Dunkeld

Dunkeld

| |

|---|---|

Little Dunkeld (nearside of the river) and Dunkeld viewed from the south | |

Location within Perth and Kinross | |

| Population | 1,330 (2022)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NO027425 |

| • Edinburgh | 45 mi (72 km) |

| • London | 376 mi (605 km) |

| Community council |

|

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | DUNKELD |

| Postcode district | PH8 |

| Dialling code | 01350 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

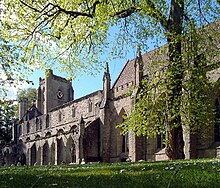

Dunkeld (/dʌŋˈkɛl/, Scots: Dunkell,[2] from Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Chailleann, "fort of the Caledonians"[3]) is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to the geological Highland Boundary Fault, and is frequently described as the "Gateway to the Highlands" due to its position on the main road and rail lines north.[4] Dunkeld has a railway station, Dunkeld & Birnam, on the Highland Main Line, and is about 25 kilometres (15 miles) north of Perth on what is now the A9 road. The main road formerly ran through the town, however following the modernisation of this road it now passes to the west of Dunkeld.[5]

Dunkeld is the location of Dunkeld Cathedral, and is considered to be a remarkably well-preserved example of a Scottish burgh of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.[6] Around twenty of the houses within Dunkeld have been restored by the National Trust for Scotland.[7] The Hermitage, on the western side of the A9, is a countryside property that is also a National Trust for Scotland site.[5][8]

Over the centuries there have been several bridges linking Dunkeld with neighbouring Birnam,[9] and the current bridge, designed by Thomas Telford and financed by the 4th Duke of Atholl, was completed in 1809.[10]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The name Dùn Chailleann means Fort of the Caledonii or of the Caledonians. The 'fort' is presumably the hill fort on King's Seat, slightly north of the town (NO 009 430).[11] Both these place-names imply an early importance for the area of the later town and bishop's seat, stretching back into the Iron Age.

Dunkeld (Duncalden and variants in early documents) is said to have been 'founded' or 'built' by Caustantín son of Fergus, king of the Picts (d. 820).[12] This founding likely referred to one of an ecclesiastical nature on a site already of secular importance, and a Pictish monastery is known to have existed on the site.[13] Kenneth I of Scotland (Cináed mac Ailpín) (843–58) is reputed to have brought relics of St Columba from Iona in 849, in order to preserve them from Viking raids, building a new church to replace the existing structures,[14] which may have been constructed as a simple group of wattle huts. The relics were divided in Kenneth's time between Dunkeld and the Columban monastery at Kells, County Meath, Ireland, to preserve them from Viking raids.[15]

The 'Apostles' Stone', an elaborate but badly worn cross-slab preserved in the cathedral museum, may date to this time.[13] A well-preserved bronze 'Celtic' hand bell, formerly kept in the church of the parish of Little Dunkeld on the south bank of the River Tay opposite Dunkeld, may also survive from the early monastery: a replica is kept in the cathedral museum.[16]

The dedication of the later medieval cathedral was to St Columba. This early church was for a time the chief ecclesiastical site of eastern Scotland (a status yielded in the 10th century to St Andrews). An entry in the Annals of Ulster for 865 refers to the death of Tuathal, son of Artgus, primepscop (Old Irish 'chief bishop') of Fortriu and Abbot of Dunkeld. The monastery was raided in 903 by Danish Vikings sailing up the River Tay, but continued to flourish into the 11th century. At that time, its abbot, Crínán of Dunkeld (d. 1045), married one of the daughters of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (1005–34) and became the ancestor of later Kings of Scots through their son Donnchad (Duncan I) (1034–40).[17]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The see of Dunkeld was revived by Alexander I (1107–24). Between 1183 and 1189 the newly formed diocese of Argyll was separated from that of Dunkeld, which originally extended to the west coast of Scotland.[18] By 1300 the Bishops of Dunkeld administered a diocese comprising sixty parish churches, a number of them oddly scattered within the sees of St Andrews and Dunblane.[19]

The much-restored cathedral choir, still in use as the parish church, is unaisled and dates to the 13th and 14th centuries.[13] The aisled nave was erected from the early 15th century. The western tower, south porch and chapter house (which houses the cathedral museum) were added between 1450 and 1475.[20] The cathedral was stripped of its rich furnishings after the mid-16th century Reformation and its iconoclasm. The nave and porch have been roofless since the early 17th century. They and the tower in the 21st century are in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.[14]

Below the ceiling vault of the tower ground floor are remnants of pre-Reformation murals showing biblical scenes (c. 1490), one of very few such survivals in Scotland. The clearest to survive is a representation of the Judgement of Solomon.[21] This reflects the medieval use of this space as the Bishop's Court. Within the tower are preserved fragments of stonework associated with the cathedral and the surrounding area, including a Pictish carving of a horseman with a spear and drinking-horn, and a number of medieval grave-monuments.[21]

The cathedral museum is housed in the former chapter house and sacristy, on the north side of the choir. After the Reformation this chamber was used as a burial aisle by the Earls, Marquises and Dukes of Atholl, and contains a number of elaborate monuments of the 17th-early 19th centuries.[21]

Battle of Dunkeld (1689)

[edit]Most of the original town was destroyed during the Battle of Dunkeld when, on 21 August 1689,[22] the 26th Foot (Cameronian Regiment), under Lieutenant William Cleland (who died in the clash),[22] successfully fought the Jacobites shortly after the latter's victory at the Battle of Killiecrankie. Holes made by musket-ball strikes during the battle can still be seen in the east gable of the cathedral.[23]

Later history

[edit]Dr George Smyttan FRSE HEIC (1789-1863) was born and raised in Dunkeld and retained links to Birnam all his life.[24]

Dunkeld was partly in the parish of Caputh until 1891.[22]

The High Street drill hall in Dunkeld was completed in 1900.[25]

The alignment of the town was radically altered in 1809 by the building of a new stone bridge — Dunkeld Bridge — over the River Tay by Thomas Telford at the east end of the town, and the laying out of a new street (Bridge Street–Atholl Street) at right angles to the old alignment.[26]

Governance

[edit]Dunkeld is in the Perth and Kinross council area, and in the Community Council area of Dunkeld and Birnam, which also includes Amulree, Butterstone, Dalguise, Kindallachan, Loch Ordie, and Strathbraan.[27][28]

It is in the Perthshire North constituency for the Scottish Parliament where as of 2024[update] has been represented since 2011 by John Swinney for the SNP.[29] It is in the Angus and Perthshire Glens constituency for the UK Parliament, where as of 2024[update] it is represented by Dave Doogan for the SNP.[30][31]

Townscape

[edit]

The rebuilt town of Dunkeld is one of the most complete 18th-century country towns in Scotland. Many of the harled (rough-cast) vernacular buildings have been restored by the National Trust for Scotland (NTS).[7] The present street layout of the older part of town consists of a 'Y-shaped' arrangement, parallel with the River Tay, comprising a single street (Brae Street/High Street) sloping down from the east into the long 'V' of the market place, known as The Cross. Closes (lanes) leading off this main street give access to the backlands of the houses (a traditional arrangement in Scottish towns). On the site of the traditional mercat cross, the fanciful neo-Gothic Atholl Memorial Fountain was built in 1866, as a monument to George Murray, 6th Duke of Atholl (1814–64). The Fountain is notable for its heraldry and Masonic symbolism, the 6th Duke having been Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, 1843–64.[32]

At the west end of The Cross is The Ell Shop (NTS), built 1757, which takes its name from the iron ell (weaver's measure) fixed against one corner. This building is said to have been built on the site of the town's medieval hospital, dedicated to St George. At the north-west corner of the same row is the Duchess of Atholl Girls' School, erected 1853 in neo-Gothic style, designed by R & R Dickson.[33] It is generally known as the Duchess Anne after its founder Anne Home-Drummond (1814–97), spouse of the 6th Duke of Atholl and Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria. The building is used for exhibition and other purposes, notably the popular annual Dunkeld Art Exhibition in summer.[34]

The left arm of the 'Y' leads along Cathedral Street to the medieval cathedral, and the right arm (now largely blocked off) originally led to Dunkeld House, built by Sir William Bruce in 1676-84 for the 1st Marquis of Atholl. Demolished in 1827, this was one of Scotland's major 17th-century mansions. A neo-Gothic replacement was begun on the same site but never completed (no visible remains). The area around the cathedral was the original focus of settlement in Dunkeld in medieval (and doubtless earlier) times. Here stood the manses of the Cathedral clergy, with the Bishop's Palace to the west of the church.[35]

Surrounding countryside

[edit]

Dunkeld is situated in an area of Scotland marketed as Big Tree Country.[36] The area is heavily wooded, and has some notable trees, including the Birnam Oak, believed to be the only remaining tree from the Birnam Wood named by Shakespeare in his play Macbeth:[4]

MACBETH: I will not be afraid of death and bane, till Birnam forest come to Dunsinane.

— Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 5, scene 3.[37]

Other significant trees in the area include Niel Gow's Oak, the tree under which Niel Gow, a fiddler under contract to three of the Dukes of Atholl,[38] composed many of Scotland's famous strathspeys and reels. It stands near Gow's home at Inver. The Parent Larch near Dunkeld cathedral is the sole survivor from a group of larches collected from the mountains of the Tyrol mountains in 1738, and which were the seed source for large-scale larch plantings in the local area.[4]

Much of the countryside surrounding the town is designated as a national scenic area (NSA),[39] one of 40 such areas in Scotland, which are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection by restricting certain forms of development.[40] The River Tay (Dunkeld) NSA covers 5,708 hectares (14,100 acres).[41] Parts of the area also form part of the Tay Forest Park, a network of forests managed by Forestry and Land Scotland that are spread across the Highland parts of Perthshire.[36] About 2 miles (3 kilometres) northeast of the town is the Loch of the Lowes nature reserve, managed by the Scottish Wildlife Trust.[42]

There are many walks in the area.[43] The 1,324 feet (404 m) summit of Birnam Hill (on Murthly Estate) lies 1 mile (2 km) south of the railway station and is easily ascended from there, or from a car park to the east.[44] Newtyle (996 feet (304 m)) and Craigiebarns (900 feet (270 m)) are in the immediate vicinity, while Craig Vinean (1,247 feet (380 m)) is on the opposite side of the river, along with Birnam Hill.[22]

Ossian's Hall of Mirrors is a folly on the pleasure grounds known as The Hermitage, close to Dunkeld. The site is owned by the National Trust for Scotland, and has walks in the wooded scenery surrounding the River Braan.[8]

Tourism and culture

[edit]Its location on the middle section of the River Tay makes it a hub for salmon and trout angling. A few miles downstream at Caputh, Georgina Ballantine landed the largest salmon ever recorded in Britain.[45]

Dunkeld & Birnam Golf Club is located to the north of Dunkeld and overlooks Loch of the Lowes.[46]

Across the Telford Bridge, the Birnam Highland games take place annually in Little Dunkeld.[47]

Transport

[edit]

The A9 through Dunkeld was bypassed by a new section of road in 1977.[48] The town is now approximately one hour from Glasgow and Edinburgh, and two hours from Inverness, by car. There are regular bus and coach services to Birnam and Dunkeld along the A9, with long-distance coaches operated by Scottish Citylink.[49] There is access by rail at Dunkeld & Birnam railway station on the Highland Main Line route between Perth and Inverness. Most services on the route extend to either Edinburgh Waverley or Glasgow Queen Street; on Sundays only a southbound train operated by the East Coast Main Line operator extends to London King's Cross via Edinburgh, although there is no corresponding northbound service from London.[50] A daily (except Saturday) London service is offered by the overnight Caledonian Sleeper trains to and from London Euston.[51]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Scotslanguage.com - Names in Scots - Places in Scotland". www.scotslanguage.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba (AÀA) – Gaelic Place-names of Scotland - Database entry for Dunkeld". Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2010. pp. 127–135. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey, Great Britain (2008), "Blairgowrie & Forest of Alyth", Ordnance Survey Landranger Map (B2 ed.), ISBN 978-0-319-23121-0

- ^ Robin Prentice, ed. (1976). The National Trust for Scotland Guide. Jonathan Cape. p. 271. ISBN 0224012398.

- ^ a b "Dunkeld". National Trust for Scotland. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ a b "The Hermitage". National Trust for Scotland. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Telford's Bridge at Dunkeld". Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "History of Dunkeld and Birnam". Dunkeld and Birnam Tourist Association. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "King's Seat (27172)". Canmore. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Constantine Mac Fergus". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Constantine Mac Fergus". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b c "Dunkeld Cathedral - History". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Dunkeld Cathedral". Historic Environment Scotland. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Five places to view religious relics". Herald Scotland. 23 February 2002. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "The Little Dunkeld Bell" (PDF). Dunkeld Cathedral. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ See Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), South-East Perth, Edinburgh: 1994, 89-90, for a summary of the early history of Dunkeld, and descriptions of the 'Apostles' Stone' and other early sculpture.

- ^ RCAHMS Argyll, Volume 2: Lorn, Edinburgh 1974, 160.

- ^ McNeill, P G B & MacQueen, H L (eds) Atlas of Scottish History to 1707, Edinburgh 1996, 353.

- ^ RCAHMS 1994 (op cit), 124.

- ^ a b c "Dunkeld Cathedral - Statement of Significance". Historic Environment Scotland. 18 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Graphic and Accurate Description of Every Place in Scotland Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Frances Hindes Groome (1901), p. 435

- ^ Inglis, John Alexander. (1911). The Monros of Auchinbowie and Cognate Families. pp. 40 – 44. Edinburgh, Privately printed by T and A Constable. Printers to His Majesty.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Dunkeld, High Street, Scottish Horse Museum". Canmore. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "Dunkeld Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). Perth and Kinross Council. 1 June 2011. p. 4. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "Find your Community Council". Perth & Kinross Council. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

Area 32 - Dunkeld and Birnam

- ^ "Dunkeld & Birnam Community Council". Facebook. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Perthshire North - Scottish Parliament constituency". BBC News. 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Angus and Perthshire Glens - General election results 2024". BBC News. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Angus and Perthshire Glens - MapIt". mapit.mysociety.org. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Denslow, William R. (1957). 10,000 Famous Freemasons. Columbia, Missouri, USA: Missouri Lodge of Research.

- ^ Dictionary of Scottish Architects

- ^ "Dunkeld Art Exhibition". Archived from the original on 21 August 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Dunkeld, Bishop's Palace (27168)". Canmore. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Tay Forest Park: Tall Trees & Big Views" (PDF). Forestry and Land Scotland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Macbeth, Act 5, scene 3". Shakespeare Online. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Niel Gow" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "River Tay (Dunkeld) National Scenic Area". NatureScot. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "National Scenic Areas". NatureScot. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "River Tay (Dunkeld)". Protected Planter. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Loch of the Lowes". Scottish Wildlife Trust. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Dunkeld & Birnam Walking & Cycling". Dunkeld & Birnam Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Birnam Hill, Birnam". Walkhighlands. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Georgina Ballantine | Canal & River Trust". canalrivertrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "The Course". dunkeldgolf. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Birnam Highland Games". birnamhighlandgames.com. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Thomas Telford's Bridge". Dunkeld & Birnam Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Timetable:Edinburgh/Inverness" (PDF). Scottish CityLink Coaches Ltd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Timetable: Edinburgh & Glasgow - Inverness (20 May 2018 – 8 Dec 2018)" (PDF). ScotRail. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Timetable: London - Inverness (20 May 2018 – 8 Dec 2018)". Caledonian Sleeper. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- Dunkeld and Birnam Tourist Association

- Dunkeld & Birnam at VisitScotland Perthshire

- Engraving of a view of Dunkeld by James Fittler in the digitised copy of Scotia Depicta, or the antiquities, castles, public buildings, noblemen and gentlemen's seats, cities, towns and picturesque scenery of Scotland, 1804 at National Library of Scotland

- Engraving of Dunkeld in 1693 by John Slezer at National Library of Scotland

- Dunkeld House Tree Trail - Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust

- Explore the Dunkeld Path Network - Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust