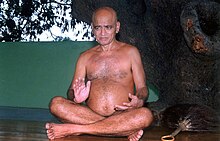

Digambara monk

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

A Digambara monk or Digambara Sādhu (also muni, sādhu) is a Sādhu in the Digambar tradition of Jainism, and as such an occupant of the highest limb of the four-fold sangha. Digambar Sādhus have 28 primary attributes which includes observance of the five supreme vows of ahimsa (non-injury), truth, non-thieving, celibacy and non-possession. A Digambar Sādhu is allowed to keep only a feather whisk, a water gourd and scripture with him.

In Jainism, those śrāvakas (householders) who wish to attain moksha (liberation) renounce all possessions and become an ascetic. According to the Jain text, Dravyasamgraha:[2]

Salutation to the Ascetic (Sādhu) abound in faith and knowledge, who incessantly practises pure conduct that surely leads to liberation.

— Dravyasaṃgraha (54)

Digambar Sādhus are also called nirgranth which means "one without any bonds".[3] The term originally applied to those of them who were on the point of attaining to omniscience, on the attainment of which they were called munis.[4]

Rishabhanath (the first Tirthankar) is said to be the first Digambar Sādhu of the present half cycle of time (avasarpini).[5] The presence of gymnosophists (naked philosophers) in Greek records as early as the fourth century BC, supports the claim of the Digambars that they have preserved the ancient Śramaṇa practice.[6] Āchārya Bhadrabāhu, Āchārya Kundakunda are two of the most revered Digambar Sādhus.

Mūla Guņas (Root virtues)

[edit]Every Digambara monk is required to observe 28 mula gunas (lit. twenty-eight primary attributes) compulsory. These are also called root-virtues, because it is said that in their absence other saintly virtues cannot be acquired. They are thus like the root, in the absence of which stems and branches tuneless come into being.[7] These twenty-eight primary attributes are: five supreme vows (mahāvrata); five regulations (samiti); five-fold control of the senses (pañcendriya nirodha); six essential duties (Şadāvaśyaka); and seven rules or restrictions (niyama).

Mahavratas

[edit]According to Acharya Samantabhadra's Ratnakaraņdaka śrāvakācāra:

Abstaining from the commitment of five kinds of sins (injury, falsehood, stealing, unchastity, and attachment) by way of doing these by oneself, causing these to be done, and approval when done by others, through the three kinds of activity (of body, speech, and thought), constitutes the great vows (mahāvrata) of celebrated ascetics.

— Ratnakaraņdaka śrāvakācāra (72)

- Ahimsa:

The first vow of a Digambara monk relates to the observance of ahiṃsā (non-injury). The monk is required to renounce himsa (injury) in all three forms:[8]

- Kŗita – He should not commit any act of himsa (injury) himself.

- Karita – He should not ask anyone else to do it for him.

- Anumodana – He should not, in any way, encourage commission of an act of himsa by saying or doing anything subsequent to the act.

There were five types of Ahimsa as per scriptures. These are the negation of following: Binding, beating, mutilating limbs, overloading, withholding food and drink. However over the centuries, Jain monks and philosophers have added stricter meanings and implementations. The concept of Ahimsa is specially well expanded and made diverse in the scriptures dating afterwards 10th century AD.

The monk should not injure any living being either in actions or thoughts. - Truth: A digambara monk must not say things which, though true, can lead to injury to living beings.

- Asteya (Non-thieving):

Not to take anything if not given. According to the Jain text, Tattvārthasūtra, five observances that strengthen this vow are:[9]

- Residence in a solitary place,

- Residence in a deserted habitation,

- Causing no hindrance to others,

- Acceptance of clean food, and

- Not quarrelling with brother monks.

- Brahmacharya: Brahmacharya refers to the self-control in respect of sex-function. It means avoiding all the kinds of natural and unnatural sex-gratification.[10]

- Aparigraha: Renunciation of worldly things and foreign natures, external and internal.[7]

Fivefold regulation of activities

[edit]- irya samiti

A digambara monk does not move about in the dark, nor on grass, but only along a path which is much trodden by foot. While moving, he has to observe the ground in front of him, to the extent of four cubits (2 yards), so as to avoid treading over any living being.[14] This samiti (control) is transgressed by:[15]- not being careful enough in looking at the ground in front, and

- sight-seeing along the route.

- bhasha samiti

Not to criticise anyone or speak bad words. - eshana

The observance of the highest degree of purity in the taking of food is eshana samiti. The food should be free from four kinds of afflictions to tarasa jīva (living beings possessing two or more senses), viz- pain or trouble,

- cutting, piercing etc.,

- distress, or mental suffering, and

- destruction or killing

- adan-nishep

To be careful in lifting and laying down things.[16] - pratişthāpanā

To dispose of the body waste at a place free from living beings.[17]

Strict control of five senses

[edit]Panchindrinirodh

This means renouncing all things which appeals to the mind through the senses.[17] This means shedding all attachment and aversion towards the sense-objects pertaining to

- touch (sparśana)

- taste (rasana)

- smell (ghrāņa)

- sight (chakşu)

- hearing (śrotra)[2]

Six Essential Duties

[edit]- Samayika (Equanimous dispassion) The monk is required to spend about six gharis (a ghari = 24 minutes) three times a day, that is, morning, noon, and evening, in practising equanimous dispassion.[17][18]

- stuti

Worship of the four and twenty Tirthankaras - vandan

To pay obeisances to siddhas, arihantas and acharya - Pratikramana

Self-censure, repentance; to drive oneself away from the multitude of karmas, virtuous or wicked, done in the past.[19] - Pratikhayan

Renunciation - Kayotsarga

Giving up attachment to the body and meditate on soul. (Posture: rigid and immobile, with arms held stiffly down, knees straight, and toes directly forward)[6]

Seven rules or restrictions (niyama)

[edit]- adantdhavan

Not to use tooth powder to clean teeth. - bhushayan

To rest only on earth or a wooden pallet. - Asnāna

Non-bathing. A digambara monk does not take baths. In his book "Sannyāsa Dharma", Champat Rai Jain writes:The saint is not allowed to bathe. For that will be fixing his attention on the body. There is no question of dirt or untidiness. He has no time to think of bathing or of cleaning his teeth. He has to prepare himself for the greatest contest in his career, namely, the struggle against Death, and cannot afford to waste his time and opportunity in attending to the beautification and embellishment of his outward person. Nay, he knows fully that death appears only in the form of the physical person which is a compound and, as such, liable by nature to dissolution and disintegration.[20]

- ekasthiti-bhojana

Taking food in a steady, standing posture.[1] - ahara

The monk consumes food and water once a day. He accepts pure food free from forty-six faults (doşa), thirty-two obstructions (antarāya), and fourteen contaminations (maladoşa).[note 1] - Keśa-lonch

To pluck hair on the head and face by hand.[2] - nāgnya

To renounce clothes.

Dharma

[edit]According to Jain texts, the dharma (conduct) of a monk is tenfold, comprising ten excellencies or virtues.[21]

- Forbearance: The absence of defilement such as anger in the ascetic, who goes out for food for preserving the body, when he meets with insolent words, ridicule or derision, disgrace, bodily torment and so on from vicious people.

- Modesty (humility): Absence of arrogance or egotism on account of high birth, rank and so on.

- Straightforwardness: Behaviour free from crookedness.

- Purity: Freedom from greed.

- Truth: Using chaste words in the presence of noble persons.

- Self-restraint: Desisting from injury to life-principles and sensual pleasures while engaged in careful activity.

- Supreme austerity: Undergoing penance in order to destroy the accumulated karmas is austerity. Austerity is of twelve kinds.

- Gift- Giving or bestowing knowledge etc. appropriate to saints.

- Non-attachment: giving up adornment of the body and the thought ‘this is mine’.

- Perfect celibacy: It consists in not recalling pleasure enjoyed previously, not listening to stories of sexual passion (renouncing erotic literature), and renouncing bedding and seats used by women.

The word 'perfect' or 'supreme' is added to every one of the terms in order to indicate the avoidance of temporal objectives.

Twenty-two afflictions

[edit]Jain texts list down twenty-two hardships (parīşaha jaya) that should be endured by an ascetic who wish to attain moksha (liberation). These are required to be endured without any anguish.[22][23]

- kşudhā – hunger;

- trişā – thirst;

- śīta – cold;

- uşņa – heat;

- dañśamaśaka – insect-bite;

- nāgnya – nakedness;

- arati – displeasure;

- strī – disturbance due to feminine attraction;[note 2]

- caryā – discomfort arising from roaming;

- nişadhyā – discomfort of postures;

- śayyā – uncomfortable couch;

- ākrośa – scolding, insult;

- vadha – assault, injury;

- yācanā – determination not to beg for favours;

- alābha – lack of gain; not getting food for several days in several homes;

- roga – illness;

- traņasparśa – pain inflicted by blades of grass;

- mala – dirt of the body;

- satkāra-puraskāra – (absence of) reverence and honour;

- prajñā – (conceit of) learning;

- ajñāna – despair or uneasiness arising from failure to acquire knowledge;

- adarśana – disbelief due to delay in the fruition of meritorious deeds.

External austerities

[edit]According to the Jain text, Sarvārthasiddhi, "Affliction is what occurs by chance. Mortification is self-imposed. These are called external, because these are dependent on external things and these are seen by others."[25]

Several Jain texts including Tattvarthsutra mentions the six external austerities that can be performed:[26]

- 'Fasting' to promote self-control and discipline, destruction of attachment.

- 'Diminished diet' is intended to develop vigilance in self-control, suppression of evils, contentment and study with ease.

- 'Special restrictions' consist in limiting the number of houses etc. for begging food, and these are intended for overcoming desire.

- 'Giving up stimulating and delicious food' such as ghee, in order to curb the excitement caused by the senses, overcome sleep, and facilitate study.

- Lonely habitation: The ascetic has to 'make his abode in lonely places' or houses, which are free from insect afflictions, in order to maintain without disturbance celibacy, study, meditation and so on.

- Standing in the sun, dwelling under trees, sleeping in an open place without any covering, the different postures – all these constitute the sixth austerity, namely 'mortification of the body'.

Jain monks and advanced laypeople avoid eating after sunset, observing a vow of ratri-bhojana-tyaga-vrata.[27] Digambara monks observe a stricter vow by eating only once a day.[27]

Āchārya

[edit]

Āchārya means the Chief Preceptor or the Head. Āchārya has thirty-six primary attributes (mūla guņa) consisting in:[28]

- Twelve kinds of austerities (tapas);

- Ten virtues (dasa-lakşaņa dharma);

- Five kinds of observances in regard to faith, knowledge, conduct, austerities, and power. These are:[29]

- Darśanācāra: Believing that the pure Self is the only object belonging to the self and all other objects, including the karmic matter (dravya karma and no-karma) are alien; further, believing in the six substances (dravyas), seven Realities (tattvas) and veneration of Jina, Teachers, and the Scripture, is the observance in regard to faith (darśanā).

- Jñānācāra: Reckoning that the pure Self has no delusion, is distinct from attachment and aversion, knowledge itself, and sticking to this notion always is the observance in regard to knowledge (jñānā).

- Cāritrācāra: Being free from attachment etc. is right conduct which gets obstructed by passions. In view of this, getting always engrossed in the pure Self, free from all corrupting dispositions, is the observance in regard to conduct (cāritrā).

- Tapācāra: Performance of different kinds of austerity is essential to spiritual advancement. Performance of penances with due control of senses and desires constitutes the observance in regard to austerities (tapā).

- Vīryācāra: Carrying out the above-mentioned four observances with full vigour and intensity, without digression and concealment of true strength, constitutes the observance in regard to power (vīryā).

- Six essential duties (Şadāvaśyaka); and

- Gupti: Controlling the threefold activity of:[16]

- the body;

- the organ of speech; and

- the mind.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A digambara monk's food intake is also explained as:

- Gochari. This signifies that, as a cow does not concern herself with the beauty, ornaments, richness of apparel, and the like of the person who comes to feed her, so is the conduct of a monk.

- Analogy of a bee's action. As the bee gathers honey without damaging any of the flowers from which it extracts it, in the same way the saint takes his food without causing injury or inconvenience to any of the givers.

- Filling the pit. As people fill a pit without regard to the beauty or ugliness of tho material with which it is to be filled, in the same way the saint should look upon his stomach which is to be filled regardless of the consideration that the food is not toothsome.

- ^ Prof. S.A. Jain in his English translation of the Jain text, Sarvarthasiddhi writes:

In the presence of lovely, intoxicated women in the bloom of youth, the ascetic residing in lonely bowers, houses, etc. is free from agitation or excitement, even though he is disturbed by them. Similarly, he subdues agitations of his senses and his mind like the tortoise covered by his shell. And the smile, charming talk, amorous glances and laughter, lustful slow movement of women and the arrows of Cupid have no effect on him. This must be understood as the conquest of the disturbance caused by women.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Jain 2013, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Jain 2013, p. 196.

- ^ B.K. Jain 2013, p. 62.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 19.

- ^ B.K. Jain 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b Zimmer 1953, p. 210.

- ^ a b C.R. Jain 1926, p. 26.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 28.

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 95.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 29.

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka (in Sanskrit) (new ed.). pp. 132.

- ^ Baruah, Bibhuti (2000). Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. Sarup & Sons. p. 15. ISBN 9788176251525.

- ^ Hirakawa, Akira (1993). A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 100. ISBN 9788120809550.

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 55.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 62.

- ^ a b Jain 2013, p. 125.

- ^ a b c C.R. Jain 1926, p. 37.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 143.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 191.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 45.

- ^ C.R. Jain 1926, p. 49.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 156.

- ^ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 252-256.

- ^ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 252.

- ^ S.A. Jain 1992, p. 263.

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 133.

- ^ a b Jaini 2000, p. 285.

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 189-191.

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 190.

Sources

[edit]- Jain, Babu Kamtaprasad (2013), Digambaratva aur Digambar muni, Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 978-81-263-5122-0

- Jain, Champat Rai (1926), Sannyasa Dharma,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. (2000), Collected Papers On Jain Studies (First ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6

- Jain, S.A. (1992), Reality (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Vijay K. (2013), Ācārya Nemichandra's Dravyasaṃgraha, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363952,

Non-copyright

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra (1st ed.), Uttarakhand: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.