Jugend (magazine)

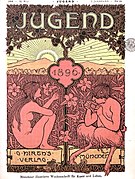

A Fritz Dannenberg 1897 poster promoting the magazine | |

| Editor | Franz Schoenberner |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Founder | Georg Hirth |

| First issue | 1896 |

| Final issue | 1940 |

| Country | Germany |

| Based in | Munich |

| Language | German |

Jugend (German for 'Youth') (1896–1940) was an influential German arts magazine. Founded in Munich by Georg Hirth who edited it until his death in 1916, the weekly was originally intended to showcase German Arts and Crafts, but became famous for showcasing the German version of Art Nouveau instead. It was also famed for its "shockingly brilliant covers and radical editorial tone" and for its avant-garde influence on German arts and culture for decades, ultimately launching the eponymous Jugendstil ('Youth Style') movement in Munich, Weimar, and Germany's Darmstadt Artists' Colony.[1]

The magazine, along with several others that launched more or less concurrently, including Pan, Simplicissimus, Dekorative Kunst ('Decorative Art') and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration ('German Art and Decoration')[2] collectively roused interest among wealthy industrialists and the aristocracy, which further spread interest in Jugendstil from 2D art (graphic design) to 3D art (architecture), as well as more applied art.[2] Germany's gesamtkunstwerk ('synthesized artwork') tradition eventually merged and evolved those interests into the Bauhaus movement.[2]

History

[edit]Georg Hirth founded the journal in 1896 to launch a new cultural renaissance in Munich. From the start, he intended the magazines to be collectible, and therefore distinct.[3] In the first seven volumes, he featured more than 250 artists, the vast majority unknown.[3] After the First World War, the magazine went out of style with young artists.[3] Among its regular contributors was Bruno Paul.

Hirth was chief editor of the magazine for 20 years until his death in 1916. At that time, Franz Schoenberner was made publisher, and an array of art editors played a role in its cover and illustrations, including Hans E. Hirsch, Theodore Riegler, and Wolfgang Petzet, with Fritz von Ostini and Albert Matthäi editing the text, and Franz Langheinrich serving as photo editor.

Associated influences

[edit]In its early years, Jungend provided a nostalgic counter the rapid industrialization of Germany during the 1800s and, toward the end of the century, the shift in population from a romanticized, idyllic countryside to urban centers.[4]

As the early Arts and Crafts ambitions faded and German Art Nouveau took hold of the magazine's aesthetic, iconic imagery of nude youth in idealized nature scenes were depicted more frequently.[5] Along with other symbols of nature at its most magical — nymphs, centaurs, and satyrs — the associations between Jugendstil and the Lebensreform ('life reform') movement, which encouraged a return to a "natural" life-style, grew.[5] In addition to modern illustrations and the ornamentation of Art Nouveau, the magazine featured impressionist and expressionist art, as well.

The journal also covered satirical and critical topics in culture, such as the increasing influence of the churches (especially Catholicism), and the political right in the Centre Party.[1] The Yale Literary Magazine critic summarized the editorial attitude by noting that "Jugend's political and social platform [was] one opposition—opposition to everything."[1] For all that, Jugend's contribution to the literature of the early modern period remained modest, especially compared to Albert Langen's competing journal Simplicissimus, which was also founded in 1896.

Jugend's editorial identity originally focused on national and Bavarian regional issues. That changed in the mid-1920s, when it began catering to, and then entered into dialogue with groups of young artists breaking with traditional approaches to art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the Jugendstil in multiple German cities, as well as a series of so-called secessions in Paris, Vienna, Munich, Berlin, Dresden, and elsewhere. After 1933, the magazine was forced to cater to the Nazis, which restricted its editorial vision to the neoclassical propaganda approved by the regime, in the Great German Art Exhibition[6] of 1937, which was presented in counterpoint to the 650 pieces confiscated from German museums in the Degenerate Art Exhibition.[7]

Legacy

[edit]- The use of integrating and matching typefaces into the illustration continues to influence graphic design.[8]

- Germany's gesamtkunstwerk ("synthesized artwork") tradition, which came to the fore in German Art Nouveau led to a reexamination of "how to reconcile art with industry, ornamentation with functionalism."[2]

Gallery

[edit]-

Vol. I, No. 12 (1896) by Ludwig von Zumbusch

-

Vol. I, No. 14 (1896) by Otto Eckmann

-

Sicilian Boy, a photograph by Wilhelm von Gloeden. Inspired Hans Christiansen's cover for Vol. I, No. 30 (1896). In a style reminiscent of the Lebensreform

-

Vol. I, No. 30 (1896) by Hans Christiansen

-

An 1897 poster for Jugend by Fritz Dannenberg. A black-and-white version of the image appeared in Vol. II, No. 1 (1897).

-

Vol. II, No. 30 (1897) by Ludwig Raders

-

Andromeda by Hans Christiansen. Used as cover for Vol. III, No. 48 (1898)

-

Loreley by Heinrich Kley. Appeared in Vol. XVI, No. 34 (1911)

-

Vol. XX, No. 1 (1915) by Paul Rieth. A German soldier

-

Vol. XXXV, No. 32 (1930) by Konrad Westermayr. A German soldier

See also

[edit]- Gesamtkunstwerk

- List of magazines in Germany

- Pan (magazine)

- Secession (art)

- Simplicissimus (magazine)

- Ulenspiegel

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Download Hundreds of Issues of Jugend, Germany's Pioneering Art Nouveau Magazine (1896–1940)". Open Culture. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ a b c d "Jugendstil: Art Nouveau in Germany, Austria: History, Characteristics". Art Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- ^ a b c "Jugend – Münchner illustrierte Wochenschrift für Kunst und Leben – digitized". Heidelberg University Library. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Pearce, Michael (2024-06-19). "Jugend: Youth, Spring, and Love". MutualArt. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- ^ a b Rosenman, Roberto (2017). "Art Nouveau Magazines". Vienna Secession. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

- ^ Simkin, John (June 2020) [September 1997]. "Great German Art Exhibition". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2021-07-02.

- ^ Goutam, Urvashi (2014). "Pedagogical Nazi Propaganda (1939–1945)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 75: 1018–1026. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44158487.

- ^ "Jugend – Nr. 24 1920 – Georg Hirth". A.W. Alexander. 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2021-07-01.

![Vol. I, No. 12 (1896) by Ludwig von Zumbusch [de]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Titelblatt_der_Zeitschrift_Jugend_1896%2C_Nr._12_von_Ludwig_von_Zumbusch.jpg/133px-Titelblatt_der_Zeitschrift_Jugend_1896%2C_Nr._12_von_Ludwig_von_Zumbusch.jpg)

![Vol. II, No. 30 (1897) by Ludwig Raders [de]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Ludwig_Raders_-_Jugend.jpg/130px-Ludwig_Raders_-_Jugend.jpg)

![Vol. XX, No. 1 (1915) by Paul Rieth [de]. A German soldier](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Paul_Rieth_-_Jugend_1915_-_vol_1.jpg/135px-Paul_Rieth_-_Jugend_1915_-_vol_1.jpg)

![Vol. XXXV, No. 32 (1930) by Konrad Westermayr [de]. A German soldier](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Titel_Jugend_1930_32.JPG/131px-Titel_Jugend_1930_32.JPG)