Dies irae

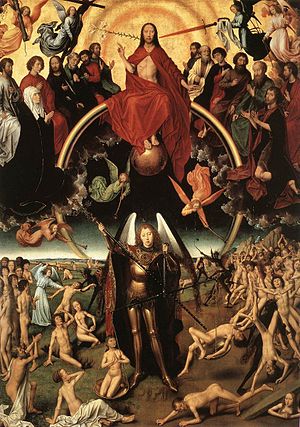

Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) is a famous thirteenth century Latin hymn thought to be written by Thomas of Celano.[1] It is a medieval Latin poem characterized by its accentual stress and its rhymed lines. The metre is trochaic. The poem describes the day of judgment, the last trumpet summoning souls before the throne of God, where the saved will be delivered and the unsaved cast into eternal flames.

The hymn is best known from its use as a sequence in the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. It was removed from the ordinary form of the Roman Rite mass in the liturgical reform of 1969–1970, but was retained as a hymn of the Divine Office. It can also still be heard when the 1962 form of the Mass is used. An English version of it is found in various missals used in the Anglican Communion.

Use in the Catholic liturgy

Those familiar with musical settings of the Requiem Mass—such as those by Mozart or Verdi—will be aware of the important place Dies Iræ held in the liturgy. Nevertheless the "Consilium for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Liturgy" – the Vatican body charged with drafting and implementing reforms to the Catholic Liturgy ordered by the Second Vatican Council – felt the funeral rite was in need of reform and eliminated the sequence from the ordinary rite. The architect of these reforms, Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, explains the mind of the members of the Consilium:

- They got rid of texts that smacked of a negative spirituality inherited from the Middle Ages. Thus they removed such familiar and even beloved texts as the Libera me, Domine, the Dies Iræ, and others that overemphasized judgment, fear, and despair. These they replaced with texts urging Christian hope and arguably giving more effective expression to faith in the resurrection.[2]

It remained as the sequence for the Requiem Mass in the Roman Missal of 1962 (the last edition before the Second Vatican Council) and so is still heard in churches where the Tridentine Latin liturgy is celebrated.

The Dies Irae is still suggested in the Liturgy of the Hours during last week before Advent as the opening hymn for the Office of Readings, Lauds and Vespers (divided into three parts).[3]

The text

The Latin text below is taken from the Requiem Mass in the 1962 Roman Missal. The first English version below, translated by William Josiah Irons in 1849,[4] replicates the rhyme and metre of the original. The second English version is a more formal equivalence.

| 1 | Dies iræ ! dies illa Solvet sæclum in favilla: Teste David cum Sibylla ! |

Day of wrath! O day of mourning! See fulfilled the prophets' warning, Heaven and earth in ashes burning! |

The day of wrath, that day Will dissolve the world in ashes As foretold by David and the sibyl! |

| 2 | Quantus tremor est futurus, Quando iudex est venturus, Cuncta stricte discussurus ! |

Oh, what fear man's bosom rendeth, when from heaven the Judge descendeth, on whose sentence all dependeth. |

How much tremor there will be, when the judge will come, investigating everything strictly! |

| 3 | Tuba, mirum spargens sonum Per sepulchra regionum, Coget omnes ante thronum. |

Wondrous sound the trumpet flingeth; through earth's sepulchers it ringeth; all before the throne it bringeth. |

The trumpet, scattering a wondrous sound through the sepulchres of the regions, will summon all before the throne. |

| 4 | Mors stupebit, et natura, Cum resurget creatura, Iudicanti responsura. |

Death is struck, and nature quaking, all creation is awaking, to its Judge an answer making. |

Death and nature will marvel, when the creature arises, to respond to the Judge. |

| 5 | Liber scriptus proferetur, In quo totum continetur, Unde mundus iudicetur. |

Lo! the book, exactly worded, wherein all hath been recorded: thence shall judgment be awarded. |

The written book will be brought forth, in which all is contained, from which the world shall be judged. |

| 6 | Iudex ergo cum sedebit, Quidquid latet, apparebit: Nil inultum remanebit. |

When the Judge his seat attaineth, and each hidden deed arraigneth, nothing unavenged remaineth. |

When therefore the judge will sit, whatever hides will appear: nothing will remain unpunished. |

| 7 | Quid sum miser tunc dicturus ? Quem patronum rogaturus, Cum vix iustus sit securus ? |

What shall I, frail man, be pleading? Who for me be interceding, when the just are mercy needing? |

What am I, miserable, then to say? Which patron to ask, when [even] the just may [only] hardly be sure? |

| 8 | Rex tremendæ maiestatis, Qui salvandos salvas gratis, Salva me, fons pietatis. |

King of Majesty tremendous, who dost free salvation send us, Fount of pity, then befriend us! |

King of tremendous majesty, who freely savest those that have to be saved, save me, source of mercy. |

| 9 | Recordare, Iesu pie, Quod sum causa tuæ viæ: Ne me perdas illa die. |

Think, good Jesus, my salvation cost thy wondrous Incarnation; leave me not to reprobation! |

Remember, merciful Jesus, that I am the cause of thy way: lest thou lose me in that day. |

| 10 | Quærens me, sedisti lassus: Redemisti Crucem passus: Tantus labor non sit cassus. |

Faint and weary, thou hast sought me, on the cross of suffering bought me. shall such grace be vainly brought me? |

Seeking me, thou sat tired: thou redeemed [me] having suffered the Cross: let not so much hardship be lost. |

| 11 | Iuste iudex ultionis, Donum fac remissionis Ante diem rationis. |

Righteous Judge! for sin's pollution grant thy gift of absolution, ere the day of retribution. |

Just judge of revenge, give the gift of remission before the day of reckoning. |

| 12 | Ingemisco, tamquam reus: Culpa rubet vultus meus: Supplicanti parce, Deus. |

Guilty, now I pour my moaning, all my shame with anguish owning; spare, O God, thy suppliant groaning! |

I sigh, like the guilty one: my face reddens in guilt: Spare the supplicating one, God. |

| 13 | Qui Mariam absolvisti, Et latronem exaudisti, Mihi quoque spem dedisti. |

Thou the sinful woman savedst; thou the dying thief forgavest; and to me a hope vouchsafest. |

Thou who absolved Mary, and heardest the robber, gavest hope to me, too. |

| 14 | Preces meæ non sunt dignæ: Sed tu bonus fac benigne, Ne perenni cremer igne. |

Worthless are my prayers and sighing, yet, good Lord, in grace complying, rescue me from fires undying! |

My prayers are not worthy: however, thou, Good [Lord], do good, lest I am burned up by eternal fire. |

| 15 | Inter oves locum præsta, Et ab hædis me sequestra, Statuens in parte dextra. |

With thy favored sheep O place me; nor among the goats abase me; but to thy right hand upraise me. |

Grant me a place among the sheep, and take me out from among the goats, setting me on the right side. |

| 16 | Confutatis maledictis, Flammis acribus addictis: Voca me cum benedictis. |

While the wicked are confounded, doomed to flames of woe unbounded call me with thy saints surrounded. |

Once the cursed have been rebuked, sentenced to acrid flames: Call thou me with the blessed. |

| 17 | Oro supplex et acclinis, Cor contritum quasi cinis: Gere curam mei finis. |

Low I kneel, with heart submission, see, like ashes, my contrition; help me in my last condition. |

I meekly and humbly pray, [my] heart is as crushed as the ashes: perform the healing of mine end. |

| 18 | Lacrimosa dies illa, qua resurget ex favilla iudicandus homo reus. Huic ergo parce, Deus: |

Ah! that day of tears and mourning! From the dust of earth returning man for judgment must prepare him; Spare, O God, in mercy spare him! |

Tearful will be that day, on which from the ashes arises the guilty man who is to be judged. Spare him therefore, God. |

| 19 | Pie Iesu Domine, dona eis requiem. Amen. |

Lord, all pitying, Jesus blest, grant them thine eternal rest. Amen. |

Merciful Lord Jesus, grant them rest. Amen. |

Because the last two stanzas differ markedly in structure from the preceding stanzas, some scholars consider them to be an addition made in order to suit the great poem for liturgical use. The penultimate stanza Lacrimosa discards the consistent scheme of rhyming triplets in favor of a pair of rhyming couplets. The last stanza Pie Jesu abandons rhyme for assonance, and, moreover, its lines are catalectic.

In 1970, the Dies Iræ was removed from the Missal and since 1971 has been proposed ad libitum as a hymn for the Liturgy of the Hours at the Office of Readings, Lauds and Vespers. For this purpose stanza 19 was deleted and the poem divided into three sections: 1–6 (for the Office of Readings), 7–12 (for Lauds) and 13–18 (for Vespers). In addition Qui Mariam absolvisti in stanza 13 was replaced by Peccatricem qui solvisti so that that line would now mean, "You who freed/absolved the sinful woman". In addition a doxology is given after stanzas 6, 12 and 18:[3]

| O tu, Deus majestatis, alme candor Trinitatis nos coniunge cum beatis. Amen. |

O God of majesty nourishing light of the Trinity join us with the blessed. Amen. |

O thou, God of majesty, gracious splendour of the Trinity conjoin us with the blessed. Amen. |

Inspiration and other translations

A major inspiration of the hymn seems to have come from the Vulgate translation of Zephaniah 1:15–16:

- Dies iræ, dies illa, dies tribulationis et angustiæ, dies calamitatis et miseriæ, dies tenebrarum et caliginis, dies nebulæ et turbinis, dies tubæ et clangoris super civitates munitas et super angulos excelsos.

- That day is a day of wrath, a day of tribulation and distress, a day of calamity and misery, a day of darkness and obscurity, a day of clouds and whirlwinds, a day of the trumpet and alarm against the fenced cities, and against the high bulwarks. (Douay–Rheims Bible)

Other images come from Revelation 20:11–15 (the book from which the world will be judged), Matthew 25:31–46 (sheep and goats, right hand, contrast between the blessed and the accursed doomed to flames), 1 Thessalonians 4:16 (trumpet), 2 Peter 3:7 (heaven and earth burnt by fire), Luke 21:26–27 ("men fainting with fear ... they will see the Son of Man coming"), etc.

From the Jewish liturgy, the prayer Unetanneh Tokef also appears to have been a source: "We shall ascribe holiness to this day, For it is awesome and terrible"; "the great trumpet is sounded", etc.

A number of English translations of the poem have been written and proposed for liturgical use. A very loose Protestant version was made by John Newton; it opens:

- Day of judgment! Day of wonders!

- Hark! the trumpet's awful sound,

- Louder than a thousand thunders,

- Shakes the vast creation round!

- How the summons wilt the sinner's heart confound!

Jan Kasprowicz, a Polish poet, wrote a hymn entitled Dies irae which describes the Judgment day. The first six lines (two stanzas) follow the original hymn's metre and rhyme structure, and the first stanza translates to "The trumpet will cast a wondrous sound".

The American writer Ambrose Bierce published a satiric version of the poem in his 1903 book Shapes of Clay, preserving the original metre but using humorous and sardonic language; for example, the second verse is rendered:

- Ah! what terror shall be shaping

- When the Judge the truth's undraping –

- Cats from every bag escaping!

Rev. Bernard Callan (1750-1804), an Irish priest and poet, translated it into Gaelic around 1800. His version is included in the Gaelic prayer book, The Spiritual Rose.[5]

Manuscript sources

The oldest text of the sequence is found, with slight verbal variations, in a 13th century manuscript in the Biblioteca Nazionale at Naples. It is a Franciscan calendar missal that must date between 1253–1255 for it does not contain the name of Clare of Assisi, who was canonized in 1255, and whose name would have been inserted if the manuscript were of later date.

Musical settings

In four-line neumatic notation, the Gregorian chant of the sequence begins:

In 5-line staff notation, the same appears:

The words have often been set to music as part of the Requiem service, originally as a sombre plainchant. It also formed part of the traditional Catholic liturgy of All Souls' Day. Music for the Requiem Mass has been composed by many composers, including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart as well as Hector Berlioz, Giuseppe Verdi, and Igor Stravinsky.

The traditional Gregorian melody has also been used as a musical quotation in a number of other classical compositions, among them:

- Thomas Adès – Living Toys[citation needed]

- Charles-Valentin Alkan – Symphony for Solo Piano, Op. 39;[citation needed] Souvenirs: Trois morceaux dans le genre pathétique, Op. 15 (No. 3: Morte)

- David Baker – Fantasy on Themes from Masque of the Red Death Ballet[citation needed]

- Arvo Part - Te Deum

- Ernest Bloch – Suite Symphonique [6]

- Hector Berlioz – Symphonie fantastique

- Johannes Brahms – Klavierstück, Op. 118, No. 6[citation needed]

- Antoine Brumel – Dies Irae[citation needed]

- Sergei Lyapunov - Études d'exécution transcendante, Op. 11 No. 3 "Pealing of Bells"[citation needed]

- Wendy Carlos – Carnival of the Animals – Part Two – 10. Shark[citation needed]

- Elliott Carter – In Sleep, In Thunder, #4[citation needed]

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier – Grand Office des Morts[citation needed]

- George Crumb – Black Angels, Makrokosmos Volume II[citation needed], Star Child[citation needed]

- Luigi Dallapiccola – Canti di prigionia[citation needed]

- Michael Daugherty – Metropolis Symphony 5th movement, "Red Cape Tango";[7] Dead Elvis[citation needed]

- Raymond Deane – Seachanges[citation needed]

- Ernő Dohnányi – Rhapsody in E-flat minor, Op. 11, No. 4[citation needed]

- Antonín Dvořák – Symphony No. 7 in D minor, movement 1[citation needed]

- Martin Ellerby – Paris Sketches, movement 3[citation needed]

- Antonio Estévez – Cantata Criolla (1954)[citation needed]

- Jean Françaix – Cinq poemes de Charles d'Orléans[citation needed]

- Diamanda Galás – Masque Of The Red Death: Part I – The Divine Punishment and Saint Of The Pit: "L'Héautontimorouménos" (Self-Tormentor)[citation needed]

- Robert Gerhard – Piano concerto[citation needed]

- Alexander Glazunov – Orchestral suite From the Middle Ages, Op. 79[citation needed]

- Leopold Godowsky – Piano sonata in E minor, movement 5[citation needed]

- Berthold Goldschmidt – Beatrice Cenci opera[citation needed]

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk - Cakewalk suite[citation needed]

- Charles Gounod – Faust opera, Act IV; Mors et Vita[citation needed]

- Sofia Gubaidulina – Am Rande des Abgrunds (On the edge of abyss), for 7 celli and 2 aquaphones[citation needed]

- Joseph Haydn – Symphony No. 103, "The Drumroll"

- Heinz Holliger – Violin Concerto, 2nd movement[citation needed]

- Vagn Holmboe – Symphony No. 10, 1st and 4th movements;[citation needed] Symphony No. 11, 1st movement[citation needed]

- Arthur Honegger – La Danse des Morts[citation needed]

- Karl Jenkins – Requiem[citation needed]

- Miloslav Kabeláč – Symphony No. 8 Antiphonies[citation needed]

- Dmitry Kabalevsky - Cello concerto no. 2 in C minor, Op. 77[citation needed]

- Aram Khachaturian – Symphony No. 2 The Bell Symphony;[citation needed] Spartacus[citation needed]

- György Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre[citation needed]

- Franz Liszt – Dante Symphony;[citation needed] Totentanz

- Charles Martin Loeffler – One Who Fell in Battle, Rhapsodies for oboe, viola, and piano, 1st movement, and several songs[citation needed]

- Jean-Baptiste Lully – Dies Irae[citation needed]

- Gustav Mahler – Symphony No. 2, movements 1, 3, and 5

- Bohuslav Martinů – Cello concerto no. 2, final movement[citation needed]

- Nikolai Medtner – Piano quintet in C major, Op. posth.[citation needed]

- Modest Mussorgsky – Night on Bald Mountain;[citation needed] Songs and Dances of Death;[citation needed] Intermezzo in modo classico[citation needed]

- Nikolai Myaskovsky – Piano sonata no. 2;[citation needed] Symphony no. 6[citation needed]

- Krzysztof Penderecki – Dies Irae[citation needed]

- Ildebrando Pizzetti – Requiem;[citation needed] Assassinio nella cattedrale[citation needed]

- Sergei Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 1, Op. 13; Symphony No. 2, Op. 27; Symphony No. 3, Op. 44; Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28;[citation needed] Isle of the Dead, Op. 29; Prelude in E minor, Op. 32, No. 4;[citation needed] The Bells choral symphony, Op. 35; Études-Tableaux, Op. 39, No. 2;[citation needed] Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43; Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

- Ottorino Respighi – Brazilian Impressions[citation needed]

- Marcel Rubin – Symphony No. 4, 2nd movement (Dies Irae)[citation needed]

- Camille Saint-Saëns – Danse Macabre;[citation needed] Requiem;[citation needed] Symphony No. 3 ("Organ Symphony")

- Aulis Sallinen – Dies Irae, Op. 47[citation needed]

- Ernest Schelling – Impressions from an Artist's Life[citation needed]

- William Schmidt – Tuba mirum[citation needed]

- Alfred Schnittke – Symphony No. 1, movement 4[citation needed]

- Peter Sculthorpe – Memento Mori (1993)[citation needed]

- Dmitri Shostakovich – Music for Hamlet;[citation needed] Symphony No. 14; "Dance of Death" from Aphorisms[citation needed]

- Jean Sibelius – Lemminkäinen Suite[citation needed]

- Stephen Sondheim – Sweeney Todd – quoted in "The Ballad of Sweeney Todd" and the accompaniment to "Epiphany"[8]

- Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji – Variazioni e fuga triplice sopra "Dies iræ" per pianoforte (1923–26); Sequentia cyclica super "Dies iræ" ex Missa pro defunctis in clavicembali usum (1948–49)

- Ronald Stevenson – Passacaglia on DSCH (1962–63)[citation needed]

- Richard Strauss – Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks;[citation needed] "Dance of the seven veils" from Salome[citation needed]

- Igor Stravinsky – The Rite of Spring (sacrifice intro);[citation needed] Three pieces for String Quartet (III, "Canticle");[citation needed] Histoire du soldat;[citation needed] Wind Octet, (Tema con variazioni)[citation needed]

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – "Modern Greek Song", Op. 16, No. 6;[citation needed] Marche funèbre, Op. 21, No. 4 from "Six Morceaux" for piano;[citation needed] Grand Sonata, Op. 37, for piano;[citation needed] Manfred Symphony;[citation needed] Orchestral Suite No. 3, Op. 55[citation needed]

- Frank Ticheli – Vesuvius[citation needed]

- Loris Tjeknavorian – Symphony No 3 (Peace with all Men)[citation needed]

- Ralph Vaughan Williams – Five Tudor Portraits[citation needed]

- Adrian Williams – Dies Irae[citation needed]

- James Yannatos – Trinity Mass[citation needed]

- Eugène Ysaÿe – Sonata in A minor, Op. 27, No. 2 "Obsession"

Literary references

- Walter Scott used the first two stanzas in the sixth canto of his narrative poem "The Lay of the Last Minstrel" (1805).

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used the first, the sixth and the seventh stanza of the hymn in the scene "Cathedral" in the first part of his drama Faust (1808).

- Italian poet Giuseppe Giusti composed in 1835 the satirical poem Il "Dies iræ" on the occasion of the death of Francis II, Emperor of Austria.

- In José Rizal's 1887 novel Noli Me Tangere, the last two lines of the sixth stanza of the hymn ("Quidquid latet, apparebit, Nil inultum remanebit") are used as the title of the 54th chapter of his novel, depicting how Elias discovers who the descendant of the man who ruined their family is.

- Oscar Wilde composed a Sonnet on Hearing the Dies Irae Sung in the Sistine Chapel, contrasting the "terrors of red flame and thundering" depicted in the hymn with images of "life and love".

- In Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera, Erik (the Phantom) has the chant displayed on the wall of his funereal bedroom.[9]

- Kurt Vonnegut wrote Stone, Time, and Elements: A Humanist Requiem in opposition to the classical Requiem and in particular to the Dies Irae, which he found "vengeful and sadistic" (and mistakenly reputed a "piece of poetry by committee from the Council of Trent"). His Requiem was set to music by Edgar David Grana.

- Dies Irae was a title D. H. Lawrence considered for the novel that became Women in Love (1920).[citation needed]

- Thomas Pynchon's 1963 novel V. includes direct references to Dies Irae in chapter 9 – "Somewhere in the house (though he may have dreamed that too) a chorus had begun singing a Dies Irae in plainsong."

- Arthur C. Clarke's 1968 novel 2001: A Space Odyssey has the main character, David Bowman, listening to a recording of it on the spaceship Discovery One on his way to Saturn.

- The title of the 1976 novel Deus Irae, a collaboration between Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny, is a play on the name of the hymn Dies Irae.

- In Umberto Eco's 1980 novel The Name of the Rose, Adso has a dream or vision based on the Coena Cypriani while the monks around him chant the Dies Irae.

- In Patrick O'Brians novel, The Letter of Marque (1988): "and some moments later the after part of the ship, usually quiet with a following wind and a moderate sea, was filled with a great deep roaring Dies Irae that went on and on, quite startling the quarterdeck." (Played by the character Dr Maturin on his cello.)

- "Dies irae, dies illa when the absent shall be present and the present absent...in albums, in desk drawers, this picture and thousands like it have subtly matured, metamorphosed." Age of Iron (1990) by J. M. Coetzee

- In Anne Rice's 1998 novel The Vampire Armand , when Amadeo and other apprentices were captured by the Santino's satanic coven of vampires, they would mock Amadeo/Armand by singing this hymn.

References in popular culture

- Film composer Dimitri Tiomkin uses the Dies Irae in the scene in It's a Wonderful Life where George Bailey is fleeing to the bridge after seeing Pottersville.[10]

- Film composer Bernard Herrmann uses the Dies Irae in the skeleton sequence from the 1963 fantasy film Jason and the Argonauts.[citation needed]

- In Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film The Seventh Seal, the traditional Gregorian Dies Irae is used throughout the film.

- Stephen Schwartz and Alan Menken use parts of Dies Irae in their soundtrack to Disney's 1996 film The Hunchback of Notre Dame.[citation needed]

- "Lacrimosa" by singer/songwriter Regina Spektor centers around the eighteenth stanza of the poem. The song is written from the point of view of Icarus, the son of Daedalus from Greek mythology, as he is falling to the earth.[citation needed]

- In Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), the last stanza (Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem) is chanted by monks hitting themselves with boards.[citation needed]

- Two songs in the 1993 soundtrack of the film The Nightmare Before Christmas, "Making Christmas" and "Sally's Song," are based on the Dies Irae melody.[citation needed]

- Wendy Carlos used the main subject in her composition "Country Lane" from the album entitled A Clockwork Orange: Wendy Carlos's Complete Original Score (1972).[citation needed]

- In the 1996 Broadway musical Rent and its 2004 film adaptation, at the beginning of the number "La Vie Boheme", Collins and Roger quote the Dies Irae (along with the Kyrie Eleison and the Mourners' Kaddish) as part of a mock requiem in honor of "the death of Bohemia".[citation needed]

- In Stanley Kubrick's 1980 film The Shining, the main theme is based on Hector Berlioz' interpretation of the Dies Irae as he used it in his "Symphonie fantastique".

- The seventh track of Bathory's 1988 black metal album Blood Fire Death is entitled "Dies Irae".

References

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy : 1948–1975, (The Liturgical Press, 1990), Chap. 46.II.1, p. 773.

- ^ a b Liturgia Horarum IV, (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2000), p. 489.

- ^ This translation appears in the English Missal and also The Hymnal 1940 of the Episcopal Church in the USA.

- ^ F 2.22: The Spiritual Rose ed. Malachy McKenna at School of Celtic Studies - Scoil an Léinn Cheiltigh Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies Institiúid Ard-Léinn Bhaile Átha Cliath website

- ^ Simmons, Walter. Voices in the Wilderness: Six American Neo-romantic Composers. Scarecrow Press, 2004. ISBN 0810848848

- ^ About this Recording - 8.559635 - DAUGHERTY, M.: Metropolis Symphony / Deus ex Machina (T. Wilson, Nashville Symphony, Guerrero)

- ^ Zadan, Craig (1989). Sondheim & Co. 2nd edition. Perennial Library. p. 248. ISBN 0-06-091400-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Leroux, Gaston. "The Phantom of the Opera". Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1985, p. 139

- ^ http://www.zuzu.net/essays/music.html

External links

- Dies Iræ, Franciscan Archive. Includes two Latin versions and a literal English translation.

- Podies Irae – Film Score Monthly podcast highlighting the use of Dies Irae in concert and film music.