Paris Psalter

The Paris Psalter (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. gr. 139) is a Byzantine illuminated manuscript, 38 x 26.5 cm in size, containing 449 folios and 14 full-page miniatures. The Paris Psalter is considered a key monument of the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, a 10th-century renewal of interest in classical art closely identified with the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (909–959) and his immediate successors.

In the classification of Greek biblical manuscripts, it is designated by siglum 1133 (Rahlfs).

Description

[edit]The Paris Psalter is a copy of the 150 Psalms of David, translated from Hebrew into demotic Greek. The psalter is followed by the Canticles of the Old Testament, a further series of prayers. Both these texts were particularly well-suited for use by members of the laity in private devotional exercises. The popularity of this use of the psalter is reflected in the numerous extant luxury copies, often lavishly illuminated, made for royal and aristocratic patrons.[1] The Paris Psalter is the pre-eminent Byzantine example of this genre.

The Paris Psalter includes not only the biblical texts, but an extensive interpretive gloss of the entire cycle of prayers. This commentary, which comprises quotations and paraphrases of patristic exegetical works, surrounds the verses. Even though it is written in a smaller pitch than the primary text, the gloss occupies far more of each page than the psalms, which are reduced to a few verses per page. The length of the gloss causes the longer psalms to occupy up to 8 pages.

Glossed biblical texts were usually commissioned by monastic libraries, clerics and theologians. The classical and royal iconography and sumptuousness of the Paris Psalter, however, strongly point to an imperial patron; while the gloss implies a reader with serious intellectual and spiritual inclinations, such as Constantine VII.

The manuscript is written in a minusucule bouletée hand, which closely resembles that of several other Byzantine manuscripts of the same period, including an illuminated gospel book, (Parisinus graecus 70); a Gospel Book (London, British Library Add MS 11 300); a Gospel Book (Venice, Biblioteca Marciana Marcianus graecus I 18); the Acts and Epistles (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Gr. 110); and Basil of Caesarea (Oxford, Corpus Christi 26). These books, along with the Paris Psalter, were, in all likelihood, produced in the same Constantinopolitan scriptorium.

The manuscript’s importance in art history is based on the 14 superb, full-page illuminations that illustrate its texts. These singleton pages were tipped in to the manuscript and are not part of its regular gathering structure. The first seven images preceding the text depict scenes from the life of David, the author of the psalms, who is usually accompanied by personifications. The eighth miniature marks the beginning of the penitential Psalms; and the last 6, depicting Moses, Jonah, Hannah, Ezekiel and Hezekiah, introduce and illustrate the Canticles of the Old Testament. The subject of the miniatures is as follows:

1v: David playing the harp with Melodia (μελωδία) seated beside him;

2v: David kills the lion assisted by Strength (ἰσχύς);

3v: The anointing of David by Samuel, with Lenity (πραότης) observing;

4v: David, accompanied by Power (δύναμις) slays Goliath, as Arrogance (ἀλαζόνεια) flees;

5v: Triumphant Return of David to Jerusalem;

6v: Coronation of David by Saul;

7v: David Stands with a psalter open to Psalm 71, flanked by Wisdom (σοφία) and Prophecy (προφητεία);

136v: Nathan Rebukes David concerning Bathsheba; the Penitence of David with Repentance (μετάνοια);

419v: Moses parting the Red Sea, with personifications of the desert, night, the abyss, and the Red Sea;

422v: Moses Receives the Tablets of the Law;

428v: Hannah thanks God for the birth of Samuel;

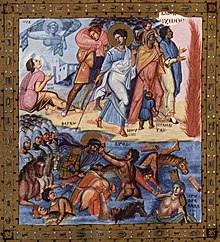

431v: Scenes from Jonah;

435v: Isaiah with Night (νύξ) and Dawn (ὄρθρος);

446v: King Hezekiah.

Jean Porcher has assigned the full-page illuminations to five artists, or hands, attributing 6 miniatures to the lead artist, Hand A.[2]

History

[edit]The full-blown classicism of the painting style and iconographic parallels with Roman wall painting led 19th-century scholars to date the manuscript to the early 6th century. In the early 20th century, however, Hugo Buchthal and Kurt Weitzmann, took issue with the Late Antique dating, conclusively demonstrating that the fully realized, confident classicism and illusionism of the miniatures were the product of the 10th century, thereby extending the persistence of classical art in Byzantium well into the Middle Ages.

The majority of the full-page illuminations depict key scenes from the life of King David. The iconography of the miniatures alludes to David's authorship of the psalms, but scenes like Samuel anointing David and the Coronation of David by Saul emphasize the former's status as a divinely-appointed ruler. The emphasis on biblical kingship and the studied classicism of the miniatures has led scholars to propose the scholar emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905–959) as the patron and/or owner of the manuscript, which would locate its production in the imperial scriptorium. Known not only for his interest in classical texts, but for his artistic abilities as well, Constantine VII may have directly supervised the team of artists.[3] Whether the psalter was intended for Constantine VII’s personal use, or ordered as a gift for his son, Romanos II at the time of his elevation to the status of co-emperor in 945, its text and images of David would have been interpreted as biblical examples of kingship on which the Christian emperor might model his own rule and moral conduct.

Although the astonishing classicism and emphasis on kingship strongly suggest the imperial patronage of Constantine VII, the earliest documentation of the manuscript takes the form of copies of several of the miniatures that appear in several 13th-century manuscripts.[4] These copies suggest that the manuscript was in the imperial library after the expulsion of the Latin usurpers, and continued to be highly regarded in the Paleologan period.

The provenance proper begins in 1558, when Jean Hurault de Boistaillé, the French ambassador to Constantinople, acquired the book from the Sultan Suleiman I. The acquisition of the book and its price are recorded in an inscription on fol. 1r: Ex bibliotheca Jo. Huralti Boistallerii. Habui ex Constantinopoli pretio coronatorum 100. The library of the Hurault family was acquired for the Bibliothèque du Roi in 1622, which became the core collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Illustrations

[edit](Excluding those illustrated above)

- Paris Psalter, full-page illuminations

-

Paris Psalter, Hannah’s Prayer, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 428v.

-

Paris Psalter, Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 422v.

-

Paris Psalter, David Glorified by the Women of Israel, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 5v.

-

Paris Psalter, Isaiah’s Prayer, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 435v.

-

Paris Psalter, David Holding Open Psalter with Wisdom and Prophecy, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 7v.

-

Paris Psalter, David fighting the lion with Strength, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 2v.

-

Paris Psalter, Scenes from Jonah, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 431v.

-

Paris Psalter, David Crowned by Saul, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 6v.

-

Paris Psalter, David anointed by Samuel, c. 950, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ms. grec 139, fol. 3v.

David Composing the Psalms miniature, fol. 1v

[edit]David Composing the Psalms (or David the Harpist) miniature depicts David sitting beside a personification of Melody as he composes the Psalms. To the right of David, the nymph Echo watches him play his harp from behind a stele. In the bottom right corner of the painting a semi-nude personification of Mount Bethlehem reclines while wearing a wreath of laurels. David is surrounded by sheep, goats, and a shepherding dog, referencing the myth of Orpheus, who was able to charm animals with his music.[5]

The scene is located in a natural, classical, landscape. There are multiple types of vegetation present in the miniature, including trees, various bushes, and tall reeds. The illustration also has various natural features such as mountains, ravines, and a stream. This setting is potentially alluding to an older Roman mosaic from Tarsus in Cilicia that depicts Orpheus charming animals in a mountainous setting.[6] However, David has the addition of a depiction of the city of Bethlehem in the upper left corner, which contrasts with the rest of the naturalistic setting. The coupling of Melody and David within the painting is also highly reminiscent of classical art. The two figures continue an established trend of depicting linked and loving couples but repurposes the imagery to depict a Christian story.[7]

The David the Harpist miniature functions as an artwork with a dual political and religious meaning. The illustration conveys a religious story, in which David is depicted as a Christ-like figure. Additionally, a more secular interpretation is that within the artwork David is depicted as a model for an ideal king or political leader.[5] This is further enhanced by the imagery in the piece that alludes to the myth of Orpheus, who used his skills to pacify his enemies, much like how he tamed beasts.

David and Goliath miniature, fol. 4v

[edit]

The David and Goliath miniature, fol. 4v, depicts the final battle between the young David and Goliath, with David defeating Goliath.[8] The painting also represents an encomium, or the praise of a person or thing, in relation to the rulers of Macedonia.[9] The spiritual context, however, builds on the concept of imperial organization being sanctioned by God. The painting can also be viewed as an allusion to Christ's triumph over Satan (spiritual) or the victory of a ruler over an adversary (secular).[10] The Paris Psalter is very famous within ancient Byzantine art, and although there are other psalters, this is the most famous out of the seventy five illuminated Byzantine psalters. A common theme in the Paris Psalter is the portrayal of ideal rulers, this portrayal is meant to signify their importance in their era and to glorify them.[9]

The story of David and Goliath begins in the valley of Elah, where the Philistine army and Saul's army met in battle. Goliath was a Philistine giant who repeated appeared on a hill to challenge the Saul army, a challenge to which none of Saul's army accepted. David's three older brothers were members of Saul's army, while due to David's young age he stayed at home. Whilst delivering supplies to his brothers on the battlefield, David's pride made him determined to defeat this giant for the sake of his people. With the permission of King Saul, David set out on his mission to defeat Goliath, and the conflicts between them began.[11] Although the identity of the artist of the Paris Psalter and David and Goliath within it remains unknown, this history of conflict between David and Goliath was the inspiration for the depiction of David's victory over Goliath.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Kurt Weitzmann, “The Ode Pictures of the Aristocratic Psalter Recension,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 30 (1976): 67–84, here p. 73; and idem, “The Psalter Vatopedi 761: Its Place in the Aristocratic Psalter Recension,” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 10 (1947): 21–51, here p. 47.

- ^ Porcher, Jean (1958). Byzance et la France Médiévale: Manuscrits à Peintures du 11e au XVIe Siècle. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale. ISBN 9782717700374.

- ^ Beckwith, John (1970). Early Christian and Byzantine Art. Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth: Penguin. pp. 201–207.

- ^ See, for example, the miniature of David and Nathan in the late 13th-century psalter now in the Greek Patriarchate Library in Jerusalem.

- ^ a b Stokstad, Marilyn (2004). Medieval Art (2nd ed.). Colorado: Westview Press. pp. 130–131.

- ^ Maguire, Henry (1989). "Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial Art". Gesta. 28 (2): 218.

- ^ Buchthal, Hugo (1938). The Miniatures of the Paris Psalter: A Study In Middle Byzantine Painting. Studies of the Warburg Institute. Vol. 2. London: Warburg Institute. p. 14.

- ^ Wander, Steven H. (1973). "The Cyprus Plates: The Story of David and Goliath". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 8: 89–104. doi:10.2307/1512675. JSTOR 1512675.

- ^ a b "The Byzantine Legacy".

- ^ "The Paris Psalter".

- ^ "David and Goliath". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

References

[edit]- Wander, S. (2014). The Paris Psalter (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, cod. gr. 139) and the Antiquitates Judaicae of Flavius Josephus. Word & Image, 30(2), 90–103.

- Anderson, J. (1998). Further Prolegomena to a Study of the Pantokrator Psalter: An Unpublished Miniature, Some Restored Losses, and Observations on the Relationship with the Chludov Psalter and Paris Fragment. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 52, 305–321.

- H. Buchthal. (1938). The Miniatures of the Paris Psalter : A Study in Middle Byzantine Painting, Studies of the Warburg Institute, Vol. 2 (London: Warburg Institute, 1968).

- Maxwell, Kathleen. (1987). “The Aristocratic Psalters in Byzantium,” Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, 62, 406.

- Lowden, J. (1988). “Observations on Illustrated Byzantine Psalters.” The Art Bulletin, 70(2), 242–260.

External links

[edit]- Paris Psalter (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS. gr. 139) – Complete high resolution scan of the manuscript on Gallica.