Burr puzzle

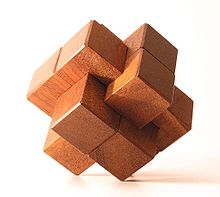

A burr puzzle is an interlocking puzzle consisting of notched sticks, combined to make one three-dimensional, usually symmetrical unit. These puzzles are traditionally made of wood, but versions made of plastic or metal can also be found. Quality burr puzzles are usually precision-made for easy sliding and accurate fitting of the pieces. In recent years the definition of "burr" is expanding, as puzzle designers use this name for puzzles not necessarily of stick-based pieces.

History

[edit]The term "burr" is first mentioned in a 1928 book by Edwin Wyatt,[1] but the text implies that it was commonly used before. The term is attributed to the finished shape of many of these puzzles, resembling a seed burr. The origin of burr puzzles is unknown. The first known record[2] appears in a 1698 engraving used as a frontispiece page of Chambers's Cyclopaedia.[3][better source needed] Later records can be found in German catalogs from the late 18th century and early 19th century.[4] There are claims of the burr being a Chinese invention, like other classic puzzles such as the Tangram.[5] In Kerala, India, these wooden puzzles are called edakoodam(ഏടാകൂടം).[6][7]

Six-piece burr

[edit]

The six-piece burr, also called "Puzzle Knot" or "Chinese Cross", is the most well-known and presumably the oldest of the burr puzzles. This is actually a family of puzzles, all sharing the same finished shape and basic shape of the pieces. The earliest US patent for a puzzle of this kind dates back to 1917.[8]

For many years, the six-piece burr was very common and popular, but was considered trite and uninteresting by enthusiasts. Most of the puzzles made and sold were very similar to one another and most of them included a "key" piece, an unnotched stick that slides easily out. In the late 1970s, however, the six-piece burr regained the attention of inventors and collectors, thanks largely to a computer analysis conducted by the mathematically trained puzzle designer Bill Cutler which was published by Martin Gardner in his Mathematical Games column in Scientific American.[9]

Structure

[edit]All six pieces of the puzzle are square sticks of equal length (at least 3 times their width). When solved, the pieces are arranged in three perpendicular, mutually intersecting pairs. The notches of all sticks are located within the region of intersection, so when the puzzle is assembled they are unseen. All notches can be described as being made by removing cubic units (with an edge length of half the sticks' width), as shown in the figure:

There are 12 removable cubic units, and different puzzles of this family are made of sticks with different units removed. 4,096 permutations exist for removing the cubic units. Of those, we ignore the ones that cut the stick in two and the ones creating identical pieces, and are left with 837 usable pieces.[10] Theoretically, these pieces can be combined to create over 35 billion possible assemblies, but it is estimated that fewer than six billion of them are actual puzzles, capable of being assembled or taken apart.[11]

Solid burr

[edit]A burr puzzle with no internal voids when assembled is called a solid burr. These burrs can be taken apart directly by removing a piece or some pieces in one move. Up until the late 1970s, solid burrs received the most attention and publications referred only to this type.[13] 119,979 solid burrs are possible, using 369 of the usable pieces. To assemble all these puzzles, one would need a set of 485 pieces, as some of the puzzles include identical pieces.[10]

Pieces types

[edit]For aesthetic, but mostly practical reasons, the burr pieces can be divided into three types:

- Notchable pieces - with full notches running perpendicular to the long axis that can be made with a saw

- Millable pieces - with no internal blind corners that can be made with a milling machine.

- Non-notchable pieces - with internal corners that have to be made with a chisel or by gluing parts together.

59 of the usable pieces are notchable, including the unnotched stick. Of those, only 25 can be used to create solid burrs. This set, often referred to as "The 25 notchable pieces", with the addition of 17 duplicates, can be assembled to create 221 different solid burr puzzles. Some of those puzzles have more than one solution, for a total of 314 solutions. These pieces are very popular, and full sets are manufactured and sold by many companies.

Holey burr

[edit]For all solid burrs, one movement is required to remove the first piece or pieces. However, a holey burr, which has internal voids when assembled, can require more than one move. The number of moves required for removing the first piece is referred to as the level of the burr. All solid burrs are therefore level 1. The higher the level is, the more difficult the puzzle.

During the 1970s and 1980s, attempts were made by experts to find burrs of an ever-higher level. On 1979, the American designer and craftsman Stewart Coffin found a level-3 puzzle. In 1985, Bill Cutler found a level-5 burr[14] and shortly afterwards a level-7 burr was found by the Israeli Philippe Dubois.[13] In 1990, Cutler completed the final part of his analysis and found that the highest possible level using notchable pieces is 5, and 139 of those puzzles exist. The highest level possible for a six-piece burr with more than one solution is 12, meaning 12 moves are required to remove the first piece.[11]

Three-piece burr

[edit]

A three-piece burr made from sticks with "regular" right-angled notches (as the six-piece burr), cannot be assembled or taken apart.[15] There are, however, some three-piece burrs with different kinds of notches, the best known of them being the one mentioned by Wyatt in his 1928 book, consisting of a rounded piece that is meant to be rotated.[1]

Known families

[edit]Altekruse

[edit]

The Altekruse puzzle is named after the grantee of its 1890 patent, though the puzzle is of earlier origin.[16] The name "Altekruse" is of Austrian-German origin and means "old-cross" in German, which led to the presumption that it was a pseudonym, but a man by that name immigrated to America in 1844 with his three brothers to avoid being drafted to the Prussian Army and is presumed to be the one who filed this patent.[17]

A classic Altekruse consists of 12 identical pieces. In order to disassemble it, two halves of the puzzle have to be moved in opposite directions. Using two more of these pieces, the puzzle can be assembled in a different way. By the same principle, other puzzles of this family can be created, with 6, 24, 36 and so forth. Despite their size, those bigger puzzles are not considered very difficult, yet they require patience and dexterity to assemble.

Chuck

[edit]

The Chuck puzzle was invented and patented by Edward Nelson in 1897.[18] His design was improved and developed by Ron Cook of the British company Pentangle Puzzles who designed other puzzles of the family.[19]

The Chuck consists mostly of U-shaped stick pieces of various lengths, and some with an extra notch that are used as key pieces. For creating bigger Chuck puzzles (named Papa-chuck, Grandpapachuck and Great Grandpapachuck, by Cook) one would need to add longer pieces. The Chuck can also be regarded as an extension of a six-piece burr of very simple pieces called Baby-chuck, which is very easy to solve. Chuck pieces of different lengths can also be used to create asymmetric shapes, assembled according to the same principle as the original puzzle.

Pagoda

[edit]

The origin of the Pagoda, also called "Japanese Crystal" is unknown. It is mentioned in Wyatt's 1928 book.[1] Puzzles of this family can be regarded as an extension of the "three-piece burr" (Pagoda of size 1), however they do not require special notches to be assembled or taken apart. Pagoda of size 2 consists of 9 pieces, and bigger versions consist of 19, 33, 51 and so forth. Pagoda of size consists of pieces.

Diagonal burr

[edit]

Though most burr puzzle pieces are made with square notches, some are made with diagonal notches. Diagonal burr pieces are square sticks with V-shaped notches, cut at an angle of 45° off the stick's face. These puzzles are often called "stars", as it is customary to also cut the sticks' edges at an angle of 45°, for aesthetic reasons, giving the assembled puzzle a star-like shape.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wyatt, E. M. (1928). Puzzles in Wood. Milwaukee, Wisc: Bruce Publishing Co. ISBN 0-918036-09-7.

- ^ Slocum, Jerry, New Findings on the History of the Six Piece Burr, Slocum Puzzle Foundation

- ^ The Frontispiece page of Chambers's Cyclopaedia on Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Slocum, Jerry; Gebbardt, Dieter (1997), Puzzles from Catel's Cabinet and Bestelmeier's Magazine, 1785 to 1823, Slocum Puzzle Foundation

- ^ Zhang, Wei; Rasmussen, Peter (2008), Chinese Puzzles: Games for the Hands and Mind, Art Media Resources, ISBN 978-1588861016 (A page about burr puzzles in the book's website)

- ^ "ഏടാകൂടം", Olam Dictionary (in Malayalam)

- ^ "നാലുകെട്ടല്ല ഇത് ഏടാകൂടം", Mathrubhumi Daily (in Malayalam), archived from the original on 2017-04-05, retrieved 2017-04-17

- ^ US 1225760, Brown, Oscar, "Puzzle", issued 1917

- ^ Gardner, Martin (January 1978), "Mathematical Games" (PDF), Scientific American, 238: 14–26, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0178-14

- ^ a b Cutler, William H. (1978), "The Six-Piece Burr", Journal of Recreational Mathematics, 10 (4): 241–250

- ^ a b Cutler, Bill (1994), A Computer Analysis of All 6-Piece Burrs, retrieved February 17, 2013

- ^ Hoffmann, Professor (1893), "Chapter III, No. XXXVI", Puzzles old and new, London: Frederick Warne and Co. (Available for download at the Internet Archive)

- ^ a b Coffin, Stewart (1992), Puzzle Craft (PDF)

- ^ Dewdney, A. K. (October 1985), "Computer Recreations", Scientific American, 253 (4): 16–27, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1085-16

- ^ Jürg von Känel (1997), Three-piece burrs, IBM, archived from the original on January 11, 2012, retrieved February 19, 2013

- ^ US 430502, Altekruse, William, "Block Puzzle", issued 1890

- ^ Coffin, Stewart (1998), "The Altekruse Puzzle", The Puzzling World of Polyhedral Dissections, retrieved February 19, 2013

- ^ US 588705, Nelson, Edward, "Puzzle", issued 1897

- ^ WoodChuck Puzzles, Pentangle Puzzles, archived from the original on August 5, 2013, retrieved February 19, 2013

Further reading

[edit]- Coffin, Stewart T. (2007). Geometric Puzzle Design. Wellsley, K. Peters. ISBN 978-1568813127.

- Wyatt, Edwin Mather (2007). Puzzles in Wood (3rd ed.). Fox Chapel Publishing. ISBN 978-1565233485.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Burr puzzles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Burr puzzles at Wikimedia Commons

- Coffin, Stewart (1998), The Puzzling World of Polyhedral Dissections (Online ed.), retrieved February 19, 2013 - Previous edition of his book Geometric Puzzle Design.

- Keiichiro, Ishino, Puzzle will be played..., retrieved February 19, 2013 - With hundreds of burr puzzles described.

- "Interlocking Puzzles", Rob's Puzzle Page, retrieved February 19, 2013

- Jürg von Känel (1997), IBM Research: The burr puzzles site, IBM, archived from the original on October 13, 2012, retrieved February 19, 2013

- Things tagged with burr puzzle on Thingiverse, thingiverse