Ethan Hawke

Ethan Hawke | |

|---|---|

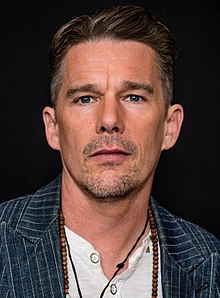

Hawke at the 2018 Montclair Film Festival | |

| Born | Ethan Green Hawke November 6, 1970 Austin, Texas, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1985–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4, including Maya and Levon Hawke |

| Awards | Full list |

Ethan Green Hawke (born November 6, 1970) is an American actor, author, and film director. He made his film debut in Explorers (1985), before making a breakthrough performance in Dead Poets Society (1989). Hawke starred alongside Julie Delpy in Richard Linklater's Before trilogy from 1995 to 2013. Hawke received two nominations for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for Training Day (2001) and Boyhood (2014) and two for Best Adapted Screenplay for co-writing Before Sunset (2004) and Before Midnight (2013). Other notable roles include in Reality Bites (1994), Gattaca (1997), Great Expectations (1998), Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007), Maggie's Plan (2015), First Reformed (2017), The Black Phone (2021), and The Northman (2022).

Hawke directed the narrative films Chelsea Walls (2001), The Hottest State (2006), and Blaze (2018) as well as the documentary Seymour: An Introduction (2014). He created, co-wrote and starred as John Brown in the Showtime limited series The Good Lord Bird (2018), and directed the HBO Max documentary series The Last Movie Stars (2022). He starred in the Marvel television miniseries Moon Knight (2022) as Arthur Harrow.

In addition to his film work, Hawke has appeared in many theater productions. He made his Broadway debut in 1992 in Anton Chekhov's The Seagull, and was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Play in 2007 for his performance in Tom Stoppard's The Coast of Utopia. In 2010, Hawke directed Sam Shepard's A Lie of the Mind, for which he received a Drama Desk Award nomination for Outstanding Director of a Play. In 2018, he starred in the Roundabout Theater Company's revival of Sam Shepard's play True West.

He has received numerous nominations including a total of four Academy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, and a Tony Award.

Early life

Hawke was born on November 6, 1970[1][2] to Leslie (née Green), a charity worker, and James Hawke, an insurance actuary.[3][4] Hawke's parents were high school sweethearts in Fort Worth, Texas, and married young, when Hawke's mother was 17.[5] Hawke was born a year later. Hawke's parents were both students at the University of Texas at Austin at the time of his birth. They separated and later divorced in 1974, when he was four years old.[3][6]

After the separation, Hawke was raised by his mother. The two relocated several times, before settling in New York City, where Hawke attended the Packer Collegiate Institute in Brooklyn Heights.[7] Hawke's mother remarried when he was 10 and the family moved to West Windsor Township, New Jersey.[8] There, Hawke attended the public West Windsor Plainsboro High School (renamed to West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South in 1997).[6][7] He later transferred to the Hun School of Princeton, a secondary boarding school,[9] from which he graduated in 1988.[10]

In high school, Hawke aspired to be a writer, but developed an interest in acting. He made his stage debut at age 13, in a production at the McCarter Theatre of George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan.[7][11] He also performed in West Windsor-Plainsboro High School productions of Meet Me in St. Louis and You Can't Take It with You.[12] At the Hun School, he took acting classes at the McCarter Theatre, located on the Princeton campus.[12] After graduation from high school, he studied acting at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, dropping out after he was cast in Dead Poets Society (1989).[13] He enrolled in New York University's English program for two years, but dropped out to pursue other acting roles.[11]

Career

1980s: Early years and Dead Poets Society

Hawke obtained his mother's permission to attend his first casting call at the age of 14,[14] and secured his first film role in Joe Dante's Explorers (1985), in which he played an alien-obsessed schoolboy alongside River Phoenix.[15] The film was favorably reviewed[16] but had poor box office results. This failure caused Hawke to quit acting for a brief period after the film's release.[13] Hawke later described the disappointment as difficult to bear at such a young age, adding, "I would never recommend that a kid act."[13]

In 1989, Hawke made his breakthrough appearance in Peter Weir's Dead Poets Society, playing one of the students taught by Robin Williams as a charismatic English teacher.[6] The Variety reviewer noted "Hawke, as the painfully shy Todd, gives a haunting performance."[17] The film received considerable acclaim,[18] winning the BAFTA Award for Best Film and an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture.[19][20] With revenue of $235 million worldwide, it remains Hawke's most commercially successful movie to date.[21] Hawke later described the opportunities he was offered as a result of the film's success as critical to his decision to continue acting:

I didn't want to be an actor and I went back to college. But then the [film's] success was so monumental that I was getting offers to be in such interesting movies and be in such interesting places, and it seemed silly to pursue anything else.[14]

While filming Dead Poets Society he auditioned for what would be his next film, 1989's comedy drama Dad, where he played Ted Danson's son and Jack Lemmon's grandson.[13] Hawke's next film, 1991's White Fang, brought his first leading role. The film, an adaptation of Jack London's novel of the same name, featured Hawke as Jack Conroy, a Yukon gold hunter who befriends a wolfdog (played by Jed). According to The Oregonian, "Hawke does a good job as young Jack ... He makes Jack's passion for White Fang real and keeps it from being ridiculous or overly sentimental."[22] He appeared in Keith Gordon's A Midnight Clear (1992), a well-received war film based on William Wharton's novel of the same name.[23] In the survival drama Alive (1993), adapted from Piers Paul Read's 1974 non-fiction book, Hawke portrayed Nando Parrado, one of the survivors of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, which crashed in the Andes.[24]

1990s: Reality Bites, and Before Sunrise

Hawke's next role was in the Generation X drama Reality Bites (1994), in which he played Troy Dyer, a slacker who mocks the ambitions of his girlfriend (played by Winona Ryder). Film critic Roger Ebert called Hawke's performance convincing and noteworthy: "Hawke captures all the right notes as the boorish Troy (and is so convincing it is worth noting that he has played quite different characters equally well in movies as different as "Alive" and "Dead Poets Society")."[25] The New York Times noted, "Mr. Hawke's subtle and strong performance makes it clear that Troy feels things too deeply to risk failure and admit he's feeling anything at all."[26] The following year Hawke received critical acclaim for his performance in Richard Linklater's 1995 drama Before Sunrise. The film follows a young American man (Hawke) and a young French woman (Julie Delpy), who meet on a train and disembark in Vienna, spending the night exploring the city and getting to know one another.[27] The San Francisco Chronicle praised Hawke's and Delpy's performances: "[they] interact so gently and simply that you feel certain that they helped write the dialogue. Each of them seems to have something personal at stake in their performances."[28]

Away from acting, Hawke directed the music video for the 1994 song "Stay (I Missed You)", by singer-songwriter Lisa Loeb, who was a member of Hawke's theater company at the time.[29] Spin magazine named Hawke and Loeb's video as its video of the year in 1994.[30] In a 2012 interview, Hawke said that the song, which was included in Reality Bites, is the only number-one popular song by an unsigned artist in the history of music.[31]

He published his first novel in 1996, The Hottest State, about a love affair between a young actor and a singer. Hawke said of the novel:

Writing the book had to do with dropping out of college, and with being an actor. I didn't want my whole life to go by and not do anything but recite lines. I wanted to try making something else. It was definitely the scariest thing I ever did. And it was just one of the best things I ever did.[14]

The book met with a mixed reception. Entertainment Weekly said that Hawke "opens himself to rough literary scrutiny in The Hottest State. If Hawke is serious ... he'd do well to work awhile in less exposed venues."[32] The New York Times thought Hawke did "a fine job of showing what it's like to be young and full of confusion", concluding that The Hottest State was ultimately "a sweet love story".[33]

In Andrew Niccol's science fiction film Gattaca (1997), "one of the more interesting scripts" Hawke said he had read in "a number of years",[34] he played the role of a man who infiltrates a society of genetically perfect humans by assuming another man's identity. Although Gattaca was not a success at the box office,[21] it drew generally favorable reviews from critics.[35] The Fort Worth Star-Telegram reviewer wrote that "Hawke, building on the sympathetic-but-edgy presence that has served him well since his kid-actor days, is most impressive".[36] In 1998, Hawke appeared alongside Gwyneth Paltrow and Robert De Niro in Great Expectations, a contemporary film adaptation of the Charles Dickens novel of the same name, directed by Alfonso Cuarón.[37] During the same year, Hawke collaborated with Linklater again on The Newton Boys, based on the true story of the Newton Gang.[38] Critical reviews for each film were mixed.[39][40] The following year, Hawke starred in Snow Falling on Cedars, based on David Guterson's novel of the same title.[41] Set in the Pacific Northwest and featuring a love affair between a European-American man and Japanese-American woman, the film met with an unenthusiastic reception;[42] Entertainment Weekly noted, "Hawke scrunches himself into such a dark knot that we have no idea who Ishmael is or why he acts as he does."[43]

2000s: Training Day, and Before Sunset

Hawke's next film role was in Michael Almereyda's 2000 film Hamlet, in which he played the title character. The film transposed the famous William Shakespeare play to contemporary New York City, a technique Hawke felt made the play more "accessible and vital".[44] Salon reviewer wrote: "Hawke certainly isn't the greatest Hamlet of living memory ... but his performance reinforces Hamlet's place as Shakespeare's greatest character. And in that sense, he more than holds his own in the long line of actors who've played the part."[45] In 2001, Hawke appeared in two more Linklater movies: Waking Life and Tape, both critically praised.[46][47] In the animated Waking Life, he shared a single scene with former co-star Delpy continuing conversations begun in Before Sunrise.[48] The real-time drama Tape, based on a play by Stephen Belber, takes place entirely in a single motel room with three characters played by Hawke, Robert Sean Leonard, and Uma Thurman.[49] Hawke regarded Tape as his "first adult performance",[50] a performance commended by Ebert for showing "both physical and verbal acting mastery".[51]

Hawke's next role, and one for which he received substantial critical acclaim, came in Training Day (2001). Hawke played rookie cop Jake Hoyt, alongside Denzel Washington, as one of a pair of narcotics detectives from the Los Angeles Police Department spending 24 hours in the gang neighborhoods of South Los Angeles. The film was a box office hit, taking $104 million worldwide, and garnered generally favorable reviews.[21][52] Variety wrote that "Hawke adds feisty and cunning flourishes to his role that allow him to respectably hold his own under formidable circumstances."[53] Paul Clinton of CNN reported that Hawke's performance was "totally believable as a doe-eyed rookie going toe-to-toe with a legend [Washington]".[54] Hawke himself described Training Day as his "best experience in Hollywood".[14] His performance earned him Screen Actors Guild and Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actor.[55][56]

Hawke pursued a number of projects away from acting throughout the early 2000s. He made his directorial debut with Chelsea Walls (2002), an independent drama about five struggling artists living in the famed Chelsea Hotel in New York City.[57] The film was critically and financially unsuccessful.[58] A second novel, 2002's Ash Wednesday, was better received and made the New York Times Best Seller list.[59] The tale of an AWOL soldier and his pregnant girlfriend,[14] the novel attracted critical praise. The Guardian called it "sharply and poignantly written ... makes for an intense one-sitting read".[60] The New York Times noted that in the book Hawke displayed "a novelist's innate gifts ... a sharp eye, a fluid storytelling voice and the imagination to create complicated individuals", but was "weaker at narrative tricks that can be taught".[61] In 2003, Hawke made a television appearance, guest starring in the second season of the television series Alias, where he portrayed a mysterious CIA agent.[62]

In 2004, Hawke returned to film, starring in two features, Taking Lives and Before Sunset. Upon release, Taking Lives received broadly negative reviews,[63] but Hawke's performance was favored by critics, with the Star Tribune noting that he "plays a complex character persuasively."[64] Before Sunset, the sequel to Before Sunrise (1995) co-written by Hawke, Linklater, and Delpy, was much more successful.[65] The Hartford Courant wrote that the three collaborators "keep Jesse and Celine iridescent and fresh, one of the most delightful and moving of all romantic movie couples."[66] Hawke called it one of his favorite movies, a "romance for realists".[67][68] Before Sunset was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, Hawke's first screenwriting Oscar nomination.[69]

Hawke starred in the 2005 action thriller Assault on Precinct 13, a loose remake of John Carpenter's 1976 film of the same title, with an updated plot. The film received ambivalent reviews; some critics praised the dark swift feel of the film, while others compared it unfavorably to John Carpenter's original.[70] Hawke also appeared that year in the political crime thriller Lord of War, playing an Interpol agent chasing an arms dealer played by Nicolas Cage.[71] In 2006, Hawke was cast in a supporting role in Fast Food Nation, directed by Richard Linklater based on Eric Schlosser's best-selling 2001 book.[72] The same year, Hawke directed his second feature, The Hottest State, based on his eponymous 1996 novel. The film was released in August 2007 to a tepid reception.[73]

In 2007, Hawke starred alongside Philip Seymour Hoffman, Marisa Tomei, and Albert Finney in the crime drama Before the Devil Knows You're Dead.[74] The final work of Sidney Lumet, the film received critical acclaim.[75] USA Today called it "highly entertaining", describing Hawke and Hoffman's performances as excellent.[76] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone praised Hawke's performance, noting that he "digs deep to create a haunting portrayal of loss".[77] The following year, Hawke starred with Mark Ruffalo in the crime drama What Doesn't Kill You. Despite the favorable reception,[78] the film was not given a proper theatrical release due to the bankruptcy of its distributor.[79] In 2009, Hawke appeared in two features: New York, I Love You, a romance movie comprising 12 short films,[80] and Staten Island, a crime drama co-starring Vincent D'Onofrio and Seymour Cassel.[81]

2010s: Before Midnight, Boyhood, First Reformed

In 2010, Hawke starred as a vampire hematologist in the science fiction horror film Daybreakers.[82] Filmed in Australia with the Spierig brothers, the feature received reasonable reviews,[83] and earned US$51 million worldwide.[21] His next role was in Antoine Fuqua's Brooklyn's Finest as a corrupt narcotics officer.[84] The film opened in March to a mediocre reception,[85] yet his performance was well received, with the New York Daily News concluding, "Hawke—continuing an evolution toward stronger, more intense acting than anyone might've predicted from him 20 years ago—drives the movie."[84] In the 2011 television adaptation of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, Hawke played the role of Starbuck, the first officer to William Hurt's Captain Ahab.[86] He then starred opposite Kristin Scott Thomas in Paweł Pawlikowski's The Woman in the Fifth, a "lush puzzler" about an American novelist struggling to rebuild his life in Paris.[87][88]

In 2012, Hawke entered the horror genre for the first time, by playing a true crime writer in Scott Derrickson's Sinister, which grossed US$87 million at the worldwide box office—the film was the first in a series of highly profitable films for Hawke after the start of the new decade.[89] In the week prior to the US opening of Sinister, Hawke explained that he was previously turned off by horror because good acting is not always required for success; however, the producer of Sinister, Jason Blum, who formerly ran a theater company with Hawke, made the offer to the actor based on the character and director.

when I was younger, I ran a theater company with this guy, Jason Blum. And he loved horror movies and he went on to create his own little subgenre with "Paranormal Activity". And he kept trying to talk to me about how I should love this whole genre. And I told him: I've never had a script with a really great character and a real filmmaker attached to it that I'd be interested in. So, he brought me into it.[31]

During 2013, Hawke starred in three films of different genres. Before Midnight, the third installment of the Before series, reunited Hawke with Delpy and Linklater.[90] Like its predecessors, the film garnered a considerable degree of critical acclaim;[91] Variety wrote that "one of the great movie romances of the modern era achieves its richest and fullest expression in Before Midnight," and called the scene in the hotel room "one for the actors' handbook."[92] The film earned co-writers Hawke, Linklater, and Delpy another Academy Award nomination, for Best Adapted Screenplay.[93]

Hawke then starred in the horror-thriller The Purge, about an American future where crime is legal for one night of the year. Despite mixed reviews,[94] the film topped the weekend box office with a US$34 million debut, the biggest opening of Hawke's career.[95] Hawke's third film of 2013 was the action thriller Getaway, which was both critically and commercially unsuccessful.[96][97]

The release of Linklater's Boyhood, a film shot over the course of 12 years, occurred in mid-2014.[98] It follows the life of an American boy from age 6 to 18, with Hawke playing the protagonist's father. The film became the best-reviewed film of 2014, and was named "Best Film" of the year by numerous critics associations.[99][100] Hawke said in an interview that the attention was a surprise to him. When he first became involved with Linklater's project, it did not feel like a "proper movie," and was like a "radical '60s film experiment or something".[101] At the following awards season, the film was nominated for Academy Award for Best Picture, while winning Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama and BAFTA Award for Best Film.[100] It also earned Hawke multiple awards nominations, including the Academy, BAFTA, Golden Globe, and SAG Award for Best Supporting Actor.[100]

Hawke next worked with the Spierig brothers again on the science fiction thriller Predestination, in which Hawke plays a time-traveling agent on his final assignment. Following its premiere at the 2014 SXSW Film Festival, the film was released in Australia in August 2014 and in the US in January 2015.[102] The film received largely positive reviews and was nominated for the AACTA Award for Best Film.[103][104] He then reunited with his Gattaca director Andrew Niccol for Good Kill. In this modern war film, Hawke played a drone pilot with a troubled conscience, which led to The Hollywood Reporter calling it his "best screen role in years."[105] Also in 2014, Hawke appeared in the movie Cymbeline which reunited him with his Assault on Precinct 13 co-star John Leguizamo.

In September 2014, Hawke's documentary debut, Seymour: An Introduction, screened at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), winning second runner-up for TIFF's People's Choice Award for Best Documentary.[106] Conceived after a dinner party at which both Hawke and Bernstein were present, the film is a profile of classical musician Seymour Bernstein, who explained that, even though he is typically a very private person, he was unable to decline Hawke's directorial request because he is "so endearing". Bernstein and Hawke developed a friendship through the filming process, and the classical pianist performed for one of Hawke's theater groups.[107] The film was released in March 2015 to a warm reception;[108] the Los Angeles Times reviewer described it as "quietly moving, indefinitely deep".[109]

Hawke had two films premiered at the 2015 TIFF, both garnering favorable reviews.[110][111] In Robert Budreau's drama film Born to Be Blue, he played the role of jazz musician Chet Baker.[112] The film is set in the late 1960s and focuses on the musician's turbulent career comeback plagued by heroin addiction.[113] His portrayal of Baker was well received; Rolling Stone noted that "Everything that makes Ethan Hawke an extraordinary actor — his energy, his empathy, his fearless, vanity-free eagerness to explore the deeper recesses of a character — is on view in Born to Be Blue."[114] In Rebecca Miller's romantic comedy Maggie's Plan, Hawke starred as an anthropologist and aspiring novelist alongside Greta Gerwig and Julianne Moore.[115] His other films that year included the coming-of-age drama Ten Thousand Saints and the psychological thriller Regression opposite Emma Watson. In November 2015, Hawke published his third novel, Rules for a Knight, in the form of a letter from a father to his four children about the moral values in life.[116]

In 2016, Hawke starred in Ti West's western film In a Valley of Violence, in which he played a drifter seeking revenge in a small town controlled by its Marshal (John Travolta).[117] He then portrayed two unpleasant characters in a row, first as the abusive father of a talented young baseball player in The Phenom, then as the harsh husband of Maud Lewis (played by Sally Hawkins) in Maudie. While some critics praised his unexpected turns,[118][119] others felt that Hawke was "miscast" as a cruel figure.[120] He reunited with Training Day director Antoine Fuqua and actor Denzel Washington for The Magnificent Seven (2016), a remake of the 1960 western film of the same name.[121] On June 7, his fourth book, Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars, a graphic novel he wrote with artist Greg Ruth, was released.[122]

In 2017, Hawke appeared in a cameo role in the science fiction film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets by Luc Besson;[123] and starred in Paul Schrader's drama film First Reformed, as a former military chaplain tortured by the loss of his son he encouraged to enlist in the armed forces, and focused on impending cataclysmic climate change. The film premiered at the 2017 Venice Film Festival to a positive reception.[124][125]

In 2018, Hawke had two films premiere at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.[126] In Juliet, Naked, a romantic comedy adapted from Nick Hornby's novel of the same name, he appeared as an obscure rock musician whose eponymous album set the plot in motion.[127] His third feature film, Blaze, based on the life of little-known country musician Blaze Foley, was selected in the festival's main competition section.[128] In addition, Hawke starred in Budreau's crime thriller Stockholm which premiered at the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival.[129] Hawke was in the 2019 western drama The Kid, directed by Vincent D'Onofrio.[130]

2020s: Continued work

In 2019, Hawke and Jason Blum adapted the book The Good Lord Bird into the miniseries based on the same name which premiered on October 4, 2020, on Showtime.[131][132][133][134]

He stars as abolitionist John Brown alongside Daveed Diggs, Ellar Coltrane, and includes an appearance of Maya Hawke. In the 2020 biographical film Tesla, he plays the title character, inventor and engineer Nikola Tesla.

His third novel, A Bright Ray of Darkness, was published in February 2021.[135] In 2022, Hawke starred as the primary villain Arthur Harrow in the Disney+ streaming series Moon Knight, produced by Marvel Studios,[136] and as serial killer of children The Grabber in the Blumhouse feature, The Black Phone. The latter marked Hawke's ninth collaboration with Blumhouse.[137] Also that year, he appeared in Robert Eggers' The Northman, a 10th-century Viking epic which was filmed in Ireland, alongside Nicole Kidman, Anya Taylor-Joy, and Willem Dafoe.[138][139]

In 2022, Hawke's six-part biographical documentary on Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, The Last Movie Stars, was broadcast on HBO Max.[140] Hawke also voiced Bruce Wayne/Batman in the animated children's television series Batwheels.[141]

Stage career

Hawke has described theater as his "first love",[142] a place where he is "free to be more creative".[143] Hawke made his Broadway debut in 1992, portraying the playwright Konstantin Treplev in Anton Chekhov's The Seagull at the Lyceum Theater in Manhattan.[144] The following year Hawke was a co-founder and the artistic director of Malaparte, a Manhattan theater company, which survived until 2000.[8][145] Outside the New York stage, Hawke made an appearance in a 1995 production of Sam Shepard's Buried Child, directed by Gary Sinise at the Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago.[146] In 1999, he starred as Kilroy in the Tennessee Williams play Camino Real at the Williamstown Theater Festival in Massachusetts.[147]

Hawke returned to Broadway in Jack O'Brien's 2003 production of Henry IV, playing Henry Percy (Hotspur).[148] New York magazine wrote: "Ethan Hawke's Hotspur ... is a compelling, ardent creation."[148] Ben Brantley of The New York Times reported that Hawke's interpretation of Hotspur might be "too contemporary for some tastes," but allowed "great fun to watch as he fumes and fulminates."[149] In 2005, Hawke starred in the Off-Broadway revival of David Rabe's dark comedy Hurlyburly.[150] The New York Times critic Brantley praised Hawke's performance as the central character Eddie, reporting that "he captures with merciless precision the sense of a sharp mind turning flaccid".[150] The performance earned Hawke a Lucille Lortel Award nomination for Outstanding Lead Actor.[151]

From November 2006 to May 2007, Hawke starred as Mikhail Bakunin in Tom Stoppard's trilogy play The Coast of Utopia, an eight-hour-long production at the Lincoln Center Theater in New York.[152] The Los Angeles Times complimented Hawke's take on Bakunin, writing: "Ethan Hawke buzzes in and out as Bakunin, a strangely appealing enthusiast on his way to becoming a famous anarchist."[153] The performance earned Hawke his first Tony Award nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Play.[154] In November 2007, he directed Things We Want, a two-act play by Jonathan Marc Sherman, for the artist-driven Off-Broadway company The New Group.[155] The play has four characters played by Paul Dano, Peter Dinklage, Josh Hamilton, and Zoe Kazan. New York magazine praised Hawke's "understated direction", particularly his ability to "steer a gifted cast away from the histrionics".[155]

The following year, Hawke received the Michael Mendelson Award for Outstanding Commitment to the Theater.[156] In his acceptance speech, Hawke said "I don't know why they're honoring me. I think the real reason they are honoring me is to help raise money for the theater company. Whenever the economy gets hit hard, one of the first thing [sic] to go is people's giving, and last on that list of things people give to is the arts because they feel it's not essential. I guess I'm here to remind people that the arts are essential to our mental health as a country."[156]

In 2009, Hawke appeared in two plays under British director Sam Mendes: as Trofimov in Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard and as Autolycus in Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale.[157] The two productions, launched in New York as part of the Bridge Project, went on an eight-month tour in six countries.[157] The Cherry Orchard won a mixed review from the New York Daily News, which wrote "Ethan Hawke ... fits the image of the 'mangy' student Trofimov, but one wishes he didn't speak with a perennial frog in his throat."[158] Hawke's performance in The Winter's Tale was better received,[159] earning him a Drama Desk Award nomination for Outstanding Featured Actor in a Play.[160]

In January 2010, Hawke directed his second play, A Lie of the Mind, by Sam Shepard on the New York stage.[161] It was the first major Off-Broadway revival of the play since its 1985 premiere.[162] Hawke said that he was drawn to the play's take on "the nature of reality",[163] and its "weird juxtaposition of humor and mysticism".[162] In his review for The New York Times, Ben Brantley noted the production's "scary, splendid clarity", and praised Hawke for eliciting a performance that "connoisseurs of precision acting will be savoring for years to come".[164] Entertainment Weekly commented that although A Lie of the Mind "wobbles a bit in its late stages", Hawke's "hearty" revival managed to "resurrect the spellbinding uneasiness of the original".[165] The production garnered five Lucille Lortel Award nominations including Outstanding Revival,[166] and earned Hawke a Drama Desk Award nomination for Outstanding Director of a Play.[167]

Hawke next starred in the Off-Broadway premiere of a new play, Tommy Nohilly's Blood from a Stone, from December 2010 to February 2011. The play was not a critical success,[168] but Hawke's portrayal of the central character Travis earned positive feedback; The New York Times said he was "remarkably good at communicating the buried sensitivity beneath Travis's veneer of wary resignation."[169] A contributor from the New York Post noted it was Hawke's "best performance in years".[170] Hawke won an Obie Award for his role in Blood from a Stone.[171] The following year Hawke played the title role in Chekhov's Ivanov at the Classic Stage Company.[172] In early 2013, he starred in and directed a new play Clive, inspired by Bertolt Brecht's Baal and written by Jonathan Marc Sherman.[173] Later that year, he played the title role in a Broadway production of Macbeth at the Lincoln Center Theater, but his performance failed to win over the critics, with the New York Post calling it "underwhelming" for showing untimely restraint in a flashy production.[174]

In 2019, Hawke returned to Broadway in the revival of Sam Shepard's True West, co-starring Paul Dano. The show was met with critical acclaim. It received the Critic's Pick from The New York Times.[175] The show's previews began on December 27, 2018, and officially opened January 24, 2019, closing on March 17, 2019.[176] Hawke is a member of the LAByrinth theatre company.

Personal life

Hawke lives in Boerum Hill, a Brooklyn neighborhood in New York City,[177] and owns a small island in Nova Scotia, Canada,[178] where he occasionally lives during the summer.[179] He is a second cousin twice-removed of Tennessee Williams on his father's side.[4][180] Hawke's maternal grandfather, Howard Lemuel Green, served five terms in the Texas Legislature (1957–67), served as the elected Tarrant County Judge in Texas from 1967 to 1975, and was also a minor-league baseball commissioner.[181][182] During his bachelor days, Hawke dated Kim Tannahill, a nanny who worked for Bruce Willis and Demi Moore.[183]

Family

On May 1, 1998, Hawke married actress Uma Thurman,[184] whom he had met on the set of Gattaca in 1996.[185] They have two children, Maya (b. 1998) and Levon (b. 2002).[186][187] The couple separated in 2003 amid allegations of Hawke's infidelity,[188] and filed for divorce the following year.[14] The divorce was finalized in August 2005.[189]

In 2008, Hawke married Ryan Shawhughes,[190][191] who had briefly worked as a nanny to his and Thurman's children before graduating from Columbia University.[191][192] Dismissing speculation about their relationship, Hawke said, "my [first] marriage disintegrated due to many pressures, none of which were remotely connected to Ryan."[192] They have two daughters, Clementine and Indiana.[193][194]

Beliefs

Hawke identifies as a feminist and has criticized "the movie business [being] such a boys' club."[195][196] He has also spoken in support of Colin Kaepernick and individual rights.[197]

Hawke is an Episcopalian. He joked on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert: "My mother always said we’re wannabe Catholics. We just didn’t want to do the hard work and we want to be able to get divorced."[198] Hawke directed Wildcat, a biopic about Flannery O'Connor, a devout Catholic, which starred his daughter, Maya.[199]

Philanthropy

Hawke has served as a co-chair of the New York Public Library's Young Lions Committee, one of New York's major philanthropic boards.[200] In 2001, Hawke co-founded the Young Lions Fiction Award, an annual prize for achievements in fiction by writers under 35.[201][202] In November 2010, he was honored as a Library Lion by the New York Public Library.[203] In May 2016, Hawke joined the library's board of trustees.[204]

Political views

Hawke supports the Democratic Party,[205] and supported Bill Bradley, John Kerry, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton for President of the United States in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2016, respectively.[206][207][208][209] He is also a supporter of gay rights; in March 2011, he and his wife released a video supporting same-sex marriage in New York.[210]

In an October 2012 interview, Hawke said that he prefers great art to politics, explaining that his preference shows "how little" he cares about the latter; "I think about the first people of our generation to do great art. I see Michael Chabon write a great book; when I see Philip Seymour Hoffman do Death of a Salesman last year—I see people of my generation being fully realized in their work, and I find that really kind of exciting. But politics? I don't know. Paul Ryan is certainly not my man."[31]

Hawke was critical of Donald Trump, criticizing him for his Make America Great Again slogan, and for threatening to put Hillary Clinton in jail.[211] According to Hawke, members of his family voted for Trump.[212]

Filmography

Discography

| Year | Song | Contribution | Artist | Album |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | "The Pink Seashell"[213] | Spoken Word | Fall Out Boy | So Much (for) Stardust |

Awards and nominations

Publications

- Hawke, Ethan (1996). The Hottest State: A Novel (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-54083-4. OCLC 34474927.

- Hawke, Ethan (2002). Ash Wednesday: A Novel (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41326-1. OCLC 48967928.

- Hawke, Ethan (April 2009). "The Last Outlaw Poet". Rolling Stone. No. 1076. pp. 50–61, 78–79. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009.

- Hawke, Ethan (2015). Rules for a Knight (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307962331.

- Hawke, Ethan (2016). Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars (1st ed.). New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-401-31099-8.

- Hawke, Ethan (2021). A Bright Ray of Darkness: A Novel (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-785-15260-3. OCLC 34474927.

References

- ^ "Ethan Hawke biography and filmography | Ethan Hawke movies". Tribute. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ Sprung, Shlomo (November 6, 2015). "November 6, birthdays for Ethan Hawke, Emma Stone, Sally Field". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Schindehette, Susan (June 17, 2002). "Mom on a Mission". People. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ a b Solomon, Deborah (September 16, 2007). "Renaissance Man?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Grossman, Anna Jane (January 20, 2012). "Vows: Leslie Hawke and David Weiss". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Ethan Hawke". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 8. Episode 12. April 21, 2002. Bravo.

- ^ a b c "Ethan Hawke Biography". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Hello Magazine Profile — Ethan Hawke". Hello!. Hello Ltd. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ Hurlburt, Roger (June 25, 1989). "Earning His Wings". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. p. 3F.

- ^ "The Ultimate New Jersey High School Yearbook — A-K". The Star-Ledger. June 7, 1998. p. 1.

- ^ a b Brockes, Emma (December 8, 2000). "Ethan Hawke: I never wanted to be a movie star". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Vadeboncoeur, Joan (January 22, 1995). "Despite Film Success, Hawke Keeps A Keen Eye On Theater". Syracuse Herald American. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, Dana (April 14, 2002). "The Payoff for Ethan Hawke". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Halpern, Dan (October 8, 2005). "Another sunrise". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (July 12, 1985). "The Screen: 'Explorers'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Explorer Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. July 12, 1985. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society Review". Variety. January 1, 1989. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. June 2, 1989. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "1990 in Film". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Ethan Hawke Movie Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Mahar, Ted (January 24, 1991). "'White Fang': A Boy, A Mine And A Dog". The Oregonian. p. C14.

- ^ "A Midnight Clear – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. March 9, 2010. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 15, 1993). "Alive Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 18, 1994). "Reality Bites". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ James, Caryn (February 18, 1994). "Coming of Age in Snippets: Life as a Twentysomething". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (January 27, 1995). "An Extraordinary Day Dawns 'Before Sunrise'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Shulgasser, Barbara (January 27, 1995). "Modern "Roman Holiday' alive and well in Vienna". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "The best Ethan Hawke scene". The Guardian. London. December 19, 2000. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Levy, Joe (December 1994). "A dress for success: Lisa Loeb, 'Stay'". Video of the Year. Spin magazine. Vol. 10, no. 9. p. 90. ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Mike (October 9, 2014). "Ethan Hawke, 'Sinister' Star, On The Disappointment Of Post-'Reality Bites' Generation X". HuffPost. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (October 18, 1996). "The Hottest State — Book Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Nessel, Jen (November 3, 1996). "Love Hurts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ Chanko, Kenneth M. (October 26, 1997). "Hawke-ing the future in science-fiction thriller 'Gattaca'". U-T San Diego. p. E-6.

- ^ "Gattaca (1997): Reviews". Metacritic. October 24, 1997. Archived from the original on November 28, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Price, Michael H. (October 24, 1997). "Gattaca Well-conceived sci-fi". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. p. 38.

- ^ Tatara, Paul (February 6, 1998). "Review: What the Dickens is 'Great Expectations'?". CNN. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ Stack, Peter (March 27, 1998). "Bank-Robbing 'Newton' Brothers Show Boys Will Be Boys". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "The Newton Boys". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Great Expectations". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (January 7, 2000). "Review: 'Snow Falling on Cedars' a visual feast". CNN. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Snow Falling on Cedars". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (January 7, 2000). "Snow Falling on Cedars — Movie Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Dominguez, Robert (May 11, 2000). "A Renaissance Man tackles Shakespeare 'Hamlet's' Ethan Hawke has more on his mind than movie stardom". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (May 12, 2000). "Hamlet". Salon. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Waking Life Reviews". Metacritic. October 19, 2001. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "Tape Reviews". Metacritic. November 2, 2001. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 12, 2001). "Surreal Adventures Somewhere Near the Land of Nod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Denby, David (November 12, 2001). "Tape". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ Hendricks, Brian (July 2009). "Ethan Hawke". Hobo Magazine. No. 11. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 16, 2001). "Tape". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ "Training Day (2001): Reviews". Metacritic. October 5, 2001. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (August 31, 2001). "Training Day Review". Variety. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (October 4, 2001). "Review: 'Training Day' a course worth taking". CNN. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "SAG awards nominations in full". BBC News. January 29, 2002. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Brook, Tom (March 21, 2002). "Ethan Hawke's Oscar surprise". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Diones, Bruce (May 6, 2002). "The Film File: Chelsea Walls". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Chelsea Walls Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Best Sellers; Hardcover Fiction". The New York Times Book Review. August 11, 2002. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Falconer, Helen (October 19, 2002). "American ego trip". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ James, Caryn (August 16, 2002). "Books of the Times; So He's Famous. Give Him a Break, if Not a Free Ride". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (November 26, 2002). "Hawke Eye". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ "Taking Lives (2004): Reviews". Metacritic. March 19, 2004. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Covert, Colin (March 19, 2004). "'Lives' digs its own grave". Star Tribune. p. 12E.

- ^ "Before Sunset Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (July 1, 2004). "Movie review: 'Before Sunset'". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ Adler, Shawn (July 5, 2007). "Ethan Hawke Laments Lost 'Before Sunset' Threequel". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Lee (July 19, 2004). "Love that goes with the flow". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (January 25, 2005). "'Aviator' leads Oscar nominations". CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2005): Reviews". Metacritic. January 19, 2005. Archived from the original on September 20, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Jacobs, Andy (October 13, 2005). "Lord of War". BBC. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Hall, Sandra (October 25, 2006). "Fast Food Nation". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "The Hottest State Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ McCarthy, Ellen (November 2, 2007). "Ethan Hawke's Deal With the 'Devil'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (November 1, 2007). "'Before the Devil Knows You're Dead' is darkly real". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (October 18, 2007). "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 12, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ "What Doesn't Kill You (2008): Reviews". Metacritic. December 12, 2008. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (December 12, 2008). "Bob Yari crashes into Chapter 11". Variety. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "LaBeouf, Bloom, Christie in 'Love You". Entertainment Weekly. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ Webster, Andy (November 20, 2009). "Movie Reviews – Staten Island". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Moore, Roger (January 4, 2010). "Ethan Hawke dons fangs for Daybreakers". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ "Daybreakers (2010): Reviews". Metacritic. January 8, 2010. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Neumaier, Joe (March 5, 2010). "Brooklyn's Finest' star Ethan Hawke perfectly conveys constant threat of job with New York police". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Brooklyn's Finest (2010): Reviews". Metacritic. March 9, 2010. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Moby Dick Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Preston, John (June 10, 2010). "Ethan Hawke Interview". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ DeFore, John (September 13, 2011). "The Woman in the Fifth: Toronto Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "Sinister". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "'Before Midnight,' Love Darkens And Deepens". NPR. May 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Before Midnight Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Chang, Justin (January 21, 2013). "Review: 'Before Midnight'". Variety. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (January 16, 2014). "Oscars: 9 Films Nominated for Best Picture". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 23, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "The Purge". Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (June 10, 2013). "Ethan Hawke talks about his surprise No. 1 movie, 'The Purge'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "Getaway". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "Getaway (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ McNary, Dave (March 27, 2014). "Richard Linklater's 'Boyhood' Set for Summer Release". Variety. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ "The Best and Worst Movies of 2014". Metacritic. January 6, 2015. Archived from the original on March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Best of 2014: Film Awards & Nominations Scorecard". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Hughes, Jason (December 3, 2014). "Ethan Hawke Didn't Expect 'Boyhood' to Win Awards or Be Critically Acclaimed (Video)". The Wrap. The Wrap News Inc. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (March 7, 2014). "SXSW: 11 must-see movies on the menu in Texas". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ "Predestination (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Rahman, Abid (December 3, 2014). "'Predestination,' 'Water Diviner' Lead Australian Film Awards Nominations". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Rooney, David (September 5, 2014). "'Good Kill': Venice Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Nigel M (September 14, 2014). "'The Imitation Game' Wins the People's Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival". Indiewire. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Ho, Solarina (September 12, 2014). "Ethan Hawke 'Seymour' documentary is intimate portrait of pianist". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Seymour: An Introduction (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. March 13, 2015. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Sharkey, Betsy (March 19, 2015). "'Seymour' is Ethan Hawke's moving look at pianist Bernstein". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Born To Be Blue (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. March 25, 2016. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ "Maggie's Plan (2016)". Rotten Tomatoes. May 20, 2016. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Queenan, Joe (July 20, 2016). "Born to Be Blue: Ethan Hawke on the fast life and mysterious death of Chet Baker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (November 29, 2014). "Ethan Hawke: 'Mining your life is the only way to stumble on anything real'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Travers, Peter (March 24, 2016). "Born to Be Blue". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (May 26, 2016). "'Maggie's Plan': As smart and funny as vintage Woody Allen". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Lach, Eric (November 9, 2015). "Ethan Hawke Explains His Thing for Knights". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ "In a Valley of Violence Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Nigel M (April 18, 2016). "The Phenom review: baseball movie throws a curveball". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (June 22, 2017). "'Maudie': Sally Hawkins delights as a hard-luck pauper who loves life". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (June 15, 2017). "'Maudie' Review: Sally Hawkins Saves an Otherwise Missed Opportunity". TheWrap. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Hertz, Barry (September 6, 2016). "How Ethan Hawke survived Hollywood". The Globe and Mail. Canada. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke's Indeh is a Graphic Novel History of Two Peoples". June 6, 2016. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham (July 9, 2017). "Luc Besson, Utopian Spaceman". New York. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ "First Reformed (2017)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ McNary, Dave (September 15, 2017). "Ethan Hawke-Amanda Seyfried Thriller 'First Reformed' Bought by A24 for U.S." Variety. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (November 29, 2017). "Sundance Film Festival Unveils Full 2018 Features Lineup". Variety. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (January 19, 2018). "Sundance Film Review: 'Juliet, Naked'". Variety. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Fleishman, Jeffrey (June 8, 2017). "Ethan Hawke lets us in his editing room and reveals what Philip Seymour Hoffman taught him". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Nolfi, Joey (March 7, 2018). "Tribeca Film Festival lineup features Sarah Jessica Parker drama, Liz Garbus NYT doc series". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (September 20, 2017). "Vincent D'Onofrio Sets Jake Schur In Title Role Of 'The Kid'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Lang, Brent (June 11, 2018). "Ethan Hawke, Jason Blum Adapting 'The Good Lord Bird' for TV". Variety. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "Academy Award(R) Nominee Ethan Hawke to Executive Produce and Star in Showtime(R) Limited Series "Good Lord Bird"". The Futon Critic. March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Showtime Taps Tony Winner Daveed Diggs and Wyatt Russell in "The Good Lord Bird"". The Futon Critic. August 2, 2019.

- ^ Rico, Klaritza (May 13, 2020). "TV News Roundup: Showtime Sets 'The Good Lord Bird' Premiere Date (Watch)". Variety. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "A Bright Ray of Darkness by Ethan Hawke". Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke to Play Villain Opposite Oscar Isaac in Marvel's 'Moon Knight' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. January 15, 2021. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (January 28, 2021). "Ethan Hawke Boards Blumhouse Scott Derrickson Feature 'The Black Phone'". Deadline. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke stars as King Aurvandil in director Robert Eggers' Viking epic The Northman". Focus Features. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "Robert Eggers' 'Northman' Terrifies Kidman, Taylor-Joy Says You've Never Seen Anything Like It". IndieWire. November 5, 2020. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Olsen, Mark (July 22, 2022). "Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward were movie stars for 50 years. A new doc explains how". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "WarnerMedia Announces 'Batwheels' Cast". Animation World Network. September 12, 2021. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ Kirschling, Gregory (August 24, 2007). "Spotlight on Ethan Hawke". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Villarreal, Yvonne (January 7, 2010). "Ethan Hawke is always in development". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Rich, Frank (November 30, 1992). "Review/Theater: The Seagull; A Vain Little World Of Art and Artists, Painted by Chekhov". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Landman, Beth; Spiegelman, Ian (May 15, 2000). "Babies Lower Boom on Theater Group". New York. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ^ "Buried Child (September 20, 1995 – November 5, 1995)". Steppenwolf Theater Company Official Website. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (June 28, 1999). "Theater Review; Lost Souls, Not So Different From Their Creator". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Simon, John (November 24, 2003). "Star Turns". New York. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (November 21, 2003). "Theater Review; Falstaff and Hal, With War Afoot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Brantley, Ben (April 21, 2005). "Sloppy Losers With Fried Brains Hunt for Clarity". The New York Times.

- ^ "2005 Nominations and Recipients". Lucille Lortel Awards Official Website. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ McCarter, Jeremy (May 28, 2007). "Arise, Ye Prisoners of Tom Stoppard". New York. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Winer, Linda (December 22, 2006). "The Coast of Utopia, Part Two: Shipwreck". Newsday (via Los Angeles Times). Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Glitz, Michael (August 19, 2007). "'State' of mind". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ a b McCarter, Jeremy (November 16, 2007). "We've Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway". New York. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Aleksander, Irina (November 11, 2008). "At Fête for Ethan Hawke, Actors Justin Long and Billy Crudup Recall What It's Like to Be Laid Off". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Hodson, Heather (May 8, 2009). "Sam Mendes and Kevin Spacey: The Bridge Project". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Dziemianowicz, Joe (January 16, 2009). "'Cherry Orchard' blossoms at BAM". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ Dziemianowicz, Joe (February 23, 2009). "'The Winter's Tale,' 'Othello' are suspicious but delicious". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "As usual, non-Broadway shows get stomped at the Drama Desk Awards". Los Angeles Times. May 17, 2009. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ Sternbergh, Adam (January 31, 2010). "The Ethan Hawke Actors Studio". New York. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Healy, Patrick (January 27, 2010). "New Search for the Truth in 'A Lie'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Jacobson, Murrey (February 24, 2010). "Conversation: Ethan Hawke on Directing Shepard's 'A Lie of the Mind'". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (February 19, 2010). "Home Is Where the Soul Aches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (February 18, 2010). "Stage Review — A Lie of the Mind (2010)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (April 1, 2010). "Lucille Lortel Nominees Announced". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (May 3, 2010). "Drama Desk fetes 'Ragtime,' 'Scottsboro'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (January 13, 2011). "The women of 'Blood from a Stone'". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (January 12, 2011). "Discord Dished Up at Every Meal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (January 12, 2011). "Heavy 'Stone' sinks". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (May 16, 2011). "'Chad Deity' Takes Obie For Best New American Play". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Cox, Gordon (May 31, 2012). "Hawke, Sheik set for CSC". Variety. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (May 22, 2012). "Ethan Hawke Will Star in and Direct New Play for New Group". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (November 22, 2013). "Ethan Hawke underwhelming in 'Macbeth'". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (January 24, 2019). "Review: Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano Go Mano a Mano in the Riveting 'True West'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "True West Paul Dano and Ethan Hawke star in Sam Shepard's Pulitzer-nominated drama". Broadway. 2018. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Dailey, Jessica (April 5, 2013). "Ethan Hawke Leaves Chelsea For $3.9M Boerum Hill Townhouse". Curbed. Archived from the original on August 30, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Dobbins, Amanda (June 5, 2013). "Ethan Hawke Explains Island Shopping, Tang". New York. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Doucette, Keith (October 26, 2015). "Ethan Hawke special guest at native water ceremony in Nova Scotia". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Carr, David (January 10, 2013). "In His Comfort Zone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ^ Colloff, Pamela. "Where I'm from: Ethan Hawke". Texas Monthly. No. December 2005. pp. 112–114. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ Simnacher, Joe (October 15, 2005). "Howard Lemuel Green — Baseball, history, politics defined the actor's grandfather". The Dallas Morning News. p. 17B.

- ^ "Kim Louise Tannahill Archived August 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine". The Lewiston Tribune. February 11, 2018.

- ^ Cheng, Kipp; Chang, Suna (May 15, 1998). "Monitor". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Rohrer, Trish Deitch (June 2000). "The Great Dane". Los Angeles Magazine. Vol. 45, no. 6. p. 80. Bibcode:1989Natur.338...27C. doi:10.1038/338027b0. ISSN 1522-9149. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- ^ "Obituaries". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. October 14, 2005. pp. B5 Metro. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

Howard Green, 84, passed away Thursday, Oct. 13, 2005.... Survivors: Wife, Mary Utley Green; daughter, Leslie Green Hawke of Bucharest, Romania; grandson, Ethan Green Hawke and his offspring: Maya Thurman Hawke and Levon Green Hawke, of New York, N.Y....

- ^ Eells, Josh (March 24, 2016). "Ethan Hawke on Biopics, Chet Baker, and Breaking Out". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Halle and hubby separate; Uma 'holding up' after Ethan split; Will Smith parties in London". San Francisco Chronicle. October 2, 2003. Archived from the original on October 13, 2003. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (October 7, 2005). "Uma Calls Split from Ethan 'Excruciating'". People. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Vozick-Levinson, Simon (July 18, 2008). "Monitor". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Garratt, Sheryl (October 8, 2012). "Ethan Hawke interview". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Barton, Laura (May 16, 2009). "Desperately seeking Ethan". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke and wife welcome daughter Clementine". USA Today. Associated Press. July 23, 2008. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "Report: It's A Girl For Ethan Hawke". Access Hollywood. August 6, 2011. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke: 25 Things You Don't Know About Me". Us Weekly. July 13, 2014. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Maas, Jeniffer (May 13, 2015). "Ethan Hawke speaks out on the 'boys club' in Hollywood". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke – What's In My Bag?". Amoeba Records. December 3, 2018. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Lea, Jessica (July 22, 2022). "Ethan Hawke Says This 'Great Christian Thinker' Could Help Pope Stop War in Ukraine". Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Mastromatteo, Mike (August 7, 2024). "Ethan and Maya Hawke hope 'Wildcat' will attract truth-seekers". Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Aleksander, Irina (April 1, 2008). "Who's Who in Charity: New York's Most Powerful Philanthropic Boards". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

- ^ "Young Lions Fiction Award". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gaffney, Adrienne (March 17, 2009). "Disproving the Notion That Kids These Days Only Write in Tweets". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "2010 Library Lions Malcolm Gladwell, Ethan Hawke, Paul LeClerc, Steve Martin, and Zadie Smith Fêted on Monday, November 1" (Press release). New York Public Library. August 4, 2010. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "The New York Public Library Adds Ethan Hawke To Its Board of Trustees" (Press release). New York Public Library. May 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Kresse, Jim (September 28, 2001). "Tragedy also makes for strange bedfellows". The Spokesman-Review. p. D2.

- ^ Leonard, Devin (September 26, 1999). "Can Dollar Bill Bradley Dunk Al Gore?". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Pulumbarit, Oliver M. (October 23, 2004). "Super Exclusive Interview". Philippine Daily Inquirer. p. 1.

- ^ Blas, Lorena (November 5, 2008). "Celebrities, including an unexpected one, celebrate Obama's win". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Evans-Harding, Natalie (December 16, 2017). "Ethan Hawke: 'The most romantic thing I've done is have sex'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ "Ethan and Ryan Hawke for HRC's New Yorkers for Marriage Equality". Human Rights Campaign Official Website. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Hensch, Mark (October 24, 2016). "Actor Ethan Hawke slams Trump's 'fascist behavior'". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ White, Abbey (October 2, 2020). "Ethan Hawke Says Family Members Who Voted for Trump Disappointed With His Administration". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ Bowenbank, Starr (March 3, 2023). "Fall Out Boy Unveils 'So Much (For) Stardust' Tracklist, Featuring Ethan Hawke Collab". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

External links

- Ethan Hawke at IMDb

- Ethan Hawke at the Internet Broadway Database

- Ethan Hawke at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Ethan Hawke at Rotten Tomatoes

- Ethan Hawke at The Filmaholic

- Ethan Hawke Interview on Texas Monthly Talks (November 2007)

- 1970 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- Activists from New York (state)

- American male child actors

- American male film actors

- American male novelists

- American male screenwriters

- American male Shakespearean actors

- American male stage actors

- American male voice actors

- American theatre directors

- Best Supporting Actor Genie and Canadian Screen Award winners

- Carnegie Mellon University College of Fine Arts alumni

- Daytime Emmy Award winners

- Film directors from New Jersey

- Film directors from New York City

- Film directors from Texas

- Hun School of Princeton alumni

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Male Lead winners

- Male actors from Austin, Texas

- Male actors from New Jersey

- Male actors from New York City

- American male feminists

- American feminists

- New York (state) Democrats

- New York University alumni

- Novelists from New Jersey

- Novelists from Texas

- Obie Award recipients

- People from West Windsor, New Jersey

- Screenwriters from New York (state)

- Screenwriters from Texas

- Texas Democrats

- West Windsor-Plainsboro High School South alumni

- Writers from Austin, Texas

- Writers from Manhattan

- Actors from Mercer County, New Jersey