Electoral reform

| Part of the Politics series |

| Elections |

|---|

|

|

|

Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems which alters how public desires are expressed in election results.

Description

[edit]Reforms can include changes to:

- Voting systems, such as adoption of proportional representation, Single transferable voting,a two-round system (runoff voting), instant-runoff voting (alternative voting, ranked-choice voting, or preferential voting), Instant Round Robin Voting called Condorcet Voting, range voting, approval voting, citizen initiatives and referendums and recall elections.

- Vote-counting procedures

- Rules about political parties, typically changes to election laws

- Eligibility to vote (including widening of the vote, enfranchisement and extension of suffrage to those of certain age, gender or race/ethnicity previously excluded)

- How candidates and political parties are able to stand (nomination rules) and how they are able to get their names onto ballots (ballot access)

- Electoral constituencies and election district borders. This can include consideration of multiple-member districts as opposed to single-member districts. District magnitude is measure of number of seats per district.

- Ballot design and voting equipment. Preferential ballots as used in single transferable voting necessitate different ballot design compared to X voting under first-past-the-post voting and some other systems.

- Scrutineering (election monitoring by candidates, political parties, etc.)

- Safety of voters and election workers

- Measures against bribery, coercion, and conflicts of interest

- Financing of candidates' and referendum campaigns

- Factors which affect the rate of voter participation (voter turnout)

Electoral reforms can contribute to democratic backsliding or may be advances toward wider and deeper democracy.

Nation-building

[edit]In less democratic countries, elections are often demanded by dissidents; therefore the most basic electoral-reform project in such countries is to achieve a transfer of power to a democratically elected government with a minimum of bloodshed, e.g. in South Africa in 1994. Such power transfers can be complex. Such projects tend to require changes to national or other constitutions and to alter balances of power. Electoral reforms are often politically painful. Authorities may try to postpone reforms as long as possible but at risk of social unrest with potential of rebellion, political violence and/or civil war.

Role of United Nations

[edit]The United Nations Fair Elections Commission provides international observers to national elections that are likely to face challenges by the international community of nations, e.g., in 2001 in Yugoslavia, in 2002 in Zimbabwe.

The United Nations standards address safety of citizens, coercion, scrutiny, and eligibility to vote. They do not impose ballot styles, party diversity, or borders on electoral constituencies. Various global political movements, e.g., labour movements, the Green party, Islamism, Zionism, advocate various cultural, social, ecological means of setting borders that they consider "objective" or "blessed" in some other way. Contention over electoral constituency borders within or between nations and definitions of "refugee", "citizen", and "right of return" mark various global conflicts, including those in Israel/Palestine, the Congo, and Rwanda.

Electoral boundaries

[edit]Electoral constituencies (or "ridings" or "districts") need to be adjusted frequently, or by statutory rules and definitions, to eliminate malapportionment due to population movements. In some systems this is done by moving the boundaries to take in more or fewer residents; in other systems, districts stay as they are and when necessary the number of members in the district is increased or decreased. (Multi-member districts are allowed under the U.S. constitution.)[1]

Multi-member districts are a component of many proportional representation systems.

Where multi-member districts are used, the number of seats in a district (not the districts' boundaries) may be altered. This satisfies one of the reasons to change electoral district boundaries: to ensure that the ratio between the number of voters (or population) and each of the members in the district is the same across districts.

The use of districts of different district magnitudes, with varying numbers of seats in each district perhaps ranging from one to ten or more, allows representation of electoral districts to be changed to be broadly proportional to the number of voters while retaining pre-existing districts, such as city corporate limits, counties or even provinces or states.[2]

The lack [clarification needed] of respect for "natural" boundaries (municipalities or community or infrastructure or natural areas) is a noted disadvantage of the single-member districts that are necessary for first-past-the-post voting. The lack of "natural" boundaries also appears in some criticisms of proposed reforms, such as the Jenkins Commission's proposal of alternative vote plus system for the United Kingdom, because of its use of artificial single-member districts.

Some electoral reforms seek to have district boundaries match pre-existing jurisdictions or cultural or ecological criteria (with the number of district members adjusted, when necessary, to reflect population changes).Bioregional democracy sets boundaries to fit exactly with ecoregions to seek to improve the management of commonly-owned property and natural resources. Fixing districts in place is a way to avoid gerrymandering, in which constituency boundaries are set deliberately to favor one party over another.

Electoral boundaries and their manipulation have been a major issue in the United States, in particular. Due to beliefs that politics or laws prevent deeper electoral reform,[clarification needed] such as multiple-member districts or proportional representation, "affirmative gerrymandering" has been used to create districts in which a previously-disenfranchised minority group, such as blacks, is in the majority and thus elects a representative of that group.

By country

[edit]Albania

[edit]In 2020, a 1 percent electoral threshold was set and the election campaign financing law was reformed in Albania.[3][4]

Australia

[edit]The Proportional Representation Society of Australia advocates the single transferable vote and proportional representation.

STV is currently used to elect the upper house at the national level and in four states, and the lower house in two states. [5]

Canada

[edit]Several national and provincial organizations promote electoral reform, especially by advocating more party-proportional representation, as most regions of Canada have at least three competitive political parties (some four or five) and the traditional first-past-the-post election system operates best where just two parties are competing.

Furthermore, Election Districts Voting advocates proportional representation electoral reforms that enable large majorities of voters to directly elect party candidates of choice, not just parties of choice.[6]

Also, a large non-party organization advocating electoral reform nationally is Fair Vote Canada but there are other advocacy groups. One such group is The Equal Vote Coalition who has organized a multi-year research campaign involving many of the world experts on electoral reform.

Several referendums to decide whether or not to adopt such reform have been held at the provincial level in the last two decades; none has thus far resulted in a change from the plurality system currently in force. (In the past and as recently as the 1990s, all provinces and even the federal government have reformed their electoral systems but so far none of those changes have followed a referendum, with the sole exception being extension of the franchise to (some) women in British Columbia in 1916).[7] Reforms of the past without referendums initiated the partial use of proportional representation (single transferable voting) in the provinces of Manitoba and Alberta. Controversially, the referendum threshold for adoption of a new voting system has regularly been set at a "supermajority": for example, 60 percent of ballots cast approving the proposed system in order for the change to be implemented. In most provincial referendums the change side was roundly defeated, gaining less than 40 percent support in most cases. But in two cases, a majority of voters voted for change.

In 2005, a majority of votes cast in an electoral reform referendum held in British Columbia were cast in favour of change to STV.[8]

In the November 7, 2016, electoral reform plebiscite on Prince Edward Island, the government declined to specify in advance how it would use the results. Mixed member proportional Representation won the five-option instant-runoff voting contest, taking 52 percent of the final vote versus 42 percent for first-past-the-post, but the PEI government did not commit to implementing a proportional voting system, citing the turnout of 36 percent as making it "doubtful whether these results can be said to constitute a clear expression of the will of Prince Edward Islanders". PEI regularly sees turnout above 80 percent in most elections.[9]

Seven provincial level referendums on electoral reform have been held to date:

- 2005 British Columbia electoral reform referendum

- 2005 Prince Edward Island electoral reform referendum

- 2007 Ontario electoral reform referendum

- 2009 British Columbia electoral reform referendum

- 2016 Prince Edward Island electoral reform referendum

- 2018 British Columbia electoral reform referendum

- 2019 Prince Edward Island electoral reform referendum

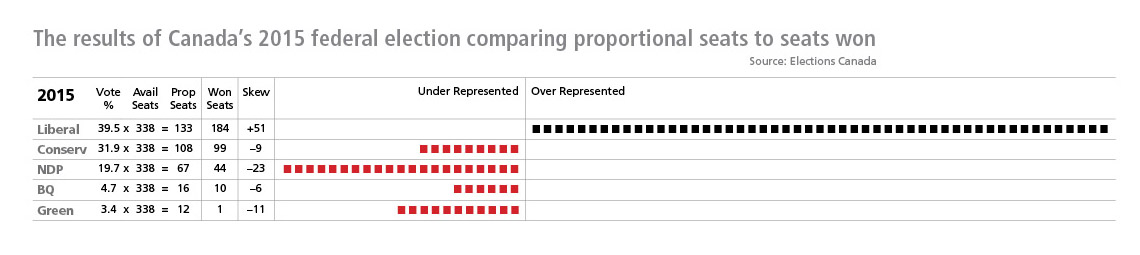

During the 2015 federal election all three opposition parties promised some measure of electoral reform before the next federal election. The NDP promised to implement mixed-member proportional representation with regional and open party lists, based on the 2004 recommendations of the Law Commission,[10] and the Liberals simply promised to form an all-party committee to investigate various electoral reform options "including proportional representation, ranked ballots, mandatory voting and online voting."[11] The Liberal leader, who is now prime minister, Justin Trudeau, is believed to prefer a winner-take-all, preferential voting system known as Instant Runoff Voting; however, there are many prominent members of his caucus and cabinet who openly support proportional representation (Stephane Dion, Dominic Leblanc, Chrystia Freeland, and others).[10] In 2012, Dion authored an editorial for the National Post advocating his variation of proportional representation by the single transferable vote dubbed "P3" (proportional, preferential and personalized).[12] Regardless, Trudeau has promised to approach the issue with an open mind. Conservative interim leader, Rona Ambrose, has indicated a willingness to investigate electoral reform options, but her party's emphatic position is that any reform must first be approved by the voters in a referendum. The Liberal government's position is that a referendum is unnecessary as they clearly campaigned on making "2015 Canada's last First Past the Post election." The Green Party of Canada has always been supportive of proportional representation. At the party's Special General Meeting in Calgary on December 5, 2016, Green Party members passed a resolution endorsing Mixed Member Proportional Representation as its preferred model, while maintaining an openness to any proportional voting system producing an outcome with a score of 5 or less on the Gallagher Index.[13]

The Liberal members of the special all-committee[clarification needed] on electoral reform urged Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to break his promise to change Canada's voting system before the next federal election in 2019. That call for inaction came as opposition members of the committee pressured Trudeau to keep the commitment. In its final report, Strengthening Democracy in Canada, the Standing Committee on Electoral Reform recommended the government design a new proportional system and hold a national referendum to gauge Canadians' support.[14]

Between December 2016 and January 2017, the Government of Canada undertook a survey of Canadian opinion regarding electoral reform, with some 360,000 responses received.[citation needed]

On February 1, 2017, the Liberal Minister of Democratic Institutions, Karina Gould, announced that a change of voting system would no longer be in her mandate, citing a lack of broad consensus among Canadians on what voting system would be best.[15]

The Province of Ontario permitted the use of instant runoff voting, often called the "ranked ballot", for municipal elections.[16] IRV is not a proportional voting system and is opposed by both Election Districts Voting[17] and Fair Vote Canada for provincial or federal elections.[18]

Czech Republic

[edit]The electoral threshold for multi-party coalitions was reduced due to a court ruling from 10 percent to 8 percent for two-party coalitions in 2021.[19]

Denmark

[edit]The Danish electoral system was reformed from first-past-the-post voting to additional member system in 1915 and proportional representation (a form of mixed-member proportional with list PR) used at both district level and overall at-large in 1920.[20]

European Union

[edit]An minimum electoral threshold of 3.5 percent has been proposed by the European Parliament.[21] A minimum electoral threshold is considered unconstitutional by German courts and was not applied in Germany.[22] Transnational party-lists have been proposed for the European parliament elections.[23]

Georgia

[edit]Changes to the constitution of Georgia in 2017 reformed the presidential election to an indirect election through an electoral college starting with the 2024 Georgian presidential election.[24]

Germany

[edit]In 1953 the federal state electoral threshold was replaced with a national electoral threshold, reducing party fragmentation. In 1972 the voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. In 1987, the seat allocation method was switched from the D'Hondt method to largest remainder method and was switched again in 2009, to Webster/Sainte-Laguë method, due to concerns of lower proportionality for small parties.

The 2013 the compensation mechanism was adjusted to reduce the negative vote weight in compensating between federal states.

In 2023, the German Parliament adopted a federal electoral law reform which replaced the flexible number of seats with a fixed size of 630 seats and removed the provision which allowed parties which won at least 3 single-member seats to be exempt from the 5 percent electoral threshold.[25]

Greece

[edit]In 2016, the majority bonus system was replaced with proportional representation, applying only after next election.[26] In 2020, proportional representation was replaced with the majority bonus system, applying only after next election.[27]

Hungary

[edit]In 2012, a mixed-member majoritarian voting system with a combination of parallel and positive vote transfer was introduced.[28]

India

[edit]Electoral bonds allowing anonymous contributions to political parties were introduced in 2017, and the limit on financial contributions by companies was removed.[29]

Iraq

[edit]In 2020, the proportional representation with modified Sainte-Laguë method for seat allocation was reformed to single non-transferable vote.[30][31]

Israel

[edit]There is continuous talk in Israel about "governability" ("משילות" in Hebrew). The following reforms were carried in the last three decades:

- Between 1996 and 2001, the PM was elected directly, while keeping a strong parliament. Direct election for the PM was abandoned afterwards, amid disappointment with the change. The earlier Westminster system was reinstated like it was before.

- The minimum threshold a party needs to enter parliament was gradually raised. It was 1 percent until 1988; it was then raised to 1.5 percent and remained at that level until 2003, when it was again raised to 2 percent. On March 11, 2014, the Knesset approved a new law to raise the threshold to 3.25 percent (approximately 4 seats).

- The process of throwing off an existing coalition government was slowly made harder, and now it is nearly impossible to impeach a government without triggering a new election. As of 2015, one needs to present a full new government with a majority support in order to impeach a government. This too, was done gradually between 1996 and 2014.

Italy

[edit]Italian electoral reforms include the Italian electoral law of 2017, the Italian electoral law of 2015, the Italian electoral law of 2005 and the Italian electoral law of 1993.

Lesotho

[edit]Lesotho reformed in 2002 to a mixed-member proportional representation,[32] where parties could choose to not run for either constituency seats or party-list seats. This prevented the compensatory mechanism and effectively resulted in parallel voting. Further reform in 2012 introduced mixed single-voting, forcing parties to run for both constituency seats or party-list seats and improving the proportionality.[citation needed]

Mongolia

[edit]In 2019, the electoral law for Mongolian legislative elections was changed to plurality-at-large voting.[33] The new electoral law barred people found guilty of "corrupt practices" from standing in elections, marginalized smaller parties, and effectively removed the right of Mongolian expatriates to vote, as they could not be registered in a specific constituency.[34]

New Zealand

[edit]Electoral reform in New Zealand began in 1986 with the report of the Royal Commission on the Electoral System entitled Towards A Better Democracy. The Royal Commission recommended that Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) be adopted instead of the current first-past-the-post system. After two referendums in 1992 and 1993, New Zealand adopted MMP. In 2004, some local body elections in New Zealand were elected using single transferable vote instead of the block vote.

Slovakia

[edit]The election silence period, where opinion polls are banned before elections, was extended in Slovakia in 2019 from 14 to 50 days, one of the longest blackout periods in the world.[35] The Slovak courts considered this change unconstitutional. In 2022, this blackout period was reduced to 48 hours.[36]

South Korea

[edit]South Korea reformed in 2019 from parallel voting to mixed-member proportional representation.[37] The formation of satellite parties reduced the effectiveness of this reform.[38]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan reformed 2008 from the single non-transferable vote to parallel voting.[39] A constitutional referendum was held 2022 to reduce the voting age from 20 to 18.[40][needs update]

Thailand

[edit]Thailand changed electoral systems in 2019, moving from parallel voting to a mixed-member proportional representation system with a mixed single vote.[41] Further reform in 2021 restored the parallel voting system and removed the proportional representation mechanism.[42]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom has generally used first-past-the-post (FPTP) for many years, but historically many constituencies elected two MPs, and other systems were used to elect a few of its parliament's members. Its last multi-member district at the national level was disbanded in 1948. Most members in the multi-member district were elected through block voting. Limited voting was used to elect some of its members starting in 1867. The passage of the Great Reform Bill of 1832 made the electoral system fairer by eliminating many of the rotten boroughs and burgage tenements that were represented by two members while having very few voters, and by allocating more seats to districts in relatively newer factory towns and cities.[43]

Since 1900, there have been several attempts at more reform. A 1910 Royal Commission on Electoral Systems recommended AV be adopted for the Commons.[44][45] A very limited use of single transferable voting (STV) came in the Government of Ireland Act 1914. A Speaker's Conference on electoral reform in January 1917 unanimously recommended a mix of AV and STV for elections to the House of Commons.[44] However, that July the Commons rejected STV by 32 votes in the committee stage of the Representation of the People Bill,[46] and by 1 vote substituted alternative vote (AV).[citation needed] The House of Lords then voted for STV,[47] but the Commons insisted on AV.[48] In a compromise, AV was abandoned and the Boundary Commission were asked to prepare a limited plan of STV to apply to 100 seats.[49][50] This plan was then rejected by the Commons,[50] although STV was introduced for the university constituencies and used until 1948 in some cases.[51]

On 8 April 1921, a private member's bill to introduce STV was rejected 211 votes to 112 by the Commons. A Liberal attempt to introduce an Alternative Vote Bill in March 1923 was defeated by 208 votes to 178. On 2 May 1924, another private member's bill for STV was defeated 240 votes to 146 in the Commons.[51]

In January 1931, the minority Labour government, then supported by the Liberals, introduced a Representation of the People Bill that included switching to AV. The bill passed its second reading in the Commons by 295 votes to 230 on 3 February 1931[52] and the clause introducing AV was passed at committee stage by 277 to 251.[53] (The Speaker had refused to allow discussion of STV.[54]) The bill's second reading in the Lords followed in June, with an amendment replacing AV with STV in 100 constituencies being abandoned as outside the scope of the bill.[55] An amendment was passed by 80 votes to 29 limiting AV to constituencies in boroughs with populations over 200,000.[56] The bill received its third reading in the Lords on 21 July, but the Labour government fell in August and the bill was lost.[51][57]

Following the wartime coalition government, a landslide victory for the Labour Party in 1945 began a period of two-party dominance in British electoral politics, in which the Conservatives and Labour exchanged power with almost total dominance over seats won and votes cast (See British General Elections since 1945). There existed no incentive for these parties to embrace a pluralist voting system in such a political settlement, and so neither supported it, and electoral reform ceased to be a political issue for several decades.

Late 20th century

[edit]With the rise of the SDP-Liberal Alliance following 1981's Limehouse Declaration, Britain gained a popular third-party bloc that supported significant reform of the voting and parliamentary systems. Several polls throughout the early 1980s placed the Alliance in front of Labour and the Conservatives, and nearly all had them within contention. The continuing Liberal Party had until then received minimal support at elections and little influence on government, with the brief exception of the Lib-Lab Pact in the late 1970s, but in which their influence was limited. Despite receiving roughly a quarter of the popular vote in both the 1983 and 1987 elections, however, few SDP-Liberal candidates were elected owing to FPTP requiring a plurality in each constituency and their vote being spread far more evenly geographically than the main parties. Therefore, the Conservatives, who benefited from overrepresentation of their vote and underrepresentation of the Alliance vote, won large majorities in the House of Commons during this period and reform remained off the agenda.

Elections to the European Parliament in mainland Britain used FPTP from their start in 1979 but were switched to a closed party list before the 1999 elections through the European Parliamentary Elections Act 1999[58] because the European Parliament mandated the use of proportional representation (more specifically either a party list or single transferable vote) in their elections.[59]

21st century

[edit]When Labour regained power in 1997, they had committed in their manifesto to a slew of new reformist policies relating to modernisation and democratisation of various institutions through electoral reform.[60] For general elections, they had committed to implementing the findings of the Jenkins Commission, which was set up to evaluate flaws in FPTP and propose a new electoral system that would suit the quirks of British politics. The commission reported back, including a proposal for AV+, but its findings were not embraced by the government and were never put before the House of Commons; therefore, FPTP remained in place for subsequent elections. They introduced a number of new assemblies, in London, Wales and Scotland, and opted for additional member systems of PR in all of these. They also adopted the supplementary vote system for directly elected mayors. While not specifically committing to elections by name, they had promised to abolish all hereditary peers in the House of Lords and establish a system by which representation in the Lords "more accurately reflected the proportion of votes cast at the previous election". Having faced continual pressure against any reform from the Lords themselves, the Prime Minister Tony Blair was forced to water-down his proposals and agree to a settlement with the Conservative leader in the Lords in which 92 hereditary peers would remain, along with faith-based peers, and all others would be life peers appointed by either the Prime Minister directly, or on the recommendation of an independent panel. In Scotland, a Labour / Liberal Democrat coalition in the new Scottish Parliament later introduced STV for local elections. However, such reforms encountered problems. When 7 percent of votes (over 140,000) were discounted or spoilt in the 2007 Scottish Parliamentary and local council elections, Scottish first minister Alex Salmond protested that "the decision to conduct an STV election at the same time as a first-past-the-post ballot for the Scottish Parliament was deeply mistaken".[61]

In the 2010 general election campaign, the possibility of a hung parliament and the earlier expenses scandal pushed electoral reform up the agenda, something long supported by the Liberal Democrats. There were protests in favour of electoral reform organised by Take Back Parliament.[62] The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government held a referendum on introducing AV for the Commons on 5 May 2011, which, despite commitments to review the voting system for "fair vote reforms" in the Conservative manifesto,[63] and an unequivocal backing of AV from the Labour Party in their manifesto,[64] was met by campaigning for No, and indifference with no clear or consistent party position, respectively.[65] It was comprehensively defeated.[66] The result of the referendum has had long-lasting political repercussions, being cited by later Conservative governments as proof that public opinion was decidedly against any reform of the voting system.[67] As the Conservatives continued to be in government in some form or another until 2024, electoral reform has never seriously been close to implementation post-2011.

The coalition had also committed to reforming the House of Lords into a primarily elected body, and a bill proposing elections under PR determining the majority of membership was put before the House in 2012. The bill was pulled before passage however, as while the government imposed a three-line whip on its MPs to support the measure, a large rebellion of Conservatives was developing. Matters were not helped by the Labour Party promising to vote against the measures, despite having promised to support similar such measures in the manifesto in 2010.[64] To avoid a painful and humiliating defeat, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, who had instigated the bill's passage and whose Liberal Democrat party had long-since supported the reform, was forced to back down. Clegg accused the Conservatives of breaking the coalition agreement, and Prime Minister David Cameron was said to be furious at his backbenchers for endangering the government's stability and authority. (See main article: House of Lords Reform Bill 2012)

The 2015 general election was expected to deliver a hung parliament. However, the Conservative Party won a narrow majority, winning 51 percent of the seats on 37 percent of the national vote, but the Green Party, UKIP and the Liberal Democrats were under-represented and the Scottish National Party over-represented in the results compared to a proportional system.[68] As a result, both during the campaign and after, there were various calls for electoral reform.[69] Nigel Farage, leader of UKIP, declared support for AV+.[70] Baron O'Donnell, the Cabinet Secretary from 2005 to 2011, argued that FPTP is not fit for purpose given the move towards multi-party politics seen in the country.[71] Journalist Jeremy Paxman also supported a move away from FPTP.[72]

In 2016, it was reported that in a conversation with a Labour peer in 1997, the Queen had expressed her opposition to changing the voting system to proportional representation.[73]

In 2021 home secretary Priti Patel proposed replacing the supplementary vote method used in some elections in England and Wales with FPTP. The posts affected were the Mayor of London, elected mayors in nine combined authorities in England, and police and crime commissioners in England and Wales.[74] In the Queen's Speech of May that year, the Government proposed the introduction of compulsory Photo ID for voters in England and in UK-wide elections.[75] These measures were implemented with the Elections Act 2022.

A number of groups in the United Kingdom are campaigning for electoral reform including the Electoral Reform Society (ERS), Make Votes Matter, Make Votes Count Coalition, Fairshare, and the Labour Campaign for Electoral Reform. In the lead up to, and especially since the 2019 general election, various anti-Brexit pressure groups and online political influencers have moved to a position supporting and calling for widespread tactical voting to bring about more favourable election results under FPTP to those parties that support reform, most notably Best for Britain.[76] In its most comprehensive form, such proposals include a national roll-out of the Unite to Remain pact in 2019, in which the Liberal Democrats, Greens, and Plaid Cymru stood down in some constituencies and endorsed each other for election, but on a much wider scale and including the Labour Party, with the expressed aim of building a rainbow coalition that could enact PR in a new parliament.[77] Their campaign for soft-left cooperation is ongoing and have primarily focused on social media initiatives and sponsoring research into voting patterns.[78] While the idea of a progressive alliance has seen significant discourse in left-leaning spaces, particularly on Twitter,[79] it is thought unlikely to ever happen. The Labour Party does not support electoral reform and has a clause in their constitution (section 5, clause IV) requiring them to stand candidates in every parliamentary seat bar Northern Ireland.[80][81] Senior figures in Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and Greens have, with varying degrees of explicitness, all dismissed the idea.[82][83][84] There is also concern that such a proposal would not function as intended if implemented, as none of the 92 constituencies Unite to Remain operated in were successful, and some believe both that voters would react negatively to what could be perceived as “backroom deals” and “stitch-ups,” or that association with the other parties would harm each one's reputation with target voters.[85][86]

In Wales, the Senedd Cymru (Members and Elections) Act 2024 changed the electoral system for the Senedd from additional member using the D'Hondt method to proportional representation using closed lists.[87]

The UK Labour government elected in July 2024 has a manifesto commitment to restrict donations to political parties and reduce the minimum voting age from 18 to 16.[88]

United States

[edit]Electoral reform is a continuing process in the United States, motivated by concerns of both electoral fraud and disfranchisement. There are ongoing extensive debates of the fairness and effects of the Electoral College, existing voting systems, and campaign financing laws, as well as the proposals for reform. There are also initiatives to end gerrymandering, a process by which state legislatures alter the borders of representative districts to increase the chances of their candidates winning their seats (cracking), and concentrating opponents in specific districts to eliminate their influence in other districts (packing).

Ukraine

[edit]Ukraine reformed in 2020 from parallel voting to Proportional representation.[89]

References

[edit]- ^ https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/287/1/

- ^ "Multimember Districts: Advantages and Disadvantages".

- ^ Semini, Llazar (July 30, 2020). "Albania amends constitution aimed at holding better election". AP News.

- ^ Semini, Llazar (October 5, 2020). "Albania approves electoral code reform to boost EU prospects". AP News.

- ^ Farrell and McAllister. The Australian Electoral System. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Election Districts Voting. "New Proportional Representation Electoral Systems That Make Democracy Work". ElectionDistrictsVoting.com. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- ^ "Review Essay". Perspectives on Political Science. 31 (1): 46–63. January 2002. doi:10.1080/10457090209602384. ISSN 1045-7097. S2CID 220342303.

- ^ "British Columbia Referendum on Electoral Reform (2005) – Participedia". 17 May 2005.

- ^ MacLauchlan, Wade (8 November 2016). "Statement from Premier MacLauchlan regarding Plebiscite". Government of Prince Edward Island. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ a b Wherry, Aaron (8 December 2014). "The case for mixed-member proportional representation". Maclean's.

- ^ "Electoral Reform". Liberal Party of Canada. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Stephane Dion: Canada Needs a new Voting System". National Post.[dead link]

- ^ "Preferred Voting Model". Green Party of Canada. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Bryden, Joan (1 December 2016). "Electoral reform committee urges proportional vote referendum". Maclean's.

- ^ "Opposition cry 'betrayal' as Liberals abandon electoral reform". CBC News. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ^ Morrow, Adrian (24 February 2014). "Ontario proposal would let municipalities adopt ranked-ballot voting". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Election Districts Voting. "Proposal for a Modern AV PR Election Model". ElectionDistrictsVoting.com. Retrieved 2017-06-08.

- ^ "Why Canadians need a fair and proportional voting system" (PDF). Fair Vote Canada. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Czech court ruling on electoral law to help small parties". AP News. April 20, 2021.

- ^ "How did Denmark get proportional representation?". Electoral Reform Society.

- ^ "The European Parliament: electoral procedures". European Parliament. October 31, 2023.

- ^ "Germany's top court annuls 3% threshold for EU election". www.euractiv.com. February 27, 2014.

- ^ Hoffmeister, Kalojan (April 29, 2022). "All good things come in … four? Why the new draft on the European electoral act should be supported". www.euractiv.com.

- ^ "New Constitution Enters into Force". Civil Georgia. 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2024-10-23.

- ^ "Germany passes law to shrink its XXL parliament". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Maltezou, Renee (July 22, 2016). "Greek MPs approve end to bonus seats, lower voting age". Reuters.

- ^ "Greece to change election law, abandon proportional system". AP News. January 24, 2020.

- ^ "2011. évi CCIII. Törvény az országgyűlési képviselők választásáról – Hatályos Jogszabályok Gyűjteménye" (in Hungarian).

- ^ "Finance Bill 2017 passed in Lok Sabha". Economic Times. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Independent High Electoral Commission, Iraqi Council of Representatives Elections Law No. (9) of 2020

- ^ Feyzullah Tuna Aygün (Mar 2, 2023). "Iraq's Endless Electoral Law Debate". The Washington Institute.

- ^ "Lesotho and the limits of electoral reform". www.africaresearchinstitute.org. Africa Research Institute.

- ^ Law on Elections amended Montsame, 24 December 2019

- ^ Mongolia's new election rules handicap smaller parties, clear way for two-horse raceArchived 2016-07-01 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 20 May 2016

- ^ "Slovak parliament toughens pre-election polling rules before February vote". Reuters. October 28, 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "512/2021 Z.z. – Zákon, ktorým sa mení a dopĺňa záko..." Slov-lex.

- ^ "(3rd LD) National Assembly passes electoral reform bill amid opposition lawmakers' protest". Yonhap News Agency. December 27, 2019.

- ^ Admin, Blog (April 15, 2020). "How Does South Korea's New Election System Work?". Korea Economic Institute of America.

- ^ "How Rules Matter: Electoral Reform in Taiwan, Social Science, 2010". Social Science Quarterly. JSTOR 42956521.

- ^ "Voting age referendum to be held with elections – Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Thailand's New Electoral System". Thaidatapoints. March 21, 2019.

- ^ Yuda, Masayuki (16 September 2021). "Thai ruling party irks progressives with electoral tweaks". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Paul, History of Reform (1884), p. 63-69

- ^ a b Butler D (2004). "Electoral reform", Parliamentary Affairs, 57: 734-43

- ^ Royal commission appointed to enquire into electoral systems (1910). Report with Appendices. Command papers. Vol. Cd.5163. London: HMSO. p. 37, §139. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ "Clause 15 — Modification of Method of Voting in Certain Constituencies". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 4 July 1917. pp. HC Deb vol 95 cc1133–255. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Representation of the People Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 22 January 1918. HL Deb vol 27 cc973–974. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Clause 18 — Modification of Method of Voting in Certain Constituencies". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 31 January 1918. HC Deb vol 101 cc1778–1823. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Representation of the People Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 4 February 1918. HL Deb vol 28 cc321–56. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Consideration of Lords Amendments". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 6 February 1918. pp. HC Deb vol 101 cc2269–91. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Butler DE (1953), "The Electoral System in Britain 1918–1951", Oxford University Press

- ^ "Representation of the People (No. 2) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 3 February 1931. HC Deb vol 247 col 1773.

- ^ "Clause 1. — Voting at Parliamentary elections to be by method of alternative vote". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 4 March 1931. pp. HC Deb vol 249 cc536–537. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Representation of the People (No. 2) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 4 March 1931. HC Deb vol 249 cc415–6. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Representation of the People (No. 2) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 2 July 1931. HL Deb vol 81 cc565, 594–597. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Representation of the People (No. 2) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 2 July 1931. HL Deb vol 81 cc609–610. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Index for Representation of the People Bill No. 2". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Dates 1931–01–23 to 1931–07–27. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "European Parliamentary Elections Act 1999 (repealed)". Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ "The European Parliament: electoral procedures | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 2023-10-31. Retrieved 2024-04-20.

- ^ "1997 Labour Party Manifesto -". labour-party.org.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ Gallop, Nick in The Constitution and Constitutional Reform p.v29 (Philip Allan, 2011) ISBN 978-0340987209

- ^ Merrick, Jane; Brady, Brian; Owen, Jonathan; Smith, Lewis (9 May 2010). "Clegg is urged to abandon deal as Tories rule out vote reform – UK Politics". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ^ "2010 Conservative Manifesto" (PDF). Conservative Home. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-04-14. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b "2010 Labour Party Manifesto" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-29. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "AV referendum: Where parties stand". BBC News. 2011-04-26. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "AV: voters go to the polls to decide whether to change British voting system". The Daily Telegraph. London. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12.

- ^ "June poll was 'hold your nose election,' says vote reform campaign". BBC News. 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Square pegs, round hole". The Economist. 8 May 2015.

- ^ "The new government's constitutional reform agenda – and its challenges – The Constitution Unit Blog". The Constitution Unit Blog. 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Politics Live". BBC News. 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Grandee casts doubt over electoral system". BBC News. 30 April 2015.

- ^ The Last Leg, 30 April 2015, Channel 4

- ^ The Queen 'was opposed to changing voting system to proportional representation'. The Independent. Author – John Rentoul. Published 7 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Woodcock, Andrew (17 March 2021). "Priti Patel under fire over plan to change voting system for London mayor". The Independent.

- ^ Waterson, Jim (10 May 2021). "Queen's speech: voters will need photo ID for general elections". The Guardian.

- ^ "We Believe". Best for Britain. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Lib Dem North Shropshire victory: Stand asides needed in next general election". Best for Britain. December 17, 2021. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "New Analysis: Labour would win up to 351 seats by working with Greens and Lib Dems". Best for Britain. January 16, 2021. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Calls for a formal progressive alliance after Lib Dem win in North Shropshire". Left Foot Forward: Leading the UK's progressive debate. 2021-12-17. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Labour will not back proportional representation despite members' support". Politics.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Labour Party Constitution" (PDF). Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Pogrund, Gabriel. "Starmer's election tactics under fire as party critics try to quash talk of 'progressive alliance'". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Why progressive alliances in politics don't work | Daisy Cooper". The Independent. 2021-12-26. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "'There is nowhere we can't win,' say Greens". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "The false hope of a 'Progressive Alliance'". UK in a changing Europe. 2021-05-19. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "Why a progressive alliance pact would be a disaster for the left". New Statesman. 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "A way forward for Senedd reform". GOV.WALES. 10 May 2022.

- ^ Courea, Eleni (2 December 2024). "Government may cap UK political donations to limit foreign influence". The Guardian.

- ^ "Electoral Code becomes effective in Ukraine". Interfax-Ukraine.

Further reading

[edit]- Dummett, Michael (1997). Principles of Electoral Reform. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198292465

External links

[edit]International

[edit]- A Handbook of Electoral System Design Archived 2009-12-24 at the Wayback Machine from International IDEA

- ACE Project

United States

[edit]Canada

[edit]- Election Districts Voting

- Fair Vote Canada

- Paul McKeever's Testimony to the Select Committee on Electoral Reform (Canada) Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine: No electoral system is more "democratic" than any other

- Electoral Reform Canada

- Voting Reform Canada Archived 2013-02-09 at archive.today

- FPTP ... It Works for Canada / Notre Systeme Electoral ... Ca March pour Moi (Facebook group)