Banpresto

| |

Headquarters in Shinagawa, Tokyo | |

Native name | 株式会社バンプレスト |

|---|---|

Romanized name | Kabushiki gaisha Banpuresuto |

| Formerly |

|

| Company type | Subsidiary |

| Industry | Video games, Toys |

| Founded | April 30, 1977[a] |

| Founder | Yasushi Matsuda |

| Defunct | April 1, 2008[b] |

| Fate | Merged with Namco Bandai Games, now in-name only. |

| Headquarters | Shinagawa, Tokyo |

Area served | Japan |

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Revenue | |

| Owner |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | banpresto.co.jp |

| Footnotes / references "English Company Profile". Japan: Banpresto. 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2020. | |

Banpresto Co., Ltd.[c] (formerly Coreland Technology Inc.) was a Japanese video game developer and publisher headquartered in Shinagawa, Tokyo. It had a branch in Hong Kong named Banpresto H.K., which was headquartered in the New Territories. Banpresto was a partly-owned subsidiary of toymaker Bandai from 1989 to 2006, and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bandai Namco Holdings from 2006 to 2008. In addition to video games, Banpresto produced toys, keyrings, apparel, and plastic models.

Banpresto was founded by Japanese businessman Yasushi Matsuda as Hoei International in April 1977. Its poor reputation led to its name being changed to Coreland Technology in 1982, becoming a contractual developer for companies such as Sega. Coreland was majority-acquired by Bandai in 1989 following severe financial difficulties and renamed Banpresto, becoming Bandai's arcade game division. Banpresto focused primarily on producing games with licensed characters, such as Ultraman and Gundam. Its sharing of Bandai's library of popular characters allowed the company to become one of Japan's largest game publishers in the 1990s.

The company's first hit was the Family Computer role-playing game (RPG) SD Battle Ōzumō: Heisei Hero Basho in 1990. The tactical RPG Super Robot Wars became one of Banpresto's biggest hits, spawning an extensive franchise with several sequels, spin-offs, and other forms of media. Banpresto was negatively impacted by the Japanese recession during the late 1990s, as well as a failed merger between Bandai and Sega in 1997, as it began enduring several financial losses. In 2006, Banpresto became a wholly-owned subsidiary of the entertainment conglomerate Bandai Namco Holdings. It continued producing games until 2008 when it was absorbed by Namco Bandai Games, and its toy and arcade divisions were spun-off into an unrelated company that carried the same name.

Banpresto produced several successful video game franchises, including Super Robot Wars, Compati Hero, Sailor Moon, Summon Night, and Another Century's Episode. It also operated amusement facilities across Japan, including Hanayashiki, as well as producing model kits, stuffed toys, and UFO catcher prizes. Banpresto has been credited for contributing to the rise in popularity of crossover video games and licensed characters for arcades, though the quality of its creative output has been criticized.

History

[edit]Origins and acquisition by Bandai (1977–1989)

[edit]In April 1977, Japanese businessman Yasushi Matsusa established Hoei Sangyo Co. Ltd. (Hoei International) in Tanashi, Tokyo.[1][2] His business began as a manufacturer of arcade cabinets for other companies, as Japan's coin-operated game industry had seen considerable economic growth throughout the decade. In addition to distributing games from other manufacturers across the country, Hoei Sangyo also began production of its own games in-house, the majority being clones of other popular games like Space Invaders.[1] Matsusa's business established a relationship with Esco Trading, a company formed by Sega president Hayao Nakayama, which gave the latter the rights to distribute Hoei Sangyo's video games to other parts of Japan.[3] Hoei Sangyo released its first original video game in 1981, Jump Bug, an early side-scrolling platform game released outside Japan by Rock-Ola.[4][5]

Hoei Sangyo was reorganized into Coreland Technology Inc. in June 1982, where it became a contractor company that developed games for other companies.[1] One of its first projects was Pengo, which was released the same year by Sega. Pengo was successful arcades and lead to several sequels and home conversions.[6] Coreland also designed games such as 4-D Warriors and I'm Sorry for Sega,[7][8] and Black Panther for Konami.

In the late 1980s, Coreland established a partnership with toy company Bandai, known for its model kits and action figures based on popular characters like Mobile Suit Gundam.[9] At the time, Bandai was suffering from numerous financial difficulties as a result of the slumping Japanese toy market affecting the demand for its products. Coreland's positive track record was the primary reason for the partnership, as Bandai hoped it would allow itself to secure a stronghold in the coin-op industry.[10] However, Coreland was undergoing its own financial constraints, having accumulated more than ¥1.5 billion in debt due to poor sales. As contractual agreements prevented Bandai from backing out of its deal, it chose to majority-acquire the company in February 1989.[10] Coreland was reorganized again into Banpresto; the name came from a portmanteau of "Bandai" and "presto", a word used to describe magic. Yukumasa Sugiara, a member of Bandai's board of directors, became the company's president.[10]

Super Robot Wars and expansion (1989–1996)

[edit]Banpresto underwent significant changes as a result of Bandai's acquisition of the company. With Banpresto becoming Bandai's arcade game division, Banpresto was given the exclusive rights to use Bandai-owned characters for video arcade games and children's rides. It was also allowed to produce games for home video game consoles, such as the successful Nintendo Family Computer (Famicom); Banpresto received strict orders to not release any games that could compete with those from Bandai.[11] One of the company's first projects was SD Battle Ōzumō: Heisei Hero Basho, a crossover for the Famicom featuring "super-deformed" interpretations of Gundam, Ultraman, and Kamen Rider. It is often credited as the first video game to cross over characters from other forms of media.[12] Heisei Hero Basho was developed by Banpresto staff as a congratulatory gift to Sugiura shortly after assuming role of company president.[11] Beginning April 1990, the company supplied video arcades with prizes for UFO catchers and merchandiser machines, such as those designed after Ultraman and Kamen Rider characters. Over 70 million were sold in the year 1990 and contributed to Banpresto's ¥30 million capital increase.

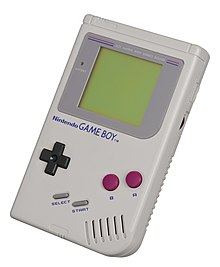

In April 1991, Banpresto introduced Super Robot Wars, a tactical role-playing game for the Game Boy.[13][14] Developed by external studio WinkySoft,[15] it was a spiritual successor to its Compati Hero series of games, crossing over popular mecha licenses like Getter Robo and Mazinger-Z.[16] Super Robot Wars was a commercial success, attributed to its release during the popularity of mecha anime in the early half of the decade.[16] It became one of the company's most-successful games, spawning a multi-million-selling franchise with several sequels, remakes, and other forms of media.[16][14] Super Robot Wars is considered important and influential for the genre, and contributed to the early success of the SD Gundam media franchise.[14] As of 2016, the Super Robot Wars series has sold over 16 million games across all available platforms.[17] Banpresto also began producing children's rides, using the likenesses of characters such as Anpanman, Super Mario, and Thomas the Tank Engine.[18]

By 1992, Banpresto was worth ¥1.4 billion yen.[2] The company began expanding its operations as a result, starting with the establishment of Sanotawa, a sales and distribution network subsidiary, in February. Banpresto found additional success in arcades with the release of Ugougo Luga, a stuffed toy that sold over 2.6 million by the end of the year. The company continued to develop and publish video games for home consoles. Among its most successful releases was Super Puyo Puyo, a Super Famicom conversion of Compile's Puyo Puyo series that sold over one million copies.[19] In February 1994, Banpresto established Banpre Kikaku, Ltd. in Kita, Osaka, which became its primary video game development division.[20] As Banpresto was largely a publisher of games by other studios, the move allowed it to experiment with original game concepts and handle development of video games in-house. In addition, Banpre Kikaku also served as a second office, and assisted in its parent company's sales programs and product distribution. Unifive, a producer of merchandiser games, became a wholly-owned subsidiary in March as part of the company's continuing expansion in the arcade industry. Banpresto began to spread its operations throughout other parts of Asia; Banpresto H.K. was founded in Hong Kong in June to import and distribute Banpresto-developed goods across the country.

Restructuring and continuing expansion (1996–2005)

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

In January 1996, Banpresto assisted in the founding of the Computer Entertainment Software Association (CESA), an organization funded by other game companies to allow for firm communications between each other.[21] The company continued to publish games by external companies, including Gazelle's Air Gallet and Fill-in-Cafe's Panzer Bandit.

Namco Bandai takeover and dissolution (2005—2008)

[edit]In September 2005, Bandai merged with fellow game company Namco to establish a new entertainment conglomerate, Namco Bandai Holdings. Namco and Bandai's video game operations were merged and transferred to a new subsidiary, Namco Bandai Games, in March 2006.[22][23] Banpresto became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Namco Bandai Holdings upon the formation of Namco Bandai Games,[24] however the merge had little effect on the company itself.[22] The company reported considerable financial success following the merge in April, as its net income forecast exceeded the expected ¥1.6 billion to ¥2.1 billion.[25] The company continued to produce games based on licensed properties, notably Crayon Shin-Chan, as well as selling arcade game equipment and maintaining its video arcade chains.[25][26]

In November 2007, Namco Bandai Holdings announced that Banpresto's video game development would be merged with Namco Bandai Games, with the latter assuming control of all Banpresto-owned franchises.[27] The merge took place on April 1, 2008, with Banpresto being reorganized as a producer of toys and prize machines for Japan.[27] Pleasure Cast and Hanayashiki subsequently became subsidiaries of Namco,[27] while Banpresoft became a wholly-owned division of Namco Bandai Games.[citation needed] Until February 2014, Namco Bandai Games continued using the Banpresto label on several of its games to signify the brand's legacy.[28]

The Banpresto name continued to be used as the name of a Bandai Namco division until 2019, when it was absorbed into the then-recently formed Bandai Spirits division of Bandai, relegating it into a brand of high-end figures based on licensed products.[citation needed]

Games

[edit]Hoei/Coreland

[edit]| Title | Release year | Distributor(s) | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Bug | 1981 | Sega | Arcade |

| Pengo | 1982 | ||

| SWAT[29] | 1984 | ||

| Gombe's I'm Sorry | 1985 | Sega | |

| Seishun Scandal | 1986 | ||

| WEC Le Mans | 1986 | Konami | |

| Cyber Tank[30][31] | 1988 | Taito |

Banpresto

[edit]| Title | Platform(s) | Release date |

|---|---|---|

| SD Lupin the 3rd: Operation to Break the Safe | Game Boy | April 13, 1990 |

| SD Battle Ōzumō: Heisei Hero Basho | Family Computer | April 20, 1990 |

| SD Hero Soukessen: Taose! Aku no Gundan | Family Computer | July 7, 1990 |

| Ranma ½ | Game Boy | July 28, 1990 |

| SD Sengoku Bushou Retsuden: Rekka no Gotoku Tenka wo Nusure! | Family Computer | September 8, 1990 |

| Kininkou Maroku Oni | Game Boy | December 8, 1990 |

| Hissatsu Shigotonin | Family Computer | December 15, 1990 |

| SD the Great Battle | Super Famicom | December 29, 1990 |

| Super Robot Wars | Game Boy | April 20, 1991 |

| Battle Dodge Ball | Super Famicom | July 20, 1991 |

| Game Boy | October 16, 1992 | |

| Super Puyo Puyo | Super Famicom | December 10, 1993 |

| Puyo Puyo | Game Boy | July 31, 1994 |

| Battle Pinball | Super Famicom | February 24, 1995 |

| Super Tekkyuu Fight! | Super Famicom | September 15, 1995 |

| Magna Carta Portable | PSP | May 25, 2006 |

| Crayon Shin-chan: Saikyou Kazoku Kasukabe King Wii | Wii | December 2, 2006 |

| Gintama: Gintoki vs. Hijikata | Nintendo DS | December 14, 2006 |

| Crayon Shin-Chan: Arashi wo Yobu Cinema Land - Kachinko Gachinko Daikatsugeki! | Nintendo DS | March 20, 2008 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Horowitz, Ken (22 June 2018). The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1476672250.

- ^ a b "Corporate History". www.banpresto.co.jp. Japan: Banpresto. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 October 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Smith, Alexander (2019). They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Volume I. CRC Press. p. 433. ISBN 9781138389908.

- ^ "Hoei Grants "Jump Bug" —Rock-Ola for U.S.A. and Sega for Other Areas—". Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 179. Amusement Press. 15 December 1981. p. 30.

- ^ "Jump Bug - Videogame by Rock-Ola Mfg. Corp". Killer List of Videogames. International Arcade Museum. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Bobinator (17 August 2015). "Pengo". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "4-D Warriors - Videogame by Sega". Killer List of Videogames. International Arcade Museum. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Plasket, Michael (16 October 2015). "I'm Sorry". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Wild, Kim (2007). "Retroinspection: WonderSwan". Retro Gamer (36). Imagine Publishing: 68–71. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ a b c "Bandai Buys Coreland To Make Games" (PDF). No. 351. Japan: Amusement Press. Game Machine. 1 March 1989. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b 第一章 拡大するアニメ・ビジネス 二.古いキャラクターの価値 ●版権窓口が異なる新旧のキャラクターを集めてヒット (in Japanese). Nikkei Business Publications. 17 May 1999. p. 28. ISBN 4-8222-2550-X.

- ^ Lopes, Gonçalo (12 March 2018). "Zany Super Famicom Great Battle Series Gets Translated Into English". Nintendo Life (in Japanese). Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "スーパーロボット大戦 (ゲームボーイ)". Famitsu (in Japanese). Kadokawa Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Barder, Ollie (22 April 2014). "All is fair in love and Super Robot Wars". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Barder, Ollie (1 December 2015). "The End Of An Era As Winkysoft Files For Bankruptcy". Forbes. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Hamamura, Hirokazu. 『浜村通信 ゲーム業界を読み解く』 (Hanamura Tsūshin: Gēmu Gyōkai o Yomitoku, "Hanamura Journal: Deciphering the Video Game Industry") (in Japanese). Enterbrain. pp. 203–206.

- ^ "「スーパーロボット大戦」シリーズ累計出荷本数1,600万本突破。第1作のHDリメイク版がPS Storeで販売開始" [Cumulative shipment of "Super Robot Wars" series exceeded 16 million. The first HD remake version is now available on the PS Store]. 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). Aetas. 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "ミニ定置回転式 - バンプレスト「アンパンマン」" (PDF) (in Japanese). No. 497. Amusement Press. Game Machine. 15 June 1995. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Japan Platinum Game Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "バンプレソフトとベック、4月1日付で合併しB.B.スタジオに". GameBusiness (in Japanese). IID. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Home Vid Manufacturers Set Up New Association" (PDF) (in Japanese). No. 510. Amusement Press. Game Machine. 1 January 1996. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b Niizumi, Hirohiko (13 September 2005). "Bandai and Namco outline postmerger strategy". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Karlin, David (31 March 2006). "Bandai and Namco Finalize Merger Details". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (February 23, 2006). "Bandai Namco Absorbs Banpresto". IGN. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Tochen, Dan (26 April 2006). "Banpresto upgrades profit forecast". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "ニユースダイジェスト". Game Machine (in Japanese). Amusement Press. March 23, 2005. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Gantayat, Anoop (8 November 2007). "Sayonara, Banpresto". IGN. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ ITmedia Staff (5 February 2014). "「バンダイナムコゲームス」にレーベル統一 ゲームから「バンダイ」「ナムコ」「バンプレスト」消滅". ITmedia (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Sotenga (September 28, 2014). "SWAT". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Cyber Tank". Media Arts Database. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Openshaw, Mary (March 1990). "Paris Says Oui! Pins, video and — surprise! — poll all shine at best Paris show ever". RePlay. Vol. 15, no. 6. pp. 134–5.

External links

[edit]- Japanese companies established in 1977

- Amusement companies of Japan

- Companies disestablished in 2008

- Entertainment companies of Japan

- Former Bandai Namco Holdings subsidiaries

- Japanese brands

- Publishing companies established in 1977

- Toy companies of Japan

- Video game companies established in 1977

- Video game development companies

- Video game publishers