Dysautonomia

| Dysautonomia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Autonomic failure, Autonomic dysfunction |

| |

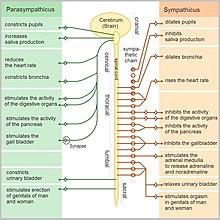

| The autonomic nervous system | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Anhidrosis or hyperhidrosis, blurry vision, tunnel vision, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, diarrhea, dysphagia, bowel incontinence, urinary retention or urinary incontinence, dizziness, brain fog, exercise intolerance, tachycardia, vertigo, weakness and pruritus.[1] |

| Causes | Inadequacy of sympathetic, or parasympathetic, components of autonomic nervous system[2] |

| Risk factors | Alcoholism and diabetes[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Ambulatory blood pressure, as well as EKG monitoring[better source needed][4] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic and supportive[2] |

Dysautonomia, autonomic failure, or autonomic dysfunction is a condition in which the autonomic nervous system (ANS) does not work properly. This may affect the functioning of the heart, bladder, intestines, sweat glands, pupils, and blood vessels. Dysautonomia has many causes, not all of which may be classified as neuropathic.[5] A number of conditions can feature dysautonomia, such as Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, dementia with Lewy bodies,[6] Ehlers–Danlos syndromes,[7] autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy and autonomic neuropathy,[8] HIV/AIDS,[9] mitochondrial cytopathy,[10] pure autonomic failure, autism, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.[11]

Diagnosis is made by functional testing of the ANS, focusing on the affected organ system. Investigations may be performed to identify underlying disease processes that may have led to the development of symptoms or autonomic neuropathy. Symptomatic treatment is available for many symptoms associated with dysautonomia, and some disease processes can be directly treated. Depending on the severity of the dysfunction, dysautonomia can range from being nearly symptomless and transient to disabling and/or life-threatening.[12]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Dysautonomia, a complex set of conditions characterized by autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction, manifests clinically with a diverse array of symptoms, of which postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) stands out as the most common.[11]

The symptoms of dysautonomia, which are numerous and vary widely for each person, are due to inefficient or unbalanced efferent signals sent via both systems.[medical citation needed] Symptoms in people with dysautonomia include:

- Anhydrosis or hyperhidrosis[1]

- Blurry or double vision[1]

- Bowel incontinence[1]

- Brain fog[1]

- Constipation[4]

- Dizziness[4]

- Difficulty swallowing[13]

- Exercise intolerance[1]

- Low blood pressure[4]

- Orthostatic hypotension[1][11]

- Syncope[4]

- Tachycardia[5]

- Tunnel vision[4]

- Urinary incontinence or urinary retention[1]

- Sleep apnea[4]

Causes

[edit]

Dysautonomia may be due to inherited or degenerative neurologic diseases (primary dysautonomia)[5] or injury of the autonomic nervous system from an acquired disorder (secondary dysautonomia).[1][14] Its most common causes include:

- Alcoholism[13][15]

- Amyloidosis[better source needed][4]

- Autoimmune disease, such as Sjögren's syndrome[16][17][18][19] or systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus), and autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy[citation needed]

- Craniocervical instability[13]

- Diabetes[13]

- Eaton-Lambert syndrome[medical citation needed]

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome[20]

- Guillain-Barré syndrome[13][21][22]

- HIV and AIDS[13]

- Long COVID[23][24]

- Multiple sclerosis, meningitis-retention syndrome[13]

- Paraneoplastic syndrome[25]

- Spinal cord injury[13] or traumatic brain injury[26]

- Synucleinopathy, a group of neurodegenerative diseases including pure autonomic failure, Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy[6]

- Surgery or injury involving the nerves[13]

- Toxicity (vincristine)[27]

In the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), predominant dysautonomia is common along with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis, raising the possibility that such dysautonomia could be their common clustering underlying pathogenesis.[28]

In addition to sometimes being a symptom of dysautonomia, anxiety can sometimes physically manifest symptoms resembling autonomic dysfunction.[29][30][31] A thorough investigation ruling out physiological causes is crucial, but in cases where relevant tests are performed and no causes are found or symptoms do not match any known disorders, a primary anxiety disorder is possible but should not be presumed.[32] For such patients, the anxiety sensitivity index may have better predictivity for anxiety disorders, while the Beck Anxiety Inventory may misleadingly suggest anxiety for patients with dysautonomia.[33]

Mitochondrial cytopathies can have autonomic dysfunction manifesting as orthostatic intolerance, sleep-related hypoventilation and arrhythmias.[10][34][35]

Mechanism

[edit]The autonomic nervous system is a component of the peripheral nervous system and comprises two branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS). The SNS controls the more active responses, such as increasing heart rate and blood pressure. The PSNS slows down the heart rate and aids digestion, for example. Symptoms typically arise from abnormal responses of either the sympathetic or parasympathetic systems based on situation or environment.[5][36][26]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Diagnosis of dysautonomia depends on the overall function of three autonomic functions—cardiovagal, adrenergic, and sudomotor. A diagnosis should at a minimum include measurements of blood pressure and heart rate while lying flat and after at least three minutes of standing. The best way to make a diagnosis includes a range of testing, notably an autonomic reflex screen, tilt table test, and testing of the sudomotor response (ESC, QSART or thermoregulatory sweat test).[37]

Additional tests and examinations to diagnose dysautonomia include:

- Ambulatory blood pressure and EKG monitoring[better source needed][4]

- Cold pressor test[37]

- Deep breathing[37]

- Electrochemical skin conductance[citation needed]

- Hyperventilation test[37]

- Nerve biopsy for small fiber neuropathy[1]

- Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART)[37]

- Testing for orthostatic intolerance[37]

- Thermoregulatory sweat test[37][26]

- Tilt table test[37]

- Valsalva maneuver[37][26]

Tests to elucidate the cause of dysautonomia can include:

- Evaluation for acute (intermittent) porphyria[1]

- Evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid by lumbar puncture[1] for infectious/ inflammatory diseases

- Evaluation of nerve conduction study for autonomic neuropathy

- Evaluation of brain and spinal magnetic resonance imaging for myelopathy, stroke and multiple system atrophy

- Evaluation of MIBG myocardial scintigraphy and DaT scan for Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and pure autonomic failure

Vegetative-vascular dystonia

[edit]Particularly in the Russian literature,[38] a subtype of dysautonomia that particularly affects the vascular system has been called vegetative-vascular dystonia.[39] The term "vegetative" reflects an older name for the autonomic nervous system: the vegetative nervous system.[citation needed]

A similar form of this disorder has been historically noticed in various wars, including the Crimean War and American Civil War, and among British troops who colonized India. This disorder was called "irritable heart syndrome" (Da Costa's syndrome) in 1871 by American physician Jacob DaCosta.[40]

Management

[edit]

Treatment of dysautonomia can be difficult; since it is made up of many different symptoms, a combination of drug therapies is often required to manage individual symptomatic complaints. In the case of autoimmune neuropathy, treatment with immunomodulatory therapies is done. If diabetes mellitus is the cause, control of blood glucose is important.[1] Treatment can include proton-pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists used for digestive symptoms such as acid reflux.[41]

To treat genitourinary autonomic neuropathy, medications may include sildenafil (a guanine monophosphate type-5 phosphodiesterase inhibitor). To treat hyperhidrosis, anticholinergic agents such as trihexyphenidyl or scopolamine can be used. Intracutaneous injection of botulinum toxin type A can also be used in some cases.[42]

Balloon angioplasty, a procedure called transvascular autonomic modulation, is specifically not approved in the United States to treat autonomic dysfunction.[43]

In contrast to orthostatic hypotension (OH) in which neurodegenerative diseases might underlie, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) in which psychiatric diseases might underlie responds to psychiatric intervention/ medication, or shows spontaneous remission. [44][45]

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis of dysautonomia depends on several factors; people with chronic, progressive, generalized dysautonomia in the setting of central nervous system degeneration such as Parkinson's disease or multiple system atrophy generally have poorer long-term prognoses. Dysautonomia can be fatal due to pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, or sudden cardiopulmonary arrest.[5] Autonomic dysfunction symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension, gastroparesis, and gustatory sweating are more frequently identified in mortalities.[46]

See also

[edit]- autonomic neuropathy

- Dopamine beta hydroxylase deficiency

- Familial dysautonomia

- Reflex syncope

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Orthostatic intolerance

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Autonomic Neuropathy Clinical Presentation: History, Physical, Causes". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ a b "Dysautonomia Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Dysautonomia | Autonomic Nervous System Disorders | MedlinePlus". NIH. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i [better source needed]"Autonomic Neuropathy. Information about AN. Patient | Patient". Patient info. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ a b c d e "Dysautonomia". NINDS. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ^ a b Palma JA, Kaufmann H (March 2018). "Treatment of autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson disease and other synucleinopathies". Mov Disord (Review). 33 (3): 372–90. doi:10.1002/mds.27344. PMC 5844369. PMID 29508455.

- ^ Castori M, Voermans NC (October 2014). "Neurological manifestations of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome(s): A review". Iranian Journal of Neurology. 13 (4): 190–208. PMC 4300794. PMID 25632331.

- ^ Imamura M, Mukaino A, Takamatsu K, Tsuboi H, Higuchi O, Nakamura H, Abe S, Ando Y, Matsuo H, Nakamura T, Sumida T, Kawakami A, Nakane S (February 2020). "Ganglionic Acetylcholine Receptor Antibodies and Autonomic Dysfunction in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases". Int J Mol Sci (Review). 21 (4): 1332. doi:10.3390/ijms21041332. PMC 7073227. PMID 32079137.

- ^ McIntosh RC (August 2016). "A meta-analysis of HIV and heart rate variability in the era of antiretroviral therapy". Clin Auton Res (Review). 26 (4): 287–94. doi:10.1007/s10286-016-0366-6. PMID 27395409. S2CID 20256879.

- ^ a b Kanjwal K, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, Saeed B, Grubb BP (October 2010). "Autonomic dysfunction presenting as orthostatic intolerance in patients suffering from mitochondrial cytopathy". Clinical Cardiology. 33 (10): 626–629. doi:10.1002/clc.20805. ISSN 1932-8737. PMC 6653231. PMID 20960537.

- ^ a b c Peltier AC (June 2024). "Autonomic Dysfunction from Diagnosis to Treatment". Prim Care. 51 (2): 359–373. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2024.02.006. PMID 38692780.

- ^ Iodice V, Kimpinski K, Vernino S, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA (June 2009). "Efficacy of immunotherapy in seropositive and seronegative putative autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy". Neurology. 72 (23): 2002–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a92b52. PMC 2837591. PMID 19506222.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Autonomic neuropathy

- ^ Kirk KA, Shoykhet M, Jeong JH, Tyler-Kabara EC, Henderson MJ, Bell MJ, Fink EL (August 2012). "Dysautonomia after pediatric brain injury". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 54 (8): 759–64. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04322.x. PMC 3393822. PMID 22712762.

- ^ Tateno F, Sakakibara R, Aiba Y, Ogata T (2020). "Alcoholism mimicking multiple system atrophy: a case report". Clin Auton Res. 30 (6): 581–584. doi:10.1007/s10286-020-00708-y. PMID 32607716. S2CID 220260700.

- ^ Davies K, Ng WF (2021). "Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome". Frontiers in Immunology. 12. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.702505. PMC 8350514. PMID 34381453.

- ^ Imrich R, Alevizos I, Bebris L, Goldstein DS, Holmes CS, Illei GG, Nikolov NP (2015). "Predominant Glandular Cholinergic Dysautonomia in Patients with Primary Sjögren's Syndrome". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 67 (5): 1345–1352. doi:10.1002/art.39044. PMC 4414824. PMID 25622919.

- ^ "Dysautonomia: Malfunctions in Your Body's Automatic Functions".

- ^ "Dysautonomia in Sjögren's". 26 October 2023.

- ^ De Wandele I, Rombaut L, Leybaert L, Van de Borne P, De Backer T, Malfait F, De Paepe A, Calders P (August 2014). "Dysautonomia and its underlying mechanisms in the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 44 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.12.006. PMID 24507822.

- ^ Zaeem Z, Siddiqi ZA, Douglas W, Zochodne DW (2019). "Autonomic involvement in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update". Clin Auton Res. 29 (3): 289–299. doi:10.1007/s10286-018-0542-y. PMID 30019292. S2CID 49868730.

- ^ Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Kuwabara S, Mori M, Ito T, Yamamoto T, Awa Y, Yamaguchi C, Yuki N, Vernino S, Kishi M, Shirai K (2009). "Prevalence and mechanism of bladder dysfunction in Guillain-Barre Syndrome". Neurourol Urodyn. 28 (5): 432–437. doi:10.1002/nau.20663. PMID 19260087. S2CID 25617551.

- ^ Paliwal VK, Garg RK, Gupta A, Tejan N (2020). "Neuromuscular presentations in patients with COVID-19". Neurological Sciences. 41 (11): 3039–3056. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04708-8. PMC 7491599. PMID 32935156.

- ^ Astin R, Banerjee A, Hall CN (2023). "Long COVID: mechanisms, risk factors and recovery". Experimental Physiology. 108 (1): 12–27. doi:10.1113/EP090802. PMC 10103775. PMID 36412084.

- ^ "Paraneoplastic syndromes of the nervous system". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Acob, Lori Mae Yvette. (2021). Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction – Concussion Alliance. Retrieved 21 September 2021, from https://www.concussionalliance.org/autonomic-nervous-system-dysfunction

- ^ Aiba Y, Sakakibara R, Tateno F, Shimizu N (May 2021). "Orthostatic hypotension possibly caused by vincristine". Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (4): 365–366. doi:10.1111/ncn3.12517. S2CID 235628396.

- ^ Martínez-Martínez LA, Mora T, Vargas A, Fuentes-Iniestra M, Martínez-Lavín M (April 2014). "Sympathetic nervous system dysfunction in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis: a review of case-control studies". Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 20 (3): 146–50. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000089. PMID 24662556. S2CID 23799955.

- ^ Soliman K, Sturman S, Sarkar PK, Michael A (2010). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): a diagnostic dilemma". British Journal of Cardiology. 17 (1): 36–9.

- ^ Ackerman K, DiMartini AF (2015). Psychosomatic Medicine. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-19-932931-1.

- ^ Carr A, McNulty M (2016-03-31). The Handbook of Adult Clinical Psychology: An Evidence Based Practice Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-57614-3.

- ^ Tasman A, Kay J, First MB, Lieberman JA, Riba M (2015-03-30). Psychiatry, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ^ Raj V, Haman KL, Raj SR, Byrne D, Blakely RD, Biaggioni I, Robertson D, Shelton RC (March 2009). "Psychiatric profile and attention deficits in postural tachycardia syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 80 (3): 339–44. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.144360. PMC 2758320. PMID 18977825.

- ^ Emanuel H, Ahlstrom K, Mitchell S, McBeth K, Yadav A, Oria CF, Da Costa C, Stark JM, Mosquera RA, Jon C (2021-04-01). "Cardiac arrhythmias associated with volume-assured pressure support mode in a patient with autonomic dysfunction and mitochondrial disease". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 17 (4): 853–857. doi:10.5664/jcsm.9024. ISSN 1550-9397. PMC 8020692. PMID 33231166.

- ^ Parikh S, Gupta A (March 2013). "Autonomic dysfunction in epilepsy and mitochondrial diseases". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 20 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2013.01.003. ISSN 1558-0776. PMID 23465772.

- ^ "Autonomic Nervous System — National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mustafa HI, Fessel JP, Barwise J, Shannon JR, Raj SR, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Robertson D (January 2012). "Dysautonomia: perioperative implications". Anesthesiology. 116 (1): 205–15. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823db712. PMC 3296831. PMID 22143168.

- ^ Loganovsky K (1999). "Vegetative-Vascular Dystonia and Osteoalgetic Syndrome or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome as a Characteristic After-Effect of Radioecological Disaster". Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 7 (3): 3–16. doi:10.1300/J092v07n03_02.

- ^ Ivanova ES, Mukharliamov FI, Razumov AN, Uianaeva AI (2008). "[State-of-the-art corrective and diagnostic technologies in medical rehabilitation of patients with vegetative vascular dystonia]". Voprosy Kurortologii, Fizioterapii, I Lechebnoi Fizicheskoi Kultury (1): 4–7. PMID 18376477.

- ^ Halstead M (2018-01-01). "Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: An Analysis of Cross-Cultural Research, Historical Research, and Patient Narratives of the Diagnostic Experience". Senior Honors Theses & Projects.

- ^ "H2 Blockers. Reducing stomach acid with H2 Blockers. | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ "Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy".

- ^ "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products — Balloon angioplasty devices to treat autonomic dysfunction: FDA Safety Communication — FDA concern over experimental procedures". fda.gov. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Tsuchida T, Ishibashi Y, Inoue Y, et al. (2023). "Treatment of long COVID complicated by postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome-Case series research". J Gen Fam Med. 25 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1002/jgf2.670. PMC 10792321. PMID 38240001.

- ^ Stallkamp Tidd SJ, Nowacki AS, Singh T, et al. (2024). "Comorbid anxiety is associated with more changes in the Management of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 87: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2024.01.003. PMID 38224642. S2CID 266997580.

- ^ Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Freeman R (May 2003). "Diabetic autonomic neuropathy". Diabetes Care. 26 (5): 1553–79. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.5.1553. PMID 12716821.

Further reading

[edit]- Brading A (1999). The autonomic nervous system and its effectors. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-02624-1.

- Goldstein D (2016). Principles of Autonomic Medicine (PDF) (free online version ed.). Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. ISBN 978-0-8247-0408-7.

- Jänig W (2008). Integrative action of the autonomic nervous system : neurobiology of homeostasis (Digitally printed version. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-06754-6.

- Lara A, Damasceno DD, Pires R, Gros R, Gomes ER, Gavioli M, Lima RF, Guimarães D, Lima P, Bueno CR, Vasconcelos A, Roman-Campos D, Menezes CA, Sirvente RA, Salemi VM, Mady C, Caron MG, Ferreira AJ, Brum PC, Resende RR, Cruz JS, Gomez MV, Prado VF, de Almeida AP, Prado MA, Guatimosim S (April 2010). "Dysautonomia due to reduced cholinergic neurotransmission causes cardiac remodeling and heart failure". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 30 (7): 1746–56. doi:10.1128/MCB.00996-09. PMC 2838086. PMID 20123977.

- Schiffer RB, Rao SM, Fogel BS (2003-01-01). Neuropsychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2655-9.