Doug Jones (politician)

Doug Jones | |

|---|---|

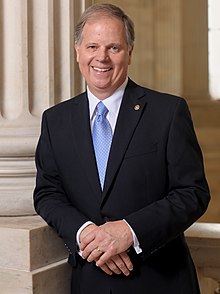

Official portrait, 2018 | |

| United States Senator from Alabama | |

| In office January 3, 2018 – January 3, 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Luther Strange |

| Succeeded by | Tommy Tuberville |

| United States Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama | |

| In office September 8, 1997 – January 20, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Claude Harris Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Alice Martin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gordon Douglas Jones May 4, 1954 Fairfield, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Louise New (m. 1992) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | University of Alabama (BS) Samford University (JD) |

| Signature | |

| Website | Campaign website |

Gordon Douglas Jones (born May 4, 1954) is an American attorney and politician who served as a United States senator from Alabama from 2018 to 2021.[1][2] A member of the Democratic Party, Jones was previously the United States Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama from 1997 to 2001. He is the most recent Democrat to win and/or hold statewide office in Alabama.

Jones was born in Fairfield, Alabama, and is a graduate of the University of Alabama and Cumberland School of Law at Samford University. After law school, he worked as a congressional staffer and as a federal prosecutor before moving to private practice. In 1997, President Bill Clinton appointed Jones as U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama. Jones's most prominent cases were the successful prosecution of two Ku Klux Klan members for the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four African-American girls and the indictment of domestic terrorist Eric Rudolph. He returned to private practice at the conclusion of Clinton's presidency in 2001.

Jones announced his candidacy for United States Senate in the 2017 special election following the resignation of Republican incumbent Jeff Sessions to become U.S. Attorney General. After winning the Democratic primary in August, he faced former Alabama Supreme Court Justice Roy Moore in the general election. Jones was considered a long-shot candidate in a deeply Republican state. A month before the election, Moore was alleged to have sexually assaulted and otherwise acted inappropriately with several women, including some who were minors at the time.[3] Jones won the special election by 22,000 votes, 50%–48%.[4]

At the time, Jones was the only statewide elected Democrat in Alabama and the first Democrat to win statewide office since Lucy Baxley was elected President of the Alabama Public Service Commission in 2008. Democrats had not represented Alabama in the U.S. Senate since 1997, when Howell Heflin left office. Jones was considered a fairly moderate Democrat, who supported reproductive and LGBT rights but demonstrated a willingness to work with Republicans and split with his party on certain issues.[5] Jones ran for a full term in 2020 and lost to Republican nominee Tommy Tuberville in a landslide. His margin of defeat was the largest of an incumbent senator since 2010.[6]

In January 2021, he joined CNN as a political commentator.[7] Jones was a fellow at the Georgetown University's Institute of Politics and Public Service during the spring 2021 academic semester, and was a distinguished Pritzker Fellow at the University of Chicago's Institute of Politics during the fall of 2022.[8] In February 2022, the Biden administration named him as a nomination advisor for legislative affairs, advising the president on Supreme Court nominations.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Doug Jones was born in Fairfield, Alabama to Gordon and Gloria (Wesson) Jones.[9][10] His father worked at U.S. Steel and his mother was a homemaker.[11] He went to Fairfield High School.[12] Jones graduated from the University of Alabama with a Bachelor of Science in political science in 1976, and earned his Juris Doctor from Cumberland School of Law at Samford University in 1979. He is a member of Beta Theta Pi.[13]

Jones's political career began as staff counsel to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee for Alabama Senator Howell Heflin.[14] Jones then worked as an Assistant U.S. Attorney from 1980 to 1984 before resigning to work at a private law firm in Birmingham, Alabama, from 1984 to 1997.[15] He ran in the Democratic primary for district 6 of the Alabama House of Representatives in 1994, but did not advance to the runoff.[16]

Career

[edit]President Bill Clinton announced on August 18, 1997, his intent to appoint Jones as U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama,[17] and formally nominated Jones to the post on September 2, 1997.[18] On September 8, 1997, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama appointed Jones as interim U.S. Attorney. The Senate confirmed Jones' nomination on November 8, 1997,[18] by voice vote.[19]

In January 1998, Eric Rudolph bombed the New Woman All Women Health Care Center in Birmingham. Jones was responsible for coordinating the state and federal task force in the aftermath, and advocated that Rudolph be tried first in Birmingham before being extradited and tried in Georgia for his crimes in that state, such as the Centennial Olympic Park bombing.[20][21]

16th Street Baptist Church bombing case

[edit]

Jones prosecuted Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr. and Bobby Frank Cherry, two members of the Ku Klux Klan, for their roles in the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. The case was reopened the year before Jones was appointed, but did not gain traction until his appointment. A federal grand jury was called in 1998, which caught the attention of Cherry's ex-wife, Willadean Cherry, and led her to call the FBI to give her testimony. Willadean then introduced Jones to family and friends, who reported their own experiences from the time of the bombing. A key piece of evidence was a tape from the time of the bombing in which Blanton said he had plotted with others to make the bomb. Jones was deputized to argue in state court and indicted Blanton and Cherry in 2000.[22][23] Blanton was found guilty in 2001 and Cherry in 2002. Both were sentenced to life in prison. Cherry died in prison in 2004.[24] Blanton was up for parole in 2016; Jones spoke against his release, and parole was denied.[25] Blanton died in prison in 2020.[26]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Jones recounts the history of the bombings and his subsequent involvement in Blanton and Cherry's prosecution in his 2019 book Bending Toward Justice: The Birmingham Church Bombing that Changed the Course of Civil Rights.[27]

Return to private practice

[edit]Jones left office in 2001 and returned to private practice, joining the law firm of Haskell Slaughter Young & Rediker.[28] In 2004, he was court-appointed General Special Master in an environmental cleanup case involving Monsanto in Anniston, Alabama.[29][30][31] In 2007, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute gave Jones its 15th Anniversary Civil Rights Distinguished Service Award.[32] Also in 2007, Jones testified before the United States House Committee on the Judiciary about the importance of reexamining crimes of the Civil Rights Era.[33][34] In 2013, he formed the Birmingham firm Jones & Hawley, PC with longtime friend Greg Hawley.[29] Jones was named one of B-Metro Magazine's Fusion Award winners in 2015.[35] In 2017, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Alabama chapter of the Young Democrats of America.[36]

U.S. Senate

[edit]Elections

[edit]2002

[edit]On August 15, 2001, Jones announced an exploratory candidacy for U.S. Senate against incumbent Jeff Sessions in 2002.[37] Jones said he was running because "We've hardly seen Jeff Sessions in the last four years...I'm going to be here to work for the people of Alabama."[38] Despite his successful prosecution of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing case, Jones was not well-known statewide and had low name recognition.[39] He ended his campaign February 18, 2002, citing difficulties raising money.[40]

2017

[edit]

On May 11, 2017, Jones announced his candidacy for that year's U.S. Senate special election, running for the seat left open when Sessions was appointed Attorney General. Sessions, a Republican, had held the seat since 1997, after Democrat Howell Heflin chose not to run for reelection.[41] Jones won the Democratic nomination in August,[42] and became the senator-elect for Alabama after defeating former Alabama Supreme Court judge Roy Moore in the general election on December 12, which was also Jones's 25th wedding anniversary.[43][44]

Jones received 673,896 votes (50.0%) to Moore's 651,972 votes (48.3%) with 22,852 write-in votes (1.7%).[43] After the election, Moore refused to concede. He filed a lawsuit attempting to block the state from certifying the election and called for an investigation into voter fraud, as well as a new election.[45] On December 28, 2017, a judge dismissed his suit and state officials certified the election results, officially declaring Jones the winner.[46]

2020

[edit]

Jones ran for a full six-year term. He was seen as the most vulnerable senator from either party since Alabama is a deeply Republican state and the circumstances and controversy surrounding his Republican opponent in 2017 were no longer a factor.[47]

The Democratic Party nominated Jones for the seat unopposed.[48] The two top contenders in the Republican primary were former football coach Tommy Tuberville and former United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who had held Jones's seat before resigning to become attorney general in 2017. U.S. Representative Bradley Byrne was also a contender, sometimes even outpolling the other candidates, but in the first round of the primary, on March 3, Tuberville and Sessions finished second and first. Since neither had a majority of the vote, they advanced to a runoff, which Tuberville won.

Tuberville won the general election with over 60% of the vote.[49][50] Jones was the only Democratic senator to lose re-election in 2020.[51]

Tenure

[edit]Jones was sworn in on January 3, 2018, alongside fellow Democrat Tina Smith of Minnesota, and his term ran through January 3, 2021, the balance of Sessions's term.[52][53] He was the first Democrat to represent the state in the U.S. Senate in 21 years, and the first elected in 25.[54][55] Jones was one of five Democratic senators who voted for the continuing resolution that failed to pass and consequently led to the January 2018 United States federal government shutdown.[56] According to Morning Consult, which polls approval ratings of senators, as of October 17, 2019[update], Jones had a 41% approval rating, with 36% disapproving. This trailed Jones's fellow Alabama senator, Republican Richard Shelby, who had a 45% approval rating, with 30% disapproving.[57]

On January 8, 2019, Jones was one of four Democrats to vote to advance a bill imposing sanctions against the Syrian government and furthering U.S. support for Israel and Jordan as Democratic members of the chamber employed tactics to end the United States federal government shutdown of 2018–2019.[58]

In September 2019, after the House launched an impeachment inquiry against President Trump, Jones urged caution on the part of the media and his colleagues because his experience with law had led him to believe that it was "very unlikely there's going to be an absolute smoking gun on either side". He stated his support for "fact-finding" by the House, only after which he would make a decision about Trump's guilt.[59][60] In February 2020, Jones voted to convict President Donald Trump in his impeachment trial, saying the evidence presented "clearly proves" that Trump used his office to seek to coerce a foreign government to interfere in the election.[61]

Committee assignments

[edit]- Committee on Armed Services

- Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs[62]

- Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

- Special Committee on Aging

- Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Post-congressional career

[edit]

In November 2020, Jones was mentioned as a potential candidate for United States Attorney General in the Biden administration.[63] The position was ultimately filled by Merrick Garland.

On January 29, 2021, Jones joined CNN as a political commentator. He also became a politics fellow at Georgetown University.[64] In May 2021, Jones and his former Senate staff member Cissy Jackson were announced to have joined the Government Relations and Government Enforcement & White Collar division of the D.C.-based law firm Arent Fox, joining the likes of former senator Byron Dorgan and former representative Phil English.[65]

In January 2022, Biden named Jones as his "sherpa" in assisting with the nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court vacancy, filling the vacancy created by the announced retirement of Stephen Breyer.[66][67] Jackson was confirmed by a 53–47 vote on April 7, 2022.[68]

Political positions

[edit]The editorial board of The Birmingham News has described Jones as a "moderate Democrat".[69] Former Alabama Democratic Party chair Giles Perkins described Jones as "a moderate, middle-of-the-road guy".[70] Describing his own views, Jones said: "If you look at the positions I've got on health care, if you look at the positions I got on jobs—you should look at the support I have from the business community—I think I'm pretty mainstream."[71] Jones's campaign has emphasized "kitchen-table" issues such as health care and the economy.[72][73][74] He has called for bipartisan solutions to those issues[75] and pledged to "find common ground" between both major parties.[76] Jones said that people should not "expect [him] to vote solidly for Republicans or Democrats".[77] During his campaign, he had supporters from both parties, including Republican senator Jeff Flake of Arizona.[78][79] According to FiveThirtyEight, Jones had voted with President Donald Trump's position about 35% of the time as of September 2020.[80]

A July 2018 NBC News editorial stated that Jones had voted with Trump more often than all but three of his fellow Democratic senators (Joe Manchin, Heidi Heitkamp and Joe Donnelly) while also taking liberal positions more in line with his party, including LGBT rights.[81]

Abortion

[edit]Jones is mostly pro-choice on abortion with the exception of late-term abortion stating during a virtual rally "I have never, never supported what is known as a late term abortion." Also in the same virtual rally he stated "I support the Hyde Amendment I have said that over and over." In 2018, Planned Parenthood gave him a 100% rating, while the National Right to Life Committee gave him a 0% rating. Jones voted against the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, which prohibits abortion after 20 weeks except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the pregnant woman's health.[82] He also pledged to support Planned Parenthood as a senator.[83] In May 2019 he criticized the passage of an abortion ban in Alabama, calling it "shameful".[84]

In February 2019, Jones was one of three Senate Democrats to vote for the Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act, legislation requiring health care practitioners present at the time of a birth "exercise the same degree of professional skill, care, and diligence to preserve the life and health of the child as a reasonably diligent and conscientious health care practitioner would render to any other child born alive at the same gestational age."[85]

Agriculture

[edit]On December 11, 2018, Jones voted for the conference farm bill, which included his provisions for farmers, rural health, wastewater infrastructure, and high-speed internet.[86] In May 2019, he co-sponsored the Transporting Livestock Across America Safely Act, a bipartisan bill introduced by Ben Sasse and Jon Tester intended to reform hours of service for livestock haulers by authorizing drivers to have the flexibility to rest at any point during their trip without it being counted against their hours of service and exempting loading and unloading times from the calculation of driving time.[87]

Broadband

[edit]In June 2019, Jones and Republican senator Susan Collins cosponsored the American Broadband Buildout Act of 2019, a bill that requested $5 billion for a matching funds program that the Federal Communications Commission would administer to "give priority to qualifying projects" and mandated that at least 15% of funding go to high-cost and geographically challenged areas. The legislation also authorized recipients of the funding to form "public awareness" and "digital literacy" campaigns to further awareness of the "value and benefits of broadband internet access service" and served as a companion to the Broadband Data Improvement Act.[88]

Criminal justice reform

[edit]In December 2018, Jones voted for the First Step Act, legislation aimed at reducing recidivism rates among federal prisoners by expanding job training and other programs in addition to expanding early-release programs and modifying sentencing laws such as mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders, "to more equitably punish drug offenders."[89]

Jones supports the reversal of mandatory three-strikes laws for nonviolent offenses to give judges flexibility in giving sentences.[73]

Corporate disclosure

[edit]In June 2019, along with Democrat Mark Warner and Republicans Tom Cotton and Mike Rounds, Jones introduced the Improving Laundering Laws and Increasing Comprehensive Information Tracking of Criminal Activity in Shell Holdings (ILLICIT CASH) Act, a bill mandating that shell companies disclose their real owners to the United States Department of the Treasury and updating outdated federal anti-money laundering laws by bettering communications among law enforcement, regulatory agencies, the financial industry, and the industry and regulators of advanced technology. Jones said he was "all too familiar with criminals hiding behind shell corporations to enable their illegal behavior" from being an attorney.[90]

Defense

[edit]In March 2018, Jones voted against Bernie Sanders's and Chris Murphy's resolution to end U.S. support for the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.[91]

In an interview with The Birmingham News, Jones said he favored increasing defense spending, saying it would boost Alabama's local economy, particularly in the areas around NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and the U.S. Army's Redstone Arsenal, and protect the United States from foreign threats.[92]

Jones voted to confirm Mike Pompeo as U.S. Secretary of State, joining with Republicans and five other Democratic senators. He opposed Gina Haspel's nomination as CIA director.[93]

In May 2019, Jones co-sponsored the South China Sea and East China Sea Sanctions Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced by Marco Rubio and Ben Cardin intended to disrupt China's consolidation or expansion of its claims of jurisdiction over the sea and air space in disputed zones in the South China Sea.[94]

In August 2019, after Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar were denied entry into Israel due to their support for BDS, Jones said he was "concerned the relationship with Israel is beginning to see some cracks for political reasons" and that the US-Israel relationship was being "used as a political weapon to try to divide people for political gain" in both countries. He added that while he did not agree "with a lot of their views on Israel", Tlaib and Omar were entitled to them, and cited the necessity of having to defend other members of Congress when they are barred from "the right to go and visit with other members".[95]

In October 2019, Jones was one of six senators to sign a bipartisan letter to President Trump calling on him to "urge Turkey to end their offensive and find a way to a peaceful resolution while supporting our Kurdish partners to ensure regional stability" and arguing that to leave Syria without installing protections for American allies would endanger both them and the US.[96]

Economy

[edit]Newsweek has described Jones as an economic populist.[97] He was one of five Democrats to vote for the Republican budget deal in January 2018[98] and one of 17 Democrats to vote with Republicans in favor of a bill to ease banking regulations.[99] Jones opposes the tariffs imposed by the first Trump administration.[100]

Education

[edit]In February 2019, Jones was one of 20 senators to sponsor the Employer Participation in Repayment Act, enabling employers to contribute up to $5,250 to the student loans of their employees.[101]

In July 2019, Jones and Tina Smith introduced the Addressing Teacher Shortages Act, a bill to allow school districts across the United States to apply for grants to aid the schools in attracting and retaining quality teachers. The bill also funded the Education Department's efforts to help smaller and under-resourced districts apply for grants.[102]

On September 19, 2019, Jones took to the Senate floor to request unanimous consent to pass legislation that would further the $255 million in federal funding for minority-serving colleges and universities ahead of its expiration date in weeks. The vote was shut down by Senate Education Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander, who instead called for support for the passage of "a long-term solution that will provide certainty to college presidents and their students" and "a few additional bipartisan higher education proposals."[103]

Environment

[edit]In March 2019, Jones was one of three Democrats to vote with all Senate Republicans against the Green New Deal when it came up for a procedural vote. All other Senate Democrats voted "present" on the legislation, a move anticipated as allowing them to avoid having a formal position.[104]

In June 2019, Jones was one of 44 senators to introduce the International Climate Accountability Act, legislation that would prevent Trump from using funds in an attempt to withdraw from the Paris Agreement and directing the Trump administration to instead develop a strategic plan for the United States that would allow it to meet its commitment under the Paris Agreement.[105]

Gun policy

[edit]Jones supports some gun control measures, including "tighter background checks for gun sales and to raise the age requirement to purchase a gun from 18 to 21",[106] but has said that he does not support an assault weapons ban and that such a ban could not pass Congress.[107] Jones himself is a gun owner.[108]

In March 2018, Jones was one of 10 senators to sign a letter to Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Lamar Alexander and ranking Democrat Patty Murray requesting they schedule a hearing on the causes and remedies of mass shootings in the wake of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting.[109]

In 2018, Jones co-sponsored the NICS Denial Notification Act,[110] legislation developed in the aftermath of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting that would require federal authorities to inform states within a day after a person failing the National Instant Criminal Background Check System attempts to buy a firearm.[111]

Healthcare

[edit]Jones opposes the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, but he has called for changes to the U.S. health-care system, which he calls broken.[112] He supports the reauthorization of the Children's Health Insurance Program[112] and during his senatorial campaign repeatedly criticized his opponent for lacking a clear stance on the program.[112][75] Jones says he is open to the idea of a public option, but that he is "not there yet" on single-payer healthcare.[73] In January 2018, Jones was one of six Democrats to join most Republicans in voting to confirm Alex Azar, Trump's nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services.[113]

In December 2018, Jones was one of 42 senators to sign a letter to Trump administration officials Alex Azar, Seema Verma, and Steve Mnuchin arguing that the administration was improperly using Section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act to authorize states to "increase health care costs for millions of consumers while weakening protections for individuals with preexisting conditions". The senators requested the administration withdraw the policy and "re-engage with stakeholders, states, and Congress".[114]

In January 2019, Jones was one of six senators to cosponsor the Health Insurance Tax Relief Act, delaying the Health Insurance Tax for two years.[115]

In January 2019, Jones was one of six Democratic senators to introduce the American Miners Act of 2019, a bill that would amend the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 to swap funds in excess of the amounts needed to meet existing obligations under the Abandoned Mine Land fund to the 1974 Pension Plan as part of an effort to prevent its insolvency as a result of coal company bankruptcies and the 2008 financial crisis. It also increased the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund tax and ensured that miners affected by the 2018 coal company bankruptcies would not lose their health care.[116]

In January 2019, during the 2018–19 United States federal government shutdown, Jones was one of 34 senators to sign a letter to Commissioner of Food and Drugs Scott Gottlieb recognizing the efforts of the FDA to address the effect of the government shutdown on public health and employees while remaining alarmed "that the continued shutdown will result in increasingly harmful effects on the agency's employees and the safety and security of the nation's food and medical products".[117]

In February 2019, Jones was one of 11 senators to sign a letter to insulin manufactures Eli Lilly and Company, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi over increased insulin prices and charging that the price increases caused patients to lack "access to the life-saving medications they need".[118]

In September 2019, amid discussions to prevent a government shutdown, Jones was one of six Democratic senators to sign a letter to congressional leadership advocating the passage of legislation to permanently fund health care and pension benefits for retired coal miners as "families in Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming, Alabama, Colorado, North Dakota and New Mexico" would start to receive notifications of health care termination by the end of the following month.[119]

In October 2019, Jones was one of 27 senators to sign a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer advocating the passage of the Community Health Investment, Modernization, and Excellence (CHIME) Act, which was set to expire the following month. The senators warned that if the funding for the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF) was allowed to expire, it "would cause an estimated 2,400 site closures, 47,000 lost jobs, and threaten the health care of approximately 9 million Americans."[120]

Immigration

[edit]In 2018, Jones participated in votes concerning immigration and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). He voted in favor of the McCain–Coons proposal to offer a pathway to citizenship to undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children, known as Dreamers, which did not include funding for a border wall; voted against withholding federal funding from sanctuary cities; voted for Susan Collins's bipartisan bill to offer a pathway to citizenship and federal funding for border security; and voted against Trump's proposal to offer a pathway to citizenship while reducing overall legal immigration numbers and using federal funds for a border wall.[121] He has also proposed reassessing the current quota system.[122] He has agreed that improvements in border security are needed but does not believe it is a national emergency.[123]

LGBT rights

[edit]Jones supports same-sex marriage and said that his son Carson, who is gay, helped change his views.[124] In 2017, he was endorsed by the Human Rights Campaign, which supports LGBT rights.[125] Jones supports protections for transgender students and transgender troops.[126]

United States Postal Service

[edit]In March 2019, Jones co-sponsored a bipartisan resolution led by Gary Peters and Jerry Moran that opposed privatization of the United States Postal Service (USPS), citing the USPS as a self-sustaining establishment and noting concerns that privatization could cause higher prices and reduced services for USPS customers, especially in rural communities.[127]

Taxes

[edit]Jones has not called for tax increases and has instead called for reductions in corporate taxes "to try to get reinvestment back into this country".[128] He opposed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, calling it fiscally irresponsible and skewed to benefit the wealthy while ignoring or hurting the middle class.[128]

In 2019, along with fellow Democrat Amy Klobuchar and Republicans Pat Toomey and Bill Cassidy, Jones was a lead sponsor of the Gold Star Family Tax Relief Act, a bill to undo a provision in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that raised the tax on the benefit children receive from a parent's Department of Defense survivor benefits plan to 37% from an average of 12% to 15%. The bill passed in the Senate in May 2019.[129]

Trade

[edit]In 2018, along with Joni Ernst and Rob Portman, Jones introduced the Trade Security Act, a bill that would modify Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to require that the Defense Department justify the national-security basis for new tariffs under Section 232 and implement an increase of congressional oversight of the process. Jones said the process currently led by the Commerce Department to investigate whether a trading partner is undermining U.S. national security had "been misused to target important job-creating industries in Alabama like auto manufacturing" and that the bill would refocus "efforts on punishing bad actors, rather than hurting American manufacturers, workers, and consumers."[130]

In December 2018, Jones stated that automakers and soybean farmers were fearful of the Trump administration's trade policy and added that his constituents in Alabama were questioning Trump's success.[131]

In February 2019, amid a report by the Commerce Department that ZTE had been caught illegally shipping goods of American origin to Iran and North Korea, Jones was one of seven senators to sponsor a bill reimposing sanctions on ZTE in the event that ZTE did not honor both American laws and its agreement with the Trump administration.[132]

In a July 2019 committee hearing, Jones predicted that tariffs would eventually directly hit the consumer and they would witness "tariffs that are going to cause a depletion in supply of things like Bibles and artificial fishing lures, which are fairly standard staples in Alabama."[133]

Addressing the North Alabama International Trade Association in September 2019, Jones said Alabama had a fairly robust economy that was also "pretty fragile and it could go completely bust if we don't get this trade war with China and other trade issues resolved and resolved soon", and that uncertainty about tariffs was affecting business confidence.[134]

Veterans

[edit]In December 2018, Jones was one of 21 senators to sign a letter to United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie calling it "appalling that the VA is not conducting oversight of its own outreach efforts" in spite of suicide prevention being the VA's highest clinical priority and requesting that Wilkie "consult with experts with proven track records of successful public and mental health outreach campaigns with a particular emphasis on how those individuals measure success".[135]

Personal life

[edit]

Jones married Louise New on December 12, 1992.[136] They have three children.[137] Jones' father died of dementia on December 28, 2019.[138]

Jones has been a member of the Canterbury United Methodist Church in Mountain Brook for more than 33 years.[139] He also serves on the advisory board of the Blackburn Institute, a leadership development and civic engagement program at the University of Alabama.[140]

Electoral history

[edit]

2017

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Doug Jones | 109,105 | 66.1 | |

| Democratic | Robert Kennedy Jr. | 29,215 | 17.7 | |

| Democratic | Michael Hansen | 11,105 | 6.7 | |

| Democratic | Will Boyd | 8,010 | 4.9 | |

| Democratic | Jason Fisher | 3,478 | 2.1 | |

| Democratic | Brian McGee | 1,450 | 0.9 | |

| Democratic | Charles Nana | 1,404 | 0.9 | |

| Democratic | Vann Caldwell | 1,239 | 0.8 | |

| Total votes | 165,006 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Doug Jones | 673,896 | 50.0% | |

| Republican | Roy Moore | 651,972 | 48.3% | |

| Write-in | 22,852 | 1.7% | ||

| Total votes | 1,348,720 | 100.0% | ||

| Democratic gain from Republican | ||||

2020

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Tommy Tuberville | 1,392,076 | 60.1% | ||

| Democratic | Doug Jones (incumbent) | 920,478 | 39.7% | ||

| Write-in | 3,891 | 0.2% | |||

| Total votes | 2,316,445 | 100% | |||

| Republican gain from Democratic | |||||

Book

[edit]- Jones, Doug. Bending Toward Justice: The Birmingham Church Bombing that Changed the Course of Civil Rights. New York: All Points Books, 2019.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "President Biden Announces Additional Advisors for Supreme Court Process". The White House. February 2, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ "Doug Jones (@DougJones46)". Twitter. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Jacobs, Ben; Smith, David (December 13, 2017). "Alabama election: Democrats triumph over Roy Moore in major blow to Trump". The Guardian. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Chandler, Kim; Peoples, Steve (December 13, 2017). "Democrat Jones wins stunning red-state Alabama Senate upset". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Beaman, Jeremy (April 13, 2018). "Sen. Doug Jones has proved himself — so far — to be a moderate Democrat". YellowHammer News. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Clare Foran (November 4, 2020). "Democrat Doug Jones loses Alabama Senate seat to Republican Tommy Tuberville". CNN.

- ^ Lonas, Lexi (January 29, 2021). "Doug Jones joining CNN as political commentator". The Hill. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Doug Jones". Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy, Institute of Politics and Public Service. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ "Meet Doug Jones": "Doug's parents, Gordon and Gloria Jones, live in Birmingham and his sister Terrie Savage and her husband Scott live in Hartselle". Doug Jones for Senate. August 16, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Gordon Jones Obituary (1931 - 2019) - The Birmingham News". obits.al.com.

- ^ Sack, Kevin (May 5, 2001), "PUBLIC LIVES; An Alabama Prosecutor Confronts the Burden of History", The New York Times, retrieved May 18, 2017

- ^ "Who is Doug Jones? Alabama Senate Race Heats up". Newsweek. December 10, 2017.

- ^ Cobb, Martin (Spring 2018). "Brother Senator". The Beta Theta Pi. p. 10. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Gray, Jeremy (May 11, 2017). "Doug Jones announces run for US Senate". The Birmingham News. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Murnaghan. "Douglas Jones" (PDF). Public Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ 1994 Election Results Archive - Alabama Legislature. Available at: https://www.sos.alabama.gov/alabama-votes/voter/election-data. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "President Clinton today announced his intent to nominate G. Douglas Jones to serve as United States Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama" (Press release). White House Office of the Press Secretary. August 18, 1997. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Panel Discussion: Criminal Discovery In Practice, 15 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 781, 782 n.2 (1999).

- ^ Verhoevek, John (September 27, 2017). "Meet the Alabama Senate candidates: Controversial gun-toting judge Roy Moore and a lawyer who fought the KKK". ABC News.

- ^ "Bombing Suspect Eric Rudolph Indicted". ABC News. November 15, 2000. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Gettlman, Jeffrey (June 3, 2003). "Bombing Suspect Is Moved to Alabama, for Trial There First". The New York Times.

- ^ Sack, Kevin (April 25, 2001). "As Church Bombing Trial Begins in Birmingham, the City's Past Is Very Much Present". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (September 14, 2013). "Prosecutor reflects on 50th anniversary of 1963 Birmingham bombing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Lamb, Yvonne (November 19, 2004). "Birmingham Bomber Bobby Frank Cherry Dies in Prison at 74". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Faulk, Kent (August 3, 2016). "16th Street Baptist Church bomber Thomas Blanton denied parole". The Birmingham News. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Thomas Blanton, 16th Street Baptist Church bomber, dies in prison". wbrc.com. June 26, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Sen. Doug Jones to release book in 2019". AL.com. April 10, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Birmingham attorneys Doug Jones and Greg Hawley form law firm". al. June 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Faulk, Kent (June 7, 2013). "Birmingham attorneys Doug Jones and Greg Hawley form law firm". AL.com. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Doug Jones: Justice Delayed, not Justice Denied". University of Kentucky Law School. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "About Doug Jones". Seeking Justice Today. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Federal prosecutor to speak at black history group's banquet". Texarkana Gazette. January 26, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Testimony of G. Douglas Jones" (PDF). U.S. House Judiciary Committee. June 12, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Testimony of G. Douglas Jones-"Allegations of Selective Prosecution: The Erosion of Public Confidence in our Federal Judicial System"" (PDF). Subcommittee on Commercial & Administration Law of the Committee on Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives. October 23, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ O'Donnell, Joe (October 1, 2015). "2015 Fusion Awards". B-Metro Magazine. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Scott, Ryan (June 27, 2017). "Democratic Senate candidate Doug Jones launches campaign headquarters in Birmingham". Weld Birmingham. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ "Doug Jones exploring run for U.S. Senate". Birmingham Post-Herald. August 15, 2001. p. 40. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Doug Jones faces long odds in Senate bid (cont.)". Birmingham Post-Herald. August 17, 2001. p. 4. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ Kizzire, Jaime (May 7, 2001). "Could verdict lead to office?". Birmingham Post-Herald. p. 23. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Doug Jones ends race for U.S. Senate". The Dothan Eagle. February 19, 2002. p. 9. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ Gray, Jeremy (May 10, 2017). "Doug Jones announces run for US Senate". The Birmingham News. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloch, Matthew; Lee, Jasmine (August 15, 2017). "Alabama Election Results: Two Republicans Advance, Democrat Wins in U.S. Senate Primaries". The New York Times. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Bloch, Matthew; Cohn, Nate; Katz, Josh; Lee, Jasmine (December 12, 2017). "Alabama Election Results: Doug Jones Defeats Roy Moore in U.S. Senate Race". The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Meet Doug Jones". Doug Jones for U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Kaitlan Collins (December 15, 2017). "Trump and Steve Bannon urge Roy Moore to concede". CNN.

- ^ Nelson, Louis (December 28, 2017). "Roy Moore loses lawsuit seeking new election". Politico. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Arkin, James (February 20, 2019). "GOP congressman jumps into critical Alabama Senate race". Politico. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "United States Senate election in Alabama, 2020 (March 3 Democratic primary)". Ballotpedia.

- ^ Mangan, Dan (November 4, 2020). "Tommy Tuberville projected to win Alabama Senate race over incumbent Sen. Doug Jones, a pickup for Republicans". CNBC.

- ^ "Alabama Election Results". The New York Times. November 3, 2020 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Alabama U.S. Senate Primary Election Results". The New York Times. October 28, 2020 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Weigel, David; Sullivan, Sean (January 3, 2018). "Doug Jones is sworn in, shrinking GOP Senate majority". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Latest: Moore not conceding Senate race to Jones". ABC News. Associated Press. December 13, 2017. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Terkel, Amanda; Campbell, Andy (December 12, 2017). "Alabama Elects Doug Jones, The State's First Democratic Senator In 25 Years". The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ "Doug Jones swearing-in: Watch live as Senate seats new Alabama member". AL.com. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Lee, Jasmine C. (2018). "How Every Senator Voted on the Government Shutdown". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Easley, Cameron (July 17, 2019). "Morning Consult's Senator Approval Rankings". Morning Consult. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Carney, Jordain. "Democrats block foreign policy bill over shutdown fight". The Hill.

- ^ Lyman, Brian (September 26, 2019). "Doug Jones calls for 'fact-finding' probe of allegations against Trump". Montgomery Advertiser.

- ^ Everett, Burgess (January 28, 2020). "Trio of Dem senators considering vote to acquit Trump". Politico. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Levine, Marianne; Arkin, James (February 5, 2020). "Red state Democrats stick with party to convict Trump". POLITICO. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Sen. Doug Jones appointed to 4 Senate committees". WALA-TV. January 9, 2018. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ "Who Are Contenders for Biden's Cabinet?". The New York Times. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Doug Jones named as politics fellow at Georgetown". January 20, 2021.

- ^ "Former U.S. Sen. Doug Jones joins D.C. law firm". al. May 3, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Katie (February 1, 2022). "White House Chooses Doug Jones to Guide Supreme Court Nominee". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Levine, Marianne; Everett, Burgess (April 5, 2022). "Jackson confirmation battle rejuvenates Doug Jones". POLITICO. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Baker, Sam (April 7, 2022). "Ketanji Brown Jackson confirmed as first Black female Supreme Court justice". Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Our view: Alabama voters must reject Roy Moore; we endorse Doug Jones for U.S. Senate". AL.com. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "Doug Jones, Roy Moore's opponent in Alabama, on verge of history in Senate election". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Pappas, Alex (November 18, 2017). "Alabama Democrat Doug Jones denies being an 'ultra-liberal,' says he opposes Trump's border wall". Fox News Channel. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Sharp, John (October 18, 2017). "Doug Jones talks 'kitchen table' issues and tax reform at Mobile rally". AL.com.

- ^ a b c Lyman, Brian (July 7, 2017). "Alabama Senate profile: Doug Jones wants to stress 'kitchen table issues'". Montgomery Advertiser.

- ^ Parks, Mary Alice (November 16, 2017). "Democrats weigh how to best help Alabama Senate candidate". ABC News. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Lyman, Brian (November 8, 2017). "Doug Jones, Roy Moore talk law enforcement in Montgomery stops". Montgomery Advertiser.

- ^ "Transcript: An interview with Doug Jones". The Economist. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ Yen, Hope (December 17, 2017). "Doug Jones says don't expect him to always side with Senate Democrats". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Thomsen, Jacqueline (November 13, 2017). "Flake: I'll support the Democrat over Moore in Alabama Senate race". The Hill. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Abramson, Alana (December 5, 2017). "GOP Senator Jeff Flake Just Wrote a Check to Roy Moore's Democratic Opponent". Time. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron (January 30, 2017). "Tracking Doug Jones In The Age Of Trump". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Edelman, Adam; Shabad, Rebecca (July 2, 2018). "Alabama Democrat Doug Jones walks tightrope with Trump and his own party". NBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Gore, Leada (January 31, 2018). "Senate rejects 20-week abortion ban; GOP criticizes Jones vote". AL.com. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Holter, Lauren (December 13, 2017). "Doug Jones Has Made His Stance On Abortion Crystal Clear". Bustle. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Berry, Deborah Barfield (May 16, 2019). "Alabama Democratic Sen. Doug Jones calls state's new restrictive abortion law 'shameful'". USA Today. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Parke, Caleb; Re, Gregg (February 25, 2019). "Dems block 'born alive' bill to provide medical care to infants who survive failed abortions". Fox News.

- ^ "Senator Doug Jones Champions Rural Alabama Priorities in Final Farm Bill Legislation". Jones.Senate.Gov. December 11, 2018. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Bechtel, Wyatt (May 1, 2019). "Senators Reintroduce Transporting Livestock Across America Safely Act". dailyherd.com.

- ^ Arlen, Gary (June 28, 2019). "Senators Propose $5 Billion Plan for Rural Broadband Buildout". multichannel.com.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas (December 18, 2018). "Senate Passes Bipartisan Criminal Justice Bill". The New York Times.

In one of this Congress's final acts, every Democrat and all but 12 Republicans voted in favor of the legislation — an outcome that looked highly unlikely this month amid skepticism from Republican leaders.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark (June 10, 2019). "U.S. senators launch bill to broaden shell companies' disclosures". kfgo.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Iannelli, Jerry (March 21, 2018). "Sen. Bill Nelson Votes to Continue Helping Saudi Arabia Kill Yemeni Citizens". Miami News Times.

- ^ Gattis, Paul (November 8, 2017). "Doug Jones: Strong national defense 'incredibly important'". AL.com.

- ^ "Doug Jones opposes Trump's CIA nominee". Alabama Daily News. May 16, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Ghosh, Nirmal (May 24, 2019). "US Bill reintroduced to deter China in South China, East China seas". The Straits Times.

- ^ Thornton, William (August 20, 2019). "Doug Jones decries using U.S.-Israel relations 'as political weapon'". AL.com.

- ^ Koplowitz, Howard (October 17, 2019). "Doug Jones joins bipartisan group of senators in urging Trump to rethink Syria policy". al.com.

- ^ Porter, Tom (September 27, 2017). "Who is Doug Jones, the KKK-fighting Democrat taking on far-right Roy Moore in the Alabama Senate race?". Newsweek. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ Gore, Leada (January 20, 2018). "Sen. Doug Jones votes for Republican-backed budget deal". AL.com. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Schoen, Jacob; Pramuk, John W. (March 15, 2018). "Why 17 Democrats voted with Republicans to ease bank rules". CNBC. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Hrynkiw, Ivana (July 24, 2018). "Sen. Doug Jones tweets back at Trump: Tariffs are the 'worst'". AL.com. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Varnier, Julia (February 13, 2019). "Warner, Thune introduce legislation to address student debt crisis". wtkr.com.

- ^ "Smith co-introduces bill to boost sagging teacher numbers across country". Brainerd Dispatch. July 31, 2019.

- ^ Douglas-Gabriel, Danielle (September 19, 2019). "Lamar Alexander blocks vote on funding for minority-serving colleges". SFGate.

- ^ Carney, Jordain; Green, Miranda (March 26, 2019). "Senate blocks Green New Deal". The Hill.

- ^ "Oregon senators call on Trump to honor climate agreement". ktvz.com. June 10, 2019. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ Connolly, Griffin (March 5, 2018). "Alabama Ready for More Gun Control, Sen. Doug Jones Says". Roll Call. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Sanchez, Luis (April 1, 2018). "Democrat: A gun ban is not 'feasible right now'". The Hill. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Koplowitz, Howard (March 21, 2018). "'It is time': Doug Jones calls on Senate to unite on stemming gun violence in floor speech". AL.com. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Carney, Jordain (March 26, 2018). "Senate Dems request health panel hearing on school shootings". The Hill.

- ^ Gaudiano, Nicole (March 5, 2018). "School safety bill introduced by bipartisan senators in response to Florida shooting". wfmynews2.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ "Collins-backed push to keep criminals from guns progresses". seacoastonline.com. March 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Gattis, Paul (November 6, 2017). "Doug Jones pledges to 'fix broken health care' in new Senate campaign ad". AL.com.

- ^ "Senate confirms Alex Azar as Trump's new health secretary". ABC News. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin Calls on Trump Administration to Stop Pushing Health Insurance Plans that Weaken Pre-Existing Condition Protections". urbanmilwaukee.com. December 20, 2018.

- ^ "Shaheen introduces bill that would delay health insurance tax". mychamplainvalley.com. January 21, 2019.

- ^ Holdren, Wendy (January 4, 2019). "Legislation introduced to secure miners pensions and health care". The Register-Herald.

- ^ "Democratic Senators "Alarmed" by Shutdown's Potential Impact on Food Safety". foodsafetymagazine.com. January 15, 2019.

- ^ "Sen. Kaine calls on pharmaceutical companies to explain skyrocketing insulin prices". WVEC. February 5, 2019.

- ^ "Manchin, colleagues send letter urging permanent funding for miners health care, pensions". wvmetronews.com. September 16, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin Working to Extend Long Term Funding for Community Health Centers". Urban Milwaukee. October 23, 2019.

- ^ Schoen, John W. (February 16, 2018). "How your senators voted on failed immigration proposals". CNBC. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ "Where Doug Jones Stands on Immigration Policy". Immigration Impact. December 13, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Gattis, Paul (January 19, 2019). "Sen. Doug Jones calls Trump proposal 'hopeful sign'". Al.com. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Sobel, Ariel (April 12, 2018). "Alabama Sen. Doug Jones Says Gay Son Led Him to Be More Pro-LGBT". Advocate. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Doug Jones' Ratings and Endorsements". Vote Smart.

- ^ Graef, Aileen; Kenny, Caroline. "Who is Doug Jones, who just won in Alabama?". CNN. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Peters, Moran reintroduce bipartisan resolution opposing privatization of USPS". uppermichiganssource.com. March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Kruzel, John (November 28, 2017). "Donald Trump wrongly claims Doug Jones wants to raise taxes". PolitiFact. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ "Klobuchar bill protecting Gold Star families from Trump tax hike passes Senate". Brainerd Dispatch. May 23, 2019.

- ^ Patton, Elizabeth (August 1, 2018). "Doug Jones introduces bipartisan bill to reform process for national security tariffs, increase oversight". Alabama Today.

- ^ Bowden, John (December 13, 2018). "Doug Jones: Carmakers 'scared to death' over Trump tariffs". The Hill.

- ^ "U.S. lawmakers target China's ZTE with sanctions bill". Reuters. February 5, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, James (July 17, 2019). "Top Trump advisor: China is on the 'wrong side of history' if they reject trade deal". fox17.com.

- ^ Dafnis, Jordan (September 5, 2019). "Sen. Doug Jones talks about China trade war with North Alabama business owners". whnt.com.

- ^ "U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin Presses VA for Answers on Misuse Of Suicide Prevention Funds". urbanmilwaukee.com. January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Meet Doug Jones": "Doug is married to the former Louise New from Cullman, Alabama. They will celebrate their 25th anniversary the night of the Special Election in December". Doug Jones for Senate. August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ Jones, Doug (August 16, 2017). "Meet Doug Jones". Doug Jones for Senate. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Father of Alabama Sen. Doug Jones dies after dementia fight". abc3340.com. The Associated Press. January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ Garrison, Greg (September 28, 2017). "Son of a steelworker, Doug Jones works to connect with Alabama voters". AL.com. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ "Advisory Board". Blackburn Institute. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ "2017 Official General Election Results without Write-In Appendix - 2017-12-28.pdf" (PDF). Alabama Secretary of State. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "Who got the most write-in votes in Alabama's Senate race? Nick Saban makes top 7". Al.com. December 20, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "State of Alabama - Canvass of Results -" (PDF). Alabama Secretary of State. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1954 births

- Living people

- People from Fairfield, Alabama

- Alabama lawyers

- 21st-century Alabama politicians

- American United Methodists

- Candidates in the 2017 United States elections

- Cumberland School of Law alumni

- Democratic Party United States senators from Alabama

- Biden administration personnel

- Samford University alumni

- United States Attorneys for the Northern District of Alabama

- University of Alabama alumni

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 21st-century American lawyers

- 20th-century Methodists

- 21st-century Methodists

- 21st-century United States senators