Easter: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 202.171.172.90 to last revision by Ceiriog (HG) |

Tag: blanking |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Cultural elements, such as the [[Easter Bunny]], have become part of the holiday's modern celebrations, and those aspects are often celebrated by many Christians and non-Christians alike. There are also some Christian denominations who do not celebrate Easter. |

Cultural elements, such as the [[Easter Bunny]], have become part of the holiday's modern celebrations, and those aspects are often celebrated by many Christians and non-Christians alike. There are also some Christian denominations who do not celebrate Easter. |

||

ahahhahahahahahahah losar easter i stole ur cocolates AHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAGHAGHHA:P |

|||

==Theological significance== |

|||

The [[New Testament]] links the [[Last Supper]] and [[Passion (Christianity)|Jesus’ crucifixion]] with [[Passover]] and the [[Exodus from Egypt]]. As Jesus prepared himself and his disciples for his death in the upper room during the Last Supper, he gave the Passover meal a new meaning. He identified the loaf of bread and cup of wine as symbolizing [[Body of Christ|his body]] soon to be [[Substitutionary atonement|sacrificed]] and [[Blood of Christ|his blood]] soon to be shed. {{bibleverse|1|Corinthians|5:7|NIV}} states, "Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed"; this refers to the Passover requirement to have no yeast in the house and to Christ's identification as the [[Paschal lamb]].<ref>cf. {{bibleverse||John|1:29}}, {{bibleverse||Revelation|5:6}}, {{bibleverse|1|Peter|1:19}}, {{bibleverse|1|Peter|1:2}}, and the associated notes and Passion Week table in {{cite book|editor=Barker, Kenneth|title=Zondervan NIV Study Bible|publisher=[[Zondervan]]|location=[[Grand Rapids]]|year=2002|isbn=0310929555|page=1520, etc}}</ref> |

|||

One interpretation of the [[Gospel of John]] is that Jesus, as the Passover lamb, was crucified at roughly the same time as the Passover lambs were being slain in the temple, on the afternoon of [[Quartodecimanism|Nisan 14]].<ref>{{bibleverse||Exodus|12:6}}.</ref><ref>The scriptural instructions specify that the lamb is to be slain "between the two evenings", that is, at twilight. By the Roman period, however, the sacrifices were performed in the mid-afternoon. Josephus, ''Jewish War'' 6.10.1/423 ("They sacrifice from the ninth to the eleventh hour"). Philo, ''Special Laws'' 2.27/145 ("Many myriads of victims from noon till eventide are offered by the whole people").</ref> This interpretation, however, is inconsistent with the [[chronology of Jesus|chronology]] in the [[Synoptic Gospels]]. It assumes that "the preparation of the passover" in {{bibleverse||John|19:14|KJV}} literally refers to Nisan 14 (Preparation Day for the Passover) and not necessarily to [[Yom Shishi]] (Friday, Preparation Day for the [[Sabbath]])<ref>{{bibleverse||John|13:2}}, {{bibleverse||John|18:28}}, {{bibleverse||John|19:14}}, and the associated notes in {{cite book|editor=Barker, Kenneth|title=Zondervan NIV Study Bible|publisher=[[Zondervan]]|location=[[Grand Rapids]]|year=2002|isbn=0310929555}}</ref> and that "eat the passover" in {{bibleverse||John|18:28|KJV}} refers to the eating of the Passover lamb, not to eating any of the sacrifices that were offered during the Days of Unleavened Bread. |

|||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Revision as of 22:24, 26 March 2009

| Easter | |

|---|---|

16th century Russian Orthodox icon of the Descent into Hades of Jesus Christ, which is the usual Orthodox icon for Pascha. | |

| Observed by | Most Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Celebrates the resurrection of Jesus |

| Celebrations | Religious (church) services, festive family meals, Easter egg hunts, and gift-giving (latter two, especially in USA and Canada) |

| Observances | Prayer, all-night vigil (almost exclusively Eastern traditions), sunrise service (especially American Protestant traditions) |

| Date | March 22, April 25, date of Easter |

| 2025 date | |

| Related to | Passover, of which it is regarded the Christian equivalent; Septuagesima, Sexagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter; and Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, and Corpus Christi which follow it. |

Easter (Template:Lang-el) is the most important religious feast in the Christian liturgical year.[1] Christians believe that Jesus was resurrected from the dead three days[2] after his crucifixion. Many Christian denominations celebrate this resurrection on Easter Day or Easter Sunday[3] (also Resurrection Day or Resurrection Sunday), two days after Good Friday. The chronology of his death and resurrection is variously estimated between the years 26 and 36 A.D.

Easter also refers to the season of the church year called Eastertide or the Easter Season. Traditionally the Easter Season lasted for the forty days from Easter Day until Ascension Day but now officially lasts for the fifty days until Pentecost. The first week of the Easter Season is known as Easter Week or the Octave of Easter. Easter also marks the end of Lent, a season of prayer and penance.

Easter is a moveable feast, meaning it is not fixed in relation to the civil calendar. Easter falls at some point between late March and late April each year (early April to early May in Eastern Christianity), following the cycle of the Moon. After several centuries of disagreement, all churches accepted the computation of the Alexandrian Church (now the Coptic Church) that Easter is the first Sunday after the Paschal Full Moon, which is the first moon whose 14th day (the ecclesiastic "full moon") is on or after March 21 (the ecclesiastic "vernal equinox").

Easter is linked to the Jewish Passover not only for much of its symbolism but also for its position in the calendar. It is also linked to Spring Break, a secular school holiday (customarily a week long) celebrated at various times across North America, and characterized by road trips and bacchanalia.

Cultural elements, such as the Easter Bunny, have become part of the holiday's modern celebrations, and those aspects are often celebrated by many Christians and non-Christians alike. There are also some Christian denominations who do not celebrate Easter.

ahahhahahahahahahah losar easter i stole ur cocolates AHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAGHAGHHA:P

Etymology

Anglo-Saxon

The modern English term Easter developed from the Old English word Ēastre or Ēostre, which itself developed prior to 899. The name refers to Eostur-monath, a month of the Germanic calendar attested by Bede as named after the goddess Ēostre of Anglo-Saxon paganism.[4] Bede describes the worship of Ēostre among the Anglo-Saxons as having died out before the time he was writing. In 1835, Jacob Grimm proposed an equivalent Old High German name, *Ostara, in his work Deutsche Mythologie. An amount of scholarly theory and speculation surrounds the figure. Modern German has Ostern, but otherwise, Germanic languages have generally borrowed the form pascha, see below.

Semitic, Romance, Celtic and other Germanic languages

The Greek word Πάσχα and hence the Latin form Pascha is derived from the Hebrew Pesach (פֶּסַח) meaning the festival of Passover.

Christians speaking Arabic or other Semitic languages generally use names cognate to Pesach. For instance, the second word of the Arabic name of the festival عيد الفصح Template:ArabDIN has the root F-Ṣ-Ḥ, which given the sound laws applicable to Arabic is cognate to Hebrew P-S-Ḥ, with "Ḥ" realized as /x/ in Modern Hebrew and /ħ/ in Arabic. (The Arabic in this regard is more similar to the Biblical Hebrew than the Modern Hebrew pronunciation is). Arabic also uses the term عيد القيامة Template:ArabDIN, meaning "festival of the resurrection," but this term is less common. In Maltese the word is L-Għid. In Ge'ez and the modern Ethiosemitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea, two forms exist: ፋሲካ ("Fasika," fāsīkā) from Greek Pascha, and ትንሣኤ ("Tensae," tinśā'ē), the latter from the Semitic root N-Ś-', meaning "to rise" (cf. Arabic nasha'a - ś merged with "sh" in Arabic and most non-South Semitic languages).

In all Romance languages the name of the Easter festival is derived from the Latin Pascha. In Spanish, Easter is la Pascua, in Italian Pasqua and in Portuguese Páscoa. In French, the name of Easter Pâques also derives from the Latin word but the s following the a has been lost and the two letters have been transformed into a â with a circumflex accent by elide.

In all modern Celtic languages the term for Easter is derived from Latin. In Brythonic languages this has yielded Welsh Pasg, Cornish and Breton Pask. In Goidelic languages the word was borrowed before these languages had re-developed the /p/ sound and as a result the initial /p/ was replaced with /k/. This yielded Irish Cáisc, Gaelic Càisg and Manx Caisht. These terms are normally used with the definite article in Goidelic languages, causing lenition in all cases: An Cháisc, A' Chàisg and Y Chaisht.

In Dutch, Easter is known as pasen and in the Scandinavian languages Easter is known as påske (Danish and Norwegian), påsk (Swedish), páskar (Icelandic) and páskir (Faeroese). The name is derived directly from Hebrew Pesach.[citation needed] The letter å is a double a pronounced /o/, and an alternate spelling is paaske or paask.

Slavic languages

In most Slavic languages, the name for Easter either means "Great Day" or "Great Night". For example, Wielkanoc and Velikonoce mean "Great Night" or "Great Nights" in Polish and Czech, respectively. Великдень (Velykden), Великден (Velikden), and Вялікдзень (Vyalikdzyen') mean "The Great Day" in Ukrainian, Bulgarian, and Belarusian, respectively.

In Croatian and Serbian, however, the day's name reflects a particular theological connection: it is called Uskrs, meaning "Resurrection". In Croatian it is also called Vazam (Vzem or Vuzem in Old Croatian), which is a noun that originated from the Old Church Slavonic verb vzeti (now uzeti in Croatian, meaning "to take"). It also explains the fact that in Serbian Easter is sometimes also called Vaskrs, a liturgical form inherited from the Serbian recension of Church Slavonic. The archaic term Velja noć (velmi: Old Slavic for "great"; noć: "night") was used in Croatian while the term Velikden ("Great Day") was used in Serbian. It is believed that Cyril and Methodius, the "holy brothers" who baptized the Slavic people and translated Christian books from Latin into Old Church Slavonic, invented the word Uskrs from the word krsnuti or "enliven".[citation needed]

Another exception is Russian, in which the name of the feast, Пасха (Paskha), is a borrowing of the Greek form via Old Church Slavonic.[5]

Finno-Ugric languages

In Finnish the name for Easter pääsiäinen, traces back to the Swedish påsk, as does the Sámi word Beassážat. The Hungarian name however, húsvét, literally means the taking of the meat, relating to the end of the Great Lent fasting period. In Estonian it is called Lihavõtted.

Easter in the early Church

The first Christians, Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians, were certainly aware of the Hebrew calendar (Acts 2:1; 12:3; 20:6; 27:9; 1 Cor 16:8), but there is no direct evidence that they celebrated any specifically Christian annual festivals. The observance by Christians of non-Jewish annual festivals is believed by some to be an innovation postdating the Apostolic Age. The ecclesiastical historian Socrates Scholasticus (b. 380) attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of its custom, "just as many other customs have been established," stating that neither Jesus nor his Apostles enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. However, when read in context, this is not a rejection or denigration of the celebration—which, given its currency in Scholasticus' time would be surprising—but is merely part of a defense of the diverse methods for computing its date. Indeed, although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.[6]

Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referencing Easter is a mid-2nd century Paschal homily attributed to Melito of Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.[7] Evidence for another kind of annual Christian festival, the commemoration of martyrs, begins to appear at about the same time as evidence for the celebration of Easter.[8] But while martyrs' "birthdays" were celebrated on fixed dates in the local solar calendar, the date of Easter was fixed by means of the local Jewish lunisolar calendar. This is consistent with the celebration of Easter having entered Christianity during its earliest, Jewish period, but does not leave the question free of doubt.[9]

Second-century controversy

By the later second century, it was accepted that the celebration of Pascha (Easter) was a practice of the disciples and an undisputed tradition. The Quartodeciman controversy, the first of several Paschal/Easter controversies, then arose concerning the date on which Pascha should be celebrated.

The term "Quartodeciman" refers to the practice of celebrating Pascha or Easter beginning on Nisan 14 of the Hebrew calendar, "the LORD's passover" (Leviticus 23:5). According to the church historian Eusebius, the Quartodeciman Polycarp (bishop of Smyrna, by tradition a disciple of John the Evangelist) debated the question with Anicetus (bishop of Rome). The Roman province of Asia was Quartodeciman, while the Roman and Alexandrian churches continued the fast until the Sunday following, wishing to associate Easter with Sunday. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus persuaded the other, but they did not consider the matter schismatic either, parting in peace and leaving the question unsettled.

Controversy arose when Victor, bishop of Rome a generation after Anicetus, attempted to excommunicate Polycrates of Ephesus and all other bishops of Asia for their Quartodecimanism. According to Eusebius, a number of synods were convened to deal with the controversy, which he regarded as all ruling in support of Easter on Sunday.[10] Polycrates (c. 190), however wrote to Victor defending the antiquity of Asian Quartodecimanism. Victor's attempted excommunication was apparently rescinded and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of bishop Irenaeus and others, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent of Anicetus.

These Quartodecimans, or others called by the same name, lingered into the fourth century, when Socrates of Constantinople recorded that some Quartodecimans were deprived of their churches by John Chrysostom[11] and that some were harassed by Nestorius[12].

Third/fourth-century controversy and Council

It is not known how long the Nisan 14 practice continued. But both those who followed the Nisan 14 custom, and those who set Easter to the following Sunday (the Sunday of Unleavened Bread) had in common the custom of consulting their Jewish neighbors to learn when the month of Nisan would fall, and setting their festival accordingly. By the later 3rd century, however, some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with the custom of relying on the Jewish community to determine the date of Easter. The chief complaint was that the Jewish communities sometimes set their week of Unleavened Bread to fall before the spring equinox. Anatolius of Laodicea in the later third century wrote

Those who place [the first lunar month of the year] in [the twelfth zodiacal sign before the spring equinox] and fix the Paschal fourteenth day accordingly, make a great and indeed an extraordinary mistake[13]

Peter, bishop of Alexandria (died 312), had a similar complaint

On the fourteenth day of [the month], being accurately observed after the equinox, the ancients celebrated the Passover, according to the divine command. Whereas the men of the present day now celebrate it before the equinox, and that altogether through negligence and error.[14]

The Sardica paschal table[15] confirms these complaints, for it indicates that the Jews of some eastern Mediterranean city (possibly Antioch) fixed Nisan 14 on March 11 (Julian) in A.D. 328, on March 5 in A.D. 334, on March 2 in A.D. 337, and on March 10 in A.D. 339, all well before the spring equinox.[16]

Because of this dissatisfaction with reliance on the Jewish calendar, some Christians began to experiment with independent computations.[17] Others, however, felt that the customary practice of consulting Jews should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error. A version of the Apostolic Constitutions used by the sect of the Audiani advised:

Do not do your own computations, but instead observe Passover when your brethren from the circumcision do. If they err [in the computation], it is no matter to you....[18]

Two other objections that some Christians may have had to maintaining the custom of consulting the Jewish community in order to determine Easter are implied in Constantine's letter from the Council of Nicea to the absent bishops:

It appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews...For we have it in our power, if we abandon their custom, to prolong the due observance of this ordinance to future ages by a truer order...For their boast is absurd indeed, that it is not in our power without instruction from them to observe these things....Being altogether ignorant of the true adjustment of this question, they sometimes celebrate Passover twice in the same year.[19]

The reference to Passover twice in the same year might refer to the geographical diversity that existed at that time in the Jewish calendar. Jews in one city might compute the Feast of Unleavened Bread differently from Jews in another city.[20] The reference to the Jewish "boast", and, indeed, the strident anti-Jewish tone of the whole passage, suggests another issue: some Christians thought that it was undignified for Christians to depend on Jews to set the date of a Christian festival.

This controversy between those who advocated independent computations, and those who wished to continue the custom of relying on the Jewish calendar, was formally resolved by the First Council of Nicaea in 325 (see below), which endorsed the move to independent computations, effectively requiring the abandonment of the old custom of consulting the Jewish community in those places where it was still used. That the older custom (called "protopaschite" by historians) did not at once die out, but persisted for a time, is indicated by the existence of canons[21] and sermons[22] against it.

Some historians have argued that mid-4th century Roman authorities, in an attempt to enforce the Nicene decision on Easter, attempted to interfere with the Jewish calendar. This theory was developed by S. Liebermann,[23] and is repeated by S. Safrai in the Ben-Sasson History of the Jewish People.[24] This view receives no support, however, in surviving mid-4th century Roman legislation on Jewish matters.[25] The Historian Procopius, in his Secret History,[26] claims that the emperor Justinian attempted to interfere with the Jewish calendar in the 6th century, and a modern writer has suggested[27] that this measure may have been directed against the protopaschites. However, none of Justinian's surviving edicts dealing with Jewish matters is explicitly directed against the Jewish calendar,[28]making the interpretation of Procopius's statement a complex matter.

Date of Easter

| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | April 11 | April 18 |

| 1983 | April 3 | May 8 |

| 1984 | April 22 | |

| 1985 | April 7 | April 14 |

| 1986 | March 30 | May 4 |

| 1987 | April 19 | |

| 1988 | April 3 | April 10 |

| 1989 | March 26 | April 30 |

| 1990 | April 15 | |

| 1991 | March 31 | April 7 |

| 1992 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 1993 | April 11 | April 18 |

| 1994 | April 3 | May 1 |

| 1995 | April 16 | April 23 |

| 1996 | April 7 | April 14 |

| 1997 | March 30 | April 27 |

| 1998 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 1999 | April 4 | April 11 |

| 2000 | April 23 | April 30 |

| 2001 | April 15 | |

| 2002 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2003 | April 20 | April 27 |

| 2004 | April 11 | |

| 2005 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2006 | April 16 | April 23 |

| 2007 | April 8 | |

| 2008 | March 23 | April 27 |

| 2009 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2010 | April 4 | |

| 2011 | April 24 | |

| 2012 | April 8 | April 15 |

| 2013 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2014 | April 20 | |

| 2015 | April 5 | April 12 |

| 2016 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2017 | April 16 | |

| 2018 | April 1 | April 8 |

| 2019 | April 21 | April 28 |

| 2020 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2021 | April 4 | May 2 |

| 2022 | April 17 | April 24 |

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars (both of which follow the cycle of the sun and the seasons). Instead, the date for Easter is determined on a lunisolar calendar, as is the Hebrew calendar.

In Western Christianity, using the Gregorian calendar, Easter always falls on a Sunday between March 22 and April 25 inclusively.[29] The following day, Easter Monday, is a legal holiday in many countries with predominantly Christian traditions. In Eastern Christianity, which use the Julian calendar for religious dating, Easter also falls on a Sunday between March 22 and April 25 inclusive of the Julian calendar. In terms of the Gregorian calendar, due to the 13 day difference between the calendars between 1900 and 2099, these dates are between April 4 and May 8 inclusive.

The precise date of Easter has at times been a matter for contention. At the First Council of Nicaea in 325 it was decided that all Christians would celebrate Easter on the same day, which would be computed independently of any Jewish calculations to determine the date of Passover. It is probable, though, that no method of determining the date was specified by the Council. (No contemporary account of the Council's decisions has survived.) Epiphanius of Salamis wrote in the mid-4th century:

- ...the emperor...convened a council of 318 bishops...in the city of Nicea...They passed certain ecclesiastical canons at the council besides, and at the same time decreed in regard to the Passover that there must be one unanimous concord on the celebration of God's holy and supremely excellent day. For it was variously observed by people....[30]

In the years following the council, the computational system that was worked out by the church of Alexandria came to be normative. It took a while for the Alexandrian rules to be adopted throughout Christian Europe, however. The Church of Rome continued to use an 84-year lunisolar calendar cycle from the late third century until 457. The Church of Rome continued to use its own methods until the 6th century, when it may have adopted the Alexandrian method as converted into the Julian calendar by Dionysius Exiguus (certain proof of this does not exist until the ninth century). Early Christians in Britain and Ireland also used a late third century Roman 84-year cycle until the Synod of Whitby in 664, when they adopted the Alexandrian method. Churches in western continental Europe used a late Roman method until the late 8th century during the reign of Charlemagne, when they finally adopted the Alexandrian method. However, with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by the Catholic Church in 1582 and the continuing use of the Julian calendar by Eastern Orthodox Churches, the date on which Easter is celebrated again deviated, and the discrepancy continues to this day.

Computations

The rule has since the Middle Ages been phrased as Easter is observed on the Sunday after the first full moon on or after the day of the vernal equinox. However, this does not reflect the actual ecclesiastical rules precisely. One reason for this is that the full moon involved (called the Paschal full moon) is not an astronomical full moon, but the 14th day of a calendar lunar month. Another difference is that the astronomical vernal equinox is a natural astronomical phenomenon, which can fall on March 20 or 21, while the ecclesiastical date is fixed by convention on March 21.[31]

In applying the ecclesiastical rules, Christian Churches use March 21 as the starting point in determining the date of Easter, from which they find the next full moon, etc. In the case of Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches, which continue to use the Julian calendar, their starting point in determining the date of Orthodox Easter is also March 21 according to the Julian reckoning, resulting in the divergence in the date of Easter in most years. (see table)

The actual calculations for the date of Easter are somewhat complicated, but can be described briefly as follows:

Easter is determined on the basis of lunisolar cycles. The lunar year consists of 30-day and 29-day lunar months, generally alternating, with an embolismic month added periodically to bring the lunar cycle into line with the solar cycle. In each solar year (January 1 to December 31), the lunar month beginning with an ecclesiastical new moon falling in the 29-day period from March 8 to April 5 inclusive is designated as the Paschal lunar month for that year. Easter is the 3rd Sunday in the Paschal lunar month, or, in other words, the Sunday after the Paschal lunar month's 14th day. The 14th of the Paschal lunar month is designated by convention as the Paschal full moon, although the 14th of the lunar month may differ from the date of the astronomical full moon by up to two days.[32] Since the ecclesiastical new moon falls on a date from March 8 to April 5 inclusive, the Paschal full moon (the 14th of that lunar month) must fall on a date from March 21 to April 18 inclusive.

Accordingly, Gregorian Easter can fall on 35 possible dates - between March 22 and April 25 inclusive[33]. It last fell on March 22 in 1818, and will not do so again until 2285. It fell on March 23 in 2008, but will not do so again until 2160. Easter last fell on the latest possible date, April 25, in 1943 and will next fall on that date in 2038. However, it will fall on April 24, just one day before this latest possible date, in 2011. The cycle of Easter dates repeats after exactly 5,700,000 years, with April 19 being the most common date, happening 220,400 times or 3.9%, compared to the median for all dates of 189,525 times or 3.3%.

To prevent any differences developing in the dating of Easter, the Catholic Church has compiled tables for Easter, which are based on the ecclesiastical rules described above. All affiliated churches celebrate Easter in accordance with these tables.

Relationship to date of Passover

In determining the date of the Gregorian and Julian Easter a lunisolar cycle is followed. In determining the date of the Jewish Passover a lunisolar calendar is also used, and Easter usually falls up to a week after the first day of Passover (Nisan 15 in the Hebrew calendar). However, the differences in the rules between the Hebrew and Gregorian cycles results in Passover falling about a month after Easter in three years of the 19-year cycle. These occur in years 3, 11, and 14 of the Gregorian 19-year cycle (corresponding respectively to years 19, 8, and 11 of the Jewish 19-year cycle).

The reason for the difference is the different scheduling of embolismic months in the two cycles (see computus). In addition, without changes to either calendar, the frequency of monthly divergence between the two festivals will increase over time as a result of the differences in the implicit solar years: the implicit mean solar year of the Hebrew calendar is 365.2468 days while that of the Gregorian calendar is 365.2425 days. In years 2200-2299, for example, the start of Passover will be about a month later than Gregorian Easter in four years out of nineteen.

Since in the modern Hebrew calendar Nisan 15 can never fall on Monday, Wednesday, or Friday, the seder of Nisan 15 never falls on the night of Maundy Thursday. The second seder, observed in some Jewish communities on the second night of Passover can, however, occur on Thursday night.

Because the Julian calendar's implicit solar year has drifted further over the centuries than the those of the Gregorian or Hebrew calendars, Julian Easter is a lunation later than Gregorian Easter in five years out of nineteen, namely years 3, 8,11, 14, and 19 of the Christian cycle. This means that it is a lunation later than Jewish Passover in two years out of nineteen, years 8 and 19 of the Christian cycle. Furthermore, because the Julian calendar's lunar age is now about 4 to 5 days behind the mean lunations, Julian Easter always follows the start of Passover. This cumulative effect of the errors in the Julian calendar's solar year and lunar age has led to the often-repeated, but false, belief that the Julian cycle includes an explicit rule requiring Easter always to follow Jewish Passover.[34]

Reform of the date of Easter

A Pan-Orthodox congress of Eastern Orthodox bishops met in Constantinople in 1923 under the presidency of Patriarch Meletios IV, where the bishops agreed to the Revised Julian calendar. The original form of this calendar would have determined Easter using precise astronomical calculations based on the meridian of Jerusalem.[35][36] However, all the Eastern Orthodox countries that subsequently adopted the Revised Julian calendar adopted only that part of the revised calendar that applied to festivals falling on fixed dates in the Julian calendar. The revised Easter computation that had been part of the original 1923 agreement was never implemented in any Orthodox diocese.

At a summit in Aleppo, Syria, in 1997, the World Council of Churches proposed a reform in the calculation of Easter which would have replaced the present divergent practices of calculating Easter with modern scientific knowledge taking into account actual astronomical instances of the spring equinox and full moon based on the meridian of Jerusalem, while also following the Council of Nicea position of Easter being on the Sunday following the full moon.[37] The WCC presented the following comparative data:

| Year | Astronomical Easter |

Gregorian Easter |

Julian Easter |

Astronomical full moon |

Jewish Passover |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | April 15 | April 15 | April 15 | April 8 | April 8 |

| 2002 | March 31 | March 31 | May 5 | March 28 | March 28 |

| 2003 | April 20 | April 20 | April 27 | April 16 | April 17 |

| 2004 | April 11 | April 11 | April 11 | April 5 | April 6 |

| 2005 | March 27 | March 27 | May 1 | March 25 | April 24 |

| 2006 | April 16 | April 16 | April 23 | April 13 | April 13 |

| 2007 | April 8 | April 8 | April 8 | April 2 | April 3 |

| 2008 | March 23 | March 23 | April 27 | March 21 | April 20 |

| 2009 | April 12 | April 12 | April 19 | April 9 | April 9 |

| 2010 | April 4 | April 4 | April 4 | March 30 | March 30 |

| 2011 | April 24 | April 24 | April 24 | April 18 | April 19 |

| 2012 | April 8 | April 8 | April 15 | April 6 | April 7 |

| 2013 | March 31 | March 31 | May 5 | March 27 | March 26 |

| 2014 | April 20 | April 20 | April 20 | April 15 | April 15 |

| 2015 | April 5 | April 5 | April 12 | April 4 | April 4 |

| 2016 | March 27 | March 27 | May 1 | March 23 | April 23 |

| 2017 | April 16 | April 16 | April 16 | April 11 | April 11 |

| 2018 | April 1 | April 1 | April 8 | March 31 | March 31 |

| 2019 | March 24 | April 21 | April 28 | March 21 | April 20 |

| 2020 | April 12 | April 12 | April 19 | April 8 | April 9 |

Notes: 1. Astronomical Easter is the first Sunday after the Astronomical full moon.

2. Passover commences at sunset preceding the date indicated.

The recommended WCC changes would have side-stepped the calendar issues and eliminated the difference in date between the Eastern and Western churches. The reform was proposed for implementation starting in 2001, but it was not ultimately adopted by any member body.

A few clergymen of various denominations have advanced the notion of disregarding the moon altogether in determining the date of Easter. Their proposals include always observing Easter on the second Sunday in April, or always having seven Sundays between the Epiphany and Ash Wednesday, producing the same result except that in leap years Easter could fall on April 7. These suggestions have not attracted significant support, and their adoption in the future is considered unlikely.

In the United Kingdom, the Easter Act 1928 set out legislation to allow the date of Easter to be fixed as the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April (or, in other words, the Sunday in the period from April 9 to April 15). However, the legislation has not been implemented, although it remains on the Statute book and could be implemented subject to approval by the various Christian churches.[38]

Position in the church year

| Liturgical seasons |

|---|

|

Western Christianity

In Western Christianity, Easter marks the end of Lent, a period of fasting and penitence in preparation for Easter, which begins on Ash Wednesday and lasts forty days (not counting Sundays).

The week before Easter, known as Holy Week, is very special in the Christian tradition. The Sunday before Easter is Palm Sunday and the last three days before Easter are Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday (sometimes referred to as Silent Saturday). Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday and Good Friday respectively commemorate Jesus' entry in Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the Crucifixion. Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday are sometimes referred to as the Easter Triduum (Latin for "Three Days"). In some countries, Easter lasts two days, with the second called "Easter Monday." The week beginning with Easter Sunday is called Easter Week or the Octave of Easter, and each day is prefaced with "Easter", e.g. Easter Monday, Easter Tuesday, etc. Easter Saturday is therefore the Saturday after Easter Sunday. The day before Easter is properly called Holy Saturday. Many churches begin celebrating Easter late in the evening of Holy Saturday at a service called the Easter Vigil.

Eastertide, or Paschaltide, the season of Easter, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts until the day of Pentecost, seven weeks later.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity, the spiritual preparation for Pascha begins with Great Lent, which starts on Clean Monday and lasts for 40 continuous days (including Sundays). The last week of Great Lent (following the fifth Sunday of Great Lent) is called Palm Week, and ends with Lazarus Saturday. The Vespers which begins Lazarus Saturday officially brings Great Lent to a close, although the fast continues through the following week. After Lazarus Saturday comes Palm Sunday, Holy Week, and finally Pascha itself, and the fast is broken immediately after the Paschal Divine Liturgy.

The Paschal Vigil begins with the Midnight Office, which is the last service of the Lenten Triodion and is timed so that it ends a little before midnight on Holy Saturday night. At the stroke of midnight the Paschal celebration itself begins, consisting of Paschal Matins, Paschal Hours, and Paschal Divine Liturgy.[39] Placing the Paschal Divine Liturgy at midnight guarantees that no Divine Liturgy will come earlier in the morning, ensuring its place as the pre-eminent "Feast of Feasts" in the liturgical year.

The liturgical season from Pascha to the Sunday of All Saints (the Sunday after Pentecost) is known as the Pentecostarion (the "fifty days"). The week which begins on Easter Sunday is called Bright Week, during which there is no fasting, even on Wednesday and Friday. The Afterfeast of Pascha lasts 39 days, with its Apodosis (leave-taking) on the day before Ascension. Pentecost Sunday is the fiftieth day from Pascha (counted inclusively).

Although the Pentecostarion ends on the Sunday of All Saints, Pascha's influence continues throughout the following year, determining the daily Epistle and Gospel readings at the Divine Liturgy, the Tone of the Week, and the Matins Gospels all the way through to the next year's Lazarus Saturday.

Religious observance of Easter

Western Christianity

The Easter festival is kept in many different ways among Western Christians. The traditional, liturgical observation of Easter, as practised among Roman Catholics and some Lutherans and Anglicans begins on the night of Holy Saturday with the Easter Vigil. This, the most important liturgy of the year, begins in total darkness with the blessing of the Easter fire, the lighting of the large Paschal candle (symbolic of the Risen Christ) and the chanting of the Exultet or Easter Proclamation attributed to Saint Ambrose of Milan. After this service of light, a number of readings from the Old Testament are read; these tell the stories of creation, the sacrifice of Isaac, the crossing of the Red Sea, and the foretold coming of the Messiah. This part of the service climaxes with the singing of the Gloria and the Alleluia and the proclamation of the Gospel of the resurrection. A sermon may be preached after the gospel. Then the focus moves from the lectern to the font. Anciently, Easter was considered the most perfect time to receive baptism, and this practice is alive in Roman Catholicism, as it is the time when new members are initiated into the Church, and it is being revived in some other circles. Whether there are baptisms at this point or not, it is traditional for the congregation to renew the vows of their baptismal faith. This act is often sealed by the sprinkling of the congregation with holy water from the font. The Catholic sacrament of Confirmation is also celebrated at the Vigil.

The Easter Vigil concludes with the celebration of the Eucharist (or 'Holy Communion'). Certain variations in the Easter Vigil exist: Some churches read the Old Testament lessons before the procession of the Paschal candle, and then read the gospel immediately after the Exsultet. Some churches prefer to keep this vigil very early on the Sunday morning instead of the Saturday night, particularly Protestant churches, to reflect the gospel account of the women coming to the tomb at dawn on the first day of the week. These services are known as the Sunrise service and often occur in outdoor setting such as the church's yard or a nearby park.

The first recorded "Sunrise Service" took place in 1732 among the Single Brethren in the Moravian Congregation at Herrnhut, Saxony, in what is now Germany. Following an all-night vigil they went before dawn to the town graveyard, God's Acre, on the hill above the town, to celebrate the Resurrection among the graves of the departed. This service was repeated the following year by the whole congregation and subsequently spread with the Moravian Missionaries around the world. The most famous "Moravian Sunrise Service" is in the Moravian Settlement Old Salem in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The beautiful setting of the Graveyard, God's Acre, the music of the Brass Choir numbering 500 pieces, and the simplicity of the service attract thousands of visitors each year and has earned for Winston-Salem the soubriquet "the Easter City."

Additional celebrations are usually offered on Easter Sunday itself. Typically these services follow the usual order of Sunday services in a congregation, but also typically incorporate more highly festive elements. The music of the service, in particular, often displays a highly festive tone; the incorporation of brass instruments (trumpets, etc.) to supplement a congregation's usual instrumentation is common. Often a congregation's worship space is decorated with special banners and flowers (such as Easter lilies).

In predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines, the morning of Easter (known in the national language as "Pasko ng Muling Pagkabuhay" or the Pasch of the Resurrection) is marked with joyous celebration, the first being the dawn "Salubong," wherein large statues of Jesus and Mary are brought together to meet, imagining the first reunion of Jesus and his mother Mary after Jesus' Resurrection. This is followed by the joyous Easter Mass.

In Polish culture, The Rezurekcja (Resurrection Procession) is the joyous Easter morning Mass at daybreak when church bells ring out and explosions resound to commemorate Christ rising from the dead. Before the Mass begins at dawn, a festive procession with the Blessed Sacrament carried beneath a canopy encircles the church. As church bells ring out, handbells are vigorously shaken by altar boys, the air is filled with incense and the faithful raise their voices heavenward in a triumphant rendering of age-old Easter hymns. After the Blessed Sacrament is carried around the church and Adoration is complete, the Easter Mass begins. Another Polish Easter tradition is Święconka, the blessing of Easter baskets by the parish priest on Holy Saturday. This custom is celebrated not only in Poland, but also in the United States by Polish-Americans.

Eastern Christianity

Pascha is the fundamental and most important festival of the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches. Every other religious festival on their calendars, including Christmas, is secondary in importance to the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This is reflected in rich Paschal customs in the cultures of countries that have traditionally had an Orthodox Christian majority. Eastern Catholics have similar emphasis in their calendars, and many of their liturgical customs are very similar. This is not to say that Christmas and other elements of the Christian liturgical calendar are ignored. Instead, these events are all seen as necessary but preliminary to, and illuminated by, the full climax of the Resurrection, in which all that has come before reaches fulfilment and fruition. They shine only in the light of the Resurrection. Pascha (Easter) is the primary act that fulfils the purpose of Christ's ministry on earth—to defeat death by dying and to purify and exalt humanity by voluntarily assuming and overcoming human frailty. This is succinctly summarized by the Paschal troparion, sung repeatedly during Pascha until the Apodosis of Pascha, which is the day before Ascension:

- Χριστός Ανέστη εκ νεκρών,

- Θανάτω, θάνατον πατήσας,

- και τοις εν τοις μνήμασι

- ζώην χαρισάμενος!

- Christ is risen from the dead,

- Trampling down death by death,

- And upon those in the tombs

- Bestowing life!

Preparation for Pascha begins with the season of Great Lent. In addition to fasting, almsgiving, and prayer, Orthodox Christians cut down on all entertainment and non-essential worldly activities, gradually eliminating them until Great and Holy Friday, the most austere day of the year. Traditionally, on the evening of Great and Holy Saturday, the Midnight Office is celebrated shortly after 11:00 p.m. (see Paschal Vigil). At its completion all light in the church building is extinguished, and all wait in darkness and silence for the stroke of midnight. Then, a new flame is struck in the altar, or the priest lights his candle from the perpetual lamp kept burning there, and he then lights candles held by deacons or other assistants, who then go to light candles held by the congregation (this practice has its origin in the reception of the Holy Fire at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem). Then the priest and congregation go in a Crucession (procession with the cross) around the temple (church building), holding lit candles, chanting:

Angels in heaven, O Christ our Saviour, praise Thy Resurrection with hymns:

deem us also who are on earth worthy to glorify The with a pure heart.

This procession reenacts the journey of the Myrrhbearers to the Tomb of Jesus "very early in the morning" (Luke 24:1). After circling around the temple once or three times, the procession halts in front of the closed doors. In the Greek practice the priest reads a selection from the Gospel Book (Mark 16:1–8). Then, in all traditions, the priest makes the sign of the cross with the censer in front of the closed doors (which represent the sealed tomb). He and the people chant the Paschal Troparion, and all of the bells and semantra are sounded. Then all re-enter the temple and Paschal Matins begins immediately, followed by the Paschal Hours and then the Paschal Divine Liturgy. After the dismissal of the Liturgy, the priest may bless Paschal eggs and baskets brought by the faithful containing those foods which have been forbidden during the Great Fast.

Immediately after the Liturgy it is customary for the congregation to share a meal, essentially an Agápē dinner (albeit at 2:00 a.m. or later). In Greece the traditional meal is mageiritsa, a hearty stew of chopped lamb liver and wild greens seasoned with egg-and-lemon sauce. Traditionally, Easter eggs, hard-boiled eggs dyed bright red to symbolize the spilt Blood of Christ and the promise of eternal life, are cracked together to celebrate the opening of the Tomb of Christ.

The next morning, Easter Sunday proper, there is no Divine Liturgy, since the Liturgy for that day has already been celebrated. Instead, in the afternoon, it is often traditional to celebrate "Agápē Vespers". In this service, it has become customary during the last few centuries for the priest and members of the congregation to read a portion of the Gospel of John 20:19–25 (in some places the reading is extended to include verses 19:26–31) in as many languages as they can manage, to show the universality of the Resurrection.

For the remainder of the week, known as "Bright Week", all fasting is prohibited, and the customary Paschal greeting is: "Christ is risen!," to which the response is: "Truly He is risen!" This may also be done in many different languages. The services during Bright Week are nearly identical to those on Pascha itself, except that the do not take place at midnight, but at their normal times during the day. The Crucession during Bright Week takes place either after Paschal Matins or the Paschal Divine Liturgy.

Religious and secular Easter traditions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

As with many other Christian dates, the celebration of Easter extends beyond the church. Since its origins, it has been a time of celebration and feasting and many Traditional Easter games and customs developed, such as Egg rolling, Egg tapping, Pace egging and Egg decorating. Today Easter is commercially important, seeing wide sales of greeting cards and confectionery such as chocolate Easter eggs, marshmallow bunnies, Peeps, and jelly beans. Even many non-Christians celebrate these aspects of the holiday while eschewing the religious aspects.

English-speaking world

Throughout North America, New Zealand and Australia the Easter holiday has been partially secularized, so that some families participate only in the attendant revelry, central to which is (traditionally) decorating Easter eggs on Saturday evening and hunting for them Sunday morning, by which time they have been mysteriously hidden all over the house and garden. Chocolate eggs have largely supplanted decorated eggs in New Zealand and Australia.

In North America, parents tell their children that eggs and other treats have been delivered and hidden by the Easter Bunny in an Easter basket which children find waiting for them when they wake up. Many families in America will attend Sunday Mass or services in the morning and then participate in a feast or party in the afternoon.

In the UK children still decorate eggs, but most British people simply exchange chocolate eggs on the Sunday. Chocolate Easter Bunnies can be found in shops. Many families have a traditional Sunday roast, particularly roast lamb, and eat kinds of food like Simnel cake, a fruit cake with eleven marzipan balls representing the eleven faithful apostles. Hot cross buns, spiced buns with a cross on top, are traditionally associated with Good Friday, but today are eaten through Holy Week and the Easter period. In the north of England and the north of Ireland, the traditions of rolling decorated eggs down steep hills and pace egging are still adhered to.

In the British Overseas Territory of Bermuda, the most notable feature of the Easter celebration is the flying of kites to symbolize Christ's ascent.[40] Traditional Bermuda kites are constructed by Bermudians of all ages as Easter approaches, and are normally only flown at Easter. In addition to hot cross buns and Easter eggs, fish cakes are traditionally eaten in Bermuda at this time.

Belgium and France

Flemish-speaking Belgium shares many of the same traditions as North America but sometimes it's said that the Bells of Rome bring the Easter eggs together with the Easter Bunny. The story goes that the bells of every church leave for Rome on Holy Saturday, called "Stille Zaterdag" (literally "Silent Saturday") in Dutch. So, because the bells are in Rome, the bells don't ring anywhere.

Similarly, in French-speaking Belgium and France, "Easter bells" (« les cloches de Pâques ») also bring Easter eggs. However, bells in churches are silent beginning Maundy Thursday, the first day of the Paschal Triduum, as a sign of mourning. It is said that all of the bells depart for Rome and return on Easter Day bringing eggs with them to drop during their passage.

Nordic countries

In Norway, in addition to cross-country skiing in the mountains and painting eggs for decorating, a contemporary tradition is to solve murder mysteries at Easter. All the major television channels show crime and detective stories (such as Agatha Christie's Poirot), magazines print stories where the readers can try to figure out who did it, and many new books are published. Even the milk cartons change to have murder stories on their sides. Another tradition is Yahtzee games.[citation needed]

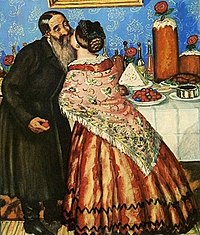

In Finland, Sweden and Denmark, traditions include egg painting and small children dressed as witches collecting candy door-to-door, in exchange for decorated pussy willows. This is a result of the mixing of an old Orthodox tradition (blessing houses with willow branches) and the Scandinavian Easter witch tradition.[citation needed][41] Brightly coloured feathers and little decorations are also attached to birch branches in a vase. For lunch/dinner on Holy Saturday, families traditionally feast on a smörgåsbord of herring, salmon, potatoes, eggs and other kinds of food. In Finland, the Lutheran majority enjoys mämmi as another traditional Easter treat, while the Orthodox minority's traditions include eating pasha (also spelt paskha) instead.

Netherlands and Northern Germany

In the northern and eastern parts of the Netherlands (Twente and Achterhoek), Easter Fires (in Dutch: "Paasvuur") are lit on Easter Day at sunset. Easter Fires also take place on the same day in large portions of Northern Germany ("Osterfeuer").

Central Europe

- Main article: see Egg decorating in Slavic culture

Many eastern European ethnic groups, including the Ukrainians, Belarusians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Croats, Czechs, Lithuanians, Poles, Romanians, Serbs, Macedonians, Slovaks, and Slovenes decorate eggs for Easter.

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, a tradition of spanking or whipping is carried out on Easter Monday. In the morning, men spank women with a special handmade whip called a pomlázka (in Czech) or korbáč (in Slovak), or, in eastern Moravia and Slovakia, throw cold water on them. The pomlázka/korbáč consists of eight, twelve or even twenty-four withies (willow rods), is usually from half a meter to two meters long and decorated with coloured ribbons at the end. The spanking normally is not painful or intended to cause suffering. A legend says that women should be spanked in order to keep their health and beauty during whole next year.[42]

An additional purpose can be for men to exhibit their attraction to women; unvisited women can even feel offended. Traditionally, the spanked woman gives a coloured egg and sometimes a small amount of money to the man as a sign of her thanks. In some regions the women can get revenge in the afternoon or the following day when they can pour a bucket of cold water on any man. The habit slightly varies across Slovakia and the Czech Republic. A similar tradition existed in Poland (where it is called Dyngus Day), but it is now little more than an all-day water fight.

The butter lamb (Baranek wielkanocny) is a traditional addition to the Easter Meal for many Polish Catholics. Butter is shaped into a lamb either by hand or in a lamb-shaped mould.

In Hungary, Transylvania, Southern Slovakia, Kárpátalja, Northern Serbia - Vojvodina and other territories with Hungarian-speaking communities, the day following Easter is called Locsoló Hétfő, "Watering Monday". Water, perfume or perfumed water is often sprinkled in exchange for an Easter egg.

Easter controversies

Christian denominations and organizations that do not observe Easter

Easter traditions deemed "pagan" by some Reformation leaders,[citation needed] along with Christmas celebrations, were among the first casualties of some areas of the Protestant Reformation.

Other Reformation Churches, such as the Lutheran and Anglican, retained a very full observance of the Church Year. In Lutheran Churches, not only were the days of Holy Week observed, but also Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost were observed with three day festivals, including the day itself and the two following. Among the other Reformation traditions, things were a bit different. These holidays were eventually restored (though Christmas only became a legal holiday in Scotland in 1967, after the Church of Scotland finally relaxed its objections). Some Christians (usually, but not always fundamentalists[citation needed]), however, continue to reject the celebration of Easter (and, often, of Christmas), because they believe them to be irrevocably tainted with paganism and idolatry. Their rejection of these traditions is based partly on their interpretation of 2 Corinthians 6:14–16.

This is also the view of Jehovah's Witnesses, who instead observe a yearly commemorative service of the Last Supper and subsequent death of Christ on the evening of Nisan 14, as they calculate it derived from the lunar Hebrew Calendar. It is commonly referred to, in short, by many Witnesses as simply "The Memorial." Jehovah's Witnesses believe that such verses as Luke 22:19–20 and 1 Cor 11:26 constitute a commandment to remember the death of Christ (and not the resurrection, as only the rememberence of the death was observed by early Christians), and they do so on a yearly basis just as Passover is celebrated yearly by the Jews.

Members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) traditionally do not celebrate or observe Easter (or any other Church holidays), believing instead that "every day is the Lord's day", and that elevation of one day above others suggests that it is acceptable to do unChristian acts on other days - they believe that every day is holy, and should be lived as such. This belief of Quakers is known as their testimony against time and season.

Some groups feel that Easter (or, as they prefer to call it, "Resurrection Sunday" or "Resurrection Day") something to be regarded with great joy: not marking the day itself, but remembering and rejoicing in the event it commemorates—the miracle of Christ's resurrection. In this spirit, these Christians teach that each day and all Sabbaths should be kept holy, in Christ's teachings. Hebrew-Christian, Sacred Name, and Armstrong movement churches (such as the Living Church of God) usually reject Easter in favor of Nisan 14 observance and celebration of the Christian Passover. This is especially true of Christian groups that celebrate the New Moons or annual High Sabbaths is addition to the seventh-day Sabbath. This is textually supported by the letter to the Colossians: "Let no one... pass judgment on you in matters of food and drink or with regard to a festival or new moon or sabbath. These are shadows of things to come; the reality belongs to Christ." (Col. 2:16-17, NAB)

Critics charge that such feasts are meaningless in light of the end of the Old Testament sacrificial system and the destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70. Televangelist Larry Huch (Pentecostal) and many Calvary Chapel churches have adopted Hebrew-Christian practices, but without rejecting Easter.

Other seventh-day Sabbatarian groups, such as the Church of God, celebrate a Christian Passover that lacks most of the practices or symbols associated with Western Easter and retains more of the presumed features of the Passover observed by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper.

Modern avoidance controversy

In the modern-day United States, there have been instances where public mention of Easter and Good Friday have been replaced with euphemistic terminology. Examples include renaming "Good Friday" as "Spring holiday" on school calendars, to avoid association with a Christian holiday while at the same time allowing a state-sanctioned day off. (Note that the modern North American "Spring Break" can no longer be assumed to correspond with any version of Easter week.)

References

- ^ Anthony Aveni, "The Easter/Passover Season: Connecting Time's Broken Circle," The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 64-78.

- ^ This resurrection is commonly said to have occurred "on the third day", including the day of crucifixion.

- ^ 'Easter Day' is the traditional name in English for the principal feast of Easter, used (for instance) by the Book of Common Prayer, but in the 20th century 'Easter Sunday' became widely used, despite this term also referring to the following Sunday.

- ^ Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology (1995) ISBN 0062700847

- ^ Max Vasmer, Russisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Heidelberg, 1950-1958.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (2005-07-13). "The Author's Views respecting the Celebration of Easter, Baptism, Fasting, Marriage, the Eucharist, and Other Ecclesiastical Rites" (HTML). Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ^

"Homily on the Pascha" (HTML). Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 474.

- ^ Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 459:"[Easter] is the only feast of the Christian Year that can plausibly claim to go back to apostolic times...[It] must derive from a time when Jewish influence was effective....because it depends on the lunar calendar (every other feast depends on the solar calendar)."

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 5.23.

- ^ Socrates, Church History, 6.11

- ^ Socrates, Church History 7.29

- ^ Eusebius, Church History, 7.32

- ^ Peter of Alexandria, quoted in the Chronicon Paschale. In Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume 14: The Writings of Methodius, Alexander of Lycopolis, Peter of Alexandria, And Several Fragments, Edinburgh, 1869, p. 326.

- ^ MS Verona, Biblioteca Capitolare LX(58) folios 79v-80v.

- ^ Sacha Stern, Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE - Tenth Century CE, Oxford, 2001, pp. 124-132.

- ^ Eusebius reports that Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, proposed an 8-year Easter cycle, and quotes a letter from Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea, that refers to a 19-year cycle. Eusebius, Church History, 7.20, 7.31. An 8-year cycle has been found inscribed on a statue unearthed in Rome in the 17th century, dated to the third century. Allen Brent, Hippolytus and the Roman Church in the Third Century, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1995.

- ^ Epiphanius, Adversus Haereses Heresy 70, 10,1, in Frank Williams, The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Books II and II, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1994, p. 412. Also quoted in Margaret Dunlop Gibson, The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac, London, 1903, p. vii

- ^ Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 3.18, in A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Eerdmans, 1956, p. 54.

- ^ Sacha Stern, Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE - Tenth Century CE, Oxford, 2001, pp. 72-79.

- ^ Apostolic Canon 7: If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon shall celebrate the holy day of Easter before the vernal equinox with the Jews, let him be deposed. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Eerdmans, 1956, p. 594.

- ^ St. John Chrysostom, "Against those who keep the first Passover", in Saint John Chrysostom: Discourses against Judaizing Christians, translated by Paul W. Harkins, Washington, D.C., 1979, p. 47ff.

- ^ S. Liebermann, "Palestine in the 3rd and 4rh Centuries", Jewish Quarterly Review (New Series), 36, p. 334 (1946).

- ^ S. Safrai, "From the Roman Anarchy Until the Abolition of the Patriarchate", in H. H. Ben-Sasson, ed., A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1969 (English trans. 1976), p. 350.

- ^ Amnon Linder, The Jews in Roman Imperial Legislation, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1987. Linder presents only one piece of legislation from the time of Constantine II and one from the time of Constantius II dealing with Jewish matters. Neither has anything do do with the Jewish calendar.

- ^ Procopius, Secret History 28.16-19.

- ^ Sacha Stern, Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE-Tenth Century CE, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001, pp. 85-87.

- ^ Justinian's Novel 146 of A.D. 553 does, however, forbid public reading of the deuterosis, (probably the Mishnah) or expounding of its doctrines. Amnon Linder, The Jews in Roman Imperial Legislation, pp. 402-411.

- ^ The Date of Easter. Article from United States Naval Observatory (March 27, 2007).

- ^ Epiphanius, Adversus Haereses, Heresy 69, 11,1, in Willams, F. (1994). The Panarion of Epiphianus of Salamis Books II and III. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 331.

- ^ Paragraph 7 of Inter gravissimas [1] to "the vernal equinox, which was fixed by the fathers of the [first] Nicene Council at XII calends April [March 21]". This definition can be traced at least back to chapters 6 & 59 of Bede's De temporum ratione (725).

- ^ Montes, Marcos J. "Calculation of the Ecclesiastical Calendar" Retrieved on 2008-01-12

- ^ Easter Sunday always falls after (never on) March 21, so the earliest it can fall is March 22; if the 14th of the Paschal lunar month falls on April 18 and this day is a Sunday, then Easter falls one week (seven days) later on April 25.

- ^ The supposed "after Passover" rule is called the Zonaras proviso, after Joannes Zonaras, the Byzantine canon lawyer who may have been the first to formulate it.

- ^ M. Milankovitch, "Das Ende des julianischen Kalenders und der neue Kalender der orientalischen Kirchen", Astronomische Nachrichten 200, 379–384 (1924).

- ^ Miriam Nancy Shields, "The new calendar of the Eastern churches", Popular Astronomy 32 (1924) 407–411 (page 411). This is a translation of M. Milankovitch, "The end of the Julian calendar and the new calendar of the Eastern churches", Astronomische Nachrichten No. 5279 (1924).

- ^ WCC: Towards a common date for Easter

- ^ See Hansard reports April 2005

- ^ "On the Holy and Great Sunday of Pascha" (HTML). Monastery of Saint Andrew the First Called, Manchester, England. 2007-01-25. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ http://members.chello.nl/h.hagg3/Bermuda_Kite_3.htm Chello.nl: Bermuda Kite History

- ^ Geographia.com accessed March 22, 2008

- ^ Kirby, Terry (2007-04-06). "The Big Question: Why do we celebrate Easter, and where did the bunny come from?" (HTML). The Independent. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

External links

Primary sources

- Bede, De ratione temporum - Extracts referring to Eostre.

Liturgical

- 50 Catholic Prayers for Easter

- Liturgical Resources for Easter

- Holy Pascha: the Resurrection of Our Lord (Orthodox icon and synaxarion)

Traditions

- Christian Festivals - Easter on RE:Quest

- Liturgical Meaning of Holy Week (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia)

- Easter in the Armenian Orthodox Church

- Easter Badarak at the Empty Tomb Easter service in Jerusalem Armenian Apostolic Church

- Eastern Orthodox views on Easter

- Roman Catholic view of Easter (from the Catholic Encyclopedia)

- Rosicrucians: The Cosmic Meaning of Easter (the esoteric Christian tradition)

- Passover to Easter

Calculating

- Calculating the date of Easter

- Calculator for the date of Festivals (Anglican)

- A simple method for determining the date of Easter for all years AD 326 to 4099.

- Paschal Calculator (Eastern Orthodox)

- Orthodox Calculator

- Easter Date Calculator Enter the year you wish to find the Easter day

- One Easter Date Vote for One Date

National traditions

- Easter traditions from around the world

- Easter traditions in Finland

- Easter in Germany

- Easter in Mexico, Australia, Africa and Europe

- World Easter Celebration