Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady

| Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady | |

|---|---|

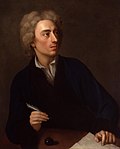

| by Alexander Pope | |

Title and opening lines in the first edition of Works (1717) | |

| First published in | The Works of Mr Alexander Pope (1717) |

| Metre | Iambic pentameter |

| Full text | |

"Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady", also called "Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady", is a poem in heroic couplets by Alexander Pope, first published in his Works of 1717.[1] Though only 82 lines long, it has become one of Pope's most celebrated pieces.

Synopsis

[edit]The work begins with the poet asking what ghost beckons him onward with its "bleeding bosom gor'd"; it is the spirit of an unnamed woman (the "lady" of the title) who acted "a Roman's part" (i.e., committed suicide) due to loving "too well." The speaker eulogizes her sacrifice and then for several lines berates and curses her uncle (who is also her guardian) for being a "mean deserter of [his] brother's blood" and having no compassion on the lady. There follows a description of her foreign burial in a "humble grave" unattended by friends and relatives, which Pope sums up in the striking couplet:

A heap of dust alone remains of thee;

'Tis all thou art, and all the proud shall be![1]— lines 73-74

The concluding lines contain the speaker's application of this lesson of mortality to himself: someday he too will die and the last thought of the lady will be torn from him as he passes away.

Subject

[edit]Frederic Harrison believed the subject of the work to be Elizabeth Gage (died 1724), wife of John Weston (died 1730) of Sutton Place, Surrey. She was the sister of Thomas Gage, 1st Viscount Gage (died 1754). Harrison derives his opinion from a note of Pope's appended to a letter of his to Mrs Weston, and states the story of the poem to be pure imagination: "Mrs Weston was separated from her husband, but she returned and lived in peace. She did not die abroad, friendless and by suicide, but in the bosom of her family, by natural causes, and in her own home. She was in fact buried in the (Weston) family vault in Guildford in 1724, eleven years after Pope's outburst".[2]

Reception

[edit]

Readers' reactions to this work have been varied, and some have offered severe criticisms. John Wesley in "Thoughts on the Character and Writings of Mr. Prior" (1782) compared the poet Matthew Prior with Pope, mostly to the detriment of the latter; in this essay, Wesley says of Pope:

As elegant a piece as he ever wrote was, "Verses to the Memory of an unfortunate Lady." But was ever any thing more exquisitely injudicious? First, what a subject! An eulogium on a self-murderer! And the execution is as bad as the design: it is a commendation not only of the person, but the act![3]

Wesley illustrates this by quoting the lines:

Is it, in heav'n, a crime to love too well?

To bear too tender, or too firm a heart,

To act a Lover's or a Roman's part?[1]— lines 6-8

Most of Wesley's grounds for criticism are moral: since—as he would consider self-evident—suicide is an evil act that affronts God and causes the doer to go to hell, the glorification of the lady's act in this poem is seriously objectionable. (This did not, however, prevent him from quoting the couplet given above in his Journal on more than one occasion [see December 5, 1750 and July 4, 1786].) Samuel Johnson in his Lives of the Poets also faulted the "Elegy" on similar grounds, referring to "the illaudable singularity of treating suicide with respect."

A different kind of criticism, one on artistic grounds, is made by Maynard Mack in his important biography Alexander Pope: A Life. Mack acknowledges that there are beautiful passages in the poem, but also finds that it is marked by a certain incoherence between elements and attitudes which are not fully reconciled, such as the idea of Roman suicide vs. that of Christian burial, or the strange curse on the uncle and all his posterity for his unspecified crimes. Johnson also anticipates some of this artistic censure in judging that "the tale [in the poem] is not skilfully told."

In spite of such objections, most critics would not deny the emotional impact of Pope's "Elegy," and even Johnson acknowledges that the poem "must be allowed to be written in some parts with vigorous animation, and in others with gentle tenderness." It is frequently included in anthologies that include Pope's best-known poems or those of his era, and the "Elegy's" effective phrasing is often remembered and quoted.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Pope 1963, pp. 262–264.

- ^ Harrison, Frederic. Annals of an Old Manor House: Sutton Place, Guildford. London, 1899, p.141

- ^ Wesley, John (1827). The Works of the Rev. John Wesley. Vol. X. New York: J. & J. Harper. pp. 180-181.

Sources

[edit]- Pope, Alexander (1963). Butt, John (ed.). The Poems of Alexander Pope (a one-volume edition of the Twickenham text ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300003404. OCLC 855720858.

- John Wesley, "Thoughts on the Character and Writings of Mr. Prior" and "Journals" in Wesley's Works as given in "The Master Christian Library" v. 8 (by Ages Software).

- Maynard Mack, Alexander Pope: A Life. NY: Norton, 1985, pp. 312–19. ISBN 0-393-30529-5.

- Samuel Johnson, "Pope" [partial excerpt from Lives of the Poets], in Donald Greene, ed., Samuel Johnson: The Major Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984, p. 739. ISBN 0-19-284042-8.

External links

[edit]- Project Gutenberg e-text of The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, Volume 1 (includes the "Elegy").