for Best Original Song ("You Must Love Me"), and was nominated in four other categories: Best Film Editing, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction and Best Sound.[94] Madonna appeared during the Academy Awards and performed "You Must Love Me".[95] The National Board of Review named Evita one of the "Top 10 Films of 1996", ranking it at number four.[96] At the 50th British Academy Film Awards, Evita garnered eight nominations, but did not win in any category.[97] At the 1st Golden Satellite Awards, it received five nominations, and won three for Best Film, Best Original Song ("You Must Love Me"), and Best Costume Design (Penny Rose).[98]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "About the Filmmakers". Universal Studios. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ a b "Evita (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. December 13, 1996. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Evita (1996)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ "Evita (1996) – Full Credits". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Parker, Alan. "Evita – Alan Parker – Director, Writer, Producer – Official Website". AlanParker.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Evita at Prince Edward Theatre". ThisisTheatre.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "'Evita' listing, 1979–1983". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stoddard, Sylvia. "Oh What a Circus". SquareOne.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, Peter H. (March 5, 1989). "Desperately Seeking Evita". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Newsweek Staff (July 31, 1994). "Hasta La Vista, Baby". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (May 15, 1981). "Movie Rights to 'Evita' Bought by Paramount". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenberg, James (November 19, 1989). "Is It Time Now to Cry for 'Evita'?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ansen, David (December 15, 1996). "Madonna Tangos with Evita". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Oliver Stone To Start On Big-screen 'Evita'". New York Daily News. October 9, 1987. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Weintraub Entertainment and RSO reached a pact". Los Angeles Times. March 27, 1987. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c Eller, Claudia (December 11, 1993). "Crying's Over, 'Evita' Finds Backers : Movies: Disney plans to make the musical about Argentina's First Lady with the help of two investors and director Oliver Stone". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Fox, David J. (May 10, 1991). "'Evita' Film Once More in Limbo". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Gritten, David (May 4, 1996). "'She'll Surprise a Lot of People". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Busch, Anita M. (February 19, 1995). "Oliver Stone, New Regency On The Rocks?". Variety. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Hamburg 2002, p. 232

- ^ a b Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, p. 235

- ^ Bona, Damien (2002). "Hey There, Lonely Girl". Inside Oscar 2. United States: Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-44800-2.

- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Michael (December 21, 1996). "Che New". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Villacorta, Francis O. (July 5, 1994). "Michelle Pfeiffer is Webber's 'Evita'". Manila Standard. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Cross 2007, p. 67

- ^ Palomino, Erika (September 26, 1996). "MTV mostra Madonna nos bastidores do filme 'Evita'" [MTV shows Madonna behind the scenes of the film 'Evita']. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Ansen, David (December 15, 1996). "Madonna Tangos With Evita". Newsweek. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c O'Brien 2008, pp. 305–306

- ^ a b c d Flick 1996, p. 91

- ^ Taraborrelli 2008, p. 260

- ^ a b c d Ciccone, Madonna (November 1996). "The Madonna Diaries". Vanity Fair. pp. 174–188. ASIN B001BVYGJS. ISSN 0733-8899.

- ^ Taraborrelli 2008, p. 276

- ^ a b "Mad for Evita". Time. December 30, 1996. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ St. Michael 2004, p. 67

- ^ Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, p. 234

- ^ a b Gonthier & O'Brien 2015, p. 236

- ^ a b Cerio, Gregory (February 26, 1996). "Don't Yell at Me, Argentina". People. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Guinness World Records 2000. Jim Pattison Group. 2000. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-606-17606-4.

- ^ Dwyer, Michael (May 5, 1996). "Film; Don't Cry for the New Eva Either". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Marsh, Virginial (April 4, 1996). "Budapest Girds For Traffic Jams As It Greets Cash-cow 'Evita'". Deseret News. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Sophie (January 24, 1997). "Where the Camera Lies". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Ettedgui 1998, p. 194

- ^ Ettedgui 1998, p. 199

- ^ a b c "Exemplary Images". American Society of Cinematographers. June 1997. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Sandi (August 31, 2016). "Banderas Sings Praises of 'Evita'". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Soundtrack of 'Evita'". Universal Studios. Archived from the original on December 6, 1999. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Taraborrelli 2008, p. 261

- ^ Taraborrelli 2008, p. 262

- ^ O'Brien 2008, pp. 308

- ^ "Evita [Motion Picture Music Soundtrack]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ "Evita: Music from the Motion Picture Soundtrack CD Album". CD Universe. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Evita". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Morago, Greg (November 14, 1996). "Album Review – Motion Picture Soundtrack – Evita". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Soundtrack / Madonna – Evita" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Hits of the World: Eurochart" (PDF). Billboard. February 15, 1997. p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna | Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. January 14, 1984. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "Madonna, ritorno a ritmo di "techno"" (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). January 23, 1998. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "An Interview with Alan Parker". Universal Studios. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (May 31, 1996). "Cannes Film Festival has stars, movies, and nudity". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (May 15, 1996). "Promising Preview Builds 'Evita' Buzz". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Walters, Barry (July 10, 1996). "Madonna Rules. Sounds As Good As She Looks". The San Francisco Examiner.

- ^ a b "Sir Tim Rice—Evita". Tim Rice Official website. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Harrison, Bernice (December 20, 1996). "'Evita' stars appear on a 20-foot screen". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (May 16, 1996). "Changes to Evita Film Score". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ Schönherr 2012, p. 12

- ^ "'Murder at 1600,' 'Booty Call' among newest video releases". The Kansas City Star. August 8, 1997. p. 106. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved April 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Evita VHS release (Media notes) (in German). August 21, 1997. ASIN B00004RTML.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database – Evita [11853 AS]". LaserDisc Database. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database – Evita: Special Edition [CC1488L]". LaserDisc Database. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database – Evita [12096 AS]". LaserDisc Database. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "Evita Blu-ray Review". DVDizzy.com. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "DVD: Evita (DVD) with Antonio Banderas, Gary Brooker, Adrià Collado, Andrea Corr, Martin Drogo". Tower Records. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Evita Blu-ray: 15th Anniversary Edition". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "Evita (1996) – Daily Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Evita (1996) – Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 10–12, 1997". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 17–20, 1997". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Dominguez, Robert (January 14, 1997). "Madonna's Hot Ticket: 'Evita' Close to No. 1 But Will Strong Box Office Get Material Girl Into H'wood Groove?". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Evita (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Evita Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Malcolm (January 10, 1997). "Madonna Gives Soul to Screen Incarnation Of 'Evita'". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 3, 1997). "Evita Movie Review & Film Summary (1997)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (December 21, 1996). Siskel & Ebert & the Movies.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (January 3, 1997). "Madonna Stands Up To 'Evita' Demands". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 16, 1996). "Cinema: Madona and Eva Peron: You Must Love Her". Time. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Taraborrelli 2008, p. 285

- ^ Buckland, Carol (January 4, 1997). "'Evita' Tailor-made for Madonna". CNN. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (December 20, 1996). "Evita". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 25, 1996). "Madonna, Chic Pop Star as Chic Political Star". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Horwitz, Jane (January 10, 1997). "Evita". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Shulgasser, Barbara (January 1, 1997). "Evita' eviscerated". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ "'English Patient' Leads Golden Globe Nominations". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 20, 1996. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1997". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Copeland, Jeff (February 12, 1997). "Madonna Will Sing at the Oscars". E! News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ "1996 Archives – National Board of Review". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards Search Box: Put 'Evita' and click". British Academy Film Awards. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ Errico, Marcus (January 15, 1997). "Cruise Tops Golden Satellite Awards". E! News. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Clerk, Carol (2008). Madonna Style. Music Sales Group. ISBN 978-0-85712-218-6.

- Cross, Mary (2007). "7. Reinvention". Madonna: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33811-3.

- Ettedgui, Peter (1998). Cinematography. Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-80382-1.

- Flick, Larry (October 26, 1996). "Radio embraces Madonna's "Evita"". Billboard. Vol. 108, no. 43. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Gonthier, David F. Jr.; O'Brien, Timothy L. (2015). "13. Evita, 1996". The Films of Alan Parker, 1976–2003. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9725-6.

- Hamburg, Eric (2002). "The First Draft". Jfk, Nixon, Oliver Stone and Me: An Idealist's Journey from Capitol Hill to Hollywood Hell. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-037-8.

- O'Brien, Lucy (2008). Madonna: Like an Icon. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-552-15361-4.

- Schönherr, Johannes (2012). North Korean Cinema: A History. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-6526-2.

- St. Michael, Mick (2004). Madonna Talking: Madonna in Her Own Words. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-418-7.

- Taraborrelli, Randy J. (2008). Madonna: An Intimate Biography. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-330-45446-9.

External links

[edit]- Evita at AlanParker.com

- Evita at IMDb

- Evita at the TCM Movie Database

- Evita at Box Office Mojo

- Evita at Rotten Tomatoes

- Evita at Metacritic

- 1996 films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s musical drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- American biographical drama films

- American musical drama films

- Musicals by Andrew Lloyd Webber

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- Biographical films about actors

- Cinergi Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Eva Perón

- Cultural depictions of Pope Pius XII

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on albums

- Films based on musicals

- Films directed by Alan Parker

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films produced by Andrew G. Vajna

- Films produced by Robert Stigwood

- Films set in Argentina

- Films set in South America

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- Films shot in Argentina

- Films shot in Budapest

- Films shot in Buenos Aires

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Hollywood Pictures films

- Musical films based on actual events

- Films with screenplays by Alan Parker

- Films with screenplays by Oliver Stone

- 1990s Spanish-language films

- Sung-through musical films

- 1996 drama films

- 1990s American films

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language musical drama films

- 1996 musical films