Development of Doom

Doom, a first-person shooter game by id Software, was released in December 1993 and is considered one of the most significant and influential video games in history.[1][2][3] Development began in November 1992, with programmers John Carmack and John Romero, artists Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud, and designer Tom Hall. Late in development, Hall was replaced by Sandy Petersen and programmer Dave Taylor joined. The music and sound effects were created by Bobby Prince.

The Doom concept was proposed in late 1992, after the release of Wolfenstein 3D and its sequel Spear of Destiny. John Carmack was working on an improved 3D game engine from those games, and the team wanted to have their next game take advantage of his designs. Several ideas were proposed, including a new game in their Commander Keen series, but John proposed a game about using technology to fight demons inspired by the Dungeons & Dragons campaigns the team played. The initial months of development were spent building prototypes, while Hall created the Doom Bible, a design document for his vision of the game and its story; after id released a grandiose press release touting features that the team had not yet begun working on, the Doom Bible was rejected in favor of a plotless game with no design document at all.

Over the next six months, Hall designed levels based on real military bases, Romero built features, and artists Adrian Carmack and Cloud created textures and demons based on clay models they built. Hall's level designs, however, were deemed uninteresting and Romero began designing his own levels; Hall, increasingly frustrated with his limited influence, was fired in July. He was replaced by Petersen in September, and the team worked increasingly long hours until the game was completed in December 1993. Doom was self-published by id on December 10, 1993, and immediately downloaded by thousands of players.

Design

[edit]

Concept

[edit]In May 1992, id Software released Wolfenstein 3D. It is often referred to as the "grandfather" of first-person shooters,[4][5] setting expectations for fast-paced action and new technology, and greatly increased the genre's popularity.[4][6][7][8] Immediately following its release, most of the team began work on a set of new Wolfenstein episodes, Spear of Destiny. As the episodes used the same game engine as the original game, id co-founder and lead programmer John Carmack instead focused on technology research for the company's next game, just as he had experimented with creating a 3D game engine prior to the development of Wolfenstein 3D. Between May and Spear of Destiny's release in September 1992, he created several experimental engines, including one for a racing game, before working on an enhanced version of the Wolfenstein engine to be licensed to Raven Software for their game ShadowCaster. For this engine, he developed several enhancements to the Wolfenstein engine, including sloped floors, textures on the floors and ceilings in addition to the walls, and fading visibility over a distance. The resulting engine was much slower than the Wolfenstein one, but was deemed acceptable for an adventure game like ShadowCaster.[9]

Following the release of Spear of Destiny and the completion of the ShadowCaster engine, id Software discussed what their next game would be. They wanted to create another 3D game using Carmack's new engine as a starting point, but were largely tired of Wolfenstein. Lead designer Tom Hall was especially weary of it, and pushed for the team to make another game in the Commander Keen series; the team had created seven episodes in the series in 1990–91 as their first games, but the planned third set of episodes had been dropped in favor of Wolfenstein 3D. While Carmack was initially interested in the idea, the rest of the team was not. They collectively felt that the platforming gameplay of the series was a poor fit for Carmack's fast-paced 3D engines, and especially after the success of Wolfenstein were interested in pursuing more games of that type. Additionally, the other two co-founders of id were not interested in creating another Keen game: John Romero, the designer of Wolfenstein, was not interested in doing another "cutesy" game, and lead artist Adrian Carmack preferred to create art in a darker style than the Keen games. John Carmack soon lost interest in Keen idea as well, instead coming up with his own concept: a game about using technology to fight demons, inspired by the Dungeons & Dragons campaigns the team played, combining the styles of Evil Dead II and Aliens.[9][10] The concept originally had a working title of "Green and Pissed", which was also the name of a concept Hall had proposed prior to Wolfenstein, but Carmack soon named the proposed game after a line in the film The Color of Money: "'What's in the case?' / 'In here? Doom.'"[9][11]

The team agreed to pursue the Doom concept, and development began in November 1992.[10] The initial development team was composed of five people: programmers John Carmack and John Romero, artists Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud, and designer Tom Hall.[12] They moved offices to a dark office building, which they named "Suite 666", and drew inspiration from the noises coming from the dentist's office next door. They also cut ties with Apogee Software, who had given them the initial advance money for creating their first game, Commander Keen in Invasion of the Vorticons, and through which they had published the shareware versions of their games to date. While they had a good personal relationship with owner Scott Miller, they felt that they were outgrowing the publisher. Cloud, who was involved in id's business dealings, pushed for id to take over shareware publishing duties themselves after investigating and finding that Apogee was unable to reliably handle the volume of customers buying id's games through Apogee. He convinced the others that the increased sales revenue would make up for the problems of handling their own publishing. The two companies parted amicably, and Doom was set to be self-published.[13]

Development

[edit]

Early in development, rifts in the team began to appear. Hall, who despite having wanted to develop a different game remained the lead designer and creative director for the company, did not want Doom to have the same lack of plot as Wolfenstein 3D. At the end of November he delivered a design document, which he named the Doom Bible, that described the plot, backstory, and design goals for the project.[10] His design was a science fiction horror concept wherein scientists on the Moon open a portal from which aliens emerge. Over a series of levels the player discovers that the aliens are demons; Hell also steadily infects the level design as the atmosphere becomes darker and more terrifying.[14] While Romero initially liked the idea, John Carmack not only disliked it but dismissed the idea of having a story at all: "Story in a game is like story in a porn movie; it's expected to be there, but it's not that important." Rather than a deep story, John Carmack wanted to focus on the technological innovations, dropping the levels and episodes of Wolfenstein in favor of a fast, continuous world. Hall disliked the idea, but Romero sided with Carmack. Although John Carmack was the lead programmer rather than a designer, he was becoming seen in the company as the most important source of ideas; the company considered taking out key person insurance on Carmack but no one else.[14]

Hall spent the next few weeks reworking the Doom Bible to work with Carmack's technological ideas, while the rest of the team planned how they could implement them.[10] His adjusted vision for the plot had the player character assigned to a large military base on an alien planet, Tei Tenga. At the start of the game, as the first of four player character soldiers, named Buddy, played cards with the others, scientists on the base accidentally open a portal to Hell, through which demons poured through, killing the other soldiers. He envisioned a six episode structure with a storyline involving traveling to Hell and back through the gates which the demons used, and the destruction of the planet, for which the players would be sent to jail.[14][15] Buddy was named after Hall's character in a Dungeons & Dragons campaign run by John Carmack that had featured a demonic invasion.[14] Hall was forced to rework the Doom Bible again in December, however, after John Carmack and the rest of the team had decided that they were unable to create a single, seamless world with the hardware limitations of the time, which contradicted much of the new document.[10]

At the start of 1993, id put out a press release by Hall, touting Buddy's story about fighting off demons while "knee-deep in the dead", trying to eliminate the demons and find out what caused them to appear. The press release proclaimed the new game features that John Carmack had created, as well as other features, including multiplayer gaming features, that had not yet been started on by the team or even designed.[14] The company told Computer Gaming World that Doom would be "Wolfenstein times a million!"[16] Early versions were built to match the Doom Bible; a "pre-alpha" version of the first level included the other characters at a table and movable rolling chairs based on ones at the id office.[17] Initial versions also retained "arcade" elements present in Wolfenstein 3D, like score points and score items, but those were removed early in development as they felt unrealistic and not in keeping with the tone.[12] Other elements, such as a complex user interface, an inventory system, a secondary shield protection, and lives were modified and slowly removed over the course of development.[10][18]

Soon, however, the Doom Bible as a whole was rejected: Romero wanted a game even "more brutal and fast" than Wolfenstein, which did not leave room for the character-driven plot Hall had created.[14] Additionally, the team did not feel that they needed a design document at all, as they had not created one for prior games; the Doom Bible was discarded altogether.[14] Several ideas were retained, including starting off in a military base, as well as some locations, items, and monsters, but the story was dropped and most of the design was removed as the team felt it emphasized realism over entertaining gameplay. Some elements, such as weapons, a hub system of maps, and monorails later appeared in later Doom or id games.[15] Work continued, and a demo was shown to Computer Gaming World in early 1993, who raved about it. John Carmack and Romero, however, disliked Hall's military base-inspired level design. Romero especially felt that while John Carmack had originally asked for realistic levels as they would make the engine run quickly, that Hall's level designs were uninspiring.[14] He felt that the boxy, flat levels were too similar to Wolfenstein's design, and did not show off everything the engine could do.[19] He began to create his own, more abstract levels, beginning with a curving staircase into a large open area in what became the second level of the final game, which the rest of the team felt was much better.[14][19]

Hall was upset with the reception to his designs and how little impact he was having as the lead designer; Romero has since claimed that Hall was also still uninterested in the Doom concept at all.[14][17] Hall was also upset with how much he was having to fight with John Carmack in order to get what he saw as obvious gameplay improvements, such as flying enemies.[10] The other developers, however, felt that Hall was not in sync with the team's vision for the game and was becoming a problem.[20] He began to spend less time working in the office, and in response John Carmack proposed that he be fired from id. Romero initially resisted, as it would mean that Hall would not receive any proceeds, but in July he and the other founders of id fired Hall, who went to work for Apogee.[14] Hall was replaced in September, ten weeks before Doom was released, by game designer Sandy Petersen, despite misgivings over his relatively high age of 37 compared to the other early-20s employees and his religious background.[21][22] Petersen later recalled that John Carmack and Romero wanted to hire other artists instead, but Cloud and Adrian disagreed, saying that a designer was required to help build a cohesive gameplay experience. They relented and Petersen was hired.[23] The team also added a third programmer, Dave Taylor.[24] Romero directed Petersen to revise Hall's levels with as many changes as he saw fit in order to meet his guidelines for what made for interesting levels.[20] Petersen and Romero designed the rest of the levels for Doom, with different aims: the team felt that Petersen's designs were more technically interesting and varied, while Romero's were more aesthetically interesting.[22] Romero's level design process was to build a level or part of a level, starting at the beginning, then play through it and iterate on the design, so that by the time he was satisfied with the flow and playability of the level he had played it "a thousand times". The first level, made by Romero, was the last created, intended to show off the new elements of the engine.[12] The ending screen of each level, like in Wolfenstein 3D, displays a "par time" for the level, as set by Romero.[17]

In late 1993, a month before release, John Carmack began to add multiplayer to the game, first teaching himself computer networking from a book.[20] After the multiplayer component was coded, the development team began playing four-player multiplayer games matches, which Romero termed "deathmatch"; he proposed adding a cooperative multiplayer mode as well.[25] Cloud named the act of killing other players "fragging".[20] According to Romero, the deathmatch mode was inspired by fighting games. The team frequently played Street Fighter II, Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting during breaks, while developing elaborate rules involving trash-talk and smashing furniture or equipment. Romero later stated that "you could say that Japanese fighting games fueled the creative impulse to create deathmatch in our shooters".[26]

Programming

[edit]

Doom was programmed largely in the ANSI C language, with a few elements in assembly language, on NeXT computers running the NeXTSTEP operating system.[27] The data, including level designs and graphics files, is stored in WAD files, short for "Where's All the Data?". This allows for any part of the design to be changed without needing to adjust the engine code. Carmack had been impressed by the modifications made by fans of Wolfenstein 3D, and wanted to support that with an easily swappable file structure, and released the map editor online.[28]

Romero and Carmack spent the early stage of development focusing on engine features instead of the game concept. Wolfenstein had required levels to be a flat plane, with walls at the same height and at right angles; while the Doom world was still a variation on a flat plane, in that two traversable areas could not be on top of each other, it could have walls and floors at any angle or height, allowing greater level design variety. The fading visibility in ShadowCaster was improved by adjusting the color palette by distance, darkening far surfaces and creating a grimmer, more realistic appearance.[14] This concept was also used for the lighting system: rather than calculating how light traveled from light sources to surfaces using ray tracing, the engine calculates the "light level" of a section of a level, which can be as small as a single stair step, based on its distance from light sources. It then darkens the color palette of that section's surface textures accordingly.[27] Romero used the map editing tool he developed to build grandiose areas with these new possibilities, and came up with new ways to use Carmack's lighting engine such as strobe lights.[14] He also programmed engine features such as switches and movable stairs and platforms.[10][12]

In the first half of 1993, Carmack worked on improving the graphics engine. After Romero's level designs started to cause engine problems, he researched and began to use binary space partitioning to quickly select the portion of a level that the player could see at any given time.[10][22] In March 1993, the team stopped work on Doom to spend three weeks building a Super Nintendo Entertainment System port of Wolfenstein 3D, after the contractor hired for the port had made no progress.[10][24] Taylor, along with programming other features, added cheat codes; some, such as "idspispopd", were based on ideas their fans had come up with while eagerly awaiting the game that the team found amusing.[12] By late 1993, Doom was nearing completion and player anticipation was high, spurred on by a leaked press demo. John Carmack began to work on the multiplayer component; within two weeks he had two computers playing the same game over the internal office network.[25]

Graphics and sound

[edit]

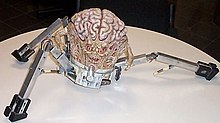

Adrian Carmack was the lead artist for Doom, with Kevin Cloud as an additional artist. Additionally, Don Ivan Punchatz was hired to create the package art and logo, and his son Gregor Punchatz created some of the monsters. Doom was the style of game that Adrian Carmack had wanted to create since id was founded, one with a dark style and demons. He and Cloud designed the monsters to be "nightmarish", and developed a new technique for animating them. The intent was to have graphics that were realistic and dark as opposed to staged or rendered, so a mixed media approach was taken to the artwork.[29] Unlike Wolfenstein, where Carmack had drawn every frame of animation for the Nazi enemy sprites, for Doom the artists sculpted models of some of the enemies out of clay, and took pictures of them in stop motion from five to eight different angles so that they could be rotated realistically in-game; the images were then digitized and converted to 2D characters with a program written by John Carmack.[14][30] Adrian Carmack made clay models for the player character, the Cyberdemon and the Baron of Hell, before deciding that the problems of keeping the clay consistent under lighting while moving the models through animations was too great.[10] Later, he had practical effects specialist Gregor Punchatz build a latex and metal sculpture of the Spider Mastermind.[12] Punchatz got the materials from hardware and hobby stores and used what he called "rubber band and chewing gum effects".[31] The weapons were toys, with parts combined from different toys to make more guns.[10] They scanned themselves as well, using Cloud's arm as the model for the player character's arm holding a gun, and Adrian's snakeskin boots and wounded knee for in-game textures.[14] Romero was the body model used for cover; while trying to work with a male model to get a reference photograph for Don Ivan Punchatz to work from, Romero became frustrated while trying to convey to him how to pose as if "the Marine was going to be attacked by an infinite amount of demons". Romero posed shirtless as a demonstration of the look he was trying for, and that photograph was the one used by Punchatz.[32] Electronic Arts's Deluxe Paint II was used in the creation of the sprites.[33]

Like they had for Wolfenstein 3D, id hired Bobby Prince to create the music and sound effects. Romero directed Prince to make the music in techno and metal styles; many of the songs were directly inspired by songs from popular metal bands such as Alice in Chains and Pantera.[22][34] Prince felt that more ambient music would work better, especially given the hardware limitations of the time on what sounds he could produce, and produced numerous tracks in both styles in the hopes of convincing Romero; Romero, however, still liked the metal tracks and added both styles.[35] Prince did not make music for specific levels; most of the music was composed before the levels they were eventually assigned to were completed. Instead, Romero assigned each track to each level late in development. Unlike the music, the sound effects for the enemies and weapons were created by Prince for specific purposes; Prince designed them based on short descriptions or concept art of a monster or weapon, and then adjusted the sound effects to match the completed animations.[36] The sound effects for the monsters were created from animal noises, and Prince designed all the sound effects to be distinct on the limited sound hardware of the time, even when many sound effects were playing at once.[22][35]

Release

[edit]Id Software planned to self-publish the game for DOS-based computers and set up a distribution system leading up to the release. Jay Wilbur, who had been brought on as CEO and sole member of the business team, planned the marketing and distribution of Doom. He felt that the mainstream press was uninterested, and as id would make the most money off of copies they sold directly to customers—up to 85 percent of the planned US$40 price—he decided to leverage the shareware market as much as possible, buying only a single ad in any gaming magazine. Instead, he reached out directly to software retailers, offering them copies of the first Doom episode for free, allowing them to charge any price for it, in order to spur customer interest in buying the full game directly from id.[22]

Doom's original release date was the third quarter of 1993, which the team did not meet. By December 1993, the team was working non-stop, with several employees sleeping at the office; programmer Dave Taylor claimed that the work gave him such a rush that he would pass out from the intensity. [25] Id only gave a single press preview, to Computer Gaming World in June, to a glowing response, but had also released development updates to the public continuously throughout development on the nascent internet. Id began receiving calls from people interested in the game or angry that it had missed its planned release date, as anticipation built over the year. At midnight on Friday, December 10, 1993, after working for 30 straight hours testing the game, the team uploaded the first episode to the internet, letting interested players distribute it for them.[20] So many users were connected to the first network that they planned to upload the game to—the University of Wisconsin–Parkside FTP network—that even after the network administrator increased the number of connections while on the phone with Wilbur, id was unable to connect, forcing them to kick all other users off to allow id to upload the game. When the upload finished thirty minutes later, 10,000 people attempted to download it at once, crashing the university's network. Within hours, other university networks were banning Doom multiplayer games, as a rush of players overwhelmed their systems.[25]

Development release versions

[edit]While Doom was in development, five pre-release versions were given names or numbers and shown to testers or the press.[10]

| Version | Release date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0.2 Alpha | February 4, 1993 | An early version two months into development; features texture mapping, variable light levels, and non-orthogonal walls in a single flat level. Has non-moving enemies, and a heads-up display (HUD) with elements from the Doom Bible, later removed. |

| 0.3 Alpha | February 28, 1993 | Another early version with changes to the interface. |

| 0.4 Alpha | April 2, 1993 | Contains nine levels, with some recognizable structures from the final game. The player has a rifle weapon which can be fired, though enemies still do not move. |

| 0.5 Alpha | May 22, 1993 | Contains fourteen levels, though the final level is not accessible; the sixth level was later used in Doom II instead of Doom. Items and environmental hazards are present and functional. The enemies do not attack, and disappear when shot. |

| Press release | October 4, 1993 | Similar to the release version, with some differences in weapons and level design. Three levels are included, which would become E1M2, E3M5 and E2M2 in the release version. |

References

[edit]- ^ Shoemaker, Brad (2006-02-02). "The Greatest Games of All Time: Doom". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ Lindsey, Patrick (2013-12-10). "20 Years of Doom: The Most Influential Shooter Ever". Paste. Wolfgang's. Archived from the original on 2017-06-11. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (2013-12-10). "'Doom' at 20: John Carmack's hellspawn changed gaming forever". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ a b Computer Gaming World. "CGW's Hall of Fame". 1UP.com. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 2016-07-27. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ Slaven, p. 53

- ^ Williamson, Colin. "Wolfenstein 3D DOS Review". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 2014-11-15. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games (2003)". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 2016-04-19. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ Shachtman, Noah (2008-05-08). "May 5, 1992: Wolfenstein 3-D Shoots the First-Person Shooter Into Stardom". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ^ a b c Kushner, pp. 118–121

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Romero, John; Hall, Tom (2011). Classic Game Postmortem – Doom (Video). Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on 2017-08-06. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ Antoniades, Alexander (2013-08-22). "Monsters from the Id: The Making of Doom". Gamasutra. UBM. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ^ a b c d e f "We Play Doom with John Romero". IGN. Ziff Davis. 2013-12-10. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ Kushner, pp. 122–123

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kushner, pp. 124–131

- ^ a b Mendoza, pp. 249–250

- ^ Walker, Bryan A. (January 1993). "Call of the Wild". Computer Gaming World. No. 102. pp. 100–102. ISSN 0744-6667.

- ^ a b c Batchelor, James (2015-01-26). "Video: John Romero reveals level design secrets while playing Doom". MCV. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on 2018-02-02. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ "On the Horizon". Game Players PC Entertainment. Vol. 6, no. 3. GP Publications. May 1993. p. 8.

- ^ a b Romero, John; Barton, Matt (2010-03-13). Matt Chat 53: Doom with John Romero (Video). Matt Barton. Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ a b c d e Romero, ch. 12: Destined to DOOM

- ^ Bub, Andrew S. (2002-07-10). "Sandy Petersen Speaks". GameSpy. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 2005-03-22. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f Kushner, pp. 132–147

- ^ Petersen, Sandy (April 20, 2020). Tales from the Dark Days of Id Software (Video). Retrieved March 15, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Romero, John (2016). The Early Days of id Software (Video). Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ a b c d Kushner, pp. 148–153

- ^ Consalvo, pp. 201–203

- ^ a b Schuytema, Paul C. (August 1994). "The Lighter Side of Doom". Computer Gaming World. No. 121. pp. 140–142. ISSN 0744-6667.

- ^ Kushner, p. 166

- ^ Mendoza, p. 247

- ^ Shahrani, Sam (2006-04-25). "Educational Feature: A History and Analysis of Level Design in 3D Computer Games - Pt. 1". Gamasutra. UBM. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

- ^ Kerr, Chris (2016-04-13). "Rubber bands and chewing gum: How practical effects shaped Doom". Gamasutra. UBM. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (2017-07-19). "John Romero finally reveals who the original Doom Guy really is". PC Gamer. Future. Archived from the original on 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ "John Carmack on Twitter: "Deluxe Paint II was the pixel tool for all the early Id Software games."". Twitter. 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- ^ Romero, John (2005-04-19). "Influences on Doom Music". rome.ro. Archived from the original on 2013-09-01. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ a b Pinchbeck, pp. 52–55

- ^ Prince, Bobby (2010-12-29). "Deciding Where To Place Music/Sound Effects In A Game". Bobby Prince Music. Archived from the original on 2011-08-12. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

Sources

[edit]- Consalvo, Mia (2016). Atari to Zelda: Japan's Videogames in Global Contexts. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03439-5.

- Pinchbeck, Dan (2013). Doom: Scarydarkfast. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05191-5.

- Kushner, David (2004). Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7215-3.

- Mendoza, Jonathan (1994). The Official DOOM Survivor's Strategies and Secrets. Sybex. ISBN 978-0-7821-1546-8.

- Romero, John (2023). Doom Guy: Life in First Person. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-5811-9.

- Slaven, Andy (2002). Video Game Bible, 1985-2002. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55369-731-2.