Unit record equipment

Starting at the end of the nineteenth century, well before the advent of electronic computers, data processing was performed using electromechanical machines collectively referred to as unit record equipment, electric accounting machines (EAM) or tabulating machines.[1][2][3][4] Unit record machines came to be as ubiquitous in industry and government in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century as computers became in the last third. They allowed large volume, sophisticated data-processing tasks to be accomplished before electronic computers were invented and while they were still in their infancy. This data processing was accomplished by processing punched cards through various unit record machines in a carefully choreographed progression.[5] This progression, or flow, from machine to machine was often planned and documented with detailed flowcharts that used standardized symbols for documents and the various machine functions.[6] All but the earliest machines had high-speed mechanical feeders to process cards at rates from around 100 to 2,000 per minute, sensing punched holes with mechanical, electrical, or, later, optical sensors. The operation of many machines was directed by the use of a removable plugboard, control panel, or connection box.[7] Initially all machines were manual or electromechanical. The first use of an electronic component was in 1937 when a photocell was used in a Social Security bill-feed machine.[8]: 65 Electronic components were used on other machines beginning in the late 1940s.

The term unit record equipment also refers to peripheral equipment attached to computers that reads or writes unit records, e.g., card readers, card punches, printers, MICR readers.

IBM was the largest supplier of unit record equipment and this article largely reflects IBM practice and terminology.

History

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]In the 1880s Herman Hollerith was the first to record data on a medium that could then be read by a machine. Prior uses of machine readable media had been for lists of instructions (not data) to drive programmed machines such as Jacquard looms and mechanized musical instruments. "After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards [...]".[9] To process these punched cards, sometimes referred to as "Hollerith cards", he invented the keypunch, sorter, and tabulator unit record machines.[10][11] These inventions were the foundation of the data processing industry. The tabulator used electromechanical relays to increment mechanical counters. Hollerith's method was used in the 1890 census. The company he founded in 1896, the Tabulating Machine Company (TMC), was one of four companies that in 1911 were amalgamated in the forming of a fifth company, the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, later renamed IBM.

Following the 1900 census a permanent Census bureau was formed. The bureau's contract disputes with Hollerith led to the formation of the Census Machine Shop where James Powers and others developed new machines for part of the 1910 census processing.[12] Powers left the Census Bureau in 1911, with rights to patents for the machines he developed, and formed the Powers Accounting Machine Company.[13] In 1927 Powers' company was acquired by Remington Rand.[14] In 1919 Fredrik Rosing Bull, after examining Hollerith's machines, began developing unit record machines for his employer. Bull's patents were sold in 1931, constituting the basis for Groupe Bull.

These companies, and others, manufactured and marketed a variety of general-purpose unit record machines for creating, sorting, and tabulating punched cards, even after the development of computers in the 1950s. Punched card technology had quickly developed into a powerful tool for business data-processing.

Timeline

[edit]

- 1884: Herman Hollerith files a patent application titled "Art of Compiling Statistics"; granted U.S. patent 395,782 on January 8, 1889.

- 1886: First use of tabulating machine in Baltimore's Department of Health.[15]

- 1887: Hollerith files a patent application for an integrating tabulator (granted in 1890).[16]

- 1889: First recorded use of integrating tabulator in the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army.[16]

- 1890-1895: U.S. Census, Superintendents Robert P. Porter 1889-1893 and Carroll D. Wright 1893-1897, tabulations are done using equipment supplied by Hollerith.

- 1896: The Tabulating Machine Company founded by Hollerith, trade name for products is Hollerith

- 1901: Hollerith Automatic Horizontal Sorter[17]

- 1904: Porter, having returned to England, forms The Tabulator Limited (UK) to market Hollerith's machines.[18]

- 1905: Hollerith reincorporates the Tabulating Machine Company as The Tabulating Machine Company

- 1906: Hollerith Type 1 Tabulator, the first tabulator with an automatic card feed and control panel.[19]

- 1909: The Tabulator Limited renamed as British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM).

- 1910: Tabulators built by the Census Machine Shop print results.[20]

- 1910: Willy Heidinger, an acquaintance of Hollerith, licenses Hollerith’s The Tabulating Machine Company patents, creating Dehomag in Germany.

- 1911: Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR), a holding company, formed by the amalgamation of The Tabulating Machine Company and three other companies.

- 1911: James Powers forms Powers Tabulating Machine Company, later renamed Powers Accounting Machine Company. Powers had been employed by the Census Bureau to work on tabulating machine development and was given the right to patent his inventions there. The machines he developed sensed card punches mechanically, as opposed to Hollerith's electric sensing.[21][22]

- 1912: The first Powers horizontal sorting machine.[23]

- 1914: Thomas J. Watson hired by CTR.

- 1914: The Tabulating Machine Company produces 2 million punched cards per day.[24]

- 1914: The first Powers printing tabulator.[25]

- 1915 Powers Tabulating Machine Company establishes European operations through the Accounting and Tabulating Machine Company of Great Britain Limited.[26][8]: 259 [27]

- 1919: Fredrik Rosing Bull, after studying Hollerith's machines, constructs a prototype 'ordering, recording and adding machine' (tabulator) of his own design. About a dozen machines were produced during the following several years for his employer.[25]

- 1920s: Early in this decade punched cards began use as bank checks.[28][29]

- 1920: BTM begins manufacturing its own machines, rather than simply marketing Hollerith equipment.

- 1920: The Tabulating Machine Company's first printing tabulator, the Hollerith Type 3.[30]

- 1921: Powers-Samas develops the first commercial alphabetic punched card representation.[31]

- 1922: Powers develops an alphabetic printer.[25]

- 1923: Powers develops a tabulator that accumulates and prints both sub and grand totals (rolling totals).[23]

- 1923: CTR acquires 90% ownership of Dehomag, thus acquiring patents developed by them.[32]

- 1924: Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) renamed International Business Machines (IBM). There would be no IBM-labeled products until 1933.

- 1925: The Tabulating Machine Company's first horizontal card sorter, the Hollerith Type 80, processes 400 cards/min.[25][33]

- 1927: Remington Typewriter Company and Rand Kardex combine to form Remington Rand. Within a year, Remington Rand acquires the Powers Accounting Machine Company.[14]

- 1928: The Tabulating Machine Company's first tabulator that could subtract, the Hollerith Type IV tabulator.[34] The Tabulating Machine Company begins its collaboration with Benjamin Wood, Wallace John Eckert and the Statistical Bureau at Columbia University.[35][8]: 67 The Tabulating Machine Company's 80-column card introduced. Comrie uses punched card machines to calculate the motions of the moon. This project, in which 20,000,000 holes are punched into 500,000 cards continues into 1929. It is the first use of punched cards in a purely scientific application.[36]

- 1929 The Accounting and Tabulating Machine Company of Great Britain Limited renamed Powers-Samas Accounting Machine Limited (Samas, full name Societe Anonyme des Machines a Statistiques, had been the Power's sales agency in France, formed in 1922). The informal reference "Acc and Tab" would persist.[26][8]: 259 [27]

- 1930: The Remington Rand 90 column card, offering "more storage capacity [and] alphabetic capability"[8]: 50

- 1931: H.W.Egli - BULL founded to capitalize on the punched card technology patents of Fredrik Rosing Bull.[37] The Tabulator model T30 is introduced.[38]

- 1931: The Tabulating Machine Company's first punched card machine that could multiply, the 600 Multiplying Punch.[39]: 14 Their first alphabetical accounting machine - although not a complete alphabet, the Alphabetic Tabulator Model B was quickly followed by the full alphabet ATC.[8]: 50

- 1931: The term "Super Computing Machine" is used by the New York World newspaper to describe the Columbia Difference Tabulator, a one-of-a-kind special purpose tabulator-based machine made for the Columbia Statistical Bureau, a machine so massive it was nicknamed "Packard".[40][41] The Packard attracted users from across the country: "the Carnegie Foundation, Yale, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Ohio State, Harvard, California and Princeton."[42]

- 1933: Compagnie des Machines Bull is the new name of the reorganized H.W. Egli - Bull.

- 1933: The Tabulating Machine Company name disappears as subsidiary companies are merged into IBM.[43][44] The Hollerith trade name is replaced by IBM. IBM introduces removable control panels.[25]

- 1933: Dehomag's BK tabulator (developed independently of IBM) announced.[45]

- 1934: IBM renames its Tabulators as Electric Accounting Machines.[25]

- 1935: BTM Rolling Total Tabulator introduced.[25]

- 1937: Leslie Comrie establishes the Scientific Computing Service Limited - the first for-profit calculating agency.[46]

- 1937: The first collator, the IBM 077 Collator[47] The first use of an electronic component in an IBM product was a photocell in a Social Security bill-feed machine.[8]: 65 By 1937 IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day.[48]

- 1938: Powers-Samas multiplying punch introduced.[25]

- 1941 Introduction of Bull Type A unit record machines based on 80 column card.[49]

- 1943: "IBM had about 10,000 tabulators on rental [...] 601 multipliers numbered about 2000 [...] keypunch[es] 24,500".[39]: 21

- 1946: The first IBM punched card machine that could divide, the IBM 602, was introduced. Unreliable, it "was upgraded to the 602-A (a '602 that worked') [...] by 1948".[50] The IBM 603 Electronic Multiplier was introduced, "the first electronic calculator ever placed into production.".[51]

- 1948: The IBM 604 Electronic Punch. "No other calculator of comparable size or cost could match its capability".[39]: 62

- 1949: The IBM 024 Card Punch, 026 Printing Card Punch, 082 Sorter, 403 Accounting machine, 407 Accounting machine, and Card Programmed Calculator (CPC) introduced.[52]

- 1952: Bull Gamma 3 introduced.[53][54] An electronic calculator with delay-line memory, programmed by a connection panel, that was connected to a tabulator or card reader-punch. The Gamma 3 had greater capacity, greater speed, and lower rentals than competitive products.[39]: 461–474

- 1952: Remington Rand 409 Calculator (aka. UNIVAC 60, UNIVC 120) introduced.

- 1952: Underwood Corp acquires the American assets of Powers-Samas.[55][56]

By the 1950s punched cards and unit record machines had become ubiquitous in academia, industry and government. The warning often printed on cards that were to be individually handled, "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate", coined by Charles A. Philips, became a motto for the post-World War II era (even though many people had no idea what spindle meant).[57]

With the development of computers punched cards found new uses as their principal input media. Punched cards were used not only for data, but for a new application - computer programs, see: Computer programming in the punched card era. Unit record machines therefore remained in computer installations in a supporting role for keypunching, reproducing card decks, and printing.

- 1955: IBM produces 72.5 million punched cards per day.[24]

- 1957: The IBM 608, a transistor version of the 1948 IBM 604. First commercial all-transistor calculator.[39]: 34 [58]

- 1958: The "Series 50", basic accounting machines, was announced.[59] These were modified machines, with reduced speed and/or function, offered for rental at reduced rates. The name "Series 50" relates to a similar marketing effort, the "Model 50", seen in the IBM 1940 product booklet.[60] An alternate report identifies the modified machines as "Type 5050" introduced in 1959 and notes that Remington-Rand introduced similar products.[61]

- 1959: BTM is merged with rival Powers-Samas to form International Computers and Tabulators(ICT).

- 1959: The IBM 1401, internally known in IBM for a time as "SPACE" for "Stored Program Accounting and Calculating Equipment" and developed in part as a response to the Bull Gamma 3, outperforms three IBM 407s and a 604, while having a much lower rental.[39]: 465–494 That functionality combined with the availability of tape drives, accelerated the decline in unit record equipment usage.[62]

- 1960: The IBM 609 Calculator, an improved 608 with core memory. This will be IBMs last punched card calculator.[63]

Many organizations were loath to alter systems that were working, so production unit record installations remained in operation long after computers offered faster and more cost effective solutions. Cost or availability of equipment was another factor; for example in 1965 an IBM 1620 computer did not have a printer as standard equipment, so it was normal in such installations to punch output onto cards and then print these cards on an IBM 407 accounting machine. Specialized uses of punched cards such as toll collection, microform aperture cards, and punched card voting kept unit record equipment in use into the twenty-first century.

- 1968: International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) is merged with English Electric Computers, forming International Computers Limited (ICL).

- 1969: The IBM System/3, renting for less than $1,000 a month, the ancestor of IBM's midrange computer product line, aka. minicomputers, was aimed at new customers and organizations that still used IBM 1400 series computers or unit record equipment. It featured a new, smaller, punched card with a 96 column format. Instead of the rectangular punches in the classic IBM card, the new cards had tiny (1 mm), circular holes much like paper tape. By July 1974 more than 25,000 System/3s had been installed.[64]

- 1971: The IBM 129 Card Data Recorder (keypunch and auxiliary on-line card reader/punch) is the last, or among the last, 80-column card unit record product announcements (other than card readers and card punches attached to computers).

- 1975 Cardamation founded, a U.S. company that supplied punched card equipment and supplies until 2011.[65]

Endings

[edit]- 1976: The IBM 407 Accounting Machine was withdrawn from marketing.[66]

- 1978: IBM's Rochester plant made its last shipment of the IBM 082, 084, 085, 087, 514, and 548 machines.[67] The System/3 was succeeded by the System/38.[64]

- 1980: The last reconditioning of an IBM 519 Document Originating Punch.[68]

- 1984: The IBM 029 Card Punch, announced in 1964, was withdrawn from marketing.[69] IBM closed its last punch card manufacturing plant.[70]

- 2010: A group from the Computer History Museum reported that an IBM 402 Accounting Machine and related punched card equipment was still in operation at a filter manufacturing company in Conroe, Texas.[71] The punched card system was still in use as of 2013.[72]

- 2011: The owner of Cardamation, Robert G. Swartz, dies, and the company, perhaps the last supplier of punch card equipment, ceases operation.[73][74]

- 2015: Punched cards for time clocks and some other applications were still available; one supplier was the California Tab Card Company.[75] As of 2018, the web site was no longer in service.

Punched cards

[edit]The basic unit of data storage was the punched card. The IBM 80-column card was introduced in 1928. The Remington Rand Card with 45 columns in each of two tiers, thus 90 columns, in 1930.[76] Powers-Samas punched cards include one with 130 columns.[77] Columns on different punch cards vary from 5 to 12 punch positions.

The method used to store data on punched cards is vendor specific. In general each column represents a single digit, letter or special character. Sequential card columns allocated for a specific use, such as names, addresses, multi-digit numbers, etc., are known as a field. An employee number might occupy 5 columns; hourly pay rate, 3 columns; hours worked in a given week, 2 columns; department number 3 columns; project charge code 6 columns and so on.

Keypunching

[edit]

Original data were usually punched into cards by workers, often women, known as keypunch operators, under the control of a program card (called a drum card because it was installed on a rotating drum in the machine), which could automatically skip or duplicate predefined card columns, enforce numeric-only entry, and, later, right-justify a number entered.

Their work was often checked by a second operator using a verifier machine, also under the control of a drum card. The verifier operator re-keyed the source data and the machine compared what was keyed to what had been punched on the original card.

Sorting

[edit]

An activity in many unit record shops was sorting card decks into the order necessary for the next processing step. Sorters, like the IBM 80 series Card Sorters, sorted input cards into one of 13 pockets depending on the holes punched in a selected column and the sorter's settings. The 13th pocket was for blanks and rejects. Cards were sorted on one card column at a time; sorting on, for example, a five digit zip code required that the card deck be processed five times. Sorting an input card deck into ascending sequence on a multiple column field, such as an employee number, was done by a radix sort, bucket sort, or a combination of the two methods.

Sorters were also used to separate decks of interspersed master and detail cards, either by a significant hole punch or by the cards corner-cut.[78]

More advanced functionality was available in the IBM 101 Electronic Statistical Machine, which could

- Sort

- Count

- Accumulate totals

- Print summaries

- Send calculated results (counts and totals) to an attached IBM 524 Duplicating Summary Punch.[79]: pp. 5–6

Tabulating

[edit]

Reports and summary data were generated by accounting or tabulating machines. The original tabulators only counted the presence of a hole at a location on a card. Simple logic, like ands and ors could be done using relays.

Later tabulators, such as those in IBM's 300 series, directed by a control panel, could do both addition and subtraction of selected fields to one or more counters and print each card on its own line. At some signal, say a following card with a different customer number, totals could be printed for the just completed customer number. Tabulators became complex: the IBM 405 contained 55,000 parts (2,400 different) and 75 miles of wire; a Remington Rand machine circa 1941 contained 40,000 parts.[23][80]

Calculating

[edit]In 1931, IBM introduced the model 600 multiplying punch. The ability to divide became commercially available after World War II. The earliest of these calculating punches were electromechanical. Later models employed vacuum tube logic. Electronic modules developed for these units were used in early computers, such as the IBM 650. The Bull Gamma 3 calculator could be attached to tabulating machines, unlike the stand-alone IBM calculators.[54]

Card punching

[edit]

Card punching operations included:

- Gang punching - producing a large number of identically punched cards—for example, for inventory tickets.

- Reproducing - reproducing a card deck in its entirety or just selected fields. A payroll master card deck might be reproduced at the end of a pay period with the hours worked and net pay fields blank and ready for the next pay period's data. Programs in the form of card decks were reproduced for backup.

- Summary punching - punching new cards with details and totals from an attached tabulating machine.

- Mark sense reading - detecting electrographic lead pencil marks on ovals printed on the card and punching the corresponding data values into the card.[81]

Singularly or in combination, these operations were provided in a variety of machines. The IBM 519 Document-Originating Machine could perform all of the above operations.

The IBM 549 Ticket Converter read data from Kimball tags, copying that data to punched cards.

With the development of computers, punched cards were also produced by computer output devices.

Collating

[edit]IBM collators had two input hoppers and four output pockets. These machines could merge or match card decks based on the control panel's wiring as illustrated here.

The Remington Rand Interfiling Reproducing Punch Type 310-1 was designed to merge two separate files into a single file. It could also punch additional information into those cards and select desired cards.[76]

Collators performed operations comparable to a database join.

Interpreting

[edit]

An interpreter prints characters on a punched card equivalent to the values of all or selected columns. The columns to be printed can be selected and even reordered, based on the machine's control panel wiring. Later models could print on one of several rows on the card. Unlike keypunches, which print values directly above each column, interpreters generally use a font that was a little wider than a column and can only print up to 60 characters per row.[82] Typical models include the IBM 550 Numeric Interpreter, the IBM 557 Alphabetic Interpreter, and the Remington Rand Type 312 Alphabetic Interpreter.[76]

Filing

[edit]Batches of punched cards were often stored in tub files, where individual cards could be pulled to meet the requirements of a particular application.

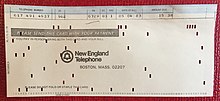

Transmission of punched card data

[edit]Electrical transmission of punched card data was invented in the early 1930s. The device was called an Electrical Remote Control of Office Machines and was assigned to IBM. Inventors were Joseph C. Bolt of Boston & Curt I. Johnson; Worcester, Mass. assors to the Tabulating Machine Co., Endicott, NY. The Distance Control Device received a US patent in Aug.9,1932: U.S. patent 1,870,230. Letters from IBM talk about filling in Canada in 9/15/1931.

Processing punched tape

[edit]The IBM 046 Tape-to-Card Punch and the IBM 047 Tape-to-Card Printing Punch (which was almost identical, but with the addition of a printing mechanism) read data from punched paper tape and punched that data into cards. The IBM 063 Card-Controlled Tape Punch read punched cards, punching that data into paper tape.[83]

Control panel wiring and Connection boxes

[edit]

The operation of Hollerith/BTM/IBM/Bull tabulators and many other types of unit record equipment was directed by a control panel.[85] Operation of Powers-Samas/Remington Rand unit record equipment was directed by a connection box.[86]

Control panels had a rectangular array of holes called hubs which were organized into groups. Wires with metal ferrules at each end were placed in the hubs to make connections. The output from some card column positions might connected to a tabulating machine's counter, for example. A shop would typically have separate control panels for each task a machine was used for.

Paper handling equipment

[edit]

For many applications, the volume of fan-fold paper produced by tabulators required other machines, not considered to be unit record machines, to ease paper handling.

- A decollator separated multi-part fan-fold paper into individual stacks of one-part fan-fold and removed the carbon paper.

- A burster separated one-part fan-fold paper into individual sheets. For some uses it was desirable to remove the tractor-feed holes on either side of the fan-fold paper. In these cases the form's edge strips were perforated and the burster removed them as well.

See also

[edit]- British Tabulating Machine Company

- Fredrik Rosing Bull

- Gustav Tauschek

- IBM Electromatic Table Printing Machine

- IBM 632 Accounting Machine

- IBM 6400 Series

- Leslie Comrie

- List of IBM products

- Powers Accounting Machine Company

- Powers-Samas

- Remington Rand

- Wallace John Eckert

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Origin of the term unit record: It was in 1888 that Mr. Davidson conceived the idea... The idea was that the card catalog, then in fairly general use by libraries, could be adapted with advantage to certain 'commercial indexes'. ... Directly connected with these is one of the most important principles of all - the 'unit record' principal in business. Hitherto, the records of a business house had been kept, each for one fixed purpose, and their usefulness had been restricted by the inflexible limitations of a bound book. The unit record principle, made possible by the card system, gave to these records a new accessibility and significance. ... The Story of the Library Bureau. Cowen Company, Boston. 1909. p. 50.

- ^ By 1887 ...Doctor Herman Hollerith had worked out the basis for a mechanical system of recording, compiling and tabulating census facts... Each card was used to record the facts about an individual or a family - a unit situation. These cards were the forerunners of today's punched cards or unit records. General Information Manual: An Introduction to IBM Punched Card Data Processing. IBM. p. 1.

- ^ Data processing equipment can be divided into two basic types - computers and unit record machines. Unit Record derives form the common use of punchcards to carry information on a one-item-per-card basis, which makes them unit records. Janda, Kenneth (1965). Data Processing. Northwestern University Press. p. 47.

- ^ Like the index card, the punched card is a unit record containing one kind of data, which can be combined with other kinds of data punched in other cards. McGill, Donald A.C. (1962). Punched Cards, Data Processing for Profit Improvement. McGraw-Hill. p. 29.

- ^ International Business Machines Corp. (1957). Machine Functions (PDF). 224-8208-3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ International Business Machines Corp. (1959). Flow Charting and Block Diagramming Techniques (PDF). /C20-8008-0.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Cemach, Harry P., 1951, The Elements of Punched Card Accounting, Pitman, p.27. Within certain limits the information punched in any column of a card can be reproduced in any desired position by the tabulator. This is achieved by means of a Connection Box. ... The connection box can be easily removed from the tabulator and replaced by another.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pugh, Emerson W. (March 16, 1995). Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262161473.

- ^ Columbia University Computing History - Herman Hollerith

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau: The Hollerith Machine

- ^ An early use of "Hollerith Card" can be found in the 1914 Actuarial Soc of America Trans. v.XV.51,52- Perforated Card System

- ^ Truesdell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census 1890-1940. US GPO.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau: Tabulation and Processing

- ^ a b A History of Sperry Rand Corporation (4th ed.). Sperry Rand. 1967. p. 32.

- ^ a b Austrian, Geoffrey D. (1982). Herman Hollerith: Forgotten Giant of Information Processing. Columbia University Press. pp. 41, 178–179. ISBN 0-231-05146-8.

- ^ a b Truesdell, Leon Edgar (1965). The development of punch card tabulation in the Bureau of the Census, 1890-1940: with outlines of actual tabulation programs. U.S. G.P.O. pp. 84–86.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Hollerith Automatic Horizontal Sorter". 23 January 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2005.

- ^ Austrian, 1982, p.216

- ^ Computing at Columbia: Timeline - Early

- ^ Durand, Hon. E. Dana (September 23–28, 1912). Tabulation by Mechanical Means - Their Advantages and Limitations, volume VI. Transactions of the Fifteenth International Congress on Hygiene and Demography.

- ^ Cortada, James W. (February 8, 1993). Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, & Remington Rand & The Industry they Created 1865—1956. Princeton University Press. pp. 56–59. ISBN 978-0691048079.

- ^ Cemach, Harry P. (1951). The Elements of Punched Card Accounting. Pitman. p. 5.

- ^ a b c Know-How Makes Them Great. Remington Rand. 1941.

- ^ a b IBM Archives: Endicott chronology, 1951-1959

- ^ a b c d e f g h Information Technology Industry TimeLine

- ^ a b Cortada p.57

- ^ a b Van Ness, Robert G. (1962). Principles of Punched Card Data Processing. The Business Press. p. 15.

- ^ Punched Hole Accounting. IBM. 1924. p. 18.

- ^ Engelbourg p.173

- ^ "IBM Archives: 1920". IBM. 23 January 2003. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

- ^ Rojas, Raul, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of Computers and Computer History. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 656.

- ^ Aspray, William, ed. (1990). Computing Before Computers. Iowa State University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-8138-0047-1.

- ^ IBM Type 80 Electric Punched Card Sorting Machine

- ^ IBM 301 Accounting Machine (the Type IV)

- ^ Columbia University Professor Ben Wood

- ^ The Origins of Cybersace. Christie's. 2005. p. 14.

- ^ Heide, Lars (2002) National Capital in the Emergence of a Challenger to IBM in France Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ H.W.Egli - BULL Tabulator model T30 Archived May 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Bashe, Charles J.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H.; Pugh, Emerson W. (1986). IBM's Early Computers. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-02225-7.

- ^ Eames, Charles; Eames, Ray (1973). A Computer Perspective. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 95. The date given, 1920, should be 1931 (see the Columbia Difference Tabulator web site)

- ^ Columbia Difference Tabulator

- ^ Columbia Alumni News, Vol.XXIII, No.11, December 11, 1931, p.1

- ^ New York Times, July 15, 1933, All subsidiaries of the International Business Machines Corporation in this county have been merged with the parent company to obtain efficient operation.

- ^ William Rodgers (1969). THINK: A Biography of the Watsons and IBM. p. 83. ISBN 9780297000235.

- ^ Rojas, Raul; Hashagen, Ulf (2000). The First Computers. MIT.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin & Aspray, William (2004). COMPUTER A History of the Information Machine. Westview. p. 59.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The world's first for-profit calculating agency. - ^ IBM 077 Collator

- ^ IBM Archive: Endicott card manufacturing

- ^ Equipements à cartes perforées (Punched cards machines) type A (GR) 1941-1950 Archived August 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The IBM 602 Calculating Punch

- ^ IBM 603 Electronic Multiplier

- ^ IBM Archives: Endicott chronology 1941-1949

- ^ Bull Gamma 3 1952-1960 Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Bull Gamma 3

- ^ Computer History Museum: Underwood Corporation

- ^ An Underwood-Samas sorter

- ^ Lee, J.A.L. (1995) Computer Pioneers, IEEE, p.557

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H. (1991). IBM's 360 and early 370 systems. MIT Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-262-16123-0.

- ^ IBM Archives - DPD chronology

- ^ "IBM 1940 products brochure" (PDF).

- ^ Van Ness, Robert G. (1962). Principles of Punched Card Data Processing. Business Press. p. 10.

- ^ IBM Corporation (1959). IBM 1401 Data Processing System: From Control Panel to Stored Program (PDF). Order number F20-208.

- ^ Columbia University: The IBM 609 Calculator

- ^ a b IBM System 3

- ^ Dyson, George (1999) The Undead (Cardamation), Wired v.7.03

- ^ IBM 407 Accounting Machine

- ^ IBM Rochester chronology, page3

- ^ IBM Rochester chronology

- ^ IBM 029 Card Punch

- ^ IBM Punch-Card Plant Will Close, Joseph Perkins, The Washington Post, July 2, 1984

- ^ Visit to a working IBM 402 in Conroe, Texas

- ^ Conroe company still using computers museums want to put on display By Craig Hlavaty, Houston Chronicle, April 24, 2013

- ^ "Robert G. Swartz". legacy.com. December 19, 2011.

- ^ "Cardamation". ibm-main (Mailing list).

- ^ "California Tab Card Company". Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ a b c Gillespie, Cecil (1951). Accounting Systems: Procedures and Methods, Chapter 34: Equipment for Punched Card Accounting. Cowen Company, Boston. pp. 684–704.

- ^ (Cemach, 1951, pp 47-51)

- ^ Reference Manual, IBM 82, 83, and 84 Sorters. 1962. p. 25.

- ^ IBM 101 Electronic Statistical Machine - Reference Manal (PDF).

- ^ Cambell-Kelly, Martin; Aspray, William (2004). Computer: a history of the information machine (2 ed.). Basic Books. p. 42.

- ^ IBM (1949). The How and Why of IBM Mark Sensing (PDF). 52-5862-0. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- ^ IBM Card Interpreters

- ^ IBM (1958). IBM 063 Card-Controlled Tape Punch (PDF). 224-5997-3.

- ^ IBM (1963). IBM Accounting Machine: 402, 403 and 419 Principles of Operation (PDF). 224-1614-13.

- ^ IBM (1956). IBM Reference Manual: Functional Wiring Principles (PDF). 22-6275-0.

- ^ Sutton, O. (1943). Machine Accounting for Small or Large Business. Macdonald & Evans. pp. 173–178.

Further reading

[edit]Note: Most IBM form numbers end with an edition number, a hyphen followed by one or two digits.

For Hollerith and Hollerith's early machines see: Herman Hollerith#Further reading

- Histories

- Aspray, William, ed. (1990). Computing before Computers. Iowa State University Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-8138-0047-1.

- Brennan, Jean Ford (1971). The IBM Watson Laboratory at Columbia University: A History. IBM. p. 68.

- Cortada, James W. (1983). An Annotated Bibliography on the History of Data Processing. Greenwood. p. 215. ISBN 0-313-24001-9.

- Cortada, James W. (1993). Before the Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, & Remington Rand & the Industry they created, 1865 - 1956. Princeton. p. 344. ISBN 0-691-04807-X.

- Engelbourg, Saul (1954). International Business Machines: A Business History (Ph.D.). Columbia University. p. 385. Reprinted by Arno Press, 1976, from the best available copy. Some text is illegible.

- Krawitz, Miss Eleanor (November 1949). "Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory: A Center for Scientific Research Using Calculating Machines". Columbia Engineering Quarterly.

- Lars, Heide (2009). Punched-Card Systems and the Early Information Explosion, 1880--1945. Johns Hopkins U Press. pp. 369. ISBN 978-0-8018-9143-4.

- Pugh, Emerson W.; Heide, Lars. IEEE STARS: Early Punched Card Equipment, 1880-1951. IEEE.

- Randell, Brian (1982). The Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers (3 ed.). Springer-Verlag. p. 580. ISBN 0-387-11319-3. includes Hollerith (1889) reprint

- Punched card applications

- Baehne, G.W., ed. (1935). Practical Applications of the Punched Card Method in Colleges and Universities. Columbia University. p. 442. – With 42 contributors and articles ranging from Analysis of College Test Results to Uses of the Automatic Multiplying Punch this is book provides an extensive view of unit record equipment use over a wide range of applications. For details of this book see The Baehne Book..

- Linnekin, Leroy Corliss (1938). The Scope of Punched Card Accounting. Boston University, College of Business Administration - Thesis. pp. 314 + Appendix. The appendix has IBM and Powers provided product detail sheets, with photo and text, for many machines.

- Ferris, Lorna; et al. (1948). Bibliography on the Uses of Punched Cards. MIT.

- Grosch, Herb (1945). Bibliography on the Use of IBM Machines in Scientific Research, Statistics, and Education. IBM. (source: Frank da Cruz (Feb 6, 2010). "Herb Grosch". Columbia University. Retrieved 14 June 2011.) There is a 1954 edition, Ann F. Beach, et al., similar title and a 1956 edition, Joyce Alsop.

- IBM (1944). IBM Accounting Course (PDF). 25-4933-3-3M-ME-1-49. Describes several punched card applications.

- Eckert, W.J. (1940). Punched Card Methods in Scientific Computation. Columbia University. p. 136. ISBN 0-262-05030-7. Note: ISBN is for a reprint ed.

- The machines

- Bureau of Naval Personnel (1971). Basic Data Processing (PDF). Dover. p. 315. ISBN 0-486-20229-1. Unabridged edition of "Data Processing Tech 3 &2", aka. "Rate Training manual NAVPERS 10264-B", 3rd revised ed. 1970

- Brooks, Frederick P. Jr.; Iverson, Kenneth E. (1963). Automatic Data Processing. Wiley. p. 494. Chapter 3 Punched Card Equipment describes American machines with some details of their logical organization and examples of control panel wiring.

- Cemach, Harry P. (1951). The Elements of Punched Card Accounting. Pitman. p. 137. The four main systems in current use - Powers-Samas, Hollerith, Findex, and Paramount - are examined and the fundamentals principles of each are fully explained.

- Fierheller, George A. (2014). Do not fold, spindle or mutilate: the 'hole' story of punched cards. Stewart Pub. ISBN 978-1-894183-86-4. Retrieved June 19, 2013. An accessible book of recollections (sometimes with errors), with photographs and descriptions of many unit record machines. The ISBN is for an earlier (2006), printed, edition.

- Friedman, Burton Dean (1955). Punched Card Primer. American Book - Stratford Press. This elementary introduction to punched card systems is unusual because unlike most others, it not only deals with the IBM systems but also illustrates the card formats and equipment offered by Remington Rand and Underwood Samas. Erwin Tomash Library

- IBM (1936) Machine Methods of Accounting, 360 p. Includes a 12-page 1936 IBM-written history of IBM and descriptions of many machines.

- IBM (1940). IBM products brochure (PDF).

- IBM. An Introduction to IBM Punched Card Data Processing (PDF). F20-0074.

- IBM (1955–56). IBM Sales Manual (unit record equipment pages only).

- IBM (1957). Machine Functions (PDF). 224-8208-3. A simplified description of common IBM machines and their uses.

- IBM (1957). IBM Equipment Summary (PDF). With descriptions, photos and rental prices.

- IBM (1959). IBM Operators Guide: Reference Manual (PDF). A24-1010-0. The IBM Operators Guide, 22-8485 was an earlier edition of this book

- Murray, Francis J. (1961). Mathematical Machines Volume 1: Digital Computers. Columbia University Press. Has extensive descriptions of unit record machine construction.

- Ken Shirriff's blog Inside card sorters: 1920s data processing with punched cards and relays.

External links

[edit]- Columbia University Computing History IBM Tabulators and Accounting Machines IBM Calculators IBM Card Interpreters IBM Reproducing and Summary Punches IBM Collators

- Columbia University Computing History: L.J. Comrie From that site Comrie was the first to turn punched-card equipment to scientific use

- History of Bull Extracted and translated from Science et Vie Micro magazine, No. 74, July–August, 1990: The very international history of a French giant

- Musée virtuel de Bull et de l'informatique Française: Information Technology Industry TimeLine From that site The present TimeLine page differs from similar pages available on the Internet because it is focused more on the industry than on "inventions". It was originally designed to show the place of the European and more specifically the French computer industry facing its world-wide competition. Most of published time-line charts either consider that everything had an American origin or they show their country patriotism (French, Italian, Russian or British) or their company patriotism.

- Musée virtuel de Bull et de l'informatique Française (Virtual Museum of French computers) Systems Catalog

- Early office museum

- IBM Archives

- IBM Punch Card Systems in the U.S. Army

- IBM early Card Reader and 1949 electronic Calculator video of unit record equipment in museum

- Working Tabulating machines and punched card equipment in technikum29 Computermuseum (nr. Frankfurt/Main, Germany)