Romulo Espaldon

Romulo M. Espaldon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ambassador to Saudi Arabia and Yemen | |

| In office 1993–1999 | |

| President | Fidel Ramos |

| Preceded by | Abraham Rasul |

| Succeeded by | Rafael Seguis |

| Member of the Philippine House of Representatives from the Lone District of Tawi Tawi | |

| In office December 12, 1990 – June 30, 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Alawadin Bandon, Jr. (de facto) |

| Succeeded by | Nur G. Jaafar |

| Ambassador to Egypt, Somalia and Sudan | |

| In office 1984–1986 | |

| Preceded by | Jose V. Cruz |

| Succeeded by | Rafael E. Seguis |

| 1st Commissioner (later Minister) of Muslim Affairs | |

| In office 1979–1984 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Simeon Datumanong |

| 1st Regional Commissioner of Western Mindanao (Region IX) | |

| In office 1975–1979 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Bob Tugung (Lupong Tagapagpaganap ng Pook) |

| 1st Commander of the AFP Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) | |

| In office 1976–1980 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Delfin Castro |

| 1st Governor of Tawi-Tawi | |

| In office 1973–1974 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Nur G. Jaafar |

| AFP Deputy Chief of Staff | |

| In office 1971–1973 | |

| Preceded by | Eugenio Acab |

| Succeeded by | Rafael Ileto |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 16, 1925 Donsol, Sorsogon, Philippines |

| Died | August 27, 2005 (aged 79) Makati, Philippines |

| Alma mater | FEATI University United States Merchant Marine Academy US Naval War College National Defense College of the Philippines |

| Awards | US Congressional Gold Medal Légion d'honneur Bintang Yudha Dharma Presidential Merit Award Outstanding Achievement Medal Distinguished Service Stars Military Merit Medals Presidential Unit Citations Long Service Medal Philippine Liberation Medal Jolo Campaign Medal Anti-Dissidence Campaign Medal World War II Victory Medal American Campaign Medal Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Philippine Navy |

| Rank | |

| Unit | AFP Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) |

| Battles/wars | Moro conflict World War II |

Romulo Mercader Espaldon (September 16, 1925 – August 27, 2005) was a Filipino politician, military officer, civil servant and diplomat. He was the first naval officer to attain the rank of Rear Admiral in the Philippine Navy.[1] He became overall military commander in Mindanao at the height of the Muslim secessionist movement led by the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in the mid-1970s, during which he promoted a "Policy of Attraction"[2] which won the respect of many Muslims[3] and led 35,411[4] rebels to return to the fold of law by late 1978, and over 40,000[5] rebels by the early 1980s.

Early life and education

[edit]Espaldon was the son of Christian Bicolano teachers Cipriano Espaldon and Claudia Mercader. Heeding the call of the government to serve in the remotest places in the Philippines in the early part of the 20th century, his family moved from Sorsogon to Tawi-Tawi where his parents were pioneer educators.[6] His ability to speak Tausug and Sinama, and his understanding of Muslim custom[7] would later prove indispensable during his military and civilian career. He would eventually embrace Islam.[8]

He graduated as valedictorian from Bongao Elementary School in Tawi-Tawi in 1938, and with honors from Sulu High School in 1942.[9]

After World War II, Espaldon was sent to the Cooks and Bakers School of the Philippine Army at Camp Olivas where he graduated First Honor. On March 23, 1946, as he and his classmates were about to board a Douglas C-47 plane to return to Mindanao after graduation, he received orders that he would be retained as instructor at the school for having topped his class; hence, he remained at Camp Olivas.[9] That day, the plane that he was supposed to board crashed on Mount Banahaw, killing most of the military passengers on board.[10]

After instructing at Camp Olivas, he attended FEATI University as a scholar and pursued a degree in aeronautical engineering.[11]

In 1947, Espaldon was one of fifty Filipino scholars selected by nationwide competitive examinations for midshipman training at the United States Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA) at Kings Point, New York pursuant to the Philippine Rehabilitation Act of 1946.[12] Among his classmates were notable political activists Nemesio Prudente and Navy Capt. Danilo Vizmanos. An honor student and cadet officer, he eventually graduated valedictorian of the USMMA Deck Class of 1950 with an average of 90%. In 1995, he made history in the Academy as being only the third alumnus inducted into its Hall of Distinguished Graduates for being the first Academy graduate to attain the rank of Rear Admiral and for his successful efforts in bringing peace to Southern Philippines.[1]

In 1952, he took up the Anti-Submarine Warfare Deck Officers Course at the Naval Training College and finished first with a rating of 99%.[11]

In 1968, he graduated from the Naval Command Course at the US Naval War College.[13] A few years later, he obtained his master's degree in National Security Administration from the National Defense College of the Philippines where his academic performance was rated as "Superior." Out of thirteen foreign and local courses that he took, he topped six of them and the rest with honors.[11]

In 1981, the Western Mindanao State University (WMSU) conferred upon him a Doctor of Humanities honoris causa for his role in elevating Zamboanga State College into WMSU.

Military career

[edit]Espaldon's military career began at the age of 16 when he volunteered in the USAFFE as a member of the Bolo Battalion Unit in 1941 to fight the invading Japanese forces.[1] During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, he was a teenage guerrilla leader in Sulu and Tawi-Tawi.[14] He also served as intelligence officer of the 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment and as liaison officer between the Sulu Area Command and American landing forces (Sulu White Task Force) in Tawi-Tawi during the liberation campaign. He was later assigned as Garrison Commander of the Cagayan de Sulu Forces.[15] After World War II, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Philippine Army.

Shortly after graduating from Kings Point in 1950, he was commissioned as an ensign in the Philippine Navy and became commanding officer of RPS Capiz and later RPS Iloilo.[11] A decade later, he was appointed as naval attaché to Indonesia and Malaysia, and became fluent in Bahasa Indonesia.[16]

After returning to the Philippines, he served as Chief of Naval Intelligence in 1966, as Acting Chief of the Intelligence Service of the AFP (ISAFP) in 1969, then as Vice Commander of the Philippine Navy in 1971.[17]

In 1972, he would become Deputy Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), only to be deprived of the top post because the Marcos administration reportedly preferred a super-loyalist like General Fabian Ver. Veteran Associated Press correspondent Gil Santos noted that Espaldon was one of the few "good guys" who wanted to restore professionalism in the military and got sidelined by Marcos and Ver.[12]

That same year, the MNLF was founded by Nur Misuari as a splinter group of the Muslim Independence Movement. At its peak in 1974, it was able to field between 50,000 and 60,000 rebels,[18] and as many as 20,000 were reportedly trained in Sabah with financial assistance from Libya.[19]

From October 25, 1972, to August 31, 1973, Espaldon was designated as military supervisor of the Bureau of Customs due to the extortion syndicate and rampant smuggling that plagued the Bureau.[20][21] He would later be conferred the Outstanding Achievement Medal for his wide-ranging reforms which led to a 24% increase in revenue collection from the previous year, reduction in processing time from the usual ten (10) days to seventy-two (72) hours through the implementation of a computer-based Entry Control System, the elimination of the "cabo" system at the North Harbor, and the investigation and prosecution of thirty-seven cases involving customs irregularities.[22][23]

In 1973, Espaldon replaced his fellow Kings Point cadet Commodore Gil Fernandez as commanding officer of the AFP Southwest Command (SOWESCOM) reportedly to satisfy the terms of surrender of the MNLF Magic Eight rebel commanders. They had previously sought the relief of Fernandez who allegedly lacked sympathy for the Muslims.[24] This signaled a desire for a changed approach in Mindanao from that of hard-lining Fernandez.[7] With the assumption of Espaldon, his predecessor's Vietnam-style tactics of Body count and Search and destroy were abandoned in favor of his policy of attraction and peaceful reconciliation.

In addition to his military duties, he was appointed as the first governor of Tawi-Tawi[25] when it became a province on September 11, 1973, and served until the first provincial elections were held pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 302.[26] (Under the 1973 Constitution, only elective officials were prohibited from holding multiple government offices.) During the first 730 days of Tawi-Tawi as a province, Espaldon and Vice Governor Nur Jaafar spearheaded over 100 civilian infrastructure projects, including the construction of the provincial capitol, provincial hospital, public market, 50 mosques, school houses, radio station, airstrips, piers, houses, bridges, roads and water system.[27]

The following year, he was designated as the second military governor of the newly-created province of Basilan, but administered the affairs of government through Colonel Florencio E. Magsino.[28]

On December 29, 1973, Espaldon became the first naval officer to be donned the rank of rear admiral in the Philippine Navy.[6] That same day, Commodore Hilario Ruiz, then Flag Officer-in-Command of the Philippine Navy, was likewise promoted to rear admiral.[29]

On July 7, 1975, the Office of the Regional Commissioner for Region IX was created[30] within the policy of rapprochement, in reversal of the iron-fist approach[31] and Espaldon served as its first and only commissioner[32] until it was abolished and replaced with the Lupong Tagapagpaganap Ng Pook (LTP) in 1979.[33] He was succeeded by Ulbert Ulama "Bob" Tugung.

That same month, he led the signing and implementation of the Philippines-Indonesia Agreements on Border Crossing and Border Patrol[34] which enhanced the maritime security cooperation between the two countries, for which he would later be awarded the Bintang Yudha Dharma Pratama, Indonesia's second highest military order of merit.

In 1976, SOWESCOM would become the AFP Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) with Espaldon as its first commander.[16] As overall military commander in Mindanao, he was given full authority to command all forces in the south without the need to seek clearance from service chiefs to deploy troops.[2] The doubling of Espaldon's authority reportedly resulted from the fact that his tactics had reduced the war in the SOWESCOM area, while the achievements of the AFP Central Mindanao Command (CEMCOM) under Gen. Fortunato Abat had been less notable.[35]

That same year, he was appointed as member of the Agency for the Development and Welfare of Muslims in the Philippines which was chaired by Ambassador Lininding Pangandaman.[36]

Following the execution of the Tripoli Agreement in Libya on December 23, 1976, a ceasefire agreement was signed in Zamboanga City on January 20, 1977, between Espaldon and Dr. Tham Manjoorsa, authorized representative of the MNLF. A subsequent plebiscite led to the creation of two autonomous regions, Regions IX and XII, in Mindanao.[37]

By late 1978, Espaldon announced the collapse of the Northern Mindanao Revolutionary Command led by Abul Khayr Alonto and the surrender of 1,215 rebels, bringing the total to 35,411.[4]

Throughout his stint as overall military commander in Mindanao, Espaldon's "Policy of Attraction" saw over 40,000[5] rebels lay down their arms, although some non-government and non-MNLF skeptics feel that these figures may have been overstated.[38] Respected for both his competence and fairness, Espaldon had succeeded in persuading many MNLF personnel to accept amnesty and had reduced the level of fighting in the three Zamboanga provinces and in the Sulu archipelago.[39]

Many rebels also underwent officer training for integration into the AFP as part of its effort to restore peace in Mindanao.[40] Amilpasa "Caloy" Bandaying, who once belonged to the elite Top 90 of the MNLF before his surrender, was designated by Espaldon as his aide-de-camp despite being cautioned by his officers at SOUTHCOM.[41] Bandaying, in his article "The Bangsamoro Story (The Real Story Behind The Struggle),"[42] would later write:

Through a series of negotiation and dialogues, a number of MNLF armed combatants returned to the fold of the government and embraced the offer of peace and reconciliation as well as the promise of rehabilitation and resettlement – in line with the main promise of ending decades long of oppression and discrimination against Muslims and Lumads in Mindanao. Central to this campaign of reconciliation was Rear Admiral Romulo M. Espaldon, a native of Tawi-Tawi, tasked to dialogue with the MNLF in the thrust for finding a lasting peace in Mindanao.

Before his retirement on December 31, 1980, he was conferred the honorary title of Sultan Makasanyang (Sultan of Peace) by the Muslim communities of Autonomous Region IX. The Citation reads:

CITATION FOR RADM ESPALDON ON THE CONFERMENT OF THE HONORARY TITLE OF SULTAN MAKASANYANGBefore you assumed the reins of the Southern Command, the Muslims of Region IX were in the throes of constant fear, distrust and suspicion of the military and their Christian brothers. The military was looked upon by us as an enemy and the Christian Filipino as his ally.

Your assumption as Commander of SOUTHCOM transformed a situation of potential fratricidal war into one of cooperative brotherliness and of fruitful co-existence.

You have put away the fears from our communities and erased the distrust and suspicions from our minds.

This is your most important achievement as far as the Muslim communities of Autonomous Region IX are concerned.

You have accomplished even more.

You have raised the quality of our livelihood and way of living. You have helped us elevate our places of prayer from Nipa structures to concrete and beautiful edifices; set up cultural centers where Islam may be taught as a religion and a culture that are contributive to Philippine civilization.

You have given us public markets where we may sell our catch from the sea and the produce from our farms; given us roads whereon to carry these from dungkaan and farm to the final consumer. You have constructed rock causeways for us to dock with safety and waterworks where with to secure safe and abundant potable water.

From objects of traditional government neglect you have elevated us, the Muslims of Autonomous Region IX, into first class citizens attended to by the government and its various instrumentalities on equal footing with our Christian brothers.

Now therefore we, representing the Muslim communities of Autonomous Region IX, confer upon you Rear Admiral Romulo M. Espaldon, the Honorary Title of SULTAN MAKASANYANG.

GIVEN this 22nd day of SAFFAR 1401 (28th day of December 1980), Zamboanga City, Philippines.

Civilian career

[edit]In 1979, Espaldon was appointed as the first commissioner of the Commission on Islamic Affairs,[43] which became the Ministry of Muslim Affairs in 1981.[44] Under his leadership, the Philippine Shari'ah Institute was launched and spearheaded the translation of the Code of Muslim Personal Laws from English to Arabic,[45] and the first Madrasa policy conference was held to discuss the integration of Madrasa-type education into the Philippine Educational System.[46] He was also chairman of the Philippine Pilgrimage Authority and served as Amirul Hajj in 1981 and 1984.

He likewise became active in civic organizations such as the Boy Scouts of the Philippines where he served as Vice-President from 1981 to 1984, and Lions Clubs International where he served as District Governor from 1983 to 1984.

In 1990, he served as representative of the lone Legislative district of Tawi-Tawi during the 8th Congress of the Philippines after winning his election protest against Alawadin T. Bandon, Jr., making him the first elected representative of Tawi-Tawi.[47] Among the bills that he filed were House Bill No. 35166 (An Act Creating the Sulu Archipelago Development Authority) and House Bill No. 35187 (An Act Requiring Conspicuous Identification Markings on Water Vessels).[48]

In the diplomatic service, Espaldon was appointed as Philippine Ambassador to Egypt, Sudan and Somalia from 1984 to 1986,[49] and to Saudi Arabia and Yemen from 1993 to 1998.[50] He was also appointed Honorary Ambassador-at-large to Guam in 1990. During his stint as envoy to Saudi Arabia, he often reminded embassy personnel that one of their primary objectives was to serve and protect Overseas Filipino Workers.[6]

His legacy and effectiveness as a peace negotiator was once again acknowledged when jihadist militant group Abu Sayyaf declared during the 2000 Sipadan Hostage Crisis that they would release three female hostages if the government agrees to have a new set of negotiators composed of Espaldon, Sen. Ramon Magsaysay Jr., and Sultan Rodinood Kiram.[51] However, the request was turned down by the government.[52] In 2003, he was advisor of a government panel that met with Prof. Shariff Julabbi, founder of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front splinter group Bangsamoro Mujahideen Alliance.[53]

Notable career events

[edit]Creation of Tawi-Tawi Province

[edit]Espaldon lamented the fact that government services would mostly reach Jolo but barely reach Tawi-Tawi when it was still part of the Province of Sulu, which worsened poverty and insurgency in the area. According to Espaldon, President Marcos asked him, "Why are the young boys of Tawi-Tawi easily wooed by the Moro National Liberation Front?" Espaldon replied, "The Sama boys, like their elders and leaders, are tired and weary of their union with the Province of Sulu. They want to have their own leaders and manage their own affairs. If His Excellency wants to solve the problem, I recommend that he create them into a separate province and allow them to exercise their own local prerogatives."[54] Soon after, Presidential Decree No. 302 was signed creating the province of Tawi-Tawi.[26] Hence, Espaldon earned the moniker "Father of Tawi-Tawi."

Surrender of the MNLF Magic Eight

[edit]In October 1973, then Commodore Espaldon received information that the so-called Magic Eight rebel commanders of the MNLF, composed of Abbas "Maas Bawang" Estino, Gerry Matba, Bagis Hassan, Ahmad Omar, Jairulla Abdurajak, Alih Abubakar and Tupay Loong, wanted to surrender to him, along with their 2,000 fighters. It was agreed that the rebels would be brought down from the hills to the shore of Panamao beach in Jolo, while Espaldon would anchor his ship about 500 yards from the shore and wait for the eight commanders to board the ship where the surrender ceremonies would take place. By noon time, none of the eight commanders had arrived at the ship. It was already afternoon when Kumander Maas Bawang arrived in a small pump boat. He requested to speak with Espaldon, and in the Tausug dialect, relayed the rebels' request for Espaldon to come ashore and personally accept their surrender. Despite the last-minute change in plan, Espaldon agreed. With a small pump boat and eight of his men, all unarmed, Espaldon arrived at the beach. The rebels rushed to Espaldon and his men and started embracing them, crying, and saying that the government is sincere.[55]

Hijacking of MV Don Carlos

[edit]On April 30, 1978, MV Don Carlos of Sulpicio Lines was hijacked and its 56 hostages held captive by terrorists who demanded 700,000 pesos (nearly 20 million pesos in 2020) for their release. Later, the ransom demand was dropped in exchange for the release of some rebel prisoners, but the military also rejected this. "We are ready to assist the Basilan terrorists provided they release the hostages without ransom," Espaldon said. After 23 days of fighting with their captors on Basilan island, government forces finally obtained the release of all hostages.

According to Sulpicio Lines vice-president BGen Emilio Alcoseba (ret.), the company did not pay a single centavo of ransom for the release of the 56 crew and passengers. "Without the assistance of Admiral Espaldon and General Luga, the terrorists would not have been pressured into releasing the hostages," he said.[56]

Hijacking of Suehiro Maru

[edit]On September 26, 1975, Japanese freighter Suehiro Maru was hijacked in Zamboanga and its 29 crew members held hostage by some 40 terrorists who demanded $133,000 (nearly $700,000 in 2020) for their release. After considerable pressure from Espaldon who formed a blockade with a fleet of 11 Navy ships, the rebels progressively softened their demands and eventually offered to release the ship and the crew in return for safe passage without a single cent being paid as ransom.[57]

Kidnapping of Eunice Diment

[edit]On February 28, 1976, British missionary-translator Eunice Diment, who was working among the Sama Banguingui, was kidnapped from a boat off Basilan Island by official action of the Basilan Revolutionary Committee of the MNLF's regional command in Basilan.[39][58] She was released unharmed on March 17 with no ransom being paid.[59] The Hong Kong-based Far Eastern Economic Review noted that reactions to her kidnapping were "a good example of how Espaldon and his officers work."[60]

Kidnapping of Pierre Huguet

[edit]On February 26, 1978, Pierre Huguet, a senior official in the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs, was abducted while holidaying in Zamboanga City.[61] Huguet was taking photos of houses on stilts in Zamboanga Bay when he was pushed into the water by three rebels, pulled into a boat, and was held captive for $132,000 in ransom (over $500,000 in 2020) on Basilan island. A note saying "Please send the money immediately," believed to have been dictated to Huguet by the kidnappers, was transmitted to his wife in Manila. Espaldon coordinated with French Ambassador Raphaël-Léonard Touze regarding courses of action and eventually secured the peaceful release of Huguet without paying ransom, pursuant to government policy.[62][63] However, the government reportedly paid for the "expenses" incurred by the guerrillas in keeping Huguet for two weeks as a concession.[64] Espaldon would later be conferred the Légion d'honneur, the highest French order of merit.

Battle of Jolo

[edit]On February 7, 1974, government forces began a military offensive against MNLF forces that managed to take control of the municipality of Jolo, Sulu, resulting in a large number of civilian and military casualties and substantial damage to the municipality. Considering Espaldon's preferred "Policy of Attraction" which saw a period of rebel returnees reintegrating into the mainstream, he reportedly opposed military operation in Jolo but was apparently overruled by the central government.[65][66][67] He would later be remembered for sending naval ships to the Jolo Pier and being the "prime mover" of stranded Joloanos to safety.[68][69][70]

In the aftermath, he was made part of the Executive Committee of the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Rehabilitation of Jolo.[71]

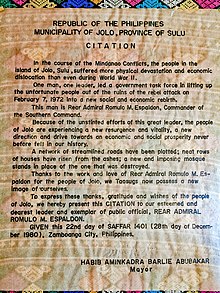

Six years after the Battle of Jolo, the Municipality of Jolo presented a Citation to Espaldon which reads:

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINESMUNICIPALITY OF JOLO, PROVINCE OF SULUCITATIONIn the course of the Mindanao Conflicts, the people in the Island of Jolo, Sulu, suffered more physical devastation and economic dislocation than even during World War II.

One man, one leader, led a government task force in lifting up the unfortunate people out of the ruins of the rebel attack on February 7, 1972 (sic) into a new social and economic rebirth.

This man is Rear Admiral Romulo M. Espaldon, Commander of the Southern Command.

Because of the unstinted efforts of this great leader, the people of Jolo are experiencing a new resurgence and vitality, a new direction and drive towards an economic and social prosperity never before felt in our history.

A network of streamlined roads have been plotted; neat rows of houses have risen from the ashes; a new and imposing mosque stands in place of the one that was destroyed.

Thanks to the work and love of Rear Admiral Romulo M. Espaldon for the people of Jolo, we Taosugs now possess a new image of ourselves.

To express these thanks, gratitude and wishes of the people of Jolo, we hereby present this CITATION to our esteemed and dearest leader and exemplar of public of official, REAR ADMIRAL ROMULO M. ESPALDON.

GIVEN this 22nd day of SAFFAR 1401 (28th day of December 1980), Zamboanga City, Philippines.

HABIB AMINKADRA BARLIE ABUBAKARMayor

In the media

[edit]

Espaldon appeared twice on the cover of Asiaweek.[72][73]

He also appeared in the March 1977 issue of National Geographic.[74] In his article, Don Moser wrote:

Admiral Espaldon took the floor to hear grievances. An old man, a refugee from the fighting, said he wished to return to his home. Espaldon pointed to the local military commander and said, "Colonel, you will arrange for him to go to his original abode." Another man complained that federal funds due his community had not yet arrived, and Espaldon called the local commissioner in charge to the platform. When the man made excuses about the funds not yet arriving through channels, Espaldon strode to the microphone and thundered, "You, commissioner, will go to Manila yourself and get the funds!" The audience applauded. It was an impressive display of on-the-spot problem solving.

Later, riding back to Zamboanga on a patrol boat, I asked the admiral about it. "The rebels who are still in the mountains are watching to see what we do," he said. "The President has appointed Muslim judges, mayors, governors. The government is building irrigation systems, roads, schools. In this area, within a year's time, there will be no major fighting."

In January 1984, he was featured on the cover of Mr. & Ms., a weekly opposition tabloid magazine created in response to the Assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr., and named as one of the 50 Most Capable To Lead.[75]

Notable awards

[edit]

Philippine Awards

[edit] Presidential Merit Award

Presidential Merit AwardOutstanding Achievement Medals[29]

Distinguished Service Stars[17]

Distinguished Service Stars[17] Military Merit Medals[17]

Military Merit Medals[17] Presidential Unit Citations[17]

Presidential Unit Citations[17] Long Service Medals

Long Service Medals Philippine Liberation Medal[17]

Philippine Liberation Medal[17] Jolo Campaign Medal[17]

Jolo Campaign Medal[17]- Anti-Dissidence Campaign Medal[11]

- Doctor of Humanities honoris causa, Western Mindanao State University (1980)[76]

- Distinguished Achievement Award, National Defense College of the Philippines (1988)

- Aurora Aragon Quezon Award (1979)

- Gintong Ama Award for Government and Public Service (1988)

Foreign Awards

[edit]- US Congressional Gold Medal for Filipino Veterans of World War II (posthumous; 2022)[77]

Légion d'honneur (1978)[1]

Légion d'honneur (1978)[1] Bintang Yudha Dharma Pratama (1978)[1]

Bintang Yudha Dharma Pratama (1978)[1] World War II Victory Medals[17]

World War II Victory Medals[17] Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medals[17]

Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medals[17] American Campaign Medal[17]

American Campaign Medal[17]- USMMA Hall of Distinguished Graduates (1995)[1]

- USMMA Distinguished Service Award[78]

Personal life

[edit]Espaldon was married to Eleanor Asistores whom he met on Polillo Island while his ship was assigned to patrol the eastern coast of Luzon. They raised seven children.

Death

[edit]

Espaldon died due to colon cancer in 2005 at the age of 79 and was given full military honors during his interment at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.[6]

Memorial

[edit]

In 2009, the Philippine Navy issued HPN General Order No. 229 renaming Naval Station Zamboanga, the headquarters of Naval Forces Western Mindanao, as Naval Station Romulo Espaldon in his honor.[79]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Romulo M. Espaldon '50". www.usmmaalumni.com. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pacific Stars And Stripes Newspaper Archives". newspaperarchive.com. May 4, 1976. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Noble, Lela (1977). "Philippines 1976: The Contrast between Shrine and Shanty". Asian Survey. 17 (2): 138. doi:10.2307/2643471. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2643471.

- ^ a b McCoy, Alfred W. (2009). An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-299-22984-9.

- ^ a b Hollie, Pamela G. (March 10, 1982). "Marcos to Visit Saudi Arabia to Ease Moslem-Rebel Issue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Former Philippine Envoy to Riyadh Dies at 79". Arab News. September 5, 2005. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ a b US Department of State (1973). State Dept. Cable 1973-14971: Espaldon Replaces Fernandez at SOWESCOM. Declassified June 30, 2005.

- ^ Rosaldo, Renato (October 9, 2003). Cultural Citizenship in Island Southeast Asia: Nation and Belonging in the Hinterlands. University of California Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-520-22748-4.

- ^ a b Arpon, Winston (1979). Laughter in the South: Footnotes to the Southern Philippines Conflict. Bustamante Press, Inc. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas C-47B-1-DL (DC-3) 43-16211 Banahao Mountain". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Silvero, Aquilino (1976). History of the Philippine Navy. Philippine Navy Headquarters. pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Navarro, Nelson A. (October 31, 2017). Doc Prudente: Nationalist Educator. Anvil Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-971-27-2921-8.

- ^ "U.S. Coast Guard 1790-1968". Naval War College Review. 21 (1): 43–53. 1968. ISSN 0028-1484. JSTOR 44639349.

- ^ Espaldon, Ernesto M. (1997). With the Bravest: The Untold Story of the Sulu Freedom Fighters of World War II. Espaldon-Virata Foundation. ISBN 978-971-91833-1-0.

- ^ Velasquez, M.A. History of the Sulu Area Command. p. 170.

- ^ a b Soliven, Max V. "GMA calls for 'unity,' but what is she doing to Zamboanga City?". philstar.com. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i General and Flag Officers of the Philippines. Association of General and Flag Officers. p. 99.

- ^ Steinberg, David Joel (1982). The Philippines, A Singular and A Plural Place. Internet Archive. USA: Westview Press, Inc. p. 107. ISBN 0-89158-990-2.

- ^ Villadolid, Alice (August 15, 1975). "Philippines Reports Truce in Mindanao". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "October 25, 1972". The Philippine Diary Project. October 25, 1972. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Official Week in Review: June 15 – June 21, 1973 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Glimpses of Micronesia & the Western Pacific. Glimpses of Guam Incorporated. 1980. p. 50.

- ^ AFP General Orders No. 89 dated August 31, 1973

- ^ Castro, Delfin (2005). A Mindanao Story: Troubled Decades in the Eye of the Storm. p. 11.

- ^ "Letter of Instruction No. 116, s. 1973, Designation of Romulo Espaldon as Governor of Tawi-Tawi". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Presidential Decree No. 302, s. 1973, Creating the Province of Tawi-Tawi". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ Tawi Tawi After 730 Days: A Report To The People. September 11, 1975.

- ^ "Lamitan City Official Website | Historical Background". lamitancity.gov.ph. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Empredad, Antonio (1979). The Philippine Navy in the New Society. Philippine Navy Office of Naval History.

- ^ "Presidential Decree No. 742, s. 1975 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Muslim Leaders of the Philippines. Foreign Service Institute, Department of Foreign Affairs. 1989. p. 21.

- ^ "ARMM History". Civil Service Commission. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Presidential Decree No. 1639, s. 1979 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Indonesian News and Views. Embassy of Indonesia, Information Division. 1974. p. 191.

- ^ Espaldon Supremo in the South. Hong Kong: Far Eastern Economic Review. April 1976. p. 14.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 474, s. 1976 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Proclamation No. 2045, s. 1981 | Proclaiming the Termination of the State of Martial Law Throughout the Philippines". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Roces, Marian Pastor. "September 21, 1972 to January 31, 1981 (Martial Law)". Muslim Mindanao Museum. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Noble, Lela Garner (1976). "The Moro National Liberation Front in the Philippines". Pacific Affairs. 49 (3): 405–424. doi:10.2307/2755496. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2755496.

- ^ Pathé, British. "Philippines: Moslem Rebels Became Philippine Army Officers". www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Marohomsalic, Nasser A. (2001). Aristocrats of the Malay Race: A Historic of the Bangsa Moro in the Philippines. N.A. Marohomsalic.

- ^ Bandaying, Amilpasa. "The Bangsamoro Story | Politics Of Asia | Philippines". Scribd. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Official Week in Review: July 23 – July 29, 1979 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 697, s. 1981 | Creating the Ministry of Muslim Affairs". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ Abdulkarim, Prof. Kamarodin A. "IS 110 - Introduction to Islamic Law and Jurisprudence". Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Address of President Marcos on the First Anniversary of the Ministry of Muslim Affairs | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "House of Representatives | Roster of Philippine Legislators". www.congress.gov.ph. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Senate Legislative Digital Resource".

- ^ "Embassy of the Philippines in Cairo, Egypt | The Embassy".

- ^ "Embassy of the Philippines in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Historical Background".

- ^ Summary of World Broadcasts: Asia, Pacific. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. p. 7.

- ^ "Sipadan Hostage News Specials". December 13, 2004. Archived from the original on December 13, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Letter to the President". www.smjsite.info. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Tahang, Nash (March 2005). "Espaldon: The Unifying Leader". Tawi-Tawi Mirror Magazine. 1 (2): 9–10.

- ^ "Rear Admiral Romulo Espaldon". YouTube. 1980.

- ^ Arillo, Cecillo (May 25, 1978). "Terrorists free 56 hostages". Times Journal.

- ^ "Philippine Navy Forces Rebels To Yield Ship and 29 Hostages". The New York Times. September 30, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Diment, Eunice (1976). Kidnapped!: Eunice Diment's Story. Paternoster Press. ISBN 978-0-85364-199-5.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2002). The Encyclopedia of Kidnappings. Infobase Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4381-2988-4.

- ^ Far Eastern Economic Review. April 1976. p. 11.

- ^ "Un haut fonctionnaire français M. Pierre Huguet, a été enlevé par des musulmans". Le Monde.fr (in French). February 28, 1978. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Age from Melbourne, Victoria, Australia on March 4, 1978 · Page 6". Newspapers.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Philippines: Kidnapped French Official Pierre Huguet Reunited with Family, retrieved May 14, 2020

- ^ "The Vancouver Sun from Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada on March 13, 1978 · 13". Newspapers.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Saada, Noor (February 8, 2017). "KISSA AND DAWAT: The 1974 Battle of Jolo, narratives and quest for social conscience". MindaNews. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Saada, Noor (February 11, 2017). "KISSA AND DAWAT: 1974 Battle of Jolo, narratives and quest for social conscience". Mindanao Daily. pp. 4–5. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ US Department of State (February 13, 1974). State Dept cable 1974-15327: Jolo City Destroyed in Muslim Rebel Attack. Declassified June 30, 2005.

- ^ Aliman, Agnes Shari Tan (2021). The Siege of Jolo, 1974. Central Books. ISBN 978-621-02-1271-6.

- ^ Sadain Jr., Said (February 8, 2016). "THAT WE MAY REMEMBER: February 7, 1974: The Jolo-caust". MindaNews. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Tan, Michael L. (May 26, 2017). "From Jolo to Marawi". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ "Memorandum Order No. 426, s. 1974 | Structuring the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Rehabilitation of Jolo". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Philippine South: PEACE". Asiaweek. February 11, 1977.

- ^ "Sabah: The Problem That Won't Go Away". Asiaweek. December 28, 1979.

- ^ National Geographic. National Geographic Society. 1977. pp. 389–391.

- ^ "A Question of Leaders: 50 Most Capable To Lead As Named in Mr. & Ms. Survey". Mr. & Ms. Special Edition. January 6, 1984.

- ^ "Instituto Cervantes' Spanish director receives honorary degree from Zamboanga university". bayanihan.org. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Publisher, C. M. S. "AWARDING OF U.S. CGM TO FILIPINO WWII VETERANS RESUMES AFTER TWO YEARS - PVAO". Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "Distinguished Service Award". www.usmmaalumni.com. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Farolan, Ramon (December 7, 2009). "Philippine Daily Inquirer | Of Naval Heroes". Retrieved May 9, 2020 – via PressReader.