Estradiol undecylate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪɒl ənˈdɛsɪleɪt/ ES-trə-DY-ol un-DESS-il-ayt |

| Trade names | Delestrec, Progynon Depot 100, others |

| Other names | EU; E2U; Estradiol undecanoate; Estradiol unducelate; RS-1047; SQ-9993 |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular injection[1] |

| Drug class | Estrogen; Estrogen ester |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | IM injection: High |

| Protein binding | Estradiol: ~98% (to albumin and SHBG)[2][3] |

| Metabolism | Cleavage via esterases in the liver, blood, and tissues[4][5] |

| Metabolites | Estradiol, undecanoic acid, estradiol metabolites[4][5] |

| Elimination half-life | Unknown |

| Duration of action | IM injection: • 10–12.5 mg: 1–2 months[6][7] • 25–50 mg: 2–4 months[8] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.020.616 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H44O3 |

| Molar mass | 440.668 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Estradiol undecylate (EU, EUn, E2U), also known as estradiol undecanoate and formerly sold under the brand names Delestrec and Progynon Depot 100 among others, is an estrogen medication which has been used in the treatment of prostate cancer in men.[9][10][11][12][1] It has also been used as a part of hormone therapy for transgender women.[13][14][15] Although estradiol undecylate has been used in the past, it was discontinued.[11][16][failed verification] The medication has been given by injection into muscle usually once a month.[1][17][12]

Side effects of estradiol undecylate in men may include breast tenderness, breast development, feminization, sexual dysfunction, infertility, fluid retention, and cardiovascular issues.[17] Estradiol undecylate is an estrogen and hence is an agonist of the estrogen receptor, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[5][4] It is an estrogen ester and a very long-lasting prodrug of estradiol in the body.[4][5] Because of this, it is considered to be a natural and bioidentical form of estrogen.[4][18][19] An injection of estradiol undecylate has a duration of about 1 to 4 months.[7][8][6][20]

Estradiol undecylate was first described in 1953 and was introduced for medical use by 1956.[7][21][8][22] It remained in use as late as the 2000s before being discontinued.[23][11][24] Estradiol undecylate was marketed in Europe, but does not seem to have ever been available in the United States.[14][25][11] It was used for many years as a parenteral estrogen to treat prostate cancer in men, although it was not employed as often as polyestradiol phosphate.[12]

Medical uses

[edit]Estradiol undecylate has been used as a form of high-dose estrogen therapy to treat prostate cancer, but has since largely been superseded for this indication by newer agents with fewer adverse effects (e.g., gynecomastia and cardiovascular complications) like GnRH analogues and nonsteroidal antiandrogens.[1][26] It has been assessed for this purpose in a number of clinical studies.[27][28][29][30][31] It has been used at a dosage of 100 mg every 3 to 4 weeks (or once a month) by intramuscular injection for this indication.[17][32]

Estradiol undecylate has been used to suppress sex drive in sex offenders.[33] It has been used for this indication at a dosage of 50 to 100 mg by intramuscular injection once every 3 to 4 weeks.[33]

Estradiol undecylate has also been used to treat breast cancer in women.[34] It has been used in menopausal hormone therapy as well, for instance in the treatment of hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms.[8] Along with estradiol valerate, estradiol cypionate, and estradiol benzoate, estradiol undecylate has been used as an intramuscular estrogen in feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women.[13][14][15] It has been used at doses of 100 to as much as 800 mg per month by intramuscular injection for this purpose.[14][15][13][35][36][37]

| Route/form | Estrogen | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Estradiol | 1–2 mg 3x/day | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.25–2.5 mg 3x/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol | 0.15–3 mg/day | ||

| Ethinylestradiol sulfonate | 1–2 mg 1x/week | ||

| Diethylstilbestrol | 1–3 mg/day | ||

| Dienestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Hexestrol | 5 mg/day | ||

| Fosfestrol | 100–480 mg 1–3x/day | ||

| Chlorotrianisene | 12–48 mg/day | ||

| Quadrosilan | 900 mg/day | ||

| Estramustine phosphate | 140–1400 mg/day | ||

| Transdermal patch | Estradiol | 2–6x 100 μg/day Scrotal: 1x 100 μg/day | |

| IM or SC injection | Estradiol benzoate | 1.66 mg 3x/week | |

| Estradiol dipropionate | 5 mg 1x/week | ||

| Estradiol valerate | 10–40 mg 1x/1–2 weeks | ||

| Estradiol undecylate | 100 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Polyestradiol phosphate | Alone: 160–320 mg 1x/4 weeks With oral EE: 40–80 mg 1x/4 weeks | ||

| Estrone | 2–4 mg 2–3x/week | ||

| IV injection | Fosfestrol | 300–1200 mg 1–7x/week | |

| Estramustine phosphate | 240–450 mg/day | ||

| Note: Dosages are not necessarily equivalent. Sources: See template. | |||

Available forms

[edit]Estradiol undecylate was available as an oil solution for intramuscular injection provided in ampoules at a concentration of 100 mg/mL.[23][38]

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications of estrogens include coagulation problems, cardiovascular diseases, liver disease, and certain hormone-sensitive cancers such as breast cancer and endometrial cancer, among others.[39][40][41][42]

Side effects

[edit]Estradiol undecylate and its side effects have been evaluated for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer in a phase III international multicenter randomized controlled trial headed by Jacobi and colleagues of the Department of Urology, University of Mainz.[17][43][44][45][46][28][47] The study consisted of 191 patients from 12 treatment centers, who were treated for 6 months with intramuscular injections of either 100 mg/month estradiol undecylate (96 men) or 300 mg/week cyproterone acetate (95 men).[43][45][46][28][47][48][49] Findings for a subgroup of 42 men at the University of Mainz center were initially reported in 1978 and 1980.[50][17][28][47] These men were age 51 to 84 years (mean 68 years), and men with pre-existing cardiovascular disease were excluded.[12][17][51] A considerable incidence of cardiovascular complications was reported for the estradiol undecylate group (76%; 16/21 incidence total); there was a 67% (14/21) incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and a 9.5% (2/21) incidence of cardiovascular mortality.[12][17][51] The cardiovascular morbidity in this group included peripheral edema and superficial thrombophlebitis (38%; 8/21), coronary heart disease (24%; 5/21), and a deep vein thrombosis (4.8%; 1/21), while the cardiovascular mortality included a myocardial infarction (4.8%; 1/21) and a pulmonary embolism (4.8%; 1/21).[17][51] Eight of the cases of cardiovascular complications in the estradiol undecylate group, including the two deaths, were regarded as "severe".[51][52] Conversely, no incidence of cardiovascular toxicity occurred in the cyproterone acetate comparison group (0%; 0/21).[12][17][51] Other side effects of estradiol undecylate included gynecomastia (100%; 21/21) and erectile dysfunction (90%; 19/21).[17] The cardiovascular complications with estradiol undecylate in this relatively small study are in contrast to large and high-quality clinical studies of high-dose polyestradiol phosphate and transdermal estradiol for prostate cancer, in which minimal to no cardiovascular toxicity has been observed.[53][54][55][56][57]

An expanded report of 191 patients, which included the 42 patients from the University of Mainz center plus an additional 149 patients from 11 other centers, was published in 1982.[43][49] The antitumor effectiveness of estradiol undecylate and cyproterone acetate in this study was equivalent.[43][45][58][46][28][47] The rates of improvement, no response, and deterioration were 52%, 41%, and 7% in the estradiol undecylate group and 48%, 44%, and 8% in the cyproterone acetate group, respectively.[43][46] However, the incidence of a selection of specific side effects, including gynecomastia, breast tenderness, and edema, was significantly lower in the cyproterone acetate group than in the estradiol undecylate group (37% vs. 94%, respectively).[43][45][46][59] Gynecomastia specifically occurred in 13% (12/96) of the patients in the cyproterone acetate group and 77% (73/95) of the patients in the estradiol undecylate group.[43][45] Erectile dysfunction occurred in "essentially all" patients in both groups.[49] Leg edema occurred in 18% (17/95) of the estradiol undecylate group and 4.2% (4/96) of the cyproterone acetate group, while the incidences of superficial thrombophlebitis and coronary heart disease both were not described.[43] The incidence of thrombosis was 4.2% (4/95) in the estradiol undecylate group and 5.3% (5/96) in the cyproterone acetate group.[43][48][49] There were five deaths in total, three in the estradiol undecylate group and two in the cyproterone acetate group.[43] Two of the deaths in each of the treatment groups were due to cardiovascular events, while the remaining death in the estradiol undecylate group was due to unknown causes.[43][46][49] The similar rate of cardiovascular complications besides edema between estradiol undecylate and cyproterone acetate that was observed is in contrast to the initial 42-patient report and to findings with other estrogens, such as diethylstilbestrol and estramustine phosphate, which have been shown to possess significantly higher cardiovascular toxicity than cyproterone acetate.[45] On the basis of the expanded study, the researchers concluded that cyproterone acetate was an "acceptable alternative" to estrogen therapy with estradiol undecylate, but with a "considerably more favorable" side-effect profile.[46]

After the completion of the initial expanded study, a 5-year extension trial primarily of the Ruhr University Bochum center subgroup, led by Tunn and colleagues, was conducted.[29][44][45][28][48][47] In this study, the cyproterone acetate group was changed from intramuscular injections to 100 mg/day oral cyproterone acetate.[29][45] Of the 39 patients in the study, the global 5-year survival rate was not significantly different between the estradiol undecylate and cyproterone acetate groups (24% and 26%, respectively).[29][45][28][48][47] In patients without metastases, the 5-year survival rate was 51% in the cyproterone acetate group relative to 43% in the estradiol undecylate group, although the difference was not statistically significant.[29][45] In terms of non-prostate cancer deaths, there were 5 in the CPA group and 6 in the EU group.[29] The incidence of cardiovascular-related mortality was 3 deaths in the CPA group and 3 deaths in the EU group.[29]

| Side effect | Estradiol undecylate 100 mg/month i.m. (n = 96) |

Cyproterone acetate 100 mg/day oral (n = 95) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gynecomastia* | 74 | 77.1% | 12 | 12.6% |

| Breast tenderness* | 84 | 87.5% | 6 | 6.3% |

| Sexual impotence | "Occurred in essentially all patients of both groups"

| |||

| Leg edema* | 17 | 17.7% | 4 | 4.2% |

| Thrombosis | 4 | 4.2% | 5 | 5.3% |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 2 | 2.1% | 2 | 2.1% |

| Other mortality | 1a | 1.0% | 0 | 0% |

| Notes: For 6 months in 191 men age 51 to 88 years with prostate cancer. Footnotes: * = Differences in incidences between groups were statistically significant. a = Due to unknown causes. Sources: See template. | ||||

The side effects of estradiol undecylate have also been studied and reported beyond the preceding clinical trial programme and for other patient populations, for instance women. Side effects during therapy with massive doses of estradiol undecylate (200 mg three times per week, or 600 mg per week and around 2,400 mg per month total) in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer have included appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, nipple pigmentation, breast pain, rash, urinary incontinence, edema, drowsiness, hypercalcemia, and local injection-site reactions.[34] Like with other estrogens, treatment with estradiol undecylate has been found to produce testicular abnormalities and disturbances of spermatogenesis in men.[60] In transgender women, estradiol undecylate by intramuscular injection at extremely high doses (200–800 mg/month) was associated with greater incidence of hyperprolactinemia (high prolactin levels) than ethinylestradiol orally at a dose of 100 μg/day (or about 3 mg/month total) (rates of 40% and 16% for prolactin levels greater than 1,000 mU/L, respectively).[35] Switching from estradiol undecylate to ethinylestradiol resulted in a decrease in prolactin levels in many individuals.[35] The preceding dosage of estradiol undecylate corresponds to much greater estrogenic exposure than the dosage of ethinylestradiol.[35] Cyproterone acetate was also used in combination with estrogen in the study.[35]

Overdose

[edit]Estradiol undecylate has been used clinically at massive doses of as much as 800 to 2,400 mg per month by intramuscular injection, given in divided doses of 100 to 200 mg per injection two to three times per week.[34][15][35][36][37] For purposes of comparison, a single 100 mg intramuscular injection of estradiol undecylate has been reported to produce estradiol levels of about 500 pg/mL.[61] Symptoms of estrogen overdosage may include nausea, vomiting, bloating, increased weight, water retention, breast tenderness, vaginal discharge, heavy legs, and leg cramps.[39] These side effects can be diminished by reducing the estrogen dosage.[39]

Interactions

[edit]Inhibitors and inducers of cytochrome P450 may influence the metabolism of estradiol and by extension circulating estradiol levels.[62]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Esters of estradiol like estradiol undecylate are readily hydrolyzed prodrugs of estradiol, but have an extended duration when administered in oil via intramuscular injection due to a depot effect afforded by their fatty acid ester moiety.[5] As prodrugs of estradiol, estradiol undecylate and other estradiol esters are estrogens.[4][5] Estradiol undecylate is of about 62% higher molecular weight than estradiol due to the presence of its C17β undecylate ester.[9][11] Because estradiol undecylate is a prodrug of estradiol, it is considered to be a natural and bioidentical form of estrogen.[4][18][19]

The effects of estradiol undecylate on cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, testosterone, prolactin, and sex hormone-binding globulin levels as well as on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis have been studied in men with prostate cancer and compared with those of high-dose cyproterone acetate therapy.[63][64][65][66][67][17][68][69][70][71] The effects of estradiol undecylate on serum lipids and ceruloplasmin levels have been studied as well.[72][73][74] Additionally, the influence of estradiol undecylate on SHBG levels and free testosterone fraction in women has been described.[75]

| Estrogen | Form | Dose (mg) | Duration by dose (mg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPD | CICD | ||||

| Estradiol | Aq. soln. | ? | – | <1 d | |

| Oil soln. | 40–60 | – | 1–2 ≈ 1–2 d | ||

| Aq. susp. | ? | 3.5 | 0.5–2 ≈ 2–7 d; 3.5 ≈ >5 d | ||

| Microsph. | ? | – | 1 ≈ 30 d | ||

| Estradiol benzoate | Oil soln. | 25–35 | – | 1.66 ≈ 2–3 d; 5 ≈ 3–6 d | |

| Aq. susp. | 20 | – | 10 ≈ 16–21 d | ||

| Emulsion | ? | – | 10 ≈ 14–21 d | ||

| Estradiol dipropionate | Oil soln. | 25–30 | – | 5 ≈ 5–8 d | |

| Estradiol valerate | Oil soln. | 20–30 | 5 | 5 ≈ 7–8 d; 10 ≈ 10–14 d; 40 ≈ 14–21 d; 100 ≈ 21–28 d | |

| Estradiol benz. butyrate | Oil soln. | ? | 10 | 10 ≈ 21 d | |

| Estradiol cypionate | Oil soln. | 20–30 | – | 5 ≈ 11–14 d | |

| Aq. susp. | ? | 5 | 5 ≈ 14–24 d | ||

| Estradiol enanthate | Oil soln. | ? | 5–10 | 10 ≈ 20–30 d | |

| Estradiol dienanthate | Oil soln. | ? | – | 7.5 ≈ >40 d | |

| Estradiol undecylate | Oil soln. | ? | – | 10–20 ≈ 40–60 d; 25–50 ≈ 60–120 d | |

| Polyestradiol phosphate | Aq. soln. | 40–60 | – | 40 ≈ 30 d; 80 ≈ 60 d; 160 ≈ 120 d | |

| Estrone | Oil soln. | ? | – | 1–2 ≈ 2–3 d | |

| Aq. susp. | ? | – | 0.1–2 ≈ 2–7 d | ||

| Estriol | Oil soln. | ? | – | 1–2 ≈ 1–4 d | |

| Polyestriol phosphate | Aq. soln. | ? | – | 50 ≈ 30 d; 80 ≈ 60 d | |

Notes and sources

Notes: All aqueous suspensions are of microcrystalline particle size. Estradiol production during the menstrual cycle is 30–640 µg/d (6.4–8.6 mg total per month or cycle). The vaginal epithelium maturation dosage of estradiol benzoate or estradiol valerate has been reported as 5 to 7 mg/week. An effective ovulation-inhibiting dose of estradiol undecylate is 20–30 mg/month. Sources: See template. | |||||

Antigonadotropic activity

[edit]

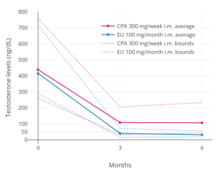

A phase III clinical trial comparing high-dose intramuscular cyproterone acetate (300 mg/week) and high-dose intramuscular estradiol undecylate (100 mg/month) in the treatment of prostate cancer found that estradiol undecylate suppressed testosterone levels into the castrate range (< 50 ng/dL)[76] within at least 3 months whereas testosterone levels with cyproterone acetate were significantly higher and above the castrate range even after 6 months of treatment.[17] With estradiol undecylate, testosterone levels fell from 416 ng/dL to 38 ng/mL (–91%) after 3 months and to 29.6 ng/dL (–93%) after 6 months, whereas with cyproterone acetate, testosterone levels fell from 434 ng/dL to 107 ng/mL (–75%) at 3 months and to 102 ng/mL (–76%) at 6 months.[17] In another study using the same dosages, estradiol undecylate suppressed testosterone levels by 97% while CPA suppressed them by 70%.[67] In accordance, whereas estrogens are well-established as able to suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range at sufficiently high dosages,[77] progestogens like cyproterone acetate on their own are able to decrease testosterone levels only up to an apparent maximum of around 70 to 80%.[78][79] Besides effects on testosterone levels, the long-term effects of estradiol undecylate on testicular morphology in transgender women have been studied.[60]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The pharmacokinetics of estradiol undecylate have been assessed limitedly in a few studies.[80][81][82][83][65][84][7][8] Following a single intramuscular injection of 100 mg estradiol undecylate in oil, mean levels of estradiol were about 500 pg/mL a day after injection and about 340 pg/mL 14 days after injection in 4 people.[80] Levels of estradiol with intramuscular estradiol undecylate were reported to be very irregular and to vary by as much as 10-fold between individuals.[80] In another study, following a single intramuscular injection of 32.2 mg estradiol undecylate, levels of estradiol peaked at around 400 pg/mL after 3 days and decreased from this peak to around 200 pg/mL after 6 days in 3 postmenopausal women.[81][85] In a repeated administration study of 100 mg per month estradiol undecylate in 14 men with prostate cancer, estradiol levels at trough were about 560 pg/mL at 3 months and about 540 pg/mL at 6 months following initiation of therapy.[65] In a larger follow-up of the study with 21 men, estradiol levels at trough were about 36 pg/mL at baseline, 486 pg/mL at 3 months, and 598 pg/mL at 6 months of therapy.[70] In one further study, levels of estradiol in an unspecified number of postmenopausal women following a single injection of 100 mg estradiol undecylate were said to be between 300 pg/mL and 600 pg/mL six days post-injection.[75]

Due to its more protracted duration, doses of estradiol undecylate that are typical of other estradiol esters produce only "subthreshold" estradiol levels, and for this reason, higher single doses of estradiol undecylate are necessary for similar effects.[86][80][81] However, the relatively low levels of estradiol produced by lower doses of estradiol undecylate are favorable for menopausal replacement therapy.[86]

The duration of estradiol undecylate is markedly prolonged relative to that of estradiol benzoate, estradiol valerate, and many other estradiol esters.[61][6][20][18] A single intramuscular injection of 10 to 12.5 mg estradiol undecylate has a duration of 40 to 60 days (~1–2 months) and of 25 to 50 mg estradiol undecylate has an estimated duration of effect of 2 to 4 months in postmenopausal women.[7][8][6][20] A single intramuscular injection of 20 to 30 mg estradiol undecylate has been found to inhibit ovulation when used as an estrogen-only injectable contraceptive in premenopausal women for 1 to 3 months (mean 1.7 months) as well.[87] When used at a higher dose of 100 mg per injection in men with prostate cancer, estradiol undecylate has been given usually once a month.[17][32] After a single subcutaneous injection of estradiol undecylate in rats, its duration of effect was 80 days (about 2.5 months).[88][89][90] Due to its very prolonged duration, estradiol undecylate has been described in general as a favorable alternative to estradiol implants.[8]

The excretion of estradiol undecylate has been studied as well.[83]

Estradiol undecylate has not been used via oral administration. However, a closely related estradiol ester, estradiol decanoate (estradiol decylate), has been studied via the oral route, and has been found to possess significant oral bioavailability, to produce relatively high estradiol levels of about 100 pg/mL after a single 0.5 mg oral dose and about 100 to 150 pg/mL with continuous 0.25 mg/day oral therapy, and to have a much higher estradiol-to-estrone ratio than oral estradiol of about 2:1.[91][92][93] It is thought that this is due to absorption of estradiol decanoate by the lymphatic system and a consequent partial bypass of first-pass metabolism in the liver and intestines,[91][92][93] which is similarly known to occur with oral testosterone undecanoate.[94][95]

-

Estradiol levels after a single intramuscular injection of 10 mg estradiol valerate in oil or 100 mg estradiol undecylate in oil both in 4 individuals each.[61] Subject characteristics and assay method were not described.[61] Source was Vermeulen (1975).[61]

-

Estradiol levels after a short intravenous infusion of 20 mg estradiol in aqueous solution or an intramuscular injection of equimolar doses of estradiol esters in oil solution in 3 postmenopausal women each.[82][96] Assays were performed using radioimmunoassay with chromatographic separation.[82][96] Sources were Geppert (1975) and Leyendecker et al. (1975).[82][96]

-

Estradiol, testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels with an intramuscular injection of 32.3 mg estradiol undecylate in oil in 3 postmenopausal women.[82][96] Assays were performed using radioimmunoassay with chromatographic separation.[96][82] Sources were Geppert (1975) and Leyendecker et al. (1975).[82][96]

-

Estradiol, testosterone, and prolactin levels with 100 mg/month estradiol undecylate in oil by intramuscular injection in 14 to 28 men with prostate cancer.[65] A follow-up of the study with more men and with additional hormones was also subsequently published.[70] Sources were Jacobi & Altwein (1979) and Derra (1981).[65][70]

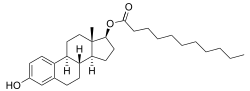

Chemistry

[edit]Estradiol undecylate is a synthetic estrane steroid and an estradiol ester.[9][10] It is specifically the C17β undecylate (undecanoate) ester of estradiol.[9][10][11] The compound is also known as estradiol 17β-undecylate or as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol 17β-undecanoate.[10][11] The undecylic acid (undecanoic acid) ester of estradiol undecylate is a medium-chain fatty acid and is found naturally in many foods, some examples of which include coconut, fruits, fats, oils, and rice.[97]

Estradiol undecylate is a relatively long-chain ester of estradiol.[10][11] Its undecylate ester contains 11 carbon atoms.[10][11] For comparison, the ester chains of estradiol acetate, estradiol valerate, and estradiol enantate have 2, 5, and 7 carbon atoms, respectively.[10][11] As a result of its longer ester chain, estradiol undecylate is the most lipophilic of these estradiol esters, and for this reason, has by far the longest duration when administered in oil solution by intramuscular injection.[61][98][99] An example of an estradiol ester with a longer ester chain than estradiol undecylate is estradiol stearate (Depofollan), which has 18 carbon atoms and has been used in medicine as an estrogen as well.

A few estradiol esters related to estradiol undecylate include estradiol decanoate, estradiol diundecylate, and estradiol diundecylenate.[9][10] Estradiol undecylate shares the same undecylate ester as testosterone undecanoate, an androgen/anabolic steroid and very long-lasting testosterone ester.[9][10]

Estradiol undecylate is one of the longest-chain steroid esters that has been in common medical use.[100]

| Estrogen | Structure | Ester(s) | Relative mol. weight |

Relative E2 contentb |

log Pc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position(s) | Moiet(ies) | Type | Lengtha | ||||||

| Estradiol | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.0 | ||

| Estradiol acetate | C3 | Ethanoic acid | Straight-chain fatty acid | 2 | 1.15 | 0.87 | 4.2 | ||

| Estradiol benzoate | C3 | Benzoic acid | Aromatic fatty acid | – (~4–5) | 1.38 | 0.72 | 4.7 | ||

| Estradiol dipropionate | C3, C17β | Propanoic acid (×2) | Straight-chain fatty acid | 3 (×2) | 1.41 | 0.71 | 4.9 | ||

| Estradiol valerate | C17β | Pentanoic acid | Straight-chain fatty acid | 5 | 1.31 | 0.76 | 5.6–6.3 | ||

| Estradiol benzoate butyrate | C3, C17β | Benzoic acid, butyric acid | Mixed fatty acid | – (~6, 2) | 1.64 | 0.61 | 6.3 | ||

| Estradiol cypionate | C17β | Cyclopentylpropanoic acid | Cyclic fatty acid | – (~6) | 1.46 | 0.69 | 6.9 | ||

| Estradiol enanthate | C17β | Heptanoic acid | Straight-chain fatty acid | 7 | 1.41 | 0.71 | 6.7–7.3 | ||

| Estradiol dienanthate | C3, C17β | Heptanoic acid (×2) | Straight-chain fatty acid | 7 (×2) | 1.82 | 0.55 | 8.1–10.4 | ||

| Estradiol undecylate | C17β | Undecanoic acid | Straight-chain fatty acid | 11 | 1.62 | 0.62 | 9.2–9.8 | ||

| Estradiol stearate | C17β | Octadecanoic acid | Straight-chain fatty acid | 18 | 1.98 | 0.51 | 12.2–12.4 | ||

| Estradiol distearate | C3, C17β | Octadecanoic acid (×2) | Straight-chain fatty acid | 18 (×2) | 2.96 | 0.34 | 20.2 | ||

| Estradiol sulfate | C3 | Sulfuric acid | Water-soluble conjugate | – | 1.29 | 0.77 | 0.3–3.8 | ||

| Estradiol glucuronide | C17β | Glucuronic acid | Water-soluble conjugate | – | 1.65 | 0.61 | 2.1–2.7 | ||

| Estramustine phosphated | C3, C17β | Normustine, phosphoric acid | Water-soluble conjugate | – | 1.91 | 0.52 | 2.9–5.0 | ||

| Polyestradiol phosphatee | C3–C17β | Phosphoric acid | Water-soluble conjugate | – | 1.23f | 0.81f | 2.9g | ||

| Footnotes: a = Length of ester in carbon atoms for straight-chain fatty acids or approximate length of ester in carbon atoms for aromatic or cyclic fatty acids. b = Relative estradiol content by weight (i.e., relative estrogenic exposure). c = Experimental or predicted octanol/water partition coefficient (i.e., lipophilicity/hydrophobicity). Retrieved from PubChem, ChemSpider, and DrugBank. d = Also known as estradiol normustine phosphate. e = Polymer of estradiol phosphate (~13 repeat units). f = Relative molecular weight or estradiol content per repeat unit. g = log P of repeat unit (i.e., estradiol phosphate). Sources: See individual articles. | |||||||||

History

[edit]Estradiol undecylate was first described in the scientific literature, along with estradiol valerate and a variety of other estradiol esters, by Karl Junkmann of Schering AG in 1953.[101][7] It was introduced for medical use via intramuscular injection by 1956.[21][8][22] Syntex applied for a patent for estradiol undecylate in 1958, which was granted in 1961 and was given a priority date of 1957.[23][102] Estradiol undecylate was introduced for medical use and was employed for decades, but was eventually discontinued.[11][25][38] It remained in use in some countries as late as the 2000s.[23][11][24]

Harry Benjamin reported on the use of estradiol undecylate in transgender women in his book The Transsexual Phenomenon in 1966 and in a literature review in the Journal of Sex Research in 1967.[14][103]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Estradiol undecylate is the generic name of the drug and its INN and USAN.[9][10][11][16] It is also spelled in some publications as estradiol unducelate and is also known as estradiol undecanoate.[61][9][10][11][16] In German, it is known under a variety of spellings including as estradiolundecylat, östradiolundecylat, östradiolundezylat, oestradiolundecylat, oestradiolundezylat, and others.[104] Estradiol undecylate is known by its former developmental code names RS-1047 and SQ-9993 as well.[9][10][11][16]

Brand names

[edit]The major brand name of estradiol undecylate is Progynon Depot 100.[9][10][11] It has also been marketed under other brand names including Delestrec, Depogin, Estrolent, Oestradiol D, Oestradiol-Retard Theramex, and Primogyn Depot [0,1 mg/ml], among others.[9][10][11][23][24]

Availability

[edit]Estradiol undecylate was available in the Europe (including in France, Germany, Great Britain, Monaco, the Netherlands, Switzerland), and Japan.[11][23][105][22][106] However, it has been discontinued and hence is no longer available.[25][38]

Research

[edit]Estradiol undecylate was studied by Schering alone as an estrogen-only injectable contraceptive in premenopausal women at a dose of 20 to 30 mg once a month.[85][87][107][108] It was effective, lacked breast and thromboembolic complications, lacked other side effects besides amenorrhea, and prevented ovulation for 1 to 3 months (mean 1.7 months) following a single dose.[87] However, uterine growth of 1 to 2 cm was observed after one year, and endometrial hyperplasia was occasionally encountered.[85][87][107] The preparation was not further developed as a form of birth control due to the risks of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer associated with long-term unopposed estrogen therapy.[87]

Estradiol undecylate, in combination with norethisterone enanthate (at doses of 5 to 10 mg and 50 to 70 mg, respectively), was studied by Schering as a combined injectable contraceptive in premenopausal women and was found to be effective and well-tolerated, but ultimately was not marketed for this use.[109][108][87][110][111][112]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Zink C (1 January 1988). Dictionary of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Walter de Gruyter. p. 85. ISBN 978-3-11-085727-6.

- ^ Stanczyk FZ, Archer DF, Bhavnani BR (June 2013). "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception. 87 (6): 706–727. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. PMID 23375353.

- ^ Falcone T, Hurd WW (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 22, 362, 388. ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Oettel M, Schillinger E (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 261,544. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

Natural estrogens considered here include: [...] Esters of 17β-estradiol, such as estradiol valerate, estradiol benzoate and estradiol cypionate. Esterification aims at either better absorption after oral administration or a sustained release from the depot after intramuscular administration. During absorption, the esters are cleaved by endogenous esterases and the pharmacologically active 17β-estradiol is released; therefore, the esters are considered as natural estrogens.

- ^ a b c d e f Kuhl H (August 2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 (Suppl 1): 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ a b c d Labhart A (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 551–553. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Wied GL (January 1954). "[Estradiol valerate and estradiol undecylate, two new estrogens with prolonged action; comparison with estradiol benzoate]" [Estradiol valerate and estradiol undecylate, two new estrogens with prolonged action; comparison with estradiol benzoate]. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde (in German). 14 (1): 45–52. PMID 13142295.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gouygou C, Gueritee N, Pye A (1956). "[A fat-soluble, delayed estrogen : the estradiol undecylate]" [A fat-soluble, delayed estrogen: the estradiol undecylate]. Therapie (in French). 11 (5): 909–917. PMID 13391788.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 898–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Roberts AD (1991). Dictionary of Steroids: Chemical Data, Structures, and Bibliographies. CRC Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-412-27060-4. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis US. 2000. p. 405. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Norman G, Dean ME, Langley RE, Hodges ZC, Ritchie G, Parmar MK, et al. (February 2008). "Parenteral oestrogen in the treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review". British Journal of Cancer. 98 (4): 697–707. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604230. PMC 2259178. PMID 18268497.

- ^ a b c Schlatterer K, von Werder K, Stalla GK (1996). "Multistep treatment concept of transsexual patients". Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 104 (6): 413–419. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211479. PMID 9021341. S2CID 25099676.

- ^ a b c d e Benjamin H, Lal GB, Green R, Masters RE (1966). The Transsexual Phenomenon. Ace Publishing Company. p. 107.

Another preparation of even higher potency is Squibb's Delestrec, which at this writing is not yet on the market in the United States, but is well known in Germany and other European countries under the name of Progynon Depot (Schering). It is chemically Estradiol Undecylate in oil, likewise slowly absorbing, and containing 100 mg. to 1 cc. Injections of 1 cc. once or twice a month can be sufficient. Occasionally, however, larger doses are required to influence the patient's emotional distress.

- ^ a b c d Israel GE (March 2001). Transgender Care: Recommended Guidelines, Practical Information, and Personal Accounts. Temple University Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-1-56639-852-7.

- ^ a b c d "Estradiol".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Jacobi GH, Altwein JE, Kurth KH, Basting R, Hohenfellner R (June 1980). "Treatment of advanced prostatic cancer with parenteral cyproterone acetate: a phase III randomised trial". British Journal of Urology. 52 (3): 208–215. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1980.tb02961.x. PMID 7000222.

- ^ a b c International Society of Urology (1973). Reports of the Congress. Livingstone. p. 252.

Progynon-Depot ist eine Oestrogenpräparat mit einem Depoteffekt von 4-6 Wochen. 1 ml Progynon Depot 100 mg enthält 100 mg Oestra- diolundecylat in öliger Lösung. Oestradiolundecylat ist ein Ester des natürlichen Oestrogens Oestradiol.

- ^ a b Lembeck F, Sewing KF (7 March 2013). Pharmakologie-Fibel: Tafeln zur Pharmakologie-Vorlesung. Springer-Verlag. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-3-642-65621-7.

- ^ a b c Wilde PR, Coombs CF, Short AJ (1959). The Medical Annual: A Year Book of Treatment and Practitioner's Index ... Publishing Science Group.

As in the case of progestogens the esters of oestradiol vary in the duration of their effect. Oestradiol benzoate is short-acting (three days to a week). Oestradiol valerianate is somewhat longer-acting, and oestradiol enanthate and undecylate have considerably more prolonged duration of effectiveness. The undecylate may remain effective for some months, and should not be employed, [...]

- ^ a b Halkerston ID, Hillman J, Palmer D, Rundle A (July 1956). "Changes in the excretion pattern of neutral 17-ketosteroids during oestrogen administration to male subjects". The Journal of Endocrinology. 13 (4): 433–438. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0130433. PMID 13345960.

- ^ a b c Bishop PM (1958). "Endocrine Treatment of Gynaecological Disorders". In Gardiner-Hill H (ed.). Modern Trends in Endocrinology. Vol. 1. London: Butterworth & Co. pp. 231–244.

- ^ a b c d e f Kleemann A, Engel J, Kutscher B, Reichert D (2009). Pharmaceutical Substances: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs (5th ed.). Thieme. pp. 1167–1174. ISBN 978-3-13-179525-0.

- ^ a b c Index Nominum: International Drug Directory. CRC Press. 2004. pp. 469–. ISBN 978-3-88763-101-7.

- ^ a b c "Micromedex".

- ^ Mutschler E, Derendorf H (1995). Drug Actions: Basic Principles and Therapeutic Aspects. CRC Press. p. 609. ISBN 978-0-8493-7774-7. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Enfedjieff M (March 1974). "[Experiences with hormonal treatment of prostatic carcinoma]" [Experiences with hormonal treatment of prostatic carcinoma]. Zeitschrift für Urologie und Nephrologie (in German). 67 (3): 171–173. PMID 4848715. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23.

Treatment of prostatic carcinoma in 256 patients using parenteral injections of Progynon Depot (a depto estradiol preparation) is reported. 58% of patients survived 3 or more years from beginning of treatment, and in 70% therapeutic results were considered good with regression of tumor mass, reduction or disappearance of pain, normalization of miction, and improved general status. Results of estrogen treatment are evident within 3 months in most cases. Side effects include gynecomastia in 95% of cases, impotence in almost all patients, and atrophic changes in the testicles, which may actually be desirable. Prostatectomy is not recommended because of the high incidence of metastases even when prostatic disease is still small, because of the high operative mortality, and because of the undesirable after-effects. Orchidectomy was performed in patients in whom the prostatic capsule had been invaded, or who had distant metastases. Estrogen therapy for prostatic carcinoma gives excellent results, and is very easy for both patient and physician.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tunn UW (1987). "Antiandrogene in der Therapie des fortgeschrittenen Prostatakarzinoms" [Antiandrogens in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer]. Konservative Therapie des Prostatakarzinoms [Conservative Therapy of Prostate Cancer] (in German). pp. 113–121. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-72613-2_12. ISBN 978-3-540-17724-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saborowski KJ (1988), Konservative Therapie mit Cyproteronacetat und Estradiolundecylat beim Fortgeschrittenen Prostatacarcinom: Eine 5-Jahres-Studie [Conservative Therapy with Cyproterone Acetate and Estradiol Undecylate in Advanced Prostate Cancer: A 5-Year Study] (in German), Bochum, Univ., Diss., OCLC 917571781, OL 24895092W

- ^ Mollard P (March 1963). "[Clinical action of estradiol undecylate in the treatment of prostatic cancer]" [Clinical action of estradiol undecylate in the treatment of prostatic cancer]. Lyon Medical (in French). 209: 759–765. PMID 13935867.

- ^ Schubert GE, Ziegler H, Völter D (1973). "[Comparison of histological and cytological studies of the prostate with special reference to oestrogene induced changes (author's transl)]" [Comparison of histological and cytological studies of the prostate with special reference to oestrogene induced changes]. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pathologie (in German). 57: 315–318. PMID 4142204. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^ a b Satoskar RS, Bhandarkar SD, Rege NN (1973). Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. Popular Prakashan. pp. 934–. ISBN 978-81-7991-527-1.

- ^ a b Morgan HG, Morgan MH (1984). Aids to Psychiatry. Churchill Livingstone. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-443-02613-3.

Treatment of sexual offenders. Hormone therapy. [...] Oestrogens may cause breast hypertrophy, testicular atrophy, osteoporosis (oral ethinyl oestradiol 0.01-0.05 mg/day causes least nausea). Depot preparation: oestradiol [undecyleate] 50-100mg once every 3–4 weeks. Benperidol or butyrophenone and the antiandrogen cyproterone acetate also used.

- ^ a b c Kennedy BJ (April 1967). "Effect of massive doses of estradiol undecylate in advanced breast cancer". Cancer Chemother Rep. 51 (2): 491–495.

- ^ a b c d e f Asscheman H, Gooren LJ, Assies J, Smits JP, de Slegte R (June 1988). "Prolactin levels and pituitary enlargement in hormone-treated male-to-female transsexuals". Clinical Endocrinology. 28 (6): 583–588. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb03849.x. PMID 2978262. S2CID 29214187.

- ^ a b Asscheman H, Gooren LJ, Eklund PL (September 1989). "Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender hormone treatment". Metabolism. 38 (9): 869–873. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(89)90233-3. PMID 2528051.

- ^ a b Gazzeri R, Galarza M, Gazzeri G (December 2007). "Growth of a meningioma in a transsexual patient after estrogen-progestin therapy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (23): 2411–2412. doi:10.1056/NEJMc071938. PMID 18057351.

- ^ a b c Sweetman SC, ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2098. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b c Lauritzen C (September 1990). "Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 199–214. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90004-P. PMID 2215269.

- ^ Lauritzen C, Studd JW (22 June 2005). Current Management of the Menopause. CRC Press. pp. 95–98, 488. ISBN 978-0-203-48612-2.

- ^ Laurtizen C (2001). "Hormone Substitution Before, During and After Menopause" (PDF). In Fisch FH (ed.). Menopause – Andropause: Hormone Replacement Therapy Through the Ages. Krause & Pachernegg: Gablitz. pp. 67–88. ISBN 978-3-901299-34-6.

- ^ Midwinter A (1976). "Contraindications to estrogen therapy and management of the menopausal syndrome in these cases". In Campbell S (ed.). The Management of the Menopause & Post-Menopausal Years: The Proceedings of the International Symposium held in London 24–26 November 1975 Arranged by the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of London. MTP Press Limited. pp. 377–382. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-6165-7_33. ISBN 978-94-011-6167-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jacobi GH (June 1982). "Intramuscular cyproterone acetate treatment for advanced prostatic carcinoma: results of the first multicentric randomized trial". In Schröder FH (ed.). Proceedings Androgens and Anti-androgens, International Symposium, Utrecht, June 5th, 1982. Schering Nederland BV. pp. 161–169. ISBN 978-9090004327. OCLC 11786945.

- ^ a b Tunn UW, Graff J, Senge T (June 1982). "Treatment of inoperable prostatic cancer with cyproterone acetate". In Schröder FH (ed.). Proceedings Androgens and Anti-androgens, International Symposium, Utrecht, June 5th, 1982. Schering Nederland BV. pp. 149–159. ISBN 978-9090004327. OCLC 11786945.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Tunn UW, Radlmaier A, Neumann F (1988). "Antiandrogens in Cancer Treatment". In Stoll BA (ed.). Endocrine Management of Cancer: Contemporary Therapy. pp. 43–56. doi:10.1159/000415355. ISBN 978-3-8055-4686-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schröder FH, Radlmaier A (2009). "Steroidal Antiandrogens". In Jordan VC, Furr BJ (eds.). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Humana Press. pp. 325–346. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_15. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Ackermann R, Altwein JE, Faul P (13 March 2013). Aktuelle Therapie des Prostatakarzinoms. Springer-Verlag. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-3-642-84264-1.

- ^ a b c d Namer M (October 1988). "Clinical applications of antiandrogens". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 31 (4B): 719–729. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90023-4. PMID 2462132.

- ^ a b c d e Jacobi GR, Tunn UW, Senge TH (1 December 1982). "Clinical experience with cyproterone acetate for palliation of inoperable prostate cancer". In Jacobi GH, Hohenfellner R (eds.). Prostate Cancer. Williams & Wilkins. pp. 305–319. ISBN 978-0-683-04354-9.

- ^ Altwein JE, Jacobi GH, Hohenfellner R (1978). "Estrogen versus cyproterone acetate in untreated inoperable carcinoma of the prostate: first results of an open, prospective, randomized study". Abstracts 3rd Congress of the European Association of Urology, Monte Carlo.

- ^ a b c d e Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, et al. (1983). "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation. 10 (1): 40–48. doi:10.1007/BF00326861. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015. S2CID 23447326.

- ^ Jacobi GH, Wenderoth UK (1982). "Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues for prostate cancer: untoward side effects of high-dose regimens acquire a therapeutical dimension". European Urology. 8 (3): 129–134. doi:10.1159/000473499. PMID 6281023.

- ^ Ockrim J, Lalani EN, Abel P (October 2006). "Therapy Insight: parenteral estrogen treatment for prostate cancer--a new dawn for an old therapy". Nature Clinical Practice. Oncology. 3 (10): 552–563. doi:10.1038/ncponc0602. PMID 17019433. S2CID 6847203.

- ^ Lycette JL, Bland LB, Garzotto M, Beer TM (December 2006). "Parenteral estrogens for prostate cancer: can a new route of administration overcome old toxicities?". Clinical Genitourinary Cancer. 5 (3): 198–205. doi:10.3816/CGC.2006.n.037. PMID 17239273.

- ^ Russell N, Cheung A, Grossmann M (August 2017). "Estradiol for the mitigation of adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy". Endocrine-Related Cancer. 24 (8): R297 – R313. doi:10.1530/ERC-17-0153. PMID 28667081.

- ^ Langley RE, Cafferty FH, Alhasso AA, Rosen SD, Sundaram SK, Freeman SC, et al. (April 2013). "Cardiovascular outcomes in patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer treated with luteinising-hormone-releasing-hormone agonists or transdermal oestrogen: the randomised, phase 2 MRC PATCH trial (PR09)". The Lancet. Oncology. 14 (4): 306–316. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70025-1. PMC 3620898. PMID 23465742.

- ^ Langley RE, Gilbert DC, Duong T, Clarke NW, Nankivell M, Rosen SD, et al. (February 2021). "Transdermal oestradiol for androgen suppression in prostate cancer: long-term cardiovascular outcomes from the randomised Prostate Adenocarcinoma Transcutaneous Hormone (PATCH) trial programme" (PDF). Lancet. 397 (10274): 581–591. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00100-8. PMC 7614681. PMID 33581820. S2CID 231885186.

- ^ Tunn UW, Senge T, Jacobi GH (1983). "Erfahrungen mit Cyproteronacetat als Monotherapie beim Inoperablen Prostatakarzinom" [Experience with Cyproterone Acetate as Monotherapy for Inoperable Prostate Cancer]. In Klosterhalfen H (ed.). Therapie des Fortgeschrittenen Prostatakarzinoms. Vortragsveranstaltung für Urologen, Berlin 1982/83 [Therapy of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Lecture Event for Urologists, Berlin 1982/83]. Wiss Buchreihe, Schering AG. pp. 67–76. ISBN 978-3921817162. OCLC 67592679.

- ^ Schröder FH (1996). "Cyproterone Acetate — Results of Clinical Trials and Indications for Use in Human Prostate Cancer". Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer. ESO Monographs. pp. 45–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45745-6_4. ISBN 978-3-642-45747-0.

- ^ a b Schulze C (January 1988). "Response of the human testis to long-term estrogen treatment: morphology of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells and spermatogonial stem cells". Cell and Tissue Research. 251 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1007/BF00215444. PMID 3342442. S2CID 22847105.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vermeulen A (1975). "Longacting steroid preparations". Acta Clinica Belgica. 30 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/17843286.1975.11716973. PMID 1231448.

- ^ Cheng ZN, Shu Y, Liu ZQ, Wang LS, Ou-Yang DS, Zhou HH (February 2001). "Role of cytochrome P450 in estradiol metabolism in vitro". Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 22 (2): 148–154. PMID 11741520.

- ^ Schürmeyer T, Graff J, Senge T, Nieschlag E (March 1986). "Effect of oestrogen or cyproterone acetate treatment on adrenocortical function in prostate carcinoma patients". Acta Endocrinologica. 111 (3): 360–367. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1110360. PMID 2421511.

- ^ Spona J, Lunglmayr G (July 1980). "Prolaktin-Serumspiegel unter Behandlung des Prostatakarzinoms mit Östradiol-17 beta-undezylat und Cyproteronazetat". Verhandlungsbericht der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Urologie [Serum Prolactin Levels During Therapy of Prostatic Cancer with Estradiol-17 beta-undecylate and Cyproterone Acetate] (in German). Vol. 92. pp. 494–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81706-9_120. ISBN 978-3-540-11017-0. PMID 6933738.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Jacobi GH, Altwein JE (1979). "Bromocriptin als Palliativtherapie beim fortgeschrittenen Prostatakarzinom:Experimentelles und klinisches Profil eines Medikamentes" [Bromocriptine as Palliative Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer: Experimental and Clinical Profile of a Drug]. Urologia Internationalis. 34 (4): 266–290. doi:10.1159/000280272. PMID 89747.

- ^ Schulze H, Senge T (1987). "Klassische Methoden des Androgenentzugs in der Therapie des fortgeschrittenen Prostatakarzinoms". Konservative Therapie des Prostatakarzinoms. pp. 89–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-72613-2_8. ISBN 978-3-540-17724-1.

- ^ a b Neumann F, El Etreby MF, Habenicht U, Radlmaier A, Bormacher K (1987). "Möglichkeiten des Androgenentzugs und der totalen Blockade". Konservative Therapie des Prostatakarzinoms. pp. 61–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-72613-2_6. ISBN 978-3-540-17724-1.

- ^ Tunn UW, Senge T, Neumann F (1981). "Serumkonzentrationen von Testosteron und Prolaktin nach operativer und medikamentöser Kastration — eine Langzeitstudie bei Prostatakarzinom-Patienten". Verhandlungsbericht der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Urologie [Serum concentrations of testosterone and prolactin after surgical and medical castration-A long-term study in prostate cancer patients]. Vol. 32. pp. 419–421. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81706-9_123. ISBN 978-3-540-11017-0.

- ^ Baba S, Janetschek G, Wenderoth U, Jacobi GH (1981). "Beeinflussung des intraprostatischen Testosteron-Stoffwechsels durch Cyproteronazetat und Östradiolundecylat bei Patienten mit Prostatakarzinom: In vivo-Untersuchungen". Verhandlungsbericht der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Urologie [Influence of intraprostatic testosterone metabolism by cyproterone acetate and estradiol undecylate in patients with prostate cancer: in vivo studies]. Vol. 32. pp. 464–466. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81706-9_138. ISBN 978-3-540-11017-0.

- ^ a b c d Derra C (1981). Hormonprofile unter Östrogen-und Antiandrogentherapie bei Patienten mit Prostatakarzinom: Östradiolundecylat versus Cyproteronacetat [Hormone profiles under estrogen and antiandrogen therapy in patients with prostate cancer: estradiol undecylate versus cyproterone acetate] (Ph.D. thesis). Mainz, Universiẗat. OCLC 65055508. OL 24894194W.

- ^ Jacobi GH, Altwein JE (1980). "Testosterone plasma kinetics in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with estradiol undecylate, cyproterone acetate and estramustine phosphate: a preliminary report". Steroid receptors, metabolism and prostatic cancer: proceedings of a workshop of the Society of Urologic Oncology and Endocrinology, Amsterdam, 27-28 April, 1979. Vol. 494. Excerpta Medica. pp. 144–151.

- ^ Nagel R, Schillinger E, Kölln CP, Pochhammer K (1973). "Das Verhalten der Serumlipide bei Patienten mit Prostatacarcinom nach Behandlung mit Oestradiolundecylat". 24. Tagung vom 13. Bis 16. September 1972 in Hannover [The behavior of serum lipids in patients with prostate cancer after treatment with estradiol undecylate]. Verhandlungsbericht der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Urologie. Vol. 24. pp. 298–301. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80738-1_75. ISBN 978-3-540-06186-1.

- ^ Taupitz A, Otaguro K (1959). "Quantitative Examination of Serum Components After Antiandrogenic Therapy Against Prostatic Cancer" [Quantitative Examination of Serum Components after Antiandrogenic Therapy Against Prostatic Cancer: Clinical and Experimental Observation]. The Japanese Journal of Urology. 50 (3): 153–162. doi:10.5980/jpnjurol1928.50.3_153.

- ^ Götz H, Ehrmeier H (June 1971). "[Estrogens and ceruloplasmine level]" [Estrogens and ceruloplasmin levels]. Archiv für Gynäkologie. 211 (1): 204–206. doi:10.1007/BF00682878. PMID 5108847. S2CID 38378905.

- ^ a b Vermeulen A (1977). "Transport and distribution of androgens at different ages". In Martini L, Motta M (eds.). Androgens and Antiandrogens. New York: Raven Press. pp. 53–65. ISBN 9780890041413. OCLC 925036459.

In postmenopausal women, however, estrogen administration does not change the androgen levels significantly. The increase in TeBG capacity after injection of 100 mg Progynon Depot® (estradiol undecylate), therefore, is unequivocally the result of the estrogens: 6 days after injection, when plasma estradiol levels varied between 30 ng/100 ml [300 pg/mL] and 60 ng/100 ml [600 pg/mL], TeBG levels were nearly doubled (1.4–1.6 ✕ 107 M), whereas the free testosterone fraction decreased from 1.25% to 0.70%.

- ^ Saleh FM (11 February 2009). Sex Offenders: Identification, Risk Assessment, Treatment, and Legal Issues. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-0-19-517704-6.

- ^ Salam MA (2003). Principles & Practice of Urology: A Comprehensive Text. Universal-Publishers. pp. 684–. ISBN 978-1-58112-412-5.

- ^ Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA (25 August 2011). Campbell-Walsh Urology: Expert Consult Premium Edition: Enhanced Online Features and Print, 4-Volume Set. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2938–. ISBN 978-1-4160-6911-9.

- ^ Kjeld JM, Puah CM, Kaufman B, Loizou S, Vlotides J, Gwee HM, et al. (November 1979). "Effects of norgestrel and ethinyloestradiol ingestion on serum levels of sex hormones and gonadotrophins in men". Clinical Endocrinology. 11 (5): 497–504. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1979.tb03102.x. PMID 519881. S2CID 5836155.

- ^ a b c d Vermeulen A (1975). "Longacting steroid preparations". Acta Clinica Belgica. 30 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1080/17843286.1975.11716973. PMID 1231448.

- ^ a b c Leyendecker G, Geppert G, Nocke W, Ufer J (May 1975). "[Estradiol-17beta, estrone, LH and FSH in serum after administration of estradiol-17beta, estradiolbenzoate, estradiol-valeriate and estradiol-undecylate in the female (author's transl)]" [Estradiol 17β, estrone, LH and FSH in serum after administration of estradiol 17β, estradiol benzoate, estradiol valeriate and estradiol undecylate in the female]. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde (in German). 35 (5): 370–374. PMID 1150068.

Estradiol 17β, estradiol benzoate, estradiol valerianate, and estradiol undecylate were injected intravenously and intramuscularly to postmenopausal woman and to female castrates. Equal doses were used corresponding to 20 mg of free estradiol 17β. Estradiol 17β, estrone, FSH and LH were measured in serum by radioimmunoassay before and after application of the hormone and the estradiol esters. Thus the depot effect of the different esters could be compared.

- ^ a b c d e f g Geppert G (1975). Untersuchungen zur Pharmakokinetik von Östradiol-17β, Östradiol-Benzoat, Östradiol-Valerianat und Östradiol-Undezylat bei der Frau: der Verlauf der Konzentrationen von Östradiol-17β, Östron, LH und FSH im Serum [Studies on the pharmacokinetics of estradiol-17β, estradiol benzoate, estradiol valerate, and estradiol undecylate in women: the progression of serum estradiol-17β, estrone, LH, and FSH concentrations]. pp. 1–34. OCLC 632312599.

- ^ a b Zimmermann W, Buescher HK, Taupitz A, Thewalt K (1964). "Steroidhormonausscheidung bei Patienten mit Erkrankungen der Prostata Unter Behandlung mit Natürlichen und Synthetischen Oestrogenen" [Steroid Hormone Excretion of Patients with Diseases of the Prostate under Treatment with Natural and Synthetic Estrogens]. Acta Endocrinologica (in German). 45 (4 Suppl 90): SUPPL90:211–SUPPL90:225. doi:10.1530/acta.0.045S211. PMID 14111328.

- ^ Oriowo MA, Landgren BM, Stenström B, Diczfalusy E (April 1980). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetic properties of three estradiol esters". Contraception. 21 (4): 415–424. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(80)80018-7. PMID 7389356.

- ^ a b c Brotherton J (1976). Sex Hormone Pharmacology. Academic Press. pp. 226, 476. ISBN 978-0-12-137250-7.

- ^ a b Jucker E (8 March 2013). Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung / Progress in Drug Research / Progrès des recherches pharmaceutiques. Birkhäuser. pp. 243–. ISBN 978-3-0348-7044-3.

Estradiol undecylenate has a more protracted effect but it releases only subthreshold doses of steroid (advantage may be taken of this for the treatment of menopause).

- ^ a b c d e f Toppozada M (June 1977). "The clinical use of monthly injectable contraceptive preparations". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 32 (6): 335–347. doi:10.1097/00006254-197706000-00001. PMID 865726.

- ^ Kuhl H, Taubert HD (July 1973). "A new class of long-acting hormonal steroid preparation: synthesis of oligomeric estradiol derivatives". Steroids. 22 (1): 73–87. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(73)90072-X. PMID 4737545.

- ^ Kuhl H, Taubert HD (September 1973). "[Proceedings: New type of long-acting steroids: Synthesis and biological effect]" [A New Type of Long-Acting Steroid Preparation: Synthesis and Biological Efficacy]. Archiv für Gynäkologie. 214 (1): 127–128. doi:10.1007/BF00671087. PMID 4801412. S2CID 26261148.

- ^ Kuhl H, Auerhammer W, Taubert HD (October 1976). "Oligomeric oestradiol esters: a new class of long-acting oestrogens". Acta Endocrinologica. 83 (2): 439–448. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0830439. PMID 989671.

- ^ a b Kicovic PM, Luisi M, Franchi F, Alicicco E (July 1977). "Effects of orally administered oestradiol decanoate on plasma oestradiol, oestrone and gonadotrophin levels, vaginal cytology, cervical mucus and endometrium in ovariectomized women". Clinical Endocrinology. 7 (1): 73–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1977.tb02941.x. PMID 880735. S2CID 13639429.

- ^ a b Luisi M, Kicovic PM, Alicicco E, Franchi F (April 1978). "Effects of estradiol decanoate in ovariectomized women". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 1 (2): 101–106. doi:10.1007/BF03350355. PMID 755846. S2CID 38187367.

- ^ a b Chaudhury RR (1 January 1981). Pharmacology of Estrogens. Elsevier Science & Technology Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-08-026869-9.

- ^ Jameson JL, De Groot LJ (25 February 2015). Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2387–. ISBN 978-0-323-32195-2.

- ^ Nieschlag E, Behre HM (6 December 2012). Testosterone: Action - Deficiency - Substitution. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-3-642-72185-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Leyendecker G, Geppert G, Nocke W, Ufer J (May 1975). "[Estradiol-17beta, estrone, LH and FSH in serum after administration of estradiol-17beta, estradiolbenzoate, estradiol-valeriate and estradiol-undecylate in the female (author's transl)]" [Estradiol 17β, estrone, LH and FSH in serum after administration of estradiol 17β, estradiol benzoate, estradiol valeriate and estradiol undecylate in the female]. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde (in German). 35 (5): 370–374. PMID 1150068.

- ^ Burdock GA (1997). Encyclopedia of Food and Color Additives. CRC Press. pp. 2870–. ISBN 978-0-8493-9412-6.

- ^ Junkmann K (1957). "Long-acting steroids in reproduction". Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 13: 389–419, discussion 419–28. PMID 13477813.

- ^ Junkmann K, Witzel H (1957). "[Chemistry and pharmacology of steroid hormone esters]" [Chemistry and pharmacology of steroid hormone esters]. Zeitschrift für Vitamin-, Hormon- und Fermentforschung (in German). 9 (1–2): 97–143 contd. PMID 13531579. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^ Armstrong NA, James KC (1980). "Drug release from lipid-based dosage forms. I". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 6 (3–4): 185–193. doi:10.1016/0378-5173(80)90103-9.

- ^ Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, et al. (1953). "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension" [Over protracted effective estrogens]. Pulmonary Circulation (in German). 10 (1). doi:10.1007/BF00246561. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015. S2CID 20753905.

- ^ "17-undecenoate of estradiol".

- ^ Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, et al. (1967). "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation. 10 (1): 107–127. doi:10.1080/00224496709550519. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015.

- ^ von Bruchhausen F, Dannhardt G, Ebel S, Frahm AW, Hackenthal E, Holzgrabe U (2 July 2013). Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis: Band 8: Stoffe E-O. Springer-Verlag. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-3-642-57994-3.

- ^ Boschann HW (July 1958). "Observations of the role of progestational agents in human gynecologic disorders and pregnancy complications". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 71 (5): 727–752. Bibcode:1958NYASA..71..727B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb46803.x. PMID 13583829.

- ^ Bishop PM (1962). Chemistry of the Sex Hormones. Thomas. p. 78.

- ^ a b el-Mahgoub S, Karim M (February 1972). "Depot estrogen as a monthly contraceptive in nulliparous women with mild uterine hypoplasia". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 112 (4): 575–576. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(72)90319-5. PMID 5008627.

- ^ a b Toppozada MK (1983). "Monthly Injectable Contraceptives". In Goldsmith A, Toppozada M (eds.). Long-Acting Contraception. pp. 93–103. OCLC 35018604.

- ^ Toppozada MK (April 1994). "Existing once-a-month combined injectable contraceptives". Contraception. 49 (4): 293–301. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)90029-9. PMID 8013216.

- ^ Kadam SS (July 2007). Principles of Medicinal Chemistry Volume 2. Pragati Books Pvt. Ltd. pp. 381–. ISBN 978-81-85790-03-9.

- ^ Beck LR, Cowsar DR, Pope VZ (July 1980). "Long-acting steroidal contraceptive systems" (PDF). Research Frontiers in Fertility Regulation. 1 (1): 1–16. PMID 12179628. S2CID 13863575.

- ^ Karim M, el-Mahgoub S (July 1971). "Conception control by cyclic injections of norethisterone enanthate and estradiol unducelate". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 110 (5): 740–742. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(71)90268-7. PMID 5563241.

![Estradiol levels after a single intramuscular injection of 10 mg estradiol valerate in oil or 100 mg estradiol undecylate in oil both in 4 individuals each.[61] Subject characteristics and assay method were not described.[61] Source was Vermeulen (1975).[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Estradiol_levels_after_a_single_intramuscular_injection_of_10_mg_estradiol_valerate_and_100_mg_estradiol_undecylate.png/400px-Estradiol_levels_after_a_single_intramuscular_injection_of_10_mg_estradiol_valerate_and_100_mg_estradiol_undecylate.png)

![Estradiol levels after a short intravenous infusion of 20 mg estradiol in aqueous solution or an intramuscular injection of equimolar doses of estradiol esters in oil solution in 3 postmenopausal women each.[82][96] Assays were performed using radioimmunoassay with chromatographic separation.[82][96] Sources were Geppert (1975) and Leyendecker et al. (1975).[82][96]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Estradiol_levels_after_injections_of_estradiol%2C_estradiol_benzoate%2C_estradiol_valerate%2C_and_estradiol_undecylate_in_women.png/381px-Estradiol_levels_after_injections_of_estradiol%2C_estradiol_benzoate%2C_estradiol_valerate%2C_and_estradiol_undecylate_in_women.png)

![Estradiol, testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels with an intramuscular injection of 32.3 mg estradiol undecylate in oil in 3 postmenopausal women.[82][96] Assays were performed using radioimmunoassay with chromatographic separation.[96][82] Sources were Geppert (1975) and Leyendecker et al. (1975).[82][96]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Hormone_levels_with_an_intramuscular_injection_of_estradiol_undecylate_in_postmenopausal_women.png/400px-Hormone_levels_with_an_intramuscular_injection_of_estradiol_undecylate_in_postmenopausal_women.png)

![Estradiol, testosterone, and prolactin levels with 100 mg/month estradiol undecylate in oil by intramuscular injection in 14 to 28 men with prostate cancer.[65] A follow-up of the study with more men and with additional hormones was also subsequently published.[70] Sources were Jacobi & Altwein (1979) and Derra (1981).[65][70]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Estradiol%2C_testosterone%2C_and_prolactin_levels_during_therapy_with_100_mg_per_month_estradiol_undecylate_in_men_with_prostate_cancer.png/363px-Estradiol%2C_testosterone%2C_and_prolactin_levels_during_therapy_with_100_mg_per_month_estradiol_undecylate_in_men_with_prostate_cancer.png)