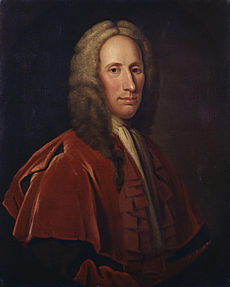

Duncan Forbes of Culloden (judge, born 1685)

Duncan Forbes of Culloden | |

|---|---|

Duncan Forbes of Culloden | |

| Lord President of the Court of Session | |

| In office 20 June 1737 – 4 June 1748 | |

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | Hew Dalrymple, Lord North Berwick |

| Succeeded by | Robert Dundas of Arniston |

| Lord Advocate | |

| In office 1725–1737 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Dundas of Arniston |

| Succeeded by | Charles Erskine |

| MP for Ayr Burghs | |

| In office 1721–1722 | |

| MP for Inverness Burghs | |

| In office 1722–1737 | |

| Sheriff of Edinburgh-shire | |

| In office 1716–1725 | |

| Deputy lieutenant, Inverness-shire | |

| In office 1715–1716 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 November 1685 Culloden House, Inverness, Scotland |

| Died | 10 December 1747 (aged 62) Edinburgh |

| Resting place | Greyfriars Kirkyard |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse | Hon. Mary Rose (c.1690–1717?) |

| Children | Elizabeth Forbes John Forbes (1710–1772) |

| Parent(s) | Duncan Forbes of Culloden (1644–1704) Mary Innes |

| Residence | Culloden House |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen University of Edinburgh Leyden University |

| Occupation | Lawyer and politician |

Duncan Forbes 5th of Culloden (10 November 1685 – 10 December 1747) was a Scottish lawyer and Whig politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1721 to 1737. As Lord President and senior Scottish legal officer, he played a major role in helping the government suppress the 1745 Jacobite Rising.

Life

[edit]

Duncan Forbes was born on 10 November 1685, in Culloden House near Inverness, second son of Duncan Forbes (1644-1704) and his wife Mary Innes (ca 1650–1716). The fifth of nine children, he had seven sisters; Jean (ca 1678-?) and Margaret both married, while little is known of the others.[3] His elder brother, John (1673-1734), was 12 years older; despite the age difference, the two were close friends all their lives.[4]

Forbes was educated at the local grammar school before progressing to Marischal College, Aberdeen in 1699.[5] After briefly attending the University of Edinburgh in 1705, he completed his legal studies at Leyden University in the Netherlands.[6]

He returned home in 1707 and in October 1708 married Mary Rose (1690-before 1717), daughter of Hugh Rose, 15th of Kilravock, whose family owned nearby Kilravock Castle. Forbes inherited the Culloden estates when his elder brother died childless in 1734 and these later passed to his son John (1710-1772).

Career

[edit]

The 1707 Union combined Scotland and England into the Kingdom of Great Britain but the two countries retained separate legal systems. Reconciling the two led to an increase in legal work; Forbes was admitted to the Scottish Faculty of Advocates on 26 July 1709, a professional body with less than 200 members in 1714.[7]

Like their father, the Forbes and their associates were political allies of John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll; from 1713 to 1727, John Forbes was MP for Inverness-shire, then Nairnshire, both controlled by Argyll.[8] Other members of this circle included Duncan's brother-in-law Hugh Rose and his cousin George (1685-1765), who from 1741 to 1747 was MP for Ayr Burghs, another constituency controlled by Argyll.[9]

In 1714, Forbes was appointed Sheriff-depute for Edinburghshire and Deputy lieutenant for Inverness-shire. During the Jacobite Rising of 1715, his patron Argyll was government commander in Scotland; the Forbes brothers raised a number of independent companies and fortified Culloden and Kilvarock. They joined forces with Lord Lovat and captured Inverness, just before the Rising ended at the Battle of Sheriffmuir. In recognition of his services, Forbes was made Depute-Advocate in March 1716.[4]

This required him to prosecute Jacobite prisoners, many of whom had been moved to Carlisle for trial. Forbes considered this unfair, as it was contrary to the accepted practice they be tried in the counties where the actions were alleged to have taken place. He allegedly collected money for their support and also wrote to Sir Robert Walpole recommending clemency, which led to accusations he was pro-Jacobite.[10] This did not affect his career and in 1721, he became MP for Ayr Burghs; in 1722, he was elected for Inverness Burghs, which he held until 1737.[11]

Forbes was appointed Lord Advocate in 1725, an office increased in importance by the suspension and later abolition of the position of Secretary of State. He was almost immediately involved in the 1725 malt tax riots, caused by protests against a new tax that increased the price of beer.[a] These affected many cities, the largest in Glasgow, where rioters sacked the house of Daniel Campbell, MP for Glasgow or Clyde Burghs, who voted for the tax in Parliament.[12] Forbes ordered the arrest of several Glasgow magistrates suspected of inciting the unrest; they were soon released and the government made a number of concessions, although Daniel Campbell was awarded £6,080 in compensation.

Following the 1737 Porteous Riots in Edinburgh, a bill was introduced in Parliament imposing penalties on the city, which was opposed by Argyll and Scots MPs in the Commons, Forbes included.[b] His speeches of 16 May and 9 June on this topic were his last in Parliament; on 21 June, he resigned as an MP and took up the position of Lord President of the Court of Session, becoming the senior legal officer in Scotland.

Role during the 1745 Rebellion

[edit]

The failure of the 1719 Rising meant many Jacobites viewed the Stuart cause as hopeless and sought to return home.[13] Pardoning them worked for the government, since it was clear the Highlands could not be governed without the co-operation of the clan chiefs. [14] In addition, sales of confiscated property were either delayed by legal arguments or reduced by fictitious debts, with former rebels often aided in this process by their loyalist friends and neighbours. This built links of obligation and friendship between the two sides and explains the bitterness displayed after 1745 towards those like Lord George Murray, pardoned for their roles in 1715 and 1719.[15]

Although many Scots remained opposed to the 1707 Union and the malt tax and Porteous riots showed a lack of sensitivity by the London government, these were minor issues; Glasgow, centre of the 1725 protests, remained resolutely anti-Jacobite in 1745. In March 1743, the Highland-recruited 42nd Regiment or Black Watch was posted to Flanders to fight in the War of the Austrian Succession, despite Forbes warning this was contrary to an understanding their service was restricted to Scotland. A short-lived mutiny was suppressed and the regiment gained an impressive fighting record during the next few years.[16]

By 1737, the exiled Stuart claimant James Francis Edward was reportedly 'living quietly in Rome, having abandoned all hope of a restoration.'[17] This changed in 1740 after the war placed Britain and France on opposing sides; Louis XV proposed a landing in England in early 1744 to restore the Stuarts, primarily to divert British resources from Flanders. As demonstrated in 1708 and 1719, threatening an invasion was far more cost effective than an actual one and the plan was abandoned after the French fleet was severely damaged by winter storms in March.[18]

In August 1744, Prince Charles met Jacobite agent Murray of Broughton in Paris, telling him he was "determined to come to Scotland ...though with a single footman".[19] His arrival on Eriskay on 23 July took both sides by surprise; even then, "the cold reality [is] that he was unwanted and unwelcomed". [20] Despite being urged to return to France immediately, enough Scots were eventually persuaded and the 1745 Rising launched on 19 August.[21]

Forbes received confirmation of the landing on 9 August, which he forwarded to London.[22] The military commander in Scotland Sir John Cope had only 3,000 soldiers available, many untrained recruits and initially could do little to suppress the rebellion. Forbes instead used personal relationships to keep people loyal and though unsuccessful with some, many others stayed on the sidelines as a result.[23] His efforts were recognised by both sides; a Jacobite commentator later wrote that 'had the Lord President been as firm a friend of the Stuarts as he was an opponent,...we should have seen an army of 18,000, not 5,000 invade England.'[24]

After the Jacobite entry into Edinburgh and their victory at Prestonpans in September, Forbes and John Campbell, Earl of Loudoun based themselves in Inverness with around 2,000 recruits, sending regular updates to General George Wade in Newcastle.[25] Acting on instructions from Lovat, the Frasers attempted to kidnap Forbes in October, then attacked Fort Augustus in December; Lovat was arrested but escaped without difficulty in early January.[26] [c] Forbes and Loudon relocated to the Isle of Skye in early February after the Jacobites abandoned the siege of Stirling Castle and retreated to Inverness.

After the Battle of Culloden in April ended the Rising, Forbes supported severe penalties for the leaders, especially repeat offenders like Murray and Lovat but counselled 'Unnecessary Severitys create Pity.'[27] He opposed the 1746 Dress Act banning Highland attire, arguing enforcement of the 1716 Disarming Act was more important. This advice was largely ignored by Cumberland, who wrote ...he is Highland mad...and believes once dispersed, the rebels are no more consequence than a London mob.[28] When Flora MacDonald was arrested and sent to London for helping Charles escape, Forbes arranged for her to be held in a private residence until released by the Act of Indemnity in June 1747.[29]

Forbes was financially ruined by the Rising; his estate was badly damaged during the battle, while he was never reimbursed for the monies spent on behalf of the government.[30] He died on 10 December 1747 and was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard, near to his brother John. The grave lies south of the church and is marked by a stone slab added in the 1930s by the Saltire Society. A statue of him by Louis-François Roubiliac was erected in the Parliament House, Edinburgh by the Faculty of Advocates in 1752.

Legacy

[edit]

In 1690, his father was granted the right to distil whisky in the barony of Ferintosh without being subject to the normal excise regulations.[31] His son John married his cousin Jean in 1749 and restored the family fortunes by enlarging an existing distillery at Ferintosh and building three more.[32]

Forbes wrote a number of theological works, including A Letter to a Bishop, concerning some important Discoveries in Religion and Theology, Some Thoughts concerning Religion, natural and revealed … tending to show that Christianity is, indeed, very near as old as the Creation, and Reflections on the Sources of Incredulity with respect to Religion. He campaigned against the 'excessive use of tea,' claiming it threatened the commercial prosperity of the country and wanted to limit its use to those with an income under £50 a year.

A keen golfer, he was a founder of the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith and despite his strict Presbyterianism, a friend and tenant of Francis Charteris. A notorious sexual predator and gambler who became extremely wealthy from the 1720 South Sea bubble, Charteris allegedly appears in William Hogarth's paintings, A Rake's Progress and A Harlot's Progress (see Plate). Accused of rape for the third time in 1730, he was sentenced to death; the Earl of Egmont wrote in his diary All the world agree he deserved to be hanged long ago, but they differ whether on this occasion. Fog's Weekly Journal of 14 March 1730 reported No Rapes have been committed for three Weeks past. Colonel Francis Charteris is still in Newgate. Forbes acted as his lawyer and is said to have been instrumental in obtaining a pardon; Charteris left him £1000 when he died in 1732. [33]

He enjoyed playing golf in the snow on Leith Links and was subject of the humorous poem "The Goff" by Rev Thomas Mathieson of Brechin. In 1744 he competed unsuccessfully against Hew Dalrymple, Lord Hailes and others for the silver golf club awarded by Edinburgh Town Council as a prize for the best golfer.[34]

In Fiction

[edit]Duncan Forbes of Culloden is mentioned in Robert Louis Stevenson, Catriona (1893), the sequel to Kidnapped. He features as a character in Neil Munro's novel, The New Road (1914) and Naomi Mitchison's novel, The Bull Calves (1947).

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This was a wider issue than it may appear; lack of clean drinking water, particularly in cities, meant it was often replaced by low-alcohol or small beer, since the fermentation process made it safer.

- ^ The Riots form the centrepiece of Walters Scott's 1818 novel The Heart of Midlothian

- ^ Lovat referred to Forbes as ‘the upstart offspring of a servant of Strehines and a burgher of Inverness, that no man in his senses can call a family, no more than a mushroom of one night’s growth can be called an old oak tree of five hundred years’ standing.'

References

[edit]- ^ "Addressing a Judge". The Scottish Courts & Tribunal Service. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Paul, James Balfour (1903). An Ordinary of Arms Contained in the Public Register of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Edinburgh: W. Green & sons. p. 74.

- ^ "Duncan Forbes, 3rd of Culloden". Clan Macfarlane Genealogy. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ a b Shaw 2008, p. Oxford DNB.

- ^ PJ, Anderson. "Studies in the History of the University of Aberdeen" (PDF). Electric Scotland. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Baston 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Houston 2017, p. 681.

- ^ Sedgwick 1970, p. FORBES, John (c.1673-1734).

- ^ Sedgwick 1970, p. FORBES, George (1685-1765).

- ^ Duff 1815, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Sedgwick 1970, p. FORBES, Duncan (1685-1747), of Edinburgh.

- ^ Sedgwick 1970, p. CAMPBELL, Daniel (1672-1753), of Shawfield, Lanark, and Ardentenie and Islay, Argyll.

- ^ Lenman 1980, p. 195.

- ^ Szechi & Sankey 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Szechi & Sankey 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Groves 1893, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Blaikie 1916, p. 57.

- ^ Harding 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Murray 1898, p. 93.

- ^ Duke 1927, p. 66.

- ^ Duffy 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Scobie 1941, p. 8.

- ^ "Letter from Lord Loudon and Duncan Forbes [of Culloden] (Lord President) to Field Marshall Wade 13 November 1745". Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Fraser 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Duff 1815, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 460.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 496.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 497–498.

- ^ Du Toit 2004.

- ^ "An 18th century distillery at Mulchaich Farm, Ferintosh on the Black Isle, Ross-shire". North of Scotland Archaeological Society. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Life 2008, p. Charteris, Francis (c. 1665–1732).

- ^ Cassell's Old and New Edinburgh; vol. 6, p. 262

Sources

[edit]- Baston, Karen (2016). Charles Areskine's Library: Lawyers and Their Books at the Dawn of the Scottish Enlightenment. Brill. ISBN 978-9004315372.

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1916). Origins of the 'Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising. T. and A. Constable at the Edinburgh University Press for the Scottish History Society. OCLC 2974999 – via Internet Archive.

- Duff, HR (1815). Culloden papers: comprising an extensive and interesting correspondence from the year 1625 to 1748;. Andesite Press. ISBN 978-1375680790.

- Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Untold Story of the Jacobite Rising (First ed.). Orion. ISBN 978-0304355259.

- Duke, Winifred (1927). Lord George Murray and the Forty-five (First ed.). Milne & Hutchison.

- Du Toit, Alexandre (2004). "Forbes, Duncan (b. in or after 1643, d. 1704)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9821. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander. Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel and Double Agent. Harper Collins.

- Groves, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729–1893. W. & A. K. Johnston. ISBN 978-1376269482.

- Harding, Richard (2013). The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739–1748. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843838234.

- Houston, Robert A (2017). "Law & Literature in Scotland, c 1450 to 1707". In Hutson, Lorna (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of English Law and Literature, 1500-1700. OUP. ISBN 978-0199660889.

- Lenman, Bruce (1980). The Jacobite Risings in Britain 1689–1746. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0413396501.

- Life, Page (2008). Charteris, Francis (c. 1665–1732). Oxford DNB. ISBN 978-0199562442.

- Murray, John (1898). Bell, Robert Fitzroy (ed.). Memorials of John Murray of Broughton: Sometime Secretary to Prince Charles Edward, 1740-1747. T. and A. Constable at the Edinburgh University Press for the Scottish History Society. OCLC 879747289 – via Internet Archive.

- Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- Scobie, IH Mackay (1941). "The Highland Independent Companies 1745-1747". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 20 (77): 5–37. JSTOR 44219908.

- Sedgwick, R, ed. (1970). FORBES, John (c.1673-1734), of Culloden, Inverness (Online ed.). Boydell & Brewer.

- Shaw, John S (2008). "Forbes, Duncan (1685-1747)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9822. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Szechi, Daniel; Sankey, Margaret (November 2001). "Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745". Past & Present (173): 90–128. doi:10.1093/past/173.1.90. JSTOR 3600841.

External links

[edit]- "Duncan Forbes, 3rd of Culloden". Clan Macfarlane Genealogy. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- PJ, Anderson. "Studies in the History of the University of Aberdeen" (PDF). Electric Scotland. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "An 18th century distillery at Mulchaich Farm, Ferintosh on the Black Isle, Ross-shire". North of Scotland Archaeological Society. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Letter from Lord Loudon and Duncan Forbes [of Culloden] (Lord President) to Field Marshall Wade 13 November 1745". Cumbria Archive and Local Studies Centre.

- A Letter from a Fyfe Gentleman, at present in Edinburgh, to the Chief Magistrate of a Burgh in Fyfe, Upon the present Situation, with regard to the Malt-Tax, By the Author of a former Letter from Fyfe upon the same Subject, dated 31 December 1724. Millar’s uncertainty over whether the material he sent constituted a “pamphlet” might imply that A Letter was meant to be supplemented by further pamphlets by the same author.[1]

- ^ "Letter from Andrew Millar to Robert Wodrow, 5 August, 1725". www.millar-project.ed.ac.uk.

- 1685 births

- 1747 deaths

- Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Scottish constituencies

- Lord Advocates

- Senators of the College of Justice

- Members of the Faculty of Advocates

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Leiden University alumni

- Deputy lieutenants of Inverness-shire

- Lords President of the Court of Session

- British MPs 1715–1722

- British MPs 1722–1727

- British MPs 1727–1734

- British MPs 1734–1741

- Burials at Greyfriars Kirkyard

- Scottish male golfers

- Alumni of the University of Aberdeen