Ancient theater of Alauna

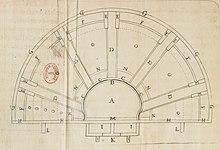

Hypothèse de restitution (2020). Attested or restored structures Hypothetical structures threshold | |

| Location | Manche, Valognes, France |

|---|---|

| Region | Normandy |

| Coordinates | 49°30′20″N 1°26′47″W / 49.50556°N 1.44639°W |

| Altitude | 57 m (187 ft) |

| Type | Roman theatre |

The ancient theater of Alauna is a Roman-era spectacle building located in the French commune of Valognes, in the department of Manche.

The monument is a member of a group of theatres with an arena whose plan diverges from that of classical Roman theatres, thereby enabling the presentation of diverse performances. The structure was constructed using small limestone rubble from the local area, with a diameter exceeding 72 meters. The semicircular cavea and elliptical orchestra are served by five radiating vomitoria and two corridors along the stage wall. The decumanus maximus of the ancient settlement of Alauna passes at the top of the cavea, necessitating a change in its course.

Situated at the eastern periphery of the settlement, the structure was likely erected during the latter half of the first century and subsequently abandoned by the end of the third century. Following this, the masonry was dismantled and repurposed until the modern era. The site's remains are buried at a shallow depth beneath enclosed meadows, with a portion of its enclosing wall visible within one of these hedges. The site has been the subject of multiple studies, including investigations conducted in 1695, and the mid-1840s, and as part of a comprehensive investigation program on the Alauna site in 2015 and 2020.

Geography and archaeological context

[edit]The theater in the contemporary landscape

[edit]

Alauna is 1.6 km southeast of the modern town of Alleaume (commune of Valognes, Manche department) on the northwest edge of a plateau between two parallel talwegs oriented northwest-southeast that border it to the east and west.[1] The theater is situated at the place designated as "Les Buttes," situated to the southeast of the Castelet manor. Its cavea faces north-northeast. It is on the southern slope of the easternmost talweg within a bocage landscape, characterized by enclosed pastures with hedges.[B 1]

The plateau overlooks the southeastern aspect of the Merderet River valley, situated near its source. This valley was formed during the Hettangian period (Lower Jurassic) as a consequence of marine transgression. The local geological resources, including red clays, sands, and cobbles or pebbles from the Rhaetian (Upper Triassic) of the plateau and Triassic limestone on the slopes, were utilized in the construction of the buildings at Alauna, including the spectacle building.[2][3] While a significant portion of the Alauna site is situated at an elevation of over 50 meters, reaching as high as 60 meters in proximity to the spectacle building, another section of the site follows the topography of the valley slope towards the Merderet, with gradients occasionally reaching 10%.[4] The town of Valognes, including Alleaume, is located on the opposite bank of the river.[A 1]

The theater within Alauna

[edit]

The theater is situated at the eastern periphery of the ancient settlement of Alauna, which is estimated to encompass an area of approximately 45 hectares. Alauna is located southeast of the modern hamlet of Alleaume, within the territory of the commune of Valognes, Manche department.[5] The theater, along with the baths to the north, represents the most prominent architectural feature of the ancient city. However, the forum in the center, several sanctuaries, and insulae occupied by residences are well-documented.

The results of studies conducted in 2012 and subsequent years have revealed the existence of a network of roads that traverse the ancient city, oriented in a north-northwest to east-northeast configuration. A contemporary route to the west of the theatre appears to follow the trajectory of the decumanus maximus, which, following a shift in its course, would have served the structure.[6] In its final section, the ancient road is paved with large stone slabs instead of a layer of pebbles, which may have been done to align with the significance of the monument it serves.[7] Another road bypasses the theater to the west and north. These roads possibly converged at the level of the theater on an esplanade covered with pebbles, providing access to its various entrances.[C 1]

The disparate orientation of the urban roads and the theater can be attributed to the aspiration to capitalize on the inherent topography of the terrain, which slopes predominantly towards the north-northwest for the city and north-northeast for the theater.[A 2]

History

[edit]The monument in ancient times

[edit]

The site of Alauna is referenced in two historical documents: the Peutinger table and the Antonine Itinerary.[A 3] In 1627, Nicolas Sanson proposed that this site corresponded to the locality of Alleaume.[A 4]

Nevertheless, the precise construction period of the theater remains undetermined based on the current state of knowledge. Additionally, there is not enough documented evidence regarding any potential plot occupation before its construction. Given that Alauna reached its maximum development between the end of the first and the end of the second century, it seems plausible that the city's monuments (theatre, baths, etc.) were constructed during this period, potentially at the outset. The spectacle building appears to have undergone a single campaign of modification or refurbishment, the date of which is undatable based on the available data, though it seems to have been of limited scope.[C 2]

The theater appears to have been operational until the third-century conclusion, although it is unlikely that it remained in use beyond that point.[8] Following its abandonment, the structure was repurposed as a stone quarry, a use that likely persisted for an extended period. This is evidenced by the discovery of ancient small rubble stones in the vicinity of nearby buildings that were constructed using these stones.[A 5] Additionally, a lime kiln was installed in the orchestra area after the theater was decommissioned. This kiln was likely employed to process the extracted stones.[C 3]

Historical mentions and studies in modern times

[edit]

The initial excavations were commissioned by Nicolas-Joseph Foucault, the intendant of the généralité of Caen. In the autumn of 1695, Pierre-Joseph Dunod, a Jesuit archaeologist, conducted excavations of the theater on the ground.[A 6] Subsequently, he published the plan in Mercure galant in December of the same year.[9] At that time, the theater appeared to be almost completely buried.[A 6] A second plan, markedly distinct from the initial one, was published in 1722 by Bernard de Montfaucon.[10] In the seventh volume of his Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises, Anne Claude de Caylus published in 1765 a drawing and plan of the theater, created by engineer René Cevet.[A 7][11]

In the early 1840s, Charles de Gerville resumed excavations at Alauna, thereby expanding the corpus of knowledge about the theater. He particularly mentioned the significant destruction that had affected the theater, which he surmised may have been perpetrated by Jean Cardine, the landowner between 1825 and 1835.[12] The Society of Antiquaries of Normandy continued Gerville's work in 1845[A 6] and indeed noted that for reasons of land leveling (for agricultural purposes) and to extract lime from removed stones,[13] the stage building and its arrangements, as well as the vomitoria walls, had been leveled.[14] The establishment of ditches and paths resulted in the dismantlement of a portion of the extant remains,[12] while the recovery of material artifacts continued for several decades.[C 2] Research activities then ceased, and until the 2000s, all publications about the theater merely reiterated, often without verification, the results of the previous excavations and their reports.[B 2]

The theater, like the entire archaeological site, was spared from the intense bombings that largely destroyed Valognes in June 1944 during the Battle of Normandy.[15][16]

In 2012, a new comprehensive investigation of the entire Alauna site was initiated. This entailed an inventory and reexamination of the bibliography, archaeological excavations or surveys, collection of artifacts, electrical prospection, and finally, ground-penetrating radar. In a bocage environment like this one, despite the remains being buried at a shallow depth, aerial prospection, which has previously revealed the ground traces of ancient buildings and arrangements in other situations, is less effective than in more open agricultural landscapes.[17] In this context, the theater was subjected to trench surveys in 2015[B 3] and ground-penetrating radar surveys in 2020.[18] These studies enabled the localization of the preserved remains, an assessment of their state of conservation, a partial but fundamental revision of the plan published by de Montfaucon, and an adjustment of the monument's orientation.[19][N 1]

Due to the exceptional rarity and burial of the remains, no specific enhancements have been made to the theater. However, guided tours of the entire archaeological site are conducted by the AAA association in collaboration with the Lands of ARt and History of Clos of Cotentin, particularly during the European Heritage Days. These tours include a stop at the theater site.[20]

Description

[edit]First sketches

[edit]

The excavations conducted in 1695, the plan created in 1722, and the surveys undertaken in the mid-1840s collectively provide an initial vision of the monument.

| Estimated capacity of the theater (number of spectators) |

|---|

The imprecision of certain excavation reports and published plans has resulted in a considerable range of estimates regarding the monument's capacity, with figures varying from 3,000 to 16,000 individuals.[B 2] This discrepancy can be attributed to the varying methodologies and assumptions employed by various authors. The most recent estimates, which fall within the lower range, align with the estimated population of Alauna, which is estimated to be between 3,000 and 4,000 inhabitants.[27]

The cavea, shaped like a horseshoe arch, has a diameter of 66 meters. The orchestra, in the shape of a horseshoe, has a diameter of 25 meters, while the narrow proscenium measures 19 meters in width. These characteristics classify the Alauna theater among Gallo-Roman amphitheaters, which were mixed-purpose structures capable of hosting various shows, with circus games in the orchestra and theatrical performances on the stage. The height differential between the summit of the cavea and the stage is estimated to be approximately eight meters.[28][29] Five vomitoria, whose walls were initially erroneously identified by Bernard de Montfaucon as "ten staircases [...] arranged in pairs, in parallel lines," provide access to all seating areas, from the peripheral wall to the orchestra.[30] At least two precinctions demarcate the boundaries of the cavea.[31]

New representations

[edit]The work carried out in the 21st century, including micro-topographic surveys by drone and approximately ten trench surveys in 2015, as well as georadar surveys over the entire presumed footprint of the monument in 2020, has resulted in a significant amendment to the plan published in 1722. This plan had been the foundation for all descriptions and interpretations until this revision.[C 2]

Rare above-ground remains, many reuses

[edit]A section of masonry (comprising small limestone rubble in regular courses) in a hedge separating two plots may have constituted a component of the annular wall of the theater, representing the sole above-ground remnant of this structure.[A 8] While the annular wall and the stage wall appear to have survived relatively intact, particularly in terms of their foundations, the theater interior has been largely destroyed, especially in the eastern section.[32]

The nearby manors, including the Castelet and Dingouvillerie, have likely incorporated a significant amount of the small rubble stones from the demolished ancient monument, as evidenced by local tradition. This reuse of ancient materials is similar to that observed in many modern constructions in the Alauna and Valognes areas, where stones from ancient structures have been used in the construction of buildings and boundary walls.[A 9]

A "mixed" monument built into the natural terrain

[edit]The theater is situated in a way that makes optimal use of the surrounding topography. It is built against the northwest-southeast slope of a talweg in the form of a half-basin, which helps to minimize the necessary earthworks to establish the cavea. Only the lower part of the theater is built on compacted clay and silt fills, which ensures the regularity of the stands' slope.[B 1]

It has been established that the entertainment complex in Alauna is equipped with a theatre of the arena variety, with a diameter of 72.7 meters.[C 4] Although the cavea does not extend beyond the semicircle, contrary to what Montfaucon's plan suggested by describing a horseshoe-shaped building, it opens onto a complete elliptical orchestra 24.2 meters wide (one-third of the building's diameter). This orchestra is served by two wide corridors parallel to the stage wall and accessible through clearly identified thresholds.[B 4] The stage building is of reduced dimensions and is equipped with buttresses on the exterior, as illustrated in the historical blueprints.[B 5] While the presence of a stage partially encroaching on the orchestra is a possibility, it has yet to be definitively confirmed.[C 4]

Optimized construction

[edit]The theater's foundations appear to be constructed of irregular limestone and sandstone blocks, held together by mortar. The stones are set in a trench and are of a greater width than the walls built on top of them. In one area of the monument where measurements were taken, the depth reached 0.95 meters.[C 5] The theater walls, which could be closely examined, consist of two facing layers of small local limestone rubble bound with mortar (opus vittatum), encasing a core of stones. It seems that opus mixtum, a technique that involves the interposition of layers of architectural terracotta between rows of rubble, was not employed in this instance.[B 6] In areas where the facings are not visible once the building is complete, for example in service corridors or at the base of walls buried in fill, the craftsmanship is less refined. This suggests that the technique was used to reduce construction times and make use of local resources.[C 6]

Specific structural elements are employed to reinforce the walls in areas where they are subjected to greater stress. The stage wall, for instance, is locally widened in its lower portions and equipped with buttresses, while masonry masses protrude at the thresholds at the ends of the stage wall.[C 7]

A socially organized cavea

[edit]

The results of recent surveys and prospections do not corroborate the presence of the precinction walls depicted on the 1722 plan.[N 2] The southern vomitorium appears to serve only the upper cavea, the two middle vomitoria the middle zone, and the two vomitoria closest to the stage wall the lowest stands near the orchestra. Spectators probably entered based on their social rank, with the closest seats to the orchestra occupied by the most prominent individuals.[33]

The square structure, axially positioned close to the orchestra but separated from it by the podium wall, is interpreted as an honorary box reserved for an important figure,[33] a common architectural feature observed in other entertainment buildings, such as at Cherré (Sarthe).[34]

The threshold and jambs of the middle vomitorium were uncovered during the 2015 surveys.[B 7] These jambs, which protrude outward, appear to serve a dual purpose, contributing to both the monument's aesthetic appeal and its structural integrity.[C 8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It has been demonstrated that the plan published by Dunod in 1695 was more accurate than Montfaucon's in 1722. This may be attributed to a superior interpretation of the 1695 observations, which were likely more practical soundings than generalized and thorough excavations.[C 2]

- ^ The precincts depicted on older plans may have been misinterpreted by contemporary archaeologists as structures erected after the construction of the theater. This could be evidenced by the presence of ditches and stone fillings.[C 3]

References

[edit]- Valognes (Manche - 50) « Alauna » - L'agglomération antique d'Alleaume - Prospection thématique 2012, Conseil général de la Manche, 2012:

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 63

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 215

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 17

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 26

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 128

- ^ a b c Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 27

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 35

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, p. 97

- ^ Jeanne, Duclos & Paez-Rezende 2012, pp. 119–141

- Agglomération antique d'Alleaume - La Victoire/Le Castelet - sondages programmés 3e année, DRAC/Conseil général de la Manche/INRAP, 2015:

- ^ a b Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, pp. 84–85

- ^ a b Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, pp. 79–83

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, p. 82

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, p. 105

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, pp. 87–89

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, pp. 87–98

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2015, pp. 108–109

- Agglomération antique d'Alleaume - La Victoire/le Castelet, géoradar et post-fouille 5e année : rapport 2017, DRAC Normandie/Conseil départemental de la Manche, 2018:

- ^ Jeanne 2018, pp. 217–218

- ^ a b c d Jeanne 2018, p. 219

- ^ a b Jeanne 2018, p. 217

- ^ a b Jeanne 2018, p. 220

- ^ Jeanne 2018, p. 213

- ^ Jeanne 2018, pp. 213–214

- ^ Jeanne 2018, pp. 214–215

- ^ Jeanne 2018, pp. 215–216

- Other references

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2013, p. 42

- ^ "Masse d'eau souterraine HG402 : Trias du Cotentin est et Bessin". sigessn.brgm.fr (in French). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Jeanne 2021, p. 29

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Jeanne & Duclos 2013, p. 15

- ^ Fichet de Clairefontaine 2004, p. 488

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Laurent (2020). "Valognes – Le Bas Castelet, Le Castelet". Archéologie de la France - Informations (in French). Archived from the original on February 11, 2022.

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2014). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume : La Victoire, le Castelet, sondages programmés 2e année : rapport 2014 (in French). Conseil général de la Manche/INRAP. pp. 51–53.

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2017). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume : La Victoire, le Castelet, post-fouille 4e année : rapport 2016 (PDF) (in French). Conseil général de la Manche/INRAP. p. 198.

- ^ Dunod, Pierre-Joseph (1695). "Plan du théâtre d'Alauna". Mercure de France (in French). Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ de Montfaucon, Bernard (1719). L'Antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (in French). Vol. III-2. Paris: Delaulne et associés. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ de Caylus, Anne Claude (1765). Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises (in French). Vol. VII. Desaint et Saillant. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Adam, Jean-Louis (1905). "Valognes". Cherbourg et le Cotentin / Congrès de l'Association française pour l'avancement des sciences (in French). E. Le Maout. pp. 589–590. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ Muller, Michel (2006). "Du vieux château au balnéaire, histoire des fouilles d'Alauna". Val'auna, revue historique sur Valognes et les alentours (in French) (9): 9.

- ^ Delalande 1846, p. 323

- ^ "Valognes : ville de ruines, les témoins se souviennent". Ouest-France (in French). June 19, 2014. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ Muller, Michel (2006). "Du vieux château au balnéaire, histoire des fouilles d'Alauna". Val'auna, revue historique sur Valognes et les alentours (in French) (9): 11.

- ^ Dubois, Jacques (2003). Archéologie aérienne : patrimoine de Touraine (in French). Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire: Alan Sutton. pp. 17–22. ISBN 2-84253-935-4.

- ^ Jeanne 2021, pp. 111–112

- ^ Jeanne 2021, p. 111

- ^ Gallier, Corinne (September 26, 2020). "Un triomphe pour le site antique". La Presse de la Manche (in French).

- ^ Dunod, Pierre-Joseph (1695). "Fouilles à Valognes". Le Mercure Galant (in French): 305. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ de Sainte-Marie, Pierre-Armand (1695). "Extrait d'une lettre écrite de Valognes en Basse-Normandie". Journal des sçavans (in French) (XXXVIII): 449. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ du Houguet, Pierre Mangon (1697). "Réflexions sur les découvertes faites à Valogne". Le Mercure Galant (in French): 67. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ de Caylus, Anne Claude (1765). Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises (in French). Vol. VII. Desaint et Saillant. p. 315. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ Démazure, Eugène (1959). Théâtre d'Alauna, gradination (in French). Eugène Démazure.

- ^ Macé, Jacques (1959). "Les ruines antiques d'Alauna, près de Valognes". Bulletin de la Société des antiquaires de Normandie (in French). LIV (1957-1958): 393.

- ^ "Archéologie : les fouilles révèlent la ville romaine d'Alauna". Ouest France (in French). August 8, 2014. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- ^ Fichet de Clairefontaine 2004, p. 489

- ^ Sear, Franck (2006). Roman Theatres : An Architectural Study. Oxford: OUP Oxford. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-19-814469-4. Archived from the original on July 4, 2024.

- ^ Coutil, Léon (1905). "Les Unelli, les Ambivariti et les Curiosolitæ". Bulletin de la Société normande d'études préhistoriques (in French). XIII: 145–147. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022.

- ^ de Gerville, Charles (1844). Monuments romains d'Alleaume (in French). Charles de Gerville. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2019). "Valognes – Agglomération antique d'Alauna". Archéologie de la France - Informations (in French). Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Jeanne 2021, p. 112

- ^ Lambert, Claude; Rioufreyt, Jean (1989). "Nouvelles fouilles : Aubigné-Racan". Dossiers de l'Archéologie (in French) (314 « Les théâtres de la Gaule romaine »): 78. ISSN 1141-7137.

Bibliography

[edit]- Delalande, Arsène (1846). "Rapport sur les fouilles exécutées à Valognes". Mémoires de la Société des antiquaires de Normandie (in French). XIV (1844): 317–331. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- Fichet de Clairefontaine, François (2004). "Valognes/Alauna". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France (in French) (25 « Capitales éphémères. Des Capitales de cités perdent leur statut dans l’Antiquité tardive, Actes du colloque Tours 6-8 mars 2003 »): 487–490. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline; Paez-Rezende, Laurent (2012). Valognes (Manche - 50) « Alauna » - L'agglomération antique d'Alleaume : Prospection thématique 2012 : document final de synthèse (in French). Vol. 1: Résultats. Conseil général de la Manche.

- Jeanne, Laurence (2018). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume : La Victoire/le Castelet, géoradar et post-fouille 5e année : rapport 2017 (PDF) (in French). DRAC Normandie/Conseil départemental de la Manche.

- Jeanne, Laurence (2021). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume - La Victoire/Le Castelet : géoradar 7e année : rapport 2020 (in French). Agglomération antique d'Alauna/Conseil général de la Manche.

- Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2013). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume - La Victoire : sondages programmés 1re année : Rapport 2013 (PDF) (in French). DRAC/Conseil général de la Manche/INRAP.

- Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2015). Agglomération antique d'Alleaume - La Victoire/Le Castelet : sondages programmés 3e année : Rapport 2015 (PDF) (in French). DRAC/Conseil général de la Manche/INRAP.

- Paez-Rezende, Laurent; Jeanne, Laurence; Duclos, Caroline (2021). "Actualité des recherches conduites sur l'édifice de spectacle de l'agglomération antique d'Alleaume (Alauna) à Valognes (Manche)". Aremorica (in French). 10: 25–50. doi:10.3406/aremo.2021.953. ISSN 1955-6713.

External links

[edit]- Architectural resource: "Theatrum" (in French). Archived from the original on July 31, 2024.

- "Page consacrée au théâtre". Agglomération antique d'Alauna (in French). Archived from the original on October 8, 2023.