Elephantidae

| Elephantidae Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A male Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in the wild at Bandipur National Park in India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | Elephantoidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae Gray, 1821 |

| Type genus | |

| Elephas | |

| Genera[3] | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

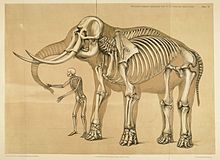

Elephantidae is a family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals collectively called elephants and mammoths. These are large terrestrial mammals with a snout modified into a trunk and teeth modified into tusks. Most genera and species in the family are extinct. Only two genera, Loxodonta (African elephants) and Elephas (Asian elephants), are living.

The family was first described by John Edward Gray in 1821,[5] and later assigned to taxonomic ranks within the order Proboscidea. Elephantidae has been revised by various authors to include or exclude other extinct proboscidean genera.

Description

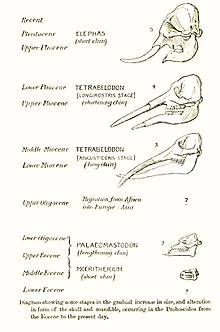

[edit]Elephantids are distinguished from more primitive proboscideans like gomphotheres by their teeth, which have parallel lophs, formed from the merger of the cusps found in the teeth of more primitive proboscideans, which are bound by cementum.[6] In later elephantids, these lophs became narrow lamellae,[7] with the number of lophs/lamellae per tooth, as well as the tooth crown height (hypsodonty) increasing over time.[8] Elephantids chew using a proal jaw movement involving a forward stroke of the lower jaws, different from the oblique movement using side to side motion of the jaws in more primitive proboscideans.[9] The most primitive elephantid Stegotetrabelodon had a long lower jaw with lower tusks and retained permanent premolars similar to many gomphotheres, while modern elephantids lack permanent premolars, with the lower jaw being shortened (brevirostrine) and lower tusks being absent.[8] Elephantids are typically sexually dimorphic, with substantially larger males, with an accelerated growth rate over a longer period of time than females. Elephantidae contains some of the largest known proboscideans, with fully-grown males of some species of mammoths and Palaeoloxodon having average body masses of 11 tonnes (24,000 lb) and 13 tonnes (29,000 lb) respectively, making them among the largest terrestrial mammals ever. One species of Palaeoloxodon, Palaeoloxodon namadicus, has been suggested to have been possibly the largest land mammal of all time, though this remains speculative due to the fragmentary nature of known remains.[10] In comparison to more primitive elephantimorphs like gomphotheres, the bodies of elephantids tend to be proportionally shorter from front to back, as well having more elongate limbs with more slender limb bones.[11]

-

Molar of Tetralophodon, a "tetralophodont gomphothere"

-

Worn molar of Stegotetrabelodon, a primitive elephantid

-

Molar of a modern African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana)

-

Tooth of Mammuthus sp.

-

Cross section through elephantid molars

Classification

[edit]

Some authors have suggested to classify the family into two subfamilies, Stegotetrabelodontinae, which is monotypic, only containing Stegotetrabelodon, and Elephantinae, containing all other elephantids.[8] Recent genetic research has indicated that Elephas and Mammuthus are more closely related to each other than to Loxodonta, with Palaeoloxodon closely related to Loxodonta. Palaeoloxodon also appears to have received extensive hybridisation with the African forest elephant, and to a lesser extent with mammoths.[12]

Living species

[edit]- Loxodonta (African)

- L. africana African bush elephant

- L. cyclotis African forest elephant

- Elephas (Asiatic)

- E. maximus Asian elephant

- E. m. maximus Sri Lankan elephant

- E. m. indicus Indian elephant

- E. m. sumatranus Sumatran elephant

- E. m. borneensis Borneo elephant

- E. maximus Asian elephant

Classification

[edit]- Elephantidae

- †Stegotetrabelodon (4 species)

- Subfamily Elephantinae

- †Primelephas (2 species)

- Elephas (7+ species)

- †Stegoloxodon (2 species)

- Loxodonta (6 species)

- †Palaeoloxodon (14+ species)

- †Phanagoroloxodon (1 species)

- †Mammuthus (10 species)

- †Stegodibelodon (1 species)

- †Selenetherium (1 species)

Evolutionary history

[edit]

Elephantids are thought to have evolved from gomphotheres, with some authors proposing the most likely ancestors to be African species of the "tetralophodont gomphothere" Tetralophodon.[13] The earliest members of the family, are known from the Late Miocene, around 9–10 million years ago.[14] The modern genera of elephants and mammoths had diverged from each other by the end of the Miocene, around 5 million years ago. Elephantids began to migrate out of Africa during the Pliocene, with mammoths and Elephas arriving in Eurasia around 3–3.8 million years ago.[15] Around 1.5 million years ago, mammoths migrated into North America.[16] At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 0.8 million years ago, Palaeoloxodon migrated out of Africa, becoming widespread across Eurasia, from Western Europe to Japan.[17] Palaeoloxodon and Mammuthus became extinct during the Late Pleistocene-Holocene, with the last population of mammoths persisting on Wrangel Island until around 4,000 years ago.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ H. T. Mackaye, M. Brunet, and P. Tassy. 2005. Selenetherium kolleensis nov. gen. nov. sp.: un nouveau Proboscidea (Mammalia) dans le Pliocène tchadien. Geobios 38(6):765-777

- ^ Kalb, J. E.; & Froehlich, D. J. (1995). "Interrelationships of Late Neogene Elephantoids: New evidence from the Middle Awash Valley, Afar, Ethiopia". Geobios. 28 (6): 727–736. Bibcode:1995Geobi..28..727K. doi:10.1016/s0016-6995(95)80068-9.

- ^ Shoshani, J.; Ferretti, M.P.; Lister, A.M.; Agenbroad, L.D.; Saegusa, H.; Mol, D.; Takahashi, K. (2007). "Relationships within the Elephantinae using hyoid characters". Quaternary International. 169–170: 174–185. Bibcode:2007QuInt.169..174S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.02.003.

- ^ Maglio, Vincent J. (1973). "Origin and Evolution of the Elephantidae". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 63 (3): 16. doi:10.2307/1006229. JSTOR 1006229.

- ^ Gray, John Edward (1821). "On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals". London Medical Repository. 15: 297–310.

- ^ Lister, Adrian M. (2013-06-26). "The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans". Nature. 500 (7462): 331–334. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..331L. doi:10.1038/nature12275. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23803767. S2CID 883007.

- ^ Saarinen, Juha; Lister, Adrian M. (2023-08-14). "Fluctuating climate and dietary innovation drove ratcheted evolution of proboscidean dental traits". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 7 (9): 1490–1502. Bibcode:2023NatEE...7.1490S. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02151-4. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 10482678. PMID 37580434.

- ^ a b c Athanassiou, Athanassios (2022), Vlachos, Evangelos (ed.), "The Fossil Record of Continental Elephants and Mammoths (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Elephantidae) in Greece", Fossil Vertebrates of Greece Vol. 1, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 345–391, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68398-6_13, ISBN 978-3-030-68397-9, S2CID 245067102, retrieved 2023-11-21

- ^ Saegusa, Haruo (March 2020). "Stegodontidae and Anancus: Keys to understanding dental evolution in Elephantidae". Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106176. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106176S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106176. S2CID 214094348.

- ^ Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950.

- ^ Bader, Camille; Delapré, Arnaud; Göhlich, Ursula B.; Houssaye, Alexandra (November 2024). "Diversity of limb long bone morphology among proboscideans: how to be the biggest one in the family". Papers in Palaeontology. 10 (6). doi:10.1002/spp2.1597. ISSN 2056-2799.

- ^ Palkopoulou, Eleftheria; Lipson, Mark; Mallick, Swapan; Nielsen, Svend; Rohland, Nadin; Baleka, Sina; Karpinski, Emil; Ivancevic, Atma M.; To, Thu-Hien; Kortschak, R. Daniel; Raison, Joy M. (2018-03-13). "A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (11): E2566 – E2574. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E2566P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720554115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5856550. PMID 29483247.

- ^ Geraads, Denis; Zouhri, Samir; Markov, Georgi N. (2019-05-04). "The first Tetralophodon (Mammalia, Proboscidea) cranium from Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (3): e1632321. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E2321G. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1632321. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 202024016.

- ^ H. Saegusa, H. Nakaya, Y. Kunimatsu, M. Nakatsukasa, H. Tsujikawa, Y. Sawada, M. Saneyoshi, T. Sakai Earliest elephantid remains from the late Miocene locality, Nakali, Kenya Scientific Annals, School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece VIth International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives, vol. 102, Grevena -Siatista, special volume (2014), p. 175

- ^ Iannucci, Alessio; Sardella, Raffaele (March 2023). "What Does the "Elephant-Equus" Event Mean Today? Reflections on Mammal Dispersal Events around the Pliocene-Pleistocene Boundary and the Flexible Ambiguity of Biochronology". Quaternary. 6 (1): 16. doi:10.3390/quat6010016. hdl:11573/1680082. ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ Lister, A. M.; Sher, A. V. (November 13, 2015). "Evolution and dispersal of mammoths across the Northern Hemisphere". Science. 350 (6262): 805–809. Bibcode:2015Sci...350..805L. doi:10.1126/science.aac5660. PMID 26564853. S2CID 206639522.

- ^ Lister, Adrian M. (2004), "Ecological Interactions of Elephantids in Pleistocene Eurasia", Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor, Oxbow Books, pp. 53–60, ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4, retrieved 2020-04-14

- ^ Arppe, Laura; Karhu, Juha A.; Vartanyan, Sergey; Drucker, Dorothée G.; Etu-Sihvola, Heli; Bocherens, Hervé (October 2019). "Thriving or surviving? The isotopic record of the Wrangel Island woolly mammoth population". Quaternary Science Reviews. 222: 105884. Bibcode:2019QSRv..22205884A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105884. hdl:10138/309133. S2CID 203103403.

External links

[edit] Media related to Elephantidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Elephantidae at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Elephantidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Elephantidae at Wikispecies