Duccio

Duccio | |

|---|---|

Maestà detail of Madonna and Child on throne | |

| Born | Duccio di Buoninsegna c. 1255–1260 |

| Died | c. 1318–1319 (aged 57–64) Siena, Republic of Siena |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Rucellai Madonna (1285), Maestà (1308–1311) |

| Movement | Sienese school, Gothic Style |

Duccio di Buoninsegna (UK: /ˈduːtʃioʊ/ DOO-chee-oh,[1] Italian: [ˈduttʃo di ˌbwɔninˈseɲɲa]; c. 1255–1260 – c. 1318–1319), commonly known as just Duccio, was an Italian painter active in Siena, Tuscany, in the late 13th and early 14th century. He was hired throughout his life to complete many important works in government and religious buildings around Italy. Duccio is considered one of the greatest Italian painters of the Middle Ages,[2] and is credited with creating the painting styles of Trecento and the Sienese school. He also contributed significantly to the Sienese Gothic style.

Biography

[edit]Although much is still unconfirmed about Duccio and his life, there is more documentation of him and his life than of other Italian painters of his time. It is known that he was born and died in the city of Siena, and was also mostly active in the surrounding region of Tuscany. Other details of his early life and family are as uncertain, as much else in his history.

One avenue to reconstructing Duccio's biography are the traces of him in archives that list when he ran up debts or incurred fines. Some records say he was married with seven children. The relative abundance of archival mentions has led historians to believe that he had difficulties managing his life and his money. Due to his debts, Duccio's family dissociated themselves from him after his death.[3]

Another route to filling in Duccio's biography is by analyzing the works that can be attributed to him with certainty. Information can be obtained by analyzing his style, the date and location of the works, and more. Due to gaps where Duccio's name goes unmentioned in the Sienese records for years at a time, scholars speculate he may have traveled to Paris, Assisi and Rome.[4]

Nevertheless, his artistic talents were enough to overshadow his lack of organization as a citizen, and he became famous in his own lifetime. In the 14th century Duccio became one of the most favored and radical painters in Siena.

Artistic career

[edit]

Where Duccio studied, and with whom, is still a matter of great debate, but by analyzing his style and technique art historians have been able to limit the field.[5] Many believe that he studied under Cimabue, while others think that maybe he had actually traveled to Constantinople himself and learned directly from a Byzantine master.

Little is known of his painting career prior to 1278, when at the age of 23 he is recorded as having painted twelve account book cases.[6] Although Duccio was active from 1268 to about 1311 only approximately 13 of his works survive today.[7]

Of Duccio's surviving works, only two can be definitively dated. Both were major public commissions:[8] the "Rucellai Madonna" (Galleria degli Uffizi), commissioned in April 1285 by the Compagnia del Laudesi di Maria Vergine for a chapel in Santa Maria Novella in Florence; and the Maestà commissioned for the high altar of Siena Cathedral in 1308, which Duccio completed by June 1311.[9]

Style

[edit]

Duccio's known works are on wood panel, painted in egg tempera and embellished with gold leaf. Differently from his contemporaries and artists before him, Duccio was a master of tempera and managed to conquer the medium with delicacy and precision. There is no clear evidence that Duccio painted frescoes.[5]

Duccio's style was similar to Byzantine art in some ways, with its gold backgrounds and familiar religious scenes; however, it was also different and more experimental. Duccio began to break down the sharp lines of Byzantine art, and soften the figures. He used modeling (playing with light and dark colors) to reveal the figures underneath the heavy drapery; hands, faces, and feet became more rounded and three-dimensional. Duccio's paintings are inviting and warm with color. His pieces consisted of many delicate details and were sometimes inlaid with jewels or ornamental fabrics. Duccio was also noted for his complex organization of space. He organized his characters specifically and purposefully. In his "Rucellai Madonna" (c. 1285) the viewer can see all of these qualities at play.[10]

Duccio was also one of the first painters to put figures in architectural settings, as he began to explore and investigate depth and space. He also had a refined attention to emotion not seen in other painters at this time. The characters interact tenderly with each other; it is no longer Christ and the Virgin, it is mother and child. He flirts with naturalism, but his paintings are still awe inspiring. Duccio's figures seem to be otherworldly or heavenly, consisting of beautiful colors, soft hair, gracefulness and fabrics not available to mere humans.

He influenced many other painters, most notably Simone Martini, and the brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti.

Followers

[edit]In the course of his life, Duccio had many pupils even if it is not known if they were true pupils who were formed and matured artistically within his workshop, or they were simply painters who imitated his style. Many of the artists are anonymous, and their connection to Duccio has emerged only from analysis of a body of work with common stylistic traits. The first pupils, who can be referred to as a group as first-generation followers, were active between about 1290 and 1320 and include the Master of Badia a Isola, the Master of Città di Castello, the Aringhieri Master, the Master of the Collazioni dei Santi Padri and the Master of San Polo in Rosso.

Another group of followers, who could be termed followers of the second generation, were active between about 1300 and 1335 and include Segna di Bonaventura, Ugolino di Nerio, the Master of the Gondi Maestà, the Master of Monte Oliveto and the Master of Monterotondo. It should, however, be said that Segna di Bonaventura was already active prior to 1300 and so he overlaps as to period both the first and second generation of followers.

A third group followed Duccio only several years after his death, which shows the impact his painting had on Siena and on Tuscany as a whole. The artists of this third group, active between about 1330 and 1350, include Segna di Bonaventura's sons, that is, Niccolò di Segna and Francesco di Segna, and a pupil of Ugolino di Nerio: the Master of Chianciano.

Some of the artists were influenced by Duccio alone to the point of creating a decided affinity or kinship between their works and his. Among them was the Master of Badia a Isola, and Ugolino di Nerio, along with Segna di Bonaventura and their sons. Other artists were influenced also by other schools, and these include the Aringhieri Master (think of the massive volumes of Giotto), and the Master of the Gondi Maestà (who shows the influence also of Simone Martini).

The case of Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti is somewhat different. Both artists painted works that have affinities with Duccio: for Simone from about 1305, and Pietro from about 1310 onwards. However, from the outset their work showed distinctive individual features, as can be seen in Simone's Madonna and Child no. 583 (1305–1310) and in Pietro's Orsini Triptych, painted at Assisi (about 1310–1315). Later the two developed styles with completely independent characteristics such that they acquired an artistic standing that elevates them well beyond being labelled simply as followers of Duccio.

Exhibitions

[edit]Many of Duccio’s surviving paintings were displayed in the 2024-25 exhibit Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery London, alongside those of brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Simone Martini, and other Sienese masters of the era.[11][12] The exhibit was judged “the must-see art show of the season.”[13][14]

Gallery

[edit]-

Annunciation

-

Transfiguration

-

Crucifixion Triptych

-

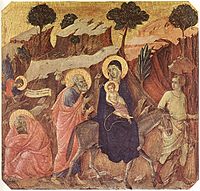

Flight into Egypt

-

The Raising of Lazarus

-

Christ and the Samaritan Woman

-

Maestà, detail

-

Christ before Caiaphas

Known surviving works

[edit]

- Madonna with Child – Tempera and gold on wood, Museo d'Arte Sacra della Val d'Arbia, Buonconvento, near Siena

- Gualino Madonna – Tempera and gold on wood, Galleria Sabauda, Turin

- Madonna with Child and two Angels (Also known as the Crevole Madonna; c. 1280) – Tempera and gold on wood, Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana, Siena

- Madonna with Child enthroned and six Angels (c. 1285) – Also known as the Rucellai Madonna / Madonna Rucellai – Tempera and gold on wood, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy (on deposit from Santa Maria Novella)

- Crucifix – Tempera on wood, Odescalchi Collection, Rome, formerly in the Castello Orsini at Bracciano

- Crucifix (Grosseto) (1289) – Church of San Francesco, Grosseto

- Madonna of the Franciscans (c. 1300) – Tempera and gold on wood, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

- Triptych: Crucifixion and other Scenes c. 1302–08 Royal Collection Trust[15]

- Assumption and Crowning of the Virgin – Stained glass window, Siena Cathedral

- Maestà – Tempera and gold on wood, Museum of Fine Arts Bern, Switzerland

- Madonna and Child – Tempera and gold on wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (formerly in the Stoclet Collection, Brussels, Belgium)[8][16]

- Madonna with Child and six Angels – Tempera and gold on wood, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, Perugia, Italy

- Polyptych: Madonna and Child with Saints Augustine, Paul, Peter, Dominic, four angels and Christ blessing (also known as Dossale no. 28; c. 1305) – Tempera and gold on wood, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

- Polyptych no. 47: Madonna and Child with Saints Agnes, John the Evangelist, John the Baptist, and Mary Magdalene; ten Patriarchs and Prophets, with Christ blessing – Tempera and gold on wood, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

- The Surrender of the Castle of Giuncarico – Fresco, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

- Maestà with Episodes from Christ's Passion – Tempera and gold on wood – Massa Marittima Cathedral, Italy

- Small Triptych: Flagellation of Christ; Crucifixion with Angels; Deposition in the Tomb – Tempera and gold on wood, Società di Esecutori di Pie Deposizioni, Siena

- Small Triptych: Madonna and Child with four Angels, Saints Dominic, Agnes and seven Prophets / Madonna con Bambino e con quattro angeli, i santi Domenico, Agnese, e sette profeti – Tempera and gold on wood – The National Gallery, London, England

- Portable Altarpiece: Crucifixion with Christ blessing; St Nicholas; St Gregory – Tempera and gold on wood, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, United States[17]

- Small Triptych: Crucifixion with Angels; Annunciation and Madonna with Child and Angels; Stigmata of St Francis with Madonna and Christ enthroned – Tempera and gold on wood, UK Royal Collection

- Maestá (Madonna with Child Enthroned and Twenty Angels and Nineteen Saints) – Tempera and gold on wood, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena

- Maestà (The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain) – Tempera and gold on wood – The Frick Collection, New York

- The Crucifixion (c.1315)– Tempera and gold on wood – New-York Historical Society, New York

References

[edit]- ^ "Duccio". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ Duccio. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 62. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- ^ Gordon, Dillian (28 July 2014). "Duccio (di Buoninsegna)". Oxford Art Online. Archived from the original on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ a b Smart 1978, p. 39.

- ^ White, John (1993). Art and Architecture in Italy 1250–1400. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055854.

- ^ smarthistory.khanacademy.org/duccio-madonna.html

- ^ a b "Madonna and Child Duccio di Buoninsegna (Italian, active by 1278–died 1318 Siena)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ Smart 1978, p. 40.

- ^ Polzer, Joseph (2005). "A Question of Method: Quantitative Aspects of Art Historical Analysis in the Classification of Early Trecento Italian Painting Based on Ornamental Practice". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorisches Institutes in Florenz. 49 (1/2): 33–100. JSTOR 27655375.

- ^ "Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 - The Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2024-11-28.

- ^ "Siena: The Rise of Painting | Exhibitions | National Gallery, London". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved 2024-11-28.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (October 30, 2024). "The Met's magical show of Sienese painting is the must-see of the season". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (October 17, 2024). "Art Show of the Season? It's These Centuries-Old Italian Paintings". The New York Times. pp. Section C, page 1. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ "Triptych: Crucifixion and other Scenes c. 1302–08". royalcollection.org.uk. 2018. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved Jul 27, 2018.

- ^ Christiansen, Keith. "Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 2004–2005." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 63 (Fall 2005), pp. 14–15, ill. on cover (color, cropped) and p. 14 (color).

- ^ "The Crucifixion; the Redeemer with Angels; Saint Nicholas; Saint Gregory, 1311–18, Duccio di Buoninsegna (Italian (Sienese), active in 1278, died by 1319)". Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Beck, James (2006). Duccio to Raphael. European Press Academic Publishing. ISBN 8883980433.

- Smart, Alastair (1978). The Dawn of Italian Painting 1250–1400. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 0714817694.

Further reading

[edit]- Bellosi, Luciano (1999). Duccio: The Maestà. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500237717.

- Bellosi, Luciano; Ragionieri, Giovanna (2003). Duccio di Buoninsegna. Giunti Editore. ISBN 978-8809032088.

- Deuchler, Florens (1984). Duccio. Milan: Electa. ISBN 8843509721.

- Jannella, Cecilia (1991). Duccio di Buoninsegna. Scala/Riverside. ISBN 978-1878351180.

- Cannon, Joanna; Campbell, Caroline; Wolohojian, Stephan (2024). Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350. ISBN 185709716.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Paintings by Duccio di Buoninsegna at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings by Duccio di Buoninsegna at Wikimedia Commons

- www.DuccioDiBuoninsegna.org 130 works by Duccio

- "The Missing Madonna: The story behind the Met's most expensive acquisition" The New Yorker Magazine, July 11 & 18, 2005, by Calvin Tomkins

- Duccio in Panopticon Virtual Art Gallery

- Duccio di Buoninsegna at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

- . . 1914.

- Carl Brandon Strehlke, "Archangel by the Workshop of Duccio di Buoninsegna (cat. 88)"[permanent dead link] in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works[permanent dead link], a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.