Saint-Roch, Paris

| Saint-Roch, Paris | |

|---|---|

Saint-Roch | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 284 Rue Saint-Honoré, 1e |

| State | France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°51′55″N 2°19′57″E / 48.86528°N 2.33250°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Parish church |

| Style | Baroque |

| Groundbreaking | 1653 |

| Completed | 1722 |

| Direction of façade | South |

| Official name: Eglise Saint-Roch | |

| Designated | 1914 |

| Reference no. | |

| Denomination | Église |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Church of Saint-Roch (French: Église Saint-Roch, pronounced [eɡliz sɛ̃ ʁɔk]) is a 17th–18th-century French Baroque and classical style church in Paris, dedicated to Saint Roch. It is located at 284 rue Saint-Honoré, in the 1st arrondissement. The current church was built between 1653 and 1740.[2][3]

The church is particularly noted for its very exuberant 18th century chapels decorated with elaborate Baroque murals, sculpture, and architectural detail. In 1795, during the later states of the French Revolution, the front of the church was the site of the 13 Vendémiaire, when the young artillery officer Napoleon Bonaparte fired a battery of cannon to break up a force of Royalist soldiers which threatened the new revolutionary government.[4]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

In 1521, the merchant Jean Dinocheau had a chapel built on the outskirts of Paris, which was dedicated to Saint Susanna. In 1577, his nephew Etienne Dinocheau had it extended into a larger church. In the early 18th century, with the beginning of the construction of the Tuileries Palace nearby, the neighbourhood began to grow, and a larger church was needed. The first stone was laid in 1653 by Louis XIV, accompanied by his mother Anne of Austria, The church was built by architect Jacques Lemercier, first architect of the King.[5] Lemercier's other works included the domed chapel of the Sorbonne, which served as an inspiration for the dome of Les Invalides.

The interior of Saint Roch largely followed the traditional Gothic floor-plan of Notre-Dame, but the facades and interior decoration were in the new Italian Baroque style, inspired by Saint-Gervais-Saint-Protais, the first Baroque church in Paris, which in turn was inspired by the Church of the Gesù in Rome, the first Baroque church in that city.[6] Texier also followed the advice of the Council of Trent, which promoted the Baroque style, to integrate churches into the city's architecture. The façade of Saint Roch aligned with the street, on a north–south axis, rather than the traditional east–west alignment.[6]

Financial difficulties arose, and in 1660 construction was halted. In 1690, the choir and the nave were completed, but had only a simple wooden roof. Work resumed 1701 under a new architect, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, who introduced a more inventive style. In the apse he constructed the Chapel of the Virgin, an elliptical space surrounded by a disambulatory. After his death, the chapel was finished ivy Pierre Bullet.[7]

18th−19th century

[edit]

Work on the church proceeded slowly, due to financial problems. In 1719, thanks to a gift from the Scottish economist and banker John Law, the facade and transept were finished.

Construction of the church continued throughout the 18th century. Between 1728 and 1736, Robert de Cotte built a tower on the right side of the choir, while an existing tower on the facade was destroyed in 1735. De Cotte made a plan for a new facade with two levels. The new facade was completed in 1739, probably finished by De Cotte's son Jules-Robert De Cotte. The lower level features Doric columns, while the upper level had Corninthian columns. The church continued to have a close association with the royal family; The tomb of Marie Anne de Bourbon, the Princess de Conti and illegitimate daughter of Louis XIV, was placed there in 1739.[8]

Jean-Baptiste Marduel, the pastor of the church between 1750 and 1770, called upon the most important painters and sculptors in Paris to give the church a new decor. In 1754 the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée built a new domed chapel, dedicated to the events of the Crucifixion. The major painters and sculptors of period, including Étienne Maurice Falconet, Joseph-Marie Vien and Gabriel-François Doyen participated in its decoration. In 1756, Jean-Baptiste Pierre painted a mural depicting the Assumption for the new dome over the Chapel of the Virgin. The sculptor Falconet made a work depicting "Glory" over the arcade behind the altar of the Virgin, modeled after the sculpture of the same subject in Saint Peters Basilica in Rome. He made two other sculptures, a group depicting the Announcation and a statue of Christ on the Cross in the Calvary Chapel, but these works disappeared during the French Revolution.[9]

En 1758, Jean-Baptiste Marduel designed a dramatic new pulpit, which was made by sculptor Simon Challet. It was remodelled twice, and the only remaining portion of the original today is the upper level, as well as a group of paintings and sculptures created for it, now located in the transept.[10]

In 1795 The church became the site of the 13 Vendémiaire, one of the major events of the late French Revolution. On 5 October 1795, a large force of royalist soldiers occupied the street and the steps in front of the church, and threatened to seize power in Paris and restore the monarchy, They were confronted by the young Napoleon Bonaparte, who supported the Revolution and commanded a battery of artillery. His guns opened fire on the royalists, clearing the steps and securing the street. This event made him a hero and ally of the Revolution, and opened the way for his rapid rise to power.[11] The marks of the cannon fire can still be seen on the front of the church.

The church was closed most of the French Revolution, and was stripped of much of its art and decoration. It was returned to the church in 1801. Some the art works stolen during the Revolution were returned, while other paintings and sculptures from other churches which were destroyed found a new home at Saint-Roch.[12]

The 19th century saw more modifications. IN 1850, the Chapel of Calvary built by Boullée, was redesigned and rebuilt into the present Chapel of Catechisms. In 1879, the bell tower on the right side of the church, destabilised by the construction of the Avenue de l'Opera next to it, was demolished.

Exterior

[edit]-

The south front

-

Detail of the south front

-

Passage Saint-Roch (east side)

The design of the facade was inspired by the Church of the Gesù n Rome, the mother church of the Jesuit order and first Baroque church in Rome, and even more by Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis (1641, the first Baroque church in Paris.[13] Following the classical style, the columns of the lower level have Doric order capitals, while the columns of the upper level have Corinthian order columns. The church is exceptionally long (126 meters), making it one of the largest churches in Paris.

The statue in the niche on the left side of the facade is Saint Honoratus by Eugène Aizelin (1873).

Interior

[edit]

While the church was not particularly wide, and did not have a bell tower or spire, it became exceptionally long and tall by the creation of a series of lavish chapels and the creation of soaring domes and cupolas. In its design, it followed the precepts of the Council of Trent in 1545–1563, intended to make church interiors more welcoming and dramatic, as a way combat the more austere architecture of the new Protestant churches. The Council of Trent dictated the form a church should take:

"...A church in the form of a Latin cross, with a single nave, surrounded by communicating chapels, with a transept slightly protruding, covered with barrel vaults, high windows, a cupola at the crossing, and a facade with two orders of columns superimposed, of unequal size, topped by a fronton."[14]

The present appearance of the interior and its succession of chapels was largely the work of Abbot Jean-Baptiste Marduel, beginning in 1753. It was carried out by the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée assisted by the sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet. This consists of a series of three chapels, symbolising the Incarnation of Christ (the Chapel of the Virgin); The Transubstantiation, (the Chapel of the Communion), and the Redemption[15]

The nave and choir

[edit]-

Remnant of the Baroque pulpit in the nave

-

The nave.

-

The nave, with pulpit at left, and choir beyond

-

Transept arcade, with "The Predication of Saint Denis", by Joseph-Marie Vien

-

Dome over the transept

The nave, covered with barrel vaults, is constructed in the classical style; the columns, have Doric capitals pilasters, are joined into arcades which support classical entablature and other classical elements. One distinctive Baroque element remaining in the nave is a portion of the original pulpit, built by Simon Challe in the 18th century. Only the sculptural upper portion survives, titled "The Genius of Truth Lifting the Veil of Error" (1752)[16]

The transept of the church, following the doctrine of the Council of Trent, did not projet out very far, but was given the illusion of depth through imaginative works of two painters, "The Miracle of the Ardent" by Gabriel-Francois Doyen and "The Vision of Saint Denis", by Joseph-Marie Vien. Vien (1716–1809) was the last official Painter of the King before the French Revolution. The paintings give the impression of looking through a classical gateway into the scene beyond.[17]

The choir of the church was extended with new chapels beginning in 1753 by the Abbot Jean-Baptiste Marduel, who was the Curé of the Parish. The new additions were designed by the neoclassical architect Étienne-Louis Boullée in collaboration with sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet. It contains several notable works of 18th-century art, including a sculpture by Falconet depicting "Christ in the Garden of Olives."

The chapels

[edit]-

The Chapel of the Virgin, at the north end of the church

-

"The Assumption" by Jean-Baptiste Pierre (dome of the Chapel of the Virgin)

The Chapel of the Virgin, just north of the choir was designed by François Mansart. It is a major landmark of French Baroque art, notable for both its architecture and the paintings and sculpture it contains. Its features include an enormous oval dome, decorated with a painting of the Assumption by Jean-Baptiste Pierre (1714–1789). This work was criticised as out-of-date by Denis Diderot, the co-author of the first Encyclopédie, but was praised the time by more traditional critics.[18]

Art and decoration

[edit]Sculpture

[edit]-

"The Baptism of Christ" by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne

-

The "Pieta of Saint Roch", by Frédéric Bogino, Chapel of Compassion (1856)

-

The funeral monument of Henri and Alphonse de Lorraine-Harcourt

-

"THe Nativity" by Michel Anguier (17th c., Chapel of the Communion)

The church, particularly the chapels at the north end, has an extensive collection of paintings and sculpture by some of the most prominent French artists of the 18th and 19th centuries. The Chapel of the Baptismal Fonts is decorated by murals by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856), illustrating "The Baptism of the Eunoch and Saint Francis-Xavier surrounded by the people they covered." The painting is complemented by the marble sculptures by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1681–1732) and his nephew J.B. II Lemoyne. Typical of the Baroque style and the influence of Bernini and Puget, they emphasise twisting postures and movement.[19] "The Nativity" is a work by Michel Anguier from the 17th century, located in the Chapel of Calvary. His other major works include a marble group of the Nativity in the church of Val-de-Grâce, the sculptures of the triumphal arch at the Porte Saint-Denis (c. 1674), which served as a memorial of the conquests of Louis XIV, the decoration of the apartments of Anne of Austria in the old Louvre, and the Chateau of Nicolas Fouquet, Vaux-le-Vicomte. In the 21st century this work was restored and given a special position and lighting to mark the focal point of he Chapel of the Communion [20]

Painting

[edit]-

"Saint Denis Preaching in Gaul" by Joseph-Marie Vien (1767) (transept)

-

"The Miracle of the Ardents" by Gabriel-François Doyen (transept)

-

"Souls in Purgatory" by Louis Boulanger (1850)

-

"The Deposition of the Cross" by Charles Le Brun(17th c.)

-

"The Triumph of Mardochée" by Jean Restout (1755)

-

"The Return of the Prodigal Son" by Jean-Germain Drouais (1763-1788)[21]

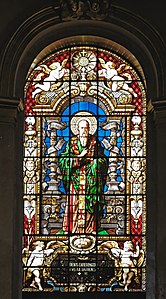

Stained glass

[edit]-

"Window of Denys Affre" Bishop martyred in 1848 Revolution

-

Detail of the "Gloire Divine" window (Chapel of the Virgin)

-

"Saint Denis l'aeropagite" (19th c.)

-

"The Crucifixion"

The stained glass in the church mostly dates to the 19th and 20th century. One unusual window is that devoted to Denys Affre, the Archbishop of Paris, who was killed while trying to negotiate a truce during the June Days uprising of 1848.[22]

One small window, surrounded by Cherubs, is located in the center the "Gloire Divine" sculptural piece which dominates the Chapel of the Virgin.

Other notable windows are:

- Christ on the Cross", (Lower north side), (1816) the oldest 19th century window, by Ferdinand Henri Joseph Mortelèque, following a design by Regnier.[23]

- "Saint John the Baptist" (end of 19th century)

- "The Death of Saint Joseph" (Chapel of Calvary, by the Lorin workshop (about 1880), Calvary Chapel

- " Saint Denis l'aréopagyte" in the chapel of the Communion

The grand organ

[edit]

The original organ was built in 1752 by Louis-Alexandre Cliquot, and redone by his son, François-Henri Clicquot in 1769.The organ deteriorated during the French Revolution, and was rebuilt by Pierre-François Dallery in 1826. All that remains of the 1752 instrument is the wooden case. The organ has four keyboards plus pedals, fifty three "jeux" or effects, controlled mechanically from the keyboard, and two thousand, eight hundred thirty-two pipes.

Notable tombs

[edit]The church contains the memorials of fashion designer Yves Henri Donat Mathieu-Saint-Laurent,Denis Diderot, the Comte de Grasse, Baron d'Holbach, Henri de Lorraine-Harcourt, the playwright Pierre Corneille,André le Nôtre, Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin and Marie Anne de Bourbon, daughter of Louis XIV, and Claude-Adrien Helvétius. In 1791, several tombs were relocated from the Couvent des Jacobins, Saint-Honoré when it was taken over by Jacobin Club; they included that of the soldier François de Créquy (1629–1687), designed by Charles Le Brun and executed by Antoine Coysevox, and the painter Pierre Mignard (1612–1695).

Other notable burials included César de Vendôme (1664), René Duguay-Trouin (1736), Claude-Adrien Helvétius (1771), and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1806), while the Marquis de Sade, the Marquis de Lafayette and Vauban were among those married in this church.[24]

After the failed November 1830 Polish Uprising, Saint-Roch became known as the 'Polish church' due to the many exiles who attended service there; they included Chopin (1810–1849), who allegedly composed a Veni Creator prayer he played on the church organ during Mass.[25]

On 18 November 1880 Prince Roland Bonaparte and Marie-Félix Blanc were married at the church.

In 1825 a mass composed by Hector Berlioz was performed at the church.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00085798 Eglise Saint-Roch (in French)

- ^ Blackmore, Ruth (2012). The Rough Guide to Paris. London: Rough Guides. p. 71. ISBN 978-1405386951.

- ^ Dumoulin, Aline, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 35

- ^ Dumoulin (2012), "Églises de Paris", p. 35-37

- ^ Dumoulin (2012), "Églises de Paris", p. 35

- ^ a b Texier 2012, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Dumoulin (2012), "Églises de Paris", p. 35

- ^ Description of the church in Insecula.com (in French)

- ^ Description of the church in Insecula.com (in French)

- ^ Description of the church in Insecula.com (in French)

- ^ Petit Larousse de l'Histoire de France",(2004) p. 295

- ^ Dumoulin (2010), p. 35

- ^ Dumoulin (2010), p. 35

- ^ Mignot, Claude, Rabreau, Daniel, Temps modernes (15th–18th centuries), Histoire de l'Art Flammarion, Paris 2005, 2007, ISBN 2080116029, page 380

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 35

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 35

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 36

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 37

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 39

- ^ Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris", (2010), p. 39

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Drouais, Jean Germain". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 591–592.

- ^ Grey, Francis. "Denis Auguste Affre." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 19 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ de Finance, Laurence, " Chronologie de la renaissance du vitrail à Paris au XIXe siècle", (in French) "Revue du patrimoine (2008)

- ^ Morgan, George (1919). The True LaFayette. Lippincott.

- ^ Szulc, Tad (1998). Chopin In Paris: The Life and Times of the Romantic Composer (1999 ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0306809330.

Bibliography (in French)

[edit]- Brisac, Catherine (1994). Le Vitrail (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 2-73-242117-0.

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1

- Hillairet, Jacques; Connaissance du Vieux Paris; (2017); Éditions Payot-Rivages, Paris; (in French). ISBN 978-2-2289-1911-1

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris- Panorama de l'architecture. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

External links

[edit]- Website (in French)

- Structurae

- Description of the church (in French)

!["The Return of the Prodigal Son" by Jean-Germain Drouais (1763-1788)[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Drouais_-_Le_Retour_du_fils_prodigue.JPG/432px-Drouais_-_Le_Retour_du_fils_prodigue.JPG)