23 March 1933 Reichstag speech

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

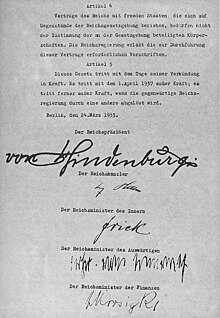

Adolf Hitler's March 1933 Reichstag speech as Chancellor is also known as the Enabling Act speech. Due to the Reichstag chamber being unusable following the fire on February 27/28, the speech took place in the Kroll Opera House.[1] This speech marked Hitler's second appearance before the Reichstag after the Day of Potsdam and led to a parliamentary vote that, for an initial period of four years, suspended the separation of powers outlined in the Weimar Constitution, effectively abolishing democracy in Germany.[1] The Enabling Act came into effect one day later.[1] The speech resembled a programmatic government declaration, encapsulating key elements of Nazi policy.

Course of the speech

[edit]For most parliamentarians, this was the first opportunity to see and hear Hitler in person, as this was Hitler's first appearance in the Reichstag.[2] Members of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) were not represented, as all its members were either in custody or in hiding,[1] while some members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) had also signed off on vacation.[2][3] SA and SS members present contributed to the intimidation of the parliamentarians.[2] The approximately 50-minute speech, delivered by Hitler in a brown shirt,[4] is noteworthy in retrospect for predicting the essential features of later Nazi policies, including the "Lebensraum" expansion policy, unitarization, the suppression of political opponents, the coordination (Gleichschaltung), and the departure from Roman law.

As the Chancellor appointed by the Reich President, Hitler requested and received parliamentary approval for this constitutional breach.[3]

The speech can be roughly divided into three parts: First, Hitler recapitulates the history of the German Reich from the November Revolution to the present, describing this development as illegitimate and holding it responsible for the crises and grievances in the Reich. Subsequently, in the longest part of the speech, he lists certain grievances as particularly urgent and explains how the Reich government under his leadership intends to address these problems. Finally, Hitler returns to the Enabling Act, explaining why it is necessary to effectively end the previously described Reich crisis.

The speech was rebutted by Otto Wels of the Social Democratic Party.[5] Hitler returned to the podium to rebut Wels; notably this was the only time after 1932 that Hitler took part in a public debate.[6]

History of the Reich

[edit]At the beginning of his speech, Hitler recaps the history of the German Reich, starting with the overthrow of the monarchical government under Kaiser Wilhelm II. during the November Revolution. In this revolution, "Marxist organizations" allegedly seized "executive power" by dethroning the monarch, "dismissing the imperial and state authorities," and thus "breaking the constitution." As the Marxists lacked the support of the German people for this act, they allegedly justified their actions with the "war guilt lie" – Hitler's term for the false claim that Germany alone was responsible for World War I. According to Hitler, the Marxists' misuse of the "war guilt lie" led to the subsequent "severe oppression of the German people," willingly accepted by the victorious powers of World War I. The German acknowledgment of the "war guilt lie" provided the opportunity for the victorious powers to impose harsh conditions on Germany through the "Versailles Dictate," initiating a "time of boundless misfortune" for the German people. Up to the present, all promises of the "November criminals" have proven to be "conscious deceptions" or at least "equally condemnable illusions," and the achievements of the revolution have been "infinitely sad" for the "overwhelming majority" of the people. The decline of the "political and economic inheritance" of the Reich could not recover even fourteen years after the proclamation of the Weimar Republic; instead, the "line of development continued downward." Despite government propaganda, the German people would increasingly recognize this failure and turn away from the responsible organizations and the Weimar Constitution. This became evident with the Reichstag election in March 1933, when the previously "terribly suppressed" National Socialists obtained a clear majority of 43.9%. Thus, the German people had given their approval to the "national revolution" and the elimination of the "powers ruling since November 1918."[4]

Grievances and program

[edit]In the second and longest part of the speech, Hitler presents his "Program for the Reconstruction of People and Reich" and introduces the grievances primarily responsible for the "great distress in our political, moral, and economic life."[4]

Eradication of Marxism

[edit]To achieve and maintain the future stability of the Reich, its "internal enemies" must be eliminated first, meaning "those who would prevent any actual resurgence for the future." Hitler explicitly refers to the Marxists, whom he holds responsible for the decline in the introduction. The "Marxist false doctrine" preaches the "permanent revolution against all [ideological] foundations of our communal life to date" and inevitably ends "naturally in communist chaos." According to Hitler, an increasing number of citizens are willing to commit serious crimes "in the service of the communist idea" – that is, for a communist revolution modeled after the Soviet Union. The "arson in the Reichstag building" was the preliminary climax, not only endangering Germany but all of Europe.[4]

To prevent the "communist chaos," the Reich must ruthlessly proceed against its internal enemies. Hitler strongly advocates atoning for the Reichstag fire "through the public execution of the guilty arsonist and his accomplices" – the accomplices being several members of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), whose support Hitler was convinced of against the prevailing knowledge at the time.[4]

To completely eradicate and eliminate the communists "in our country," it is not only necessary to take violent action against them; the "German worker" must also be enthused for the "national state." Only the "establishment of a real national community" can ensure a stable society. In other words, divisive, dangerous socialism according to the KPD and SPD is insufficient because it fails to recognize that different classes and estates pursue different interests. These can only become a cohesive "national body" through their race, ensuring a stable society.[4]

Weakening of federalism

[edit]

The stability of the Reich is also threatened by an increasing "weakening of the authority of the highest state leadership (Reich government)." Hitler specifically refers to preceding Reich governments that often lasted only a few months (e.g., the Papen Cabinet) or even just a few weeks (e.g., the Schleicher Cabinet). The longest-serving cabinet was the Müller II Cabinet, with just 1 year and 272 days. This instability is attributed to powerful federal states within the Reich, possessing "ideas that are incompatible with the unity of the Reich." Hitler mentions instances where prime ministers, using modern political propaganda, disparaged other federal states and the Reich, weakening German authority abroad.[4] In the historical context, Hitler likely referred to Otto Braun, the former Prime Minister of Prussia, who was effectively ousted by the Reich government under Franz von Papen following the Preußenschlag. Braun, discontented with this coup, expressed his displeasure both through Reich broadcasting and foreign magazines.[citation needed]

The well-being of the states depends on the strength and health of the Reich, and the "spiritual and volitional unity of the nation and thus the concept of the Reich itself" is impossible if there is not "uniformity of political intentions in the Reich and in the states."[4]

The Enabling Act is not intended to "abolish the states." Respect for the traditional values of the states should be taken into account. Only transitional measures need to be taken to realign the Reich and the states. The greater the spiritual and volitional agreement, the less interest there will be in "violating the cultural and economic life of individual states."[4]

Co-opting of the press and media

[edit]To guarantee the necessary "national body" for stability, the Reich government must undertake a "moral purification." The entire education system, especially theater, film, literature, the press, and radio, must be directly led and controlled by the government. Although Hitler did not use the term, the later societal coordination (Gleichschaltung) is undoubtedly meant by "moral purification" through full state control of the media. Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels stated on March 25, 1933, just one day after the Enabling Act came into effect:

"The radio is being cleansed. [...] We make no secret of it: the radio belongs to us, no one else. And we will put the radio in the service of our idea, and no other idea shall have a voice here."[4]

Hitler exemplifies his vision of "spiritual detoxification" in art: depressing realism must be eliminated and replaced with "heroism" because, especially in times of limited political power, the inner value and will to live of the nation need a more powerful cultural breakthrough. To give the people new strength and motivation through heroism, constant education about the "great past" of the Reich is necessary. Thus, German youth should be instilled with "awe for the great men" such as Bismarck and Wilhelm II. To achieve the pursued goal of a "national body," the source of artificial intuition must be "blood and race."

Friendly Relations with Christian Churches

[edit]Because the "most important factors for preserving our national identity" lie in the two Christian denominations, the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches, the Reich government wants to engage with them in friendly relations. Compromises with atheist organizations are to be reversed. Christianity, in its "struggle against a materialistic worldview and for the establishment of a real national community," pursues the same goals as National Socialism and, therefore, enjoys the protection of the government. However, the church is reminded that "affiliation with a particular denomination" does not exempt it from "general legal obligations." If it opposes the "national uprising," it will be fought against.[4]

Judicial reform

[edit]Because the legal system should primarily serve the preservation of the national community, the focus of the law should be on "not the individual [...], but the people." In alignment with Point 19 of the 25-Point Program, where the NSDAP demands the "replacement of Roman law, serving the materialistic world order, with a German common law," Hitler accuses the judiciary of promoting egoism and weakening the national community by prioritizing their individual interests over the interests of the people. He emphasizes his rejection of the rule of law by stating that justice must, to make fair individual decisions, not be guided by positive law but by natural law. In other words, written law should not be binding when its application would lead to a result harmful to the national community. Thus, "the flexibility of judgment for the purpose of preserving society" must be ensured.[4]

Hitler rejects the liberalization of jurisprudence that, during the Weimar Republic, increasingly turned to the special preventive theories of Franz von Liszt. Instead, high treason and state treason should be "burned out with barbaric ruthlessness," advocating a return to the retributive and general preventive theories of previous epochs.[4] This philosophy aligns with the later NS special courts, such as the establishment of the People's Court on April 24, 1934, for the judgment of high treason and state treason.

Economic policy: Strengthening workers and protectionism

[edit]Extensive economic reforms are aimed at saving two population groups: the middle class and the German peasantry. The latter must be saved from bankruptcy because agriculture is the most important source for German domestic trade and exports; the collapse of agriculture would lead to the "collapse of the German economy as a whole." Culturally, the peasantry has presented itself as a "counterweight" to communism, without which "communist madness would have overrun Germany." To support these groups and reintegrate the nearly five million unemployed Germans into the production process, work must be rewarding and serve the racial whole. This is to be ensured through land reforms and the guarantee of private property for the worker. A comprehensive tax reform should burden primarily the upper class, not small business owners. By decentralizing state administration to reduce public burdens for citizens, public administration will be simplified. "Currency experiments" are to be rejected, advocating for the preservation of the Reichsmark and against the policies of former Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, who introduced the transitional currency Rentenmark in 1923. Stresemann had previously been the target of Nazi ridicule, especially for his marriage to a Jew - Käte Kleefeld. State interventionism should ensure "the increase of purchasing power" of the middle and peasant class. Market processes should be modified wherever necessary; the Reich government will intervene economically "even if the measures cannot count on popularity at the moment."[4] Thus, the government intends to introduce "mandatory labor service," implemented in June 1935 by the Reich Labor Service.

Hitler advocates protectionism and rejects a market economy with freely determined market prices. The Reich government is not inherently "export-hostile" and recognizes that "the geographical location of resource-poor Germany does not allow complete autarky for our Reich." Germany's fragile situation has been exploited by the victorious powers to demand "services without reciprocation." As long as reparations payments according to Article 231 of the Versailles Treaty are not reduced, the Reich feels compelled to enforce "foreign exchange control." Hitler hopes that consistent adherence to a protectionist course will lead the victorious powers to lower their reparations demands, expecting Germany to re-enter the international market.[4]

Comprehensive nationalization of personal transport and civil service

[edit]Through state interventions, a hierarchy of different modes of transportation is intended to be guaranteed. The use of motor vehicles should be made less attractive by increasing the motor vehicle tax, while the German Reichsbahn (German Imperial Railway), which was managed by the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft under the Dawes Plan, is to be nationalized. Additionally, air traffic, seen as a "means of peaceful connection among peoples," must become state property. The professional civil service must be more closely linked to the Reich government and contribute "dedicated loyalty and work." Autonomous action in this regard is only legitimate "in cases of compelling necessity given the state of public finances."[4]

Rearmament of the Reichswehr

[edit]The Reichswehr declared Hitler as the guarantor of the "protection of the borders of the Reich and thus the life of the people," considering it the bearer of their best military traditions. The German people had diligently fulfilled their obligations under the Treaty of Versailles, radically limiting the army to only 100,000 men. However, Hitler argued that, in return, other nations had repeatedly promised to disarm, a promise they had never kept. The Geneva Disarmament Conference had been ongoing for fourteen months without producing any results. While acknowledging the goodwill efforts of British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald to advance the conference, Hitler stated that every attempt had been in vain, delayed by technical issues and unrelated problems:

"For fourteen years, we have been disarmed, and for fourteen months, we have been waiting for results from the Disarmament Conference."[4]

Hitler expressed the sincere desire of the national government to refrain from increasing the German army but insisted that for national security, equality must be ensured. He emphasized that Germany sought nothing more than equal rights and freedom. The mindset of the Treaty of Versailles, dividing nations into victors and vanquished, needed to be eliminated for peaceful coexistence among nations:

"The national government is ready to extend a sincere hand of understanding to any people willing to finally fundamentally close the sad past. The world's distress can only diminish if trust is restored within and between nations through stable conditions."[4]

Hitler declared his readiness to disarm radically if other nations followed suit. As long as this did not happen, a "unlawful state of unilateral disarmament and the resulting national insecurity of Germany" would persist. In such a situation, Germany, contrary to its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles, would have to rearm the Reichswehr.[4]

Foreign policy

[edit]The program concluded with remarks on foreign policy. Hitler expressed gratitude to the fascist dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini, for negotiating peaceful coexistence between Germany and the victorious powers. Hitler was particularly thankful for the "understanding warmth with which the national uprising of Germany has been welcomed in Italy" and hoped to build on these shared ideals. This collaboration eventually led to the signing of the Pact of Steel and the formation of the Rome-Berlin Axis, which fought against the Allies in World War II.[4]

Stressing that the national government saw "Christianity as the unshakable foundations of the moral and ethical life" of the people, Hitler pledged to maintain and strengthen friendly relations with the Holy See. This declaration received applause, especially from members of the Center Party. The Reichskonkordat, signed in July 1933, for this purpose is still valid today. Despite its political orientation, the Reich government wanted to maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union because "the struggle against communism in Germany is our internal affair." However, interference from the Soviet Union in this internal matter would not be tolerated.[4] These relatively conciliatory words contradicted Hitler's previous statements in his programmatic writings, Mein Kampf (1923) and his Second Book, where he declared a "conquest and annihilation war against the Soviet Union" as the main goal of his foreign policy. In these writings, he asserted that "Bolshevism" was the most extreme form of rule by "world Jewry," and Germany could only find its permanent "living space" in the East ("Lebensraum im Osten").[citation needed]

Hitler expressed a willingness to have peaceful exchanges with the victorious powers. However, he emphasized that for this to happen, these powers needed to abandon the "distinction between victors and vanquished"—in other words, move beyond the Treaty of Versailles.[4] The Reich government saw the upcoming London Economic Conference as a first step toward peaceful understanding and pledged strong support for the initiative.

Finally, Hitler addressed the "brother nation" of Austria and other "German tribes." In alignment with the illegitimacy of the Treaty of Versailles and the Nazi philosophy of "living space," the Reich government acknowledged its awareness of the interconnected fate of all German tribes. Germany would, if necessary, use force to secure "the fate of Germans outside the borders of the Reich, fighting for the preservation of their language, culture, customs, and religion as special ethnic groups within foreign nations."[4] In these explicit words, one can find an announcement of Hitler's later expansionist policies, as seen in the annexation of Austria in 1938 and the annexation of Czechoslovakia during the Sudeten Crisis, justified by claiming to protect the autonomy of the "oppressed" Sudeten Germans.

Necessity of the Enabling Act

[edit]After comprehensively outlining the programmatic agenda, Hitler returns to the Enabling Act, emphasizing its necessity for swiftly and effectively implementing ambitious goals. He argues that too much parliamentary deliberation and discussion would impede progress, preventing Germany from addressing its issues.[4]

Furthermore, Hitler asserts that ensuring a stable government is crucial for the desired stability of the Reich. The authority of preceding governments had suffered due to their fragility, diminishing their standing among the people. A decisive and sovereign government is impossible, he argues, if it has to constantly seek approval from the Reichstag for its actions:

"The authority and thus the fulfillment of the government's tasks would suffer if doubts about the stability of the new regime could arise among the people."[4]

Hitler then addresses concerns about unchecked authority and stability, assuring that the Reichstag will not be dissolved. Instead, the government reserves the right to inform the Reichstag of its measures and, if necessary, seek its approval for specific reasons. The Enabling Act should be seen as a kind of emergency law, applicable only "to implement vital measures."[4]

The speech concludes with Hitler referring to the approval from the German people. He highlights the disciplined and bloodless nature of the "national uprising" of the Nazi Party. Germany has finally experienced calm conditions, which the divided Reichstag could never guarantee. Hitler appeals to the Reichstag to pass the law, enabling a "peaceful German development" in the future. However, he warns that if the Reichstag opposes it, he is "equally determined and ready to accept the expression of rejection and the announcement of resistance." The speech concludes with the words:

"May you, gentlemen, now make the decision yourselves about peace or war."[4]

The audience then responded with ovations, and sang the Deutschlandlied whilst standing.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Parliament lost – DW – 03/23/2013". dw.com. Retrieved 2023-11-18.

- ^ a b c "Hitlers Machtübernahme im Parlament" [Hitler's rise to power in parliament]. SWR Kultur (in German). 2023-07-13. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ a b "Verhandlungen des Reichstags VIII Wahlperiode 1933" [Negotiations of the Reichstag VIII electoral period 1933]. Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstags (in German). Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Domarus, M.; Hitler, A.; Gilbert, M.F. (1990). Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations 1932-1945. 1932-1934. Vol. 1 (PDF). Tauris. pp. 275–285. ISBN 978-1-85043-206-7. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ "Otto Wels". Holocaust Encyclopedia. 1933-01-30. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ Domarus, M.; Hitler, A.; Gilbert, M.F. (1990). Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations 1932-1945. 1932-1934. Vol. 1 (PDF). Tauris. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-85043-206-7. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ Fergusson, Gilbert (1964). "A Blueprint for Dictatorship. Hitler's Enabling Law of March 1933". International Affairs. 40 (2). [Wiley, Royal Institute of International Affairs]: 245–261. doi:10.2307/2609908. ISSN 1468-2346. JSTOR 2609908. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

Amid wild applause from his followers, Hitler stepped down from the rostrum. The Nazis sang the Deutschlandlied...