Famotidine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /fəˈmɒtɪdiːn/ |

| Trade names | Pepcid, Zantac 360, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a687011 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Histamine H2 receptor antagonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40–45% (by mouth)[2] |

| Protein binding | 15–20%[2] |

| Onset of action | 90 minutes |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5–3.5 hours[2] |

| Duration of action | 9 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (25–30% unchanged [Oral])[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.116.793 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

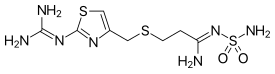

| Formula | C8H15N7O2S3 |

| Molar mass | 337.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Famotidine, sold under the brand name Pepcid among others, is a histamine H2 receptor antagonist medication that decreases stomach acid production.[4] It is used to treat peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.[4] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[4] It begins working within an hour.[4]

Common side effects include headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, and dizziness.[4] Serious side effects may include pneumonia and seizures.[4][5] Use in pregnancy appears safe but has not been well studied, while use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[1]

Famotidine was patented in 1979 and came into medical use in 1985.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[5] In 2022, it was the 49th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 13 million prescriptions.[7][8]

Medical uses

[edit]- Heartburn, acid indigestion, and sour stomach

- Treatment for gastric and duodenal ulcers

- Treatment for pathologic gastrointestinal hypersecretory conditions such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine adenomas

- Treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Treatment for esophagitis

- Part of a multidrug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication, although omeprazole may be somewhat more effective.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

- Prevention of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers.[15][16]

- Given to surgery patients before operations to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia.[17][18][19]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Famotidine has a delayed onset of action, beginning after 90 minutes. However, famotidine has a duration of effect of at least 540 minutes (9.0 h). At its peak effect, 210 minutes (3.5 h) after administration, famotidine reduces acid secretion by 7.3 mmol per 30 minutes.[20]

Side effects

[edit]The most common side effects associated with famotidine use include headache, dizziness, and constipation or diarrhea.[21][22]

Famotidine may contribute to QT prolongation,[23] particularly when used with other QT-elongating drugs, or in people with poor kidney function.[24]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Activation of H2 receptors located on parietal cells stimulates proton pumps to secrete acid into the stomach lumen. Famotidine, an H2 antagonist, blocks the action of histamine on the parietal cells, ultimately reducing acid secretion into the stomach.

Interactions

[edit]Unlike cimetidine, the first H2 antagonist, famotidine has a minimal effect on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system and does not appear to interact with as many drugs as other medications in its class. Some exceptions include antiretrovirals such as atazanavir, chemotherapeutics such as doxorubicin, and antifungal medications such as itraconazole. [25][26][27]

History

[edit]Famotidine was developed by Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co.[28] It was licensed in the mid-1980s by Merck & Co.[29] and is marketed by a joint venture between Merck and Johnson & Johnson. The imidazole ring of cimetidine was replaced with a 2-guanidinothiazole ring. Famotidine proved to be nine times more potent than ranitidine, and thirty-two times more potent than cimetidine.[30]

It was first marketed in 1981. Pepcid RPD orally disintegrating tablets were released in 1999. Generic preparations became available in 2001, e.g. Fluxid (Schwarz) or Quamatel (Gedeon Richter Ltd.).

In the United States and Canada, a product called Pepcid Complete, which combines famotidine with an antacid in a chewable tablet to relieve the symptoms of excess stomach acid quickly, is available. In the UK, this product was known as PepcidTwo until its discontinuation in April 2015.[31]

Famotidine has poor bioavailibility (50%) due to its low solubility in the high pH of the intestines. Researchers are developing formulations that use gastroretentive drug delivery systems such as floating tablets to increase bioavailability by promoting local delivery (directly into the stomach wall) of these drugs to receptors in the parietal cell membrane.[32]

Society and culture

[edit]Certain preparations of famotidine are available over-the-counter (OTC) in various countries. In the United States and Canada, 10 mg and 20 mg tablets, sometimes in combination with an antacid,[33][34] are available OTC. Larger doses still require a prescription.

Formulations of famotidine in combination with ibuprofen were marketed by Horizon Pharma under the trade name Duexis.[35]

Research

[edit]COVID-19

[edit]At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, some doctors observed that anecdotally some hospitalized patients in China may have had better outcomes on famotidine than other patients who were not taking famotidine. This led to hypotheses about use of famotidine in treatment of COVID-19.[36][37] Famotidine was considered a possible treatment for COVID-19 due to its potential anti-inflammatory effects. It was thought that famotidine could modify lung inflammation caused by coronaviruses. However, studies have shown that famotidine is not effective in reducing mortality or improving recovery in COVID-19 patients.[38] Famotidine primarily works by blocking the effects of histamine and has some potential mechanisms of action that may contribute to its anti-inflammatory properties, including the inhibition of the production of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6.[39][40] Another hypothesis was that famotidine might activate the vagus nerve inflammatory reflex to attenuate cytokine storm.[40] Yet another hypothesis was that famotidine can reduce the activation of mast cells and the subsequent release of inflammatory mediators, therefore acting as a mast cell stabilizer.[41][39] However, while famotidine may have some anti-inflammatory effects, there is currently insufficient evidence to support its use for treating inflammation associated with COVID-19.[38] Therefore, it is not recommended for this purpose.[42]

Other

[edit]Small-scale studies have shown inconsistent and inconclusive evidence of efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.[43]

Veterinary uses

[edit]Famotidine is given to dogs and cats with acid reflux.[44]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Famotidine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Famotidine tablet". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Zantac 360- famotidine tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Famotidine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 444. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Famotidine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Kanayama S (January 1999). "[Proton-pump inhibitors versus H2-receptor antagonists in triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 57 (1): 153–6. PMID 10036954.

- ^ Soga T, Matsuura M, Kodama Y, Fujita T, Sekimoto I, Nishimura K, et al. (August 1999). "Is a proton pump inhibitor necessary for the treatment of lower-grade reflux esophagitis?". Journal of Gastroenterology. 34 (4): 435–40. doi:10.1007/s005350050292. PMID 10452673. S2CID 22115962.

- ^ Borody TJ, Andrews P, Fracchia G, Brandl S, Shortis NP, Bae H (October 1995). "Omeprazole enhances efficacy of triple therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori". Gut. 37 (4): 477–81. doi:10.1136/gut.37.4.477. PMC 1382896. PMID 7489931.

- ^ Hu FL, Jia JC, Li YL, Yang GB (2003). "Comparison of H2-receptor antagonist- and proton-pump inhibitor-based triple regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients with gastritis or peptic ulcer". The Journal of International Medical Research. 31 (6): 469–74. doi:10.1177/147323000303100601. PMID 14708410. S2CID 25818901.

- ^ Kirika NV, Bodrug NI, Butorov IV, Butorov SI (2004). "[Efficacy of different schemes of anti-helicobacter therapy in duodenal ulcer]". Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 76 (2): 18–22. PMID 15106408.

- ^ Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Nebiki H, Chono S, Uno H, Kitada K, et al. (June 2005). "Famotidine vs. omeprazole: a prospective randomized multicentre trial to determine efficacy in non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 21 (Suppl 2): 10–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02468.x. PMID 15943841. S2CID 24690061.

- ^ La Corte R, Caselli M, Castellino G, Bajocchi G, Trotta F (June 1999). "Prophylaxis and treatment of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal disorders". Drug Safety. 20 (6): 527–43. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920060-00006. PMID 10392669. S2CID 41990751.

- ^ Laine L, Kivitz AJ, Bello AE, Grahn AY, Schiff MH, Taha AS (March 2012). "Double-blind randomized trials of single-tablet ibuprofen/high-dose famotidine vs. ibuprofen alone for reduction of gastric and duodenal ulcers". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 107 (3): 379–86. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.443. PMC 3321505. PMID 22186979.

- ^ Escolano F, Castaño J, López R, Bisbe E, Alcón A (October 1992). "Effects of omeprazole, ranitidine, famotidine and placebo on gastric secretion in patients undergoing elective surgery". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 69 (4): 404–6. doi:10.1093/bja/69.4.404. PMID 1419452.

- ^ Vila P, Vallès J, Canet J, Melero A, Vidal F (November 1991). "Acid aspiration prophylaxis in morbidly obese patients: famotidine vs. ranitidine". Anaesthesia. 46 (11): 967–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09860.x. PMID 1750602.

- ^ Jahr JS, Burckart G, Smith SS, Shapiro J, Cook DR (July 1991). "Effects of famotidine on gastric pH and residual volume in pediatric surgery". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 35 (5): 457–60. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03328.x. PMID 1887750. S2CID 44356956.

- ^ Feldman M (May 1996). "Comparison of the effects of over-the-counter famotidine and calcium carbonate antacid on postprandial gastric acid. A randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 275 (18): 1428–1431. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03530420056036. PMID 8618369.

- ^ "Common Side Effects of Pepcid (Famotidine) Drug Center". RxList. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Drugs & Medications". www.webmd.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Fazio G, Vernuccio F, Grutta G, Re GL (26 April 2013). "Drugs to be avoided in patients with long QT syndrome: Focus on the anaesthesiological management". World Journal of Cardiology. 5 (4): 87–93. doi:10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.87. PMC 3653016. PMID 23675554.

- ^ Lee KW, Kayser SR, Hongo RH, Tseng ZH, Scheinman MM (May 2004). "Famotidine and long QT syndrome". The American Journal of Cardiology. 93 (10): 1325–1327. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.025. PMID 15135720.

- ^ Wang X, Boffito M, Zhang J, Chung E, Zhu L, Wu Y, et al. (September 2011). "Effects of the H2-receptor antagonist famotidine on the pharmacokinetics of atazanavir-ritonavir with or without tenofovir in HIV-infected patients". AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 25 (9): 509–515. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.0113. PMC 3157302. PMID 21770762.

- ^ Hegazy SK, El-Haggar SM, Alhassanin SA, El-Berri EI (January 2021). "Comparative randomized trial evaluating the effect of proton pump inhibitor versus histamine 2 receptor antagonist as an adjuvant therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Medical Oncology. 38 (1): 4. doi:10.1007/s12032-020-01452-z. PMID 33394214. S2CID 230485193.

- ^ Lim SG, Sawyerr AM, Hudson M, Sercombe J, Pounder RE (June 1993). "Short report: the absorption of fluconazole and itraconazole under conditions of low intragastric acidity". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 7 (3): 317–321. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00103.x. PMID 8117350. S2CID 20462864.

- ^ US patent 4283408, Yasufumi Hirata, Isao Yanagisawa, Yoshio Ishii, Shinichi Tsukamoto, Noriki Ito, Yasuo Isomura and Masaaki Takeda, "Guanidinothiazole compounds, process for preparation and gastric inhibiting compositions containing them", issued 11 August 1981

- ^ "Sankyo Pharma". Skyscape Mediwire. 2002. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ Howard JM, Chremos AN, Collen MJ, McArthur KE, Cherner JA, Maton PN, et al. (April 1985). "Famotidine, a new, potent, long-acting histamine H2-receptor antagonist: comparison with cimetidine and ranitidine in the treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome". Gastroenterology. 88 (4): 1026–33. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80024-x. PMID 2857672.

- ^ "PepcidTwo Chewable Tablet". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Formulation and Evaluation of Gastroretentive Floating Tablets of Famotidine". Farmavita.Net. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Pepcid Complete

- ^ "Famotidine". Medline Plus. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Duexis". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Borrell B (April 2020). "New York clinical trial quietly tests heartburn remedy against coronavirus". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc4739. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Malone RW, Tisdall P, Fremont-Smith P, Liu Y, Huang XP, White KM, et al. (2021). "COVID-19: Famotidine, Histamine, Mast Cells, and Mechanisms". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12: 633680. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.633680. PMC 8021898. PMID 33833683.

- ^ a b Cheema HA, Shafiee A, Athar M, Shahid A, Awan RU, Afifi AM, et al. (February 2023). "No evidence of clinical efficacy of famotidine for the treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J Infect. 86 (2): 154–225. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.11.022. PMC 9711899. PMID 36462586.

- ^ a b Kow CS, Ramachandram DS, Hasan SS (September 2023). "Famotidine: A potential mitigator of mast cell activation in post-COVID-19 cognitive impairment". J Psychosom Res. 172: 111425. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111425. PMC 10292911. PMID 37399740.

- ^ a b Yang H, George SJ, Thompson DA, Silverman HA, Tsaava T, Tynan A, et al. (May 2022). "Famotidine activates the vagus nerve inflammatory reflex to attenuate cytokine storm". Mol Med. 28 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s10020-022-00483-8. PMC 9109205. PMID 35578169.

- ^ Salvucci F, Codella R, Coppola A, Zacchei I, Grassi G, Anti ML, et al. (2023). "Antihistamines improve cardiovascular manifestations and other symptoms of long-COVID attributed to mast cell activation". Front Cardiovasc Med. 10: 1202696. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1202696. PMC 10388239. PMID 37529714.

- ^ Long B, Chavez S, Carius BM, Brady WJ, Liang SY, Koyfman A, et al. (June 2022). "Clinical update on COVID-19 for the emergency and critical care clinician: Medical management". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine (Review). 56: 158–170. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.036. PMC 8956349. PMID 35397357.

- ^ Andrade C (2013). "Famotidine Augmentation in Schizophrenia: Hope or Hype?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (9): e855–e858. doi:10.4088/JCP.13f08707. PMID 24107771. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "Famotidine". PetMD. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Famotidine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Famotidine at Wikimedia Commons