Darrieus wind turbine

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2013) |

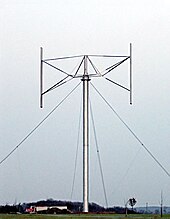

The Darrieus wind turbine is a type of vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) used to generate electricity from wind energy. The turbine consists of a number of curved aerofoil blades mounted on a rotating shaft or framework. The curvature of the blades allows the blade to be stressed only in tension at high rotating speeds. There are several closely related wind turbines that use straight blades. This design of the turbine was patented by Georges Jean Marie Darrieus, a French aeronautical engineer; filing for the patent was October 1, 1926. There are major difficulties in protecting the Darrieus turbine from extreme wind conditions and in making it self-starting.

Method of operation

[edit]

In the original versions of the Darrieus design, the aerofoils are arranged so that they are symmetrical and have zero rigging angle, that is, the angle that the aerofoils are set relative to the structure on which they are mounted. This arrangement is equally effective no matter which direction the wind is blowing—in contrast to the conventional type, which must be rotated to face into the wind.

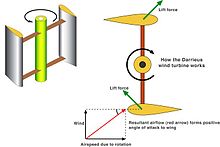

When the Darrieus rotor is spinning, the aerofoils are moving forward through the air in a circular path. Relative to the blade, this oncoming airflow is added vectorially to the wind, so that the resultant airflow creates a varying small positive angle of attack to the blade. This generates a net force pointing obliquely forwards along a certain "line of action". This force can be projected inwards past the turbine axis at a certain distance, giving a positive torque to the shaft, thus helping it to rotate in the direction it is already travelling in. The aerodynamic principles which rotate the rotor are equivalent to that in autogiros, and normal helicopters in autorotation.

As the aerofoil moves around the back of the apparatus, the angle of attack changes to the opposite sign, but the generated force is still obliquely in the direction of rotation, because the wings are symmetrical and the rigging angle is zero. The rotor spins at a rate unrelated to the windspeed, and usually many times faster. The energy arising from the torque and speed may be extracted and converted into useful power by using an electrical generator.

The aeronautical terms lift and drag are, strictly speaking, forces across and along the approaching net relative airflow respectively, so they are not useful here. The forces at play are rather tangential force, which pulls the blade around, and radial force, which acts against the bearings.

When the rotor is stationary, no net rotational force arises, even if the wind speed rises quite high—the rotor must already be spinning to generate torque. Thus the design is not normally self-starting. Under rare conditions, Darrieus rotors can self-start, so some form of brake is required to hold it when stopped.

One problem with the design is that the angle of attack changes as the turbine spins, so each blade generates its maximum torque at two points on its cycle (front and back of the turbine). This leads to a sinusoidal (pulsing) power cycle that complicates design. In particular, almost all Darrieus turbines have resonant modes where, at a particular rotational speed, the pulsing is at a natural frequency of the blades that can cause them to (eventually) break. For this reason, most Darrieus turbines have mechanical brakes or other speed control devices to keep the turbine from spinning at these speeds for any lengthy period of time.

Another problem arises because the majority of the mass of the rotating mechanism is at the periphery rather than at the hub, as it is with a propeller. This leads to very high centrifugal stresses on the mechanism, which must be stronger and heavier than otherwise to withstand them. One common approach to minimise this is to curve the wings into an "egg-beater" shape (this is called a "troposkein" shape, derived from the Greek for "the shape of a spun rope") such that they are self-supporting and do not require such heavy supports and mountings. See. Fig. 1.

In this configuration, the Darrieus design is theoretically less expensive than a conventional type, as most of the stress is in the blades which torque against the generator located at the bottom of the turbine. The only forces that need to be balanced out vertically are the compression load due to the blades flexing outward (thus attempting to "squeeze" the tower), and the wind force trying to blow the whole turbine over, half of which is transmitted to the bottom and the other half of which can easily be offset with guy wires.

By contrast, a conventional design has all of the force of the wind attempting to push the tower over at the top, where the main bearing is located. Additionally, one cannot easily use guy wires to offset this load, because the propeller spins both above and below the top of the tower. Thus the conventional design requires a strong tower that grows dramatically with the size of the propeller. Modern designs can compensate most tower loads of that variable speed and variable pitch.

In overall comparison, while there are some advantages in Darrieus design there are many more disadvantages, especially with bigger machines in the MW class. The Darrieus design uses much more expensive material in blades while most of the blade is too close to the ground to give any real power. Traditional designs assume that the wing tip is at least 40 m from ground at lowest point to maximize energy production and lifetime. So far there is no known material (not even carbon fiber) which can meet cyclic load requirements.[citation needed]

Giromills

[edit]

Darrieus's 1927 patent also covered practically any possible arrangement using vertical airfoils. One of the more common types is the H-rotor,[1][2][3] also called the Giromill or H-bar design, in which the long "egg beater" blades of the common Darrieus design are replaced with straight vertical blade sections attached to the central tower with horizontal supports. This design is used by Shanghai based MUCE.[4][5]

Cycloturbines

[edit]Another variation of the Giromill is the Cycloturbine, in which each blade is mounted so that it can rotate around its own vertical axis. This allows the blades to be "pitched" so that they always have some angle of attack relative to the wind. The main advantage to this design is that the torque generated remains almost constant over a fairly wide angle, so a Cycloturbine with three or four blades has a fairly constant torque. Over this range of angles, the torque itself is near the maximum possible, meaning that the system also generates more power. The Cycloturbine also has the advantage of being able to self-start, by pitching the "downwind moving" blade flat to the wind to generate drag and start the turbine spinning at a low speed. On the downside, the blade pitching mechanism is complex and generally heavy, and some sort of wind-direction sensor needs to be added in order to pitch the blades properly.

Helical blades

[edit]The blades of a Darrieus turbine can be canted into a helix, e.g. three blades and a helical twist of 60 degrees. The original designer of the helical turbine is Ulrich Stampa (Germany patent DE2948060A1, 1979). A. Gorlov proposed a similar design in 1995 (Gorlov's water turbines). Since the wind pulls each blade around on both the windward and leeward sides of the turbine, this feature spreads the torque evenly over the entire revolution, thus preventing destructive pulsations. This design is used by the Turby, Urban Green Energy, Enessere, Aerotecture and Quiet Revolution brands of wind turbine.

Active lift turbine

[edit]

The relative speed creates a force on the blade. This force can be decomposed into an axial and normal force (Fig. 5). In the case of a Darrieus turbine, the axial force associated with the radius creates a torque and the normal force creates on the arm a stress alternately for each half turn, a compression stress and an extension stress. With a crank rod system (Fig. 6), the principle of the Active Lift Turbine is to transform this alternative constraint into an additional energy recovery.[6][7]

References

[edit]- ^ S. Brusca, R. Lanzafame, M. Messina. "Design of a vertical-axis wind turbine: how the aspect ratio affects the turbine’s performance". 2014.

- ^ Mats Wahl. "Designing an H-rotor type Wind Turbine for Operation on Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station". 2007.

- ^ "H-rotor picture (page22)" (PDF).

- ^ "VAWT,Vertical Axis Wind Turbine - MUCE VAWT,上海模斯翼风力发电设备有限公司". www.vawtmuce.com.

- ^ "Overcoming the Barriers to Renewable Embedded Generation in Tasmania: Appendix 13 Discussion – Peter Fischer, Director,Tasmanian Planning Commission" (PDF). Goanna Energy Consulting Pty Ltd. September 10, 2010. p. 195. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

(Vertical Muce) turbines on the MarineBoard building

- ^ Lecanu, Pierre normandajc and Breard, Joel and Mouaze, Dominique, Simplified theory of an active lift turbine with controlled displacement, 15 Apr 2016

- ^ Lecanu, Pierre normandajc and Breard, Joel and Mouaze, Dominique, Operating principle of an active lift turbine with controlled displacement, Jul 2018