The Diary of a Young Girl

1948 first edition | |

| Author | Anne Frank |

|---|---|

| Original title | Het Achterhuis |

| Translator | B. M. Mooyaart-Doubleday |

| Cover artist | Helmut Salden |

| Language | Dutch |

| Subject | |

| Genre | Autobiography Jewish literature |

| Publisher | Contact Publishing |

Publication date | 25 June 1947 |

| Publication place | Netherlands |

Published in English | 1952 |

| Awards | Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century |

| OCLC | 1432483 |

| 949.207 | |

| LC Class | DS135.N6 |

Original text | Het Achterhuis at Dutch Wikisource |

The Diary of a Young Girl, commonly referred to as The Diary of Anne Frank, is a book of the writings from the Dutch-language diary kept by Anne Frank while she was in hiding for two years with her family during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. The family was apprehended in 1944, and Anne Frank died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945. Anne's diaries were retrieved by Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl. Miep gave them to Anne's father, Otto Frank, the family's only survivor, just after the Second World War was over.

The diary has since been published in more than 70 languages. It was first published under the title Het Achterhuis. Dagboekbrieven 14 Juni 1942 – 1 Augustus 1944 (Dutch: [ət ˈɑxtərˌɦœys]; The Annex: Diary Notes 14 June 1942 – 1 August 1944) by Contact Publishing in Amsterdam in 1947. The diary received widespread critical and popular attention on the appearance of its English language translation, Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl by Doubleday & Company (United States) and Vallentine Mitchell (United Kingdom) in 1952. Its popularity inspired the 1955 play The Diary of Anne Frank by the screenwriters Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, which they adapted for the screen for the 1959 movie version. The book is included in several lists of the top books of the 20th century.[1][2][3][4][5]

The copyright of the Dutch version of the diary, published in 1947, expired on 1 January 2016, seventy years after the author's death, as a result of a general rule in copyright law of the European Union. Following this, the original Dutch version was made available online.[6][7]

Background

[edit]During the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, Anne Frank received a blank diary as one of her presents on 12 June 1942, her 13th birthday.[8][9] According to the Anne Frank House, the red, checkered autograph book which Anne used as her diary was actually not a surprise, since she had chosen it the day before with her father when browsing a bookstore near her home.[9] She entered a one-sentence note on her birthday, writing "I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support."[10][11] The main diary was written from 14 June.[12][13]

On 5 July 1942, Anne's then-16-year-old sister, Margot, received an official summons to report to a Nazi work camp in Germany, and on 6 July, Margot and Anne went into hiding with their parents Otto and Edith. They were later joined by Hermann van Pels, Otto's business partner, his wife Auguste and their teenage son Peter.[14] Their hiding place was in the sealed-off upper rooms of the annex at the back of Otto's company building in Amsterdam.[14][15] Otto Frank started his business, named Opekta, in 1933. He was licensed to manufacture and sell pectin, a substance used to make jam. He stopped running his business while in hiding. But once he returned in the summer of 1945, he found his employees running it. The rooms that everyone hid in were concealed behind a movable bookcase in the same building as Opekta. Fritz Pfeffer, the dentist of their helper Miep Gies,[16] joined them four months later. In the published version, names were changed: The van Pelses are known as the Van Daans, and Fritz Pfeffer as Albert Düssel. With the assistance of a group of Otto Frank's trusted colleagues, they remained hidden for two years and one month.[17][18]

On 6 June 1944, the Allied forces commenced the Normandy landings, in France; the group was aware of this development, and hopeful for eventual liberation. On 4 August 1944, six weeks before the Allies breached the Belgian-Dutch border, the group was discovered and deported to Nazi concentration camps. They were long thought to have been betrayed, although there are indications that their discovery may have been accidental, that the police raid had actually targeted "ration fraud".[19] Of the eight people, only Otto Frank survived the war. Anne was 15 years old when she died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, in Nazi Germany. The exact date of her death is unknown, and has long been believed to be in late February or early March, a few weeks before the concentration camp was liberated by British troops on 15 April 1945.[20]

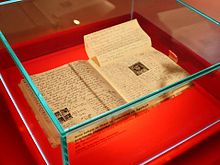

In the manuscript, her original diaries are written over three extant volumes. The first volume (the red-and-white checkered autograph book) covers the period between 14 June and 5 December 1942. Since the second surviving volume (a school exercise book) begins on 22 December 1943, and ends on 17 April 1944, it is assumed that the original volume or volumes between December 1942 and December 1943 were lost, presumably after the arrest, when the hiding place was emptied on Nazi instructions. However, this missing period is covered in the version Anne rewrote for preservation. The third existing volume (which was also a school exercise book) contains entries from 17 April to 1 August 1944, when Anne wrote for the last time three days before her arrest.[21]: 2

The manuscript, written on loose sheets of paper, was found strewn on the floor of the hiding place by Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl after the family's arrest,[22] but before their rooms were ransacked by a special department of the Amsterdam office of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Nazi intelligence agency) for which many Dutch collaborators worked.[23] The papers were given to Otto Frank after the war, when Anne's death was confirmed in July 1945 by sisters Marianne and Rebekka Brilleslijper, who were with Margot and Anne in Bergen-Belsen.[24]

Format

[edit]The diary is not written in the classic forms of "Dear Diary" or as letters to oneself; Anne calls her diary "Kitty", so almost all of the letters are written to Kitty. Anne used the above-mentioned names for her annex-mates in the first volume, from 25 September 1942 until 13 November 1942, when the first notebook ends.[25] It is believed that these names were taken from characters found in a series of popular Dutch books written by Cissy van Marxveldt.[25]

Anne's already budding literary ambitions were galvanized on 29 March 1944 when she heard a London radio broadcast made by the exiled Dutch Minister for Education, Art, and Science, Gerrit Bolkestein,[22] calling for the preservation of "ordinary documents – a diary, letters ... simple everyday material" to create an archive for posterity as testimony to the suffering of civilians during the Nazi occupation. On 20 May 1944, she notes that she started re-drafting her diary with future readers in mind.[26] She expanded entries and standardized them by addressing all of them to Kitty, clarified situations, prepared a list of pseudonyms, and cut scenes she thought would be of little interest or too intimate for general consumption. By the time she started the second existing volume, she was writing only to Kitty.[citation needed]

Dear Kitty

[edit]For many years there was much conjecture about the identity of or inspiration for Kitty. In 1996, the critic Sietse van der Hoek wrote that the name referred to Kitty Egyedi, a prewar friend of Anne's. Van der Hoek may have been informed by the publication A Tribute to Anne Frank (1970), prepared by the Anne Frank Foundation, which assumed a factual basis for the character in its preface by the then-chairman of the Foundation, Henri van Praag, and accentuated this with the inclusion of a group photograph that singles out Anne, Sanne Ledermann, Hanneli Goslar, and Kitty Egyedi. However, Anne does not mention Egyedi in any of her writings (in fact, the only other girl mentioned in her diary from the often reproduced photo, other than Goslar and Ledermann, is Mary Bos, whose drawings Anne dreamed about in 1944) and the only comparable example of Anne's writing un-posted letters to a real friend are two farewell letters to Jacqueline van Maarsen, from September 1942.[27][failed verification]

Theodor Holman wrote in reply to Sietse van der Hoek that the diary entry for 28 September 1942 proved conclusively the character's fictional origin.[citation needed] Jacqueline van Maarsen agreed,[citation needed] but Otto Frank assumed his daughter had her real acquaintance in mind when she wrote to someone of the same name.[citation needed] Kitty Egyedi said in an interview that she was flattered by the possibility it was her, but stated:

Kitty became so idealized and started to lead her own life in the diary that it ceases to matter who is meant by 'Kitty'. The name ... is not meant to be me.[28]

Only when Anne Frank's diaries were transcribed in the 1980s did it emerge that 'Kitty' was not unique; she was one of a group of eight recipients to whom Anne addressed the first few months of her diary entries. In some of the notes, Anne references the other names, suggesting she imagined they all knew each other. With the exception of Kitty, none of the names were of people from Anne's real-life social circle. Three of the names may be imaginary, but five of them correspond to the names of a group of friends from the novels of Cissy van Marxveldt, which Anne was reading at the time. Significantly, the novels are epistolary and include a teenage girl called 'Kitty Francken'. By the end of 1942, Anne was writing solely to her. In 1943, when she started revising and expanding her diary entries, she standardised the form and consolidated all of the recipients to just Kitty.[citation needed]

Synopsis

[edit]Anne expressed the desire in the rewritten introduction of her diary for one person that she can call her truest friend – that is, a person to whom she could confide her deepest thoughts and feelings. She observes that she has had many "friends" and admirers, but (by her own definition) no true, dear friend with whom she could share her innermost thoughts. She originally thought her girl friend Jacque van Maarsen would be this person, but that was only partially successful. In an early diary passage, she remarks that she is not in love with Helmut "Hello" Silberberg, her suitor at that time, but considers that he might become a true friend. In hiding, she invests much time and effort into her budding romance with Peter van Pels, thinking he might evolve into that one, true friend, but that is eventually a disappointment to her in some ways, although she continues to care for him. Ultimately, it was only to Kitty that she entrusted her innermost thoughts.

In her diary, Anne wrote of her very close relationship with her father, lack of daughterly love for her mother (with whom she felt she had nothing in common), and admiration for her sister's intelligence and sweet nature. She did not like the others much initially, particularly Auguste van Pels and Fritz Pfeffer (the latter shared her room). She was at first unimpressed by the quiet Peter; she herself was something of a self-admitted chatterbox (a source of irritation to some of the others). As time went on, however, she and Peter became very close and spent a lot of time together. After a while Anne became disappointed in Peter and on 15 July 1944, she wrote in her diary that Peter could never be a 'kindred spirit'.[29]

Editorial history

[edit]There are two versions of the diary written by Anne Frank. She wrote the first version in a designated diary and two notebooks (version A), but rewrote it (version B) in 1944 after hearing on the radio that war-time diaries were to be collected to document the war period. Version B was written on loose paper, and is not identical to Version A, as parts were added and others omitted.[30]

Publication in Dutch

[edit]"...[Th]ough Anne had made it plain that she wanted to become a famous writer, she had also made it clear that she wanted to keep her diary to herself. But finally [her father] decided that publication was what Anne would have wanted."[31]

The first transcription of Anne's diary was in German, made by Otto Frank for his friends and relatives in Switzerland, who convinced him to send it for publication.[32] The second, a composite of Anne Frank's versions A and B as well as excerpts from her essays, became the first draft submitted for publication, with an epilogue written by a family friend explaining the fate of its author. In the spring of 1946, it came to the attention of Dr. Jan Romein and his wife Annie Romein-Verschoor, two Dutch historians. They were so moved by it that Anne Romein made unsuccessful attempts to find a publisher, which led Romein to write an article for the newspaper Het Parool:[33]

This apparently inconsequential diary by a child, this "de profundis" stammered out in a child's voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence of Nuremberg put together.

— Jan Romein in his article "Children's Voice" on Het Parool, 3 April 1946.[33]

This caught the interest of Contact Publishing in Amsterdam, who approached Otto Frank to submit a Dutch draft of the manuscript for their consideration. They offered to publish, but advised Otto Frank that Anne's candor about her emerging sexuality might offend certain conservative quarters, and suggested cuts. Further entries were also deleted. The diary – which was a combination of version A and version B – was published under the name Het Achterhuis. Dagbrieven van 14 juni 1942 tot 1 augustus 1944 (The Secret Annex. Diary Letters from 14 June 1942 to 1 August 1944) on 25 June 1947.[33] Otto Frank later discussed this moment, "If she had been here, Anne would have been so proud."[33] The book sold well; the 3,000 copies of the first edition were soon sold out, and in 1950 a sixth edition was published.

In 1986, a critical edition appeared, incorporating versions A and B, and based on the findings of the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation into challenges to the diary's authenticity. This was published in three volumes with a total of 714 pages.[34]

Publication in English

[edit]In 1950, the Dutch translator Rosey E. Pool made a first English translation of the diary, which was never published.[35] At the end of 1950, another translator was found to produce an English-language version. Barbara Mooyaart-Doubleday was contracted by Vallentine Mitchell in England, and by the end of the following year, her translation was submitted, now including the deleted passages at Otto Frank's request. As well, Judith Jones, while working for the publisher Doubleday, read and recommended the Diary, pulling it out of the rejection pile.[36] Jones recalled that she came across Frank's work in a slush pile of material that had been rejected by other publishers; she was struck by a photograph of the girl on the cover of an advance copy of the French edition. "I read it all day", she noted. "When my boss returned, I told him, 'We have to publish this book.' He said, 'What? That book by that kid?'" She brought the diary to the attention of Doubleday's New York office. "I made the book quite important because I was so taken with it, and I felt it would have a real market in America. It's one of those seminal books that will never be forgotten", Jones said.[37] The book appeared in the United States and in the United Kingdom in 1952, becoming a best-seller. The introduction to the English publication was written by Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1989, an English edition of this appeared under the title of The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, including Mooyaart-Doubleday's translation and Anne Frank's versions A and B, based on the Dutch critical version of 1986.[38][39] A new translation by Susan Massotty, based on the original texts, was published in 1995.[citation needed]

In 2018, Ari Folman, a son of Holocaust survivors, adapted The Diary of a Young Girl into a graphic novel illustrated by David Polonsky.[40]

Other languages

[edit]The work was translated in 1950 into German and French, before it appeared in 1952 in the US in English.[41] The critical version was also translated into Chinese.[42] By 2014, over 35 million copies had been published, in 65 languages;[43] as of 2019, the website of the Anne Frank House records translations in over 70 languages.[44]

Theatrical and film adaptations

[edit]"The first dramatization, written by the American author Meyer Levin, did not find a producer. Otto Frank, too, had his reservations about Levin's work..."[31]

"Otto was not much happier at first with the second dramatization, written by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett. Only after the couple's reworking of the script had dragged on for two years did Otto give it his approval."[45] A play by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich based on the diary won the Pulitzer Prize for 1955. A subsequent film version earned Shelley Winters an Academy Award for her performance. Winters donated her Oscar to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.[46]

The first major adaptation to quote literal passages from the diary was 2014's Anne, authorised and initiated by the Anne Frank Foundation in Basel. After a two-year continuous run at the purpose-built Theater Amsterdam in the Netherlands, the play had productions in Germany[47] and Israel.

Other adaptations of the diary include a version by Wendy Kesselman from 1997.[48] Alix Sobler's 2014 The Secret Annex imagined the fate of the diary in a world in which Anne Frank survives the Holocaust.[49]

The first German film version of the diary, written by Fred Breinersdorfer, was released by NBCUniversal in 2016. The film is derived from the 2014 Dutch stage production.

In 2021, Folman directed Where Is Anne Frank, an animated magical realism film based on Frank's life, with the animation styled after Polonsky's illustrations for Folman's 2018 graphic novel adaptation of The Diary of a Young Girl. The film centers on Kitty—Frank's imaginary friend to whom she addressed her diary—coming to life in 21st century Netherlands; as Kitty learns of the Frank family's fates in the Holocaust, she helps a number of refugees seek asylum, aware of how similar their plight is to that of the persecuted Jews of WWII.

Censored material

[edit]In 1986 the Dutch Institute for War Documentation published the "Critical Edition" of the diary, containing comparisons from all known versions, both edited and unedited, discussion asserting the diary's authentication, and additional historical information relating to the family and the diary itself.[50] It also included sections of Anne's diaries which had previously been edited out, containing passages on her sexuality, references to touching her friend's breasts, and her thoughts on menstruation.[51][unreliable source?][52][53] An edition was published in 1995 which included Anne's description of her exploration of her own genitalia and her puzzlement regarding sex and childbirth, having previously been edited out by the original publisher.[54][55]

Cornelis Suijk – a former director of the Anne Frank Foundation and president of the U.S. Center for Holocaust Education Foundation – announced in 1999 that he was in possession of five pages that had been removed by Otto Frank from the diary prior to publication; Suijk claimed that Otto Frank gave these pages to him shortly before his death in 1980. The missing diary entries contain critical remarks by Anne Frank about her parents' strained marriage and discuss Frank's lack of affection for her mother.[56] Some controversy ensued when Suijk claimed publishing rights over the five pages; he intended to sell them to raise money for his foundation. The Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, the formal owner of the manuscript, demanded the pages be handed over. In 2000 the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science agreed to donate US$300,000 to Suijk's foundation, and the pages were returned in 2001. Since then, they have been included in new editions of the diary.[57]

In May 2018, Frank van Vree, the director of the Niod Institute along with others, discovered some unseen excerpts from the diary that Anne had previously covered up with a piece of brown paper. The excerpts discuss sexuality, prostitution, and also include jokes Anne herself described as "dirty" that she heard from the other residents of the Secret Annex and elsewhere. Van Vree said "anyone who reads the passages that have now been discovered will be unable to suppress a smile", before adding, "the 'dirty' jokes are classics among growing children. They make it clear that Anne, with all her gifts, was above all an ordinary girl".[58]

Reception

[edit]

In the 1960s, Otto Frank recalled his feelings when reading the diary for the first time, "For me, it was a revelation. There, was revealed a completely different Anne to the child that I had lost. I had no idea of the depths of her thoughts and feelings."[32] Michael Berenbaum, former director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, wrote, "Precocious in style and insight, it traces her emotional growth amid adversity. In it, she wrote, 'In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.'"[32]

In 2009, the notebooks of the diary were submitted by the Netherlands and included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[59]

Criticism of popularity

[edit]Dara Horn, herself a descendant of Holocaust survivors, laments that Anne Frank's account ends with the thought that people are good at heart and the note that Frank died "peacefully" of typhus, shortly before Frank encounters very evil people who took her off at gunpoint to be murdered. Horn feels this allows readers to be absolved of responsibility, and that the popularity of the book derives from its lack of any depiction of the horrors of Nazi death camps. She points to accounts of victims who had more typical experiences, such as Zalmen Gradowski (reportedly one of the inspirations for the film Son of Saul), who was forced to strip his fellow Jews on the way into the gas chambers, with vivid accounts of their last words and actions, and watching the bodies burn during the forced cleanup process. Horn also points out the relative lack of international attention paid to the accounts of survivors of the Holocaust, speculating Frank's diary would not have been popular had she survived, and to ironic dismissal of living Jews, such as an employee of the Anne Frank museum who was told he could not wear a yarmulke.[60][61]

Vandalism

[edit]In February 2014, authorities discovered that 265 copies of the Frank diary and other material related to the Holocaust were vandalized across 31 public libraries in Tokyo.[62][63] The Simon Wiesenthal Center expressed "its shock and deep concern"[64] and, in response, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga called the vandalism "shameful." Israel donated 300 copies of Anne Frank's diary to replace the vandalized copies.[65] An anonymous donor using the pseudonym "Chiune Sugihara" donated two boxes of books pertaining to the Holocaust to the Tokyo Metropolitan Library.[66] Police arrested an unemployed man in March 2014.[67] In June, prosecutors decided not to indict the suspect after he was found to be mentally incompetent.[68] According to librarians in Tokyo, books relating to the Holocaust such as the diary and Man's Search for Meaning attract people with mental disorders and are subject to occasional vandalism.[69][better source needed]

Bans

[edit]In 2009, the group Hezbollah called to ban the book in Lebanese schools, arguing that the text was an apology to Jews, Zionism and Israel.[70]

In 2010, the Culpeper County, Virginia, school system banned the 50th Anniversary "Definitive Edition" of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, due to "complaints about its sexual content and homosexual themes."[71] This version "includes passages previously excluded from the widely read original edition.... Some of the extra passages detail her emerging sexual desires; others include unflattering descriptions of her mother and other people living together."[72] After consideration, it was decided a copy of the newer version would remain in the library and classes would revert to using the older version.

In 2013, a similar controversy arose in a 7th grade setting in Northville, Michigan, focusing on explicit passages about sexuality.[73] The mother behind the formal complaint referred to portions of the book as "pretty pornographic."[74]

In 2010, the American Library Association stated that there have been six challenges to the book in the United States since it started keeping records on bans and challenges in 1990, and that "[m]ost of the concerns were about sexually explicit material".[72]

In 2023, a Texas teacher was fired after assigning an illustrated adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary to her middle school class, in a move that some are calling “a political attack on truth”. The eighth-grade school teacher was fired after officials with Hamshire-Fannett independent school district said the teacher presented the “inappropriate” book to students, reported KFDM.[75]

Authenticity

[edit]As reported in The New York Times in 2015, "When Otto Frank first published his daughter's red-checked diary and notebooks, he wrote a prologue assuring readers that the book mostly contained her words".[76] Although many Holocaust deniers, such as Robert Faurisson, have claimed that Anne Frank's diary was fabricated,[77][78] critical and forensic studies of the text and the original manuscript have supported its authenticity.[79]

The Netherlands Institute for War Documentation commissioned a forensic study of the manuscripts after the death of Otto Frank in 1980. The material composition of the original notebooks and ink, and the handwriting found within them and the loose version were extensively examined. In 1986, the results were published: the handwriting attributed to Anne Frank was positively matched with contemporary samples of Anne Frank's handwriting, and the paper, ink, and glue found in the diaries and loose papers were consistent with materials available in Amsterdam during the period in which the diary was written.[79]

The survey of her manuscripts compared an unabridged transcription of Anne Frank's original notebooks with the entries she expanded and clarified on loose paper in a rewritten form and the final edit as it was prepared for the English translation. The investigation revealed that all of the entries in the published version were accurate transcriptions of manuscript entries in Anne Frank's handwriting, and that they represented approximately a third of the material collected for the initial publication. The magnitude of edits to the text is comparable to other historical diaries such as those of Katherine Mansfield, Anaïs Nin and Leo Tolstoy in that the authors revised their diaries after the initial draft, and the material was posthumously edited into a publishable manuscript by their respective executors, only to be superseded in later decades by unexpurgated editions prepared by scholars.[80]

Nazi sympathizer Ernst Römer accused Otto Frank of editing and fabricating parts of Anne's diary in 1980. Otto filed a lawsuit against him, and the court ruled that the diary was authentic. Römer ordered a second investigation, involving Hamburg's Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt (BKA)). That investigation concluded that parts of the diary were written with ballpoint pen ink, which was not generally available in the 1940s. (The first ball point pens were produced in the 1940s but they did not become generally available until the 1950s.) Reporters were unable to reach out to Otto Frank for questions as he died around the time of the discovery.[81]

However, the ballpoint pen theory has mostly been discredited. There are only three instances where a ballpoint pen was used in the diary: on two scraps of paper that were added into the diary at a later date (the contents of which have never been considered Anne Frank's writing and are usually attributed to being Otto Frank's notes) and in the page numbers (also probably added by Otto Frank while organizing the writings and papers).[82][83]

Copyright and ownership of the originals

[edit]Anne Frank Fonds

[edit]In his will, Otto Frank bequeathed the original manuscripts to the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. The copyright however belonged to the Anne Frank Fonds, a Switzerland-based foundation based in Basel which was the sole inheritor of Frank after his death in 1980. The organization is dedicated to the publication of the diary.[84]

Expiration

[edit]According to the copyright laws in the European Union, as a general rule, rights of authors end seventy years after their death. Hence, the copyright of the diary expired on 1 January 2016. In the Netherlands, for the original publication of 1947 (containing parts of both versions of Anne Frank's writing), as well as a version published in 1986 (containing both versions completely), copyright initially would have expired not 50 years after the death of Anne Frank (1996), but 50 years after publication, as a result of a provision specific for posthumously published works (1997 and 2036, respectively).[citation needed]

When the copyright duration was extended to 70 years in 1995 – implementing the EU Copyright Term Directive – the special rule regarding posthumous works was abolished, but transitional provisions made sure that this could never lead to shortening of the copyright term, thus leading to expiration of the copyright term for the first version on 1 January 2016, but for the new material published in 1986 in 2036.[7][30]

The original Dutch version was made available online by University of Nantes lecturer Olivier Ertzscheid and former member of the French Parliament Isabelle Attard.[6][85]

Authorship

[edit]In 2015, the Anne Frank Fonds made an announcement, as reported in The New York Times, that the 1947 edition of the diary was co-authored by Otto Frank. According to Yves Kugelmann, a member of the board of the foundation, their expert advice was that Otto had created a new work by editing, merging, and trimming entries from the diary and notebooks and reshaping them into a "kind of collage", which had created a new copyright. Agnès Tricoire, a lawyer specializing in intellectual property rights, responded by warning the foundation to "think very carefully about the consequences". She added "If you follow their arguments, it means that they have lied for years about the fact that it was only written by Anne Frank."[76]

The foundation also relies on the fact that another editor, Mirjam Pressler, had revised the text and added 25 percent more material drawn from the diary for a "definitive edition" in 1991, and Pressler was still alive in 2015, thus creating another long-lasting new copyright.[76] The move was seen as an attempt to extend the copyright term. Attard had criticised this action only as a "question of money",[85] and Ertzscheid concurred, stating, "It [the diary] belongs to everyone. And it is up to each to measure its importance."[86]

See also

[edit]- List of posthumous publications of Holocaust victims

- List of best-selling books

- List of people associated with Anne Frank

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

References

[edit]- ^ "Top 10) definitive book(s) of the 20th century". The Guardian.

- ^ "50 Best Books defining the 20th century". PanMacMillan.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "List of the 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of the Century, #20". National Review. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Books of the Century: War, Holocaust, Totalitarianism. New York Public Library. 1996. ISBN 978-0-19-511790-5.

- ^ "Top 100 Books of the 20th century, while there are several editions of the book. The publishers made a children's edition and a thicker adult edition. There are hardcovers and paperbacks, #26". Waterstone's. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ a b Attard, Isabelle (1 January 2016). "Vive Anne Frank, vive le Domaine Public" [Long live Anne Frank, long live the Public Domain] (in French). Retrieved 8 July 2019.

The files are available in TXT and ePub format.

- ^ a b Avenant, Michael (5 January 2016). "Anne Frank's diary published online amid dispute". It Web. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Anne Frank Diary Anniversary Marks the Day Holocaust Victim Received Autograph Book as a Birthday Present (PHOTO)". The Huffington Post. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Anne Frank's birthday on theme of diary's 70th anniversary". Anne Frank House. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ Verhoeven, Rian (1995). Anne Frank: Beyond the Diary – A Photographic Remembrance. New York: Puffin. p. 4. ISBN 0-14-036926-0.

- ^ Hawker, Louise (2011). Genocide in Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7377-6115-3.

- ^ Christianson, Scott (12 November 2015). "How Anne Frank's Diary Changed the World". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Anne Frank's 'The Diary of a Young Girl': When a 15-year-old showed us the Holocaust experience". India Today. 11 August 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Anne Frank Biography (1929–1945)". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "The hiding place – A bookcase hides the entrance". Anne Frank House. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Fritz Pfeffer". Anne Frank House. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Anne Frank captured". history.com. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Chiu, Allyson (16 May 2018). "Anne Frank's hidden diary pages: Risque jokes and sex education". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "Anne Frank may have been discovered by chance, new study says". BBC News. 17 December 2016.

- ^ Park, Madison (1 April 2015). "Researchers say Anne Frank perished earlier than thought". CNN.

- ^ "Ten questions on the authenticity of the diary of Anne Frank" (PDF). Anne Frank Stichting. 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ a b Frank, Anne (1997). The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definite Edition. Bantam Books. p. vii. ISBN 0553577123.

- ^ Verhoeven, Rian (2019). Anne Frank was niet alleen. Het Merwedeplein 1933–1945. Amsterdam: Prometheus. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-9044630411.

- ^ "'Ruski', Otto Frank wrote upon the liberation of camp Auschwitz". Anne Frank House. 21 January 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Jennifer. "5 Things You Don't Know about Anne Frank and Her Diary". About.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "The Different Versions of Anne's Diary". Anne Frank House. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "Facts about The Diary of Anne Frank". Christian Memorials. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Quotes by Kathe Egyedi from Quotes.net". Quotes.net. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Peter van Pels". Anne Frank House. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b Court of Amsterdam, 23 December 2015, ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2015:9312

- ^ a b Anne Frank: The Biography, Melissa Muller, updated and expanded edition 2013, Metropolitan Books, p. 340, ISBN 978-0-8050-8731-4.

- ^ a b c Noonan, John (25 June 2011). "On This Day: Anne Frank's Diary Published". Finding Dulcinea. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Anne Frank's diary is published". Anne Frank House. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Hyman Aaron Enzer, Sandra Solotaroff-Enzer, Anne Frank: Reflections on Her Life and Legacy (2000), p. 136

- ^ Carol Ann Lee, The Hidden Life of Otto Frank (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 191-192

- ^ Jones, Judith (2008). The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. Chapter: Paris for Keeps. ISBN 978-0307498250. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Tabachnick, Toby (2009). "The editor who didn't pass on Anne Frank; Jones recalls famous diary". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016 – via Firefox.

- ^ Betty Merti, The World of Anne Frank: A Complete Resource Guide (1998), p. 40

- ^ Frank, Anne, and Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation (2003) [1989]. The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385508476.

- ^ Frank, Anne; Folman, Ari (2 October 2018). "Anne Frank's Diary: The Graphic Adaptation". Pantheon.

- ^ "Origin". Anne Frank Fonds. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ See Frank 1947

- ^ Berger, Joseph (4 November 2014). "Recalling Anne Frank, as Icon and Human Being". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "The diary". Anne Frank House. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Anne Frank: The Biography, Melissa Muller, updated and expanded edition 2013, Metropolitan Books, pp. 341, ISBN 978-0-8050-8731-4.

- ^ "Shelley Winters wins the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Mrs van Pels in "The Diary of Anne Frank"". Anne Frank House. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Anne celebrated its premiere in Hamburg". Anne Frank Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ "The Diary of Anne Frank (Adaptation by Wendy Kesselman)".

- ^ "The Secret Annex brings a complex Anne Frank to life at RMTC | CBC News".

- ^ Frank 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Blakemore, Erin (23 July 2019). "Hidden Pages in Anne Frank's Diary Deciphered After 75 Years". History.com.

- ^ Waaldijk, Berteke (July 1993). "Reading Anne Frank as a woman". Women's Studies International Forum. 16 (4): 327–335. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(93)90022-2.

- ^ "Censoring Anne Frank: how her famous diary has been edited through history". HistoryExtra.

- ^ Boretz, Carrie (10 March 1995). "Anne Frank's Diary, Unabridged". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ O'Toole, Emer (2 May 2013). "Anne Frank's diary isn't pornographic – it just reveals an uncomfortable truth". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (10 September 1998). "Five precious pages renew wrangling over Anne Frank". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Müller, Melissa (2013) [1998]. Anne Frank: The Biography (in German). New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 342–344. ISBN 978-0805087314.

- ^ "Anne Frank's 'dirty jokes' uncovered". BBC News. 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Diaries of Anne Frank". Memory of the World. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ How We've Used Anne Frank – KERA-FM Think! interview

- ^ "Becoming Anne Frank". Smithsonian. November 2018.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (21 February 2014). "'Diary of Anne Frank' Vandalized at Japanese Libraries". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Mullen, Jethro (21 February 2014). "Pages torn from scores of copies of Anne Frank's diary in Tokyo libraries". CNN. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Wiesenthal Center Expresses Shock and Deep Concern Over Mass Desecrations of The Diary of Anne Frank in Japanese Libraries". 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Brown, Sophie (28 February 2014). "Israel donates hundreds of Anne Frank books to Tokyo libraries after vandalism". CNN. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Israel donates Anne Frank books to Japan after vandalism". Associated Press/Haaretz. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Japan arrest over Anne Frank book vandalism". BBC. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "No charges for Japanese in Anne Frank diary vandalism case: Report". The Straits Times/AFP. 19 June 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ ""中二病"の犯行ではない!? 被害は30年以上前から…図書館関係者が口に出せない『アンネの日記』破損事件の背景" (in Japanese). 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Anne Frank diary offends Lebanon's Hezbollah". Ynetnews. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "The Neverending Campaign to Ban 'Slaughterhouse Five'". The Atlantic. 12 August 2011.

- ^ a b Michael Alison Chandler (29 January 2010). "School system in Va. won't teach version of Anne Frank book". The Washington Post.

- ^ Maurielle Lue (24 April 2013). "Northville mother files complaint about passages in the unedited version of The Diary of Anne Frank". WJBK – Fox 2 News. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

The following is the passage from The Definitive Edition of the Diary of a Young Girl that has a mother in Northville filing a formal complaint. 'Until I was eleven or twelve, I didn't realize there was a second set of labia on the inside, since you couldn't see them. What's even funnier is that I thought urine came out of the clitoris…. When you're standing up, all you see from the front is hair. Between your legs there are two soft, cushiony things, also covered with hair, which press together when you're standing, so you can't see what's inside. They separate when you sit down and they're very red and quite fleshy on the inside. In the upper part, between the outer labia, there's a fold of skin that, on second thought, looks like a kind of blister. That's the clitoris.'

- ^ Flood, Alison (7 May 2013). "Anne Frank's Diary in US schools censorship battle". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Oladipo, Gloria (20 September 2023). "Texas teacher fired for showing Anne Frank graphic novel to eighth-graders". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c Doreen Carvajal, Anne Frank's Diary Gains 'Co-Author' in Copyright Move dated 13 November 2015

- ^ "The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial?", JPR Report, 3, 2000, archived from the original on 18 July 2011; Prose, Francine (2009). Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife. New York: Harper. pp. 239–249. ISBN 978-0061430794.

- ^ Faurisson, Robert (1982), "Is The Diary of Anne Frank genuine?", The Journal of Historical Review, 3 (2): 147

- ^ a b Mitgang, Herbert (8 June 1989), "An Authenticated Edition of Anne Frank's Diary", The New York Times

- ^ Lee, Hermione (2 December 2006), "The Journal of Katherine Mansfield", The Guardian

- ^ "Blaue paste (Blue paste)". Der Spiegel. 5 October 1980. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "ANNE FRANK'S DIARY: WRITTEN IN BALLPOINT PEN?". Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (8 June 1989). "An Authenticated Edition of Anne Frank's Diary". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Work". Anne Frank Fonds. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Anne Frank's diary published online despite rights dispute, as 70 years since her death passes". ABC. 2 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Sinha, Sanskrity (2 January 2016). "Anne Frank: Diary of a Young Girl published online amid copyright dispute". International Business Times. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Frank, Anne (1995) [1947], Frank, Otto H.; Pressler, Mirjam (eds.), Het Achterhuis [The Diary of a Young Girl – The Definitive Edition] (in Dutch), Massotty, Susan (translation), Doubleday, ISBN 0385473788; This edition, a new translation, includes material excluded from the earlier edition.

- Frank, Anne (2003) [1989]. Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation (ed.). The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385508476.

Further reading

[edit]Copyright and ownership dispute

[edit]- Lebovic, Matt (18 December 2014). "A most unseemly battle over the legacy of Anne Frank (In feud with Amsterdam museum, copyright holders are using final year before diaries enter the public domain to push a play, a TV docudrama, films, apps and an archive)". Jewish Times.

- Mullin, Joe (16 November 2015). "Anne Frank foundation moves to keep famous diary copyrighted for 35 more years". Ars Technica. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

Editions of the diary

[edit]- Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank, Eleanor Roosevelt (Introduction) and B.M. Mooyaart (translation). Bantam, 1993. ISBN 0553296981 (paperback). (Original 1952 translation)

- The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, Harry Paape, Gerrold Van der Stroom, and David Barnouw (Introduction); Arnold J. Pomerans, B. M. Mooyaart-Doubleday (translators); David Barnouw and Gerrold Van der Stroom (Editors). Prepared by the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation. Doubleday, 1989.

- The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition, Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler (Editors); Susan Massotty (Translator). Doubleday, 1991.

- Anne Frank Fonds: Anne Frank: The Collected Works. All official versions together with further images and documents. With background essays by Gerhard Hirschfeld and Francine Prose. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019

Adaptations

[edit]- Jacobson, Sid; Ernie Colón (2010). A Graphic Biography: The Anne Frank Diary. The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Luitingh.

- The Beauty That Still Remains, choral work by Marcus Paus based on Frank's diary and written for the official 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Norway

- Folman, Ari; Polonsky, David (2 October 2018). Anne Frank's Diary: The Graphic Adaptation. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-1101871799.

Other writing by Anne Frank

[edit]- Frank, Anne. Tales from the Secret Annex: Stories, Essay, Fables and Reminiscences Written in Hiding, Anne Frank (1956 and revised 2003)

Publication history

[edit]- Lisa Kuitert: De uitgave van Het Achterhuis van Anne Frank, in: De Boekenwereld, Vol. 25 hdy dok

Translation information

[edit]- Schroth, Simone (Summer 2014). "Translating Anne Frank's "Het Achterhuis"". Translation and Literature. 23 (2 Holocaust Testimony and Translation). Edinburgh University Press: 235–243. doi:10.3366/tal.2014.0153. JSTOR 24585357.

Biography

[edit]- Anne Frank Remembered: The Story of the Woman Who Helped to Hide the Frank Family, Miep Gies and Alison Leslie Gold. Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0671662341 (paperback).

- The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank, Willy Lindwer. Anchor, 1992. ISBN 0385423608 (paperback).

- filmed as Laatste Zeven Maanden van Anne Frank (English title: The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank) in 1988, directed by Willy Lindwer.

- Anne Frank: Beyond the Diary – A Photographic Remembrance, Rian Verhoeven, Ruud Van der Rol, Anna Quindlen (Introduction), Tony Langham (Translator) and Plym Peters (Translator). Puffin, 1995. ISBN 0140369260 (paperback).

- Memories of Anne Frank: Reflections of a Childhood Friend, Hannah Goslar and Alison Gold. Scholastic Paperbacks, 1999. ISBN 0590907239 (paperback).

- "Memories Mean More to Us than Anything Else: Remembering Anne Frank's Diary in the 21st century" by Pinaki Roy, The Atlantic Literary Review Quarterly (ISSN 0972-3269; ISBN 978-8126910571), New Delhi,[1] 9(3), July–September 2008: 11–25.

- An Obsession with Anne Frank: Meyer Levin and the Diary, Lawrence Graver. University of California Press, 1995. [ISBN missing]

- Roses from the Earth: The Biography of Anne Frank, Carol Ann Lee. Penguin, 1999. [ISBN missing]

- La porta di Anne, Guia Risari. Mondadori, 2016. ISBN 978-8804658887.

- The Hidden Life of Otto Frank, Carol Ann Lee. William Morrow, 2002.

- Anne Frank: The Biography, Melissa Müller. Bloomsbury, 1999. Updated and expanded edition in 2013, published by Metropolitan Books, 459 pages. ISBN 978-0805087314.

- My Name Is Anne, She Said, Anne Frank, Jacqueline van Maarsen. Arcadia Books, 2007.

- The Last Secret of the Secret Annex: The Untold Story of Anne Frank, Her Silent Protector, and a Family Betrayal, Joop van Wijk-Voskuijl and Jeroen De Bruyn. Simon & Schuster, 2023. ISBN 978-1982198213.

External links

[edit]- The history of the diary of Anne Frank

- About the Diary of Anne Frank

- Anne's manuscripts

- Online exhibition of Anne Frank's manuscripts

- Anne Frank Quotes

- ^ "The Atlantic Literary Review". Franklin. Philadelphia: Library of the University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Anne Frank

- Diaries

- 1947 non-fiction books

- Books adapted into plays

- Non-fiction books adapted into films

- Books published posthumously

- Books about Anne Frank

- Obscenity controversies in literature

- Doubleday (publisher) books

- Dutch-language books

- Dutch non-fiction literature

- Forgery controversies

- Jewish literature

- Memory of the World Register

- Public domain books

- Holocaust diaries

- Censored books

- Books by Anne Frank

- Collaborative non-fiction books