Deep Impact (film)

| Deep Impact | |

|---|---|

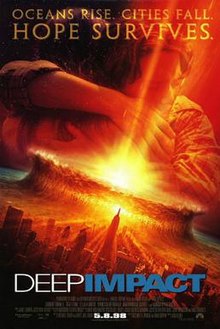

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mimi Leder |

| Written by | Bruce Joel Rubin Michael Tolkin |

| Produced by | David Brown Richard D. Zanuck |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dietrich Lohmann |

| Edited by | Paul Cichocki David Rosenbloom |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | Paramount Pictures DreamWorks Pictures Amblin Entertainment The Manhattan Project Zanuck/Brown Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (United States and Canada) DreamWorks Pictures (through United International Pictures, international) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80 million[1] |

| Box office | $349.5 million[2] |

Deep Impact is a 1998 American science fiction disaster film[3] directed by Mimi Leder, written by Bruce Joel Rubin and Michael Tolkin, and starring Robert Duvall, Téa Leoni, Elijah Wood, Vanessa Redgrave, Maximilian Schell, and Morgan Freeman. Steven Spielberg served as an executive producer of this film. It was released by Paramount Pictures in North America and by DreamWorks Pictures internationally on May 8, 1998. The film depicts humanity's attempts to prepare for and destroy a 7-mile (11 km) wide comet set to collide with Earth and cause mass extinction.

Deep Impact was released in the same summer as the similarly themed Armageddon, which fared better at the box office, while astronomers described Deep Impact as being more accurate.[4][5] Deep Impact was slightly better received critically than Armageddon, although both ultimately received mixed reviews. Deep Impact grossed over $349.5 million worldwide on an $80 million production budget, becoming the sixth highest-grossing film of 1998.

It was the final film by cinematographer Dietrich Lohmann, who died before the film's release.[6]

Plot

[edit]In May 1998, at a star party in Virginia, teenage amateur astronomer Leo Biederman observes an unidentified object in the night sky. He sends a picture to astronomer Dr. Marcus Wolf, who realizes it is a comet on collision course with Earth. Wolf dies in a car crash while racing to raise the alarm.

A year later, MSNBC journalist Jenny Lerner investigates Secretary of the Treasury Alan Rittenhouse over his connection with "Ellie", whom she assumes to be a mistress; she is confused when she finds him and his family loading a boat with large amounts of food and other survival gear. She is apprehended by the FBI and taken to meet President Tom Beck, who persuades her not to share the story in return for a prominent role in the press conference he will arrange. She subsequently discovers that "Ellie" is actually an acronym—E.L.E.—which stands for "extinction-level event". Two days later, Beck announces that the comet Wolf–Biederman is on course to impact the Earth in roughly one year and could cause humanity's extinction. He reveals that the United States and Russia have been constructing the Messiah in orbit, a spacecraft to transport a team to alter the comet's path with nuclear bombs.

The Messiah launches a short time later with a crew of five American astronauts and one Russian cosmonaut. They land on the comet's outer-most layer and drill the nuclear bombs deep beneath its surface, but the comet shifts into the sunlight. Consequently, one astronaut is blinded and another propelled into space by an explosive release of gas. The remaining crew escape the comet and detonate the bombs. However, rather than deflect the comet, the bombs split it in two. Beck announces the mission's failure in a television address, and that both pieces—the larger now named Wolf and the smaller named Biederman—are still headed for Earth. Wolf is on a collision course with western Canada, and its impact is expected to fill the atmosphere with dust, blocking all sunlight for two years and creating an impact winter that will kill all life on the planet's surface.

Martial law is imposed and a lottery selects 800,000 Americans to join 200,000 pre-selected individuals in underground shelters in Missouri's limestone bluffs. Lerner is pre-selected, as are the Biederman family as gratitude for discovering the comet, though Leo's girlfriend Sarah and her family are not selected. Lerner's mother, upon learning most senior citizens are ineligible for the lottery, commits ritual suicide. Leo marries Sarah in a vain attempt to save her family; while this saves Sarah, her family are still not selected, and she refuses to go without them. A last-ditch effort to deflect the comets with ICBMs fails. Upon arrival at the shelter, Leo eschews his safety and leaves to find Sarah. He reaches her on the freeway and takes her and her baby brother to higher ground while her parents remain. Lerner gives up her seat on an evacuation helicopter to a colleague and her young daughter, instead traveling to a beach where she reconciles with her estranged father.

The Biederman fragment hits the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, creating a megatsunami that destroys much of the East Coast of the United States, reaching the Ohio River Valley, and also hitting Europe and Africa. Millions are killed, including Sarah’s parents, Lerner, and her father. Leo, Sarah, and her baby brother survive after making it to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The crew of Messiah, now dangerously low on both life-support and remaining propellant fuel, decide to sacrifice themselves to destroy the larger Wolf fragment by flying deep inside it and detonating their remaining nuclear bombs. They say goodbye to their loved ones by video call and execute their plan. Wolf is blown into smaller pieces which burn up harmlessly in the Earth's atmosphere, averting further catastrophe.

After the waters recede, President Beck speaks to a large crowd at an under-construction replacement United States Capitol.

Cast

[edit]Crew of the Messiah Spacecraft

- Robert Duvall as Captain Spurgeon "Fish" Tanner, a widowed veteran astronaut and rendezvous pilot

- Ron Eldard as Commander Oren Monash, Mission Commander

- Jon Favreau as Dr. Gus Partenza, medical officer

- Aleksandr Baluev as Colonel Mikhail "Mick" Tulchinsky, a Russian cosmonaut and nuclear specialist

- Mary McCormack as Andrea "Andy" Baker, pilot

- Blair Underwood as Mark Simon, navigator

- Kimberly Huie as Wendy Mogel, Mark Simon's fiancée

- Kurtwood Smith as Otis "Mitch" Hefter, the mission flight director

Government Officials

- Morgan Freeman as Tom Beck, the President of the United States

- James Cromwell as Alan Rittenhouse, the Secretary of the Treasury who resigns in light of the Wolf–Biederman comet threat

- O'Neal Compton as Morten Entriken, advisor to the President

- Francis X. McCarthy as General Scott

Lerner Family and MSNBC Associates

- Téa Leoni as Jenny Lerner, an MSNBC journalist

- Vanessa Redgrave as Robin Lerner, Jenny's mother

- Maximilian Schell as Jason Lerner, Jenny's estranged father

- Rya Kihlstedt as Chloe Lerner, Jason's 2nd wife

- Laura Innes as Beth Stanley, MSNBC's White House correspondent, and one of Jenny's co-workers

- Mark Moses as Tim Urbanski, an MSNBC anchor, and one of Jenny's co-workers

- Dougray Scott as Eric Vennekor, one of Jenny's co-workers

- Bruce Weitz as Stuart Caley, Jenny's boss at MSNBC

Biederman Family and Associates

- Elijah Wood as Leo Biederman, a teenage astronomer who discovers the Wolf–Biederman comet

- Charles Martin Smith as astronomer Marcus Wolf

- Richard Schiff as Don Biederman, Leo's father

- Betsy Brantley as Ellen Biederman, Leo's mother

- Leelee Sobieski as Sarah Hotchner, Leo's girlfriend

- Denise Crosby as Vicky Hotchner, Sarah's mother

- Gary Werntz as Chuck Hotchner, Sarah's father

- Mike O'Malley as Mike Perry, Leo's teacher

Production

[edit]The origins of Deep Impact started in the late 1970s when producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown approached Paramount Pictures proposing a remake of the 1951 film When Worlds Collide.[7] Although several screenplay drafts were completed, the producers were not completely happy with any of them and the project remained in "development hell" for many years. In the mid-1990s, they approached director Steven Spielberg, with whom they had made the 1975 blockbuster Jaws, to discuss their long-planned project.[7] However, Spielberg had already bought the film rights to the 1993 novel The Hammer of God by Arthur C. Clarke, which dealt with a similar theme of an asteroid on a collision course for Earth and humanity's attempts to prevent its own extinction. Spielberg planned to produce and direct The Hammer of God himself for his then-fledgling DreamWorks studio, but opted to merge the two projects with Zanuck and Brown, and they commissioned a screenplay for what would become Deep Impact.[7]

In 1995, the forthcoming film was announced in industry publications as "Screenplay by Bruce Joel Rubin, based on the film When Worlds Collide and The Hammer of God by Arthur C Clarke"[8] though ultimately, following a subsequent redraft by Michael Tolkin, neither source work would be credited in the final film. Spielberg still planned to direct Deep Impact himself, but commitments to his 1997 film Amistad prevented him from doing so in time, particularly as Touchstone Pictures had just announced their own similarly-themed film Armageddon, also to be released in summer 1998.[7] Not wanting to wait, the producers opted to hire Mimi Leder to direct Deep Impact, with Spielberg acting as executive producer.[7] Leder was unaware of the other film being made. “I couldn’t believe it. And the press was trying to pit us against each other. That didn’t feel good. Both films have great value and, fortunately, they both succeeded tremendously." Clarke's novel was used as part of the film's publicity campaign both before and after the film's release[9][10][11][12] and he was disgruntled about not being credited on the film.[13][14]

Jenny Lerner, the character played by Téa Leoni, was originally intended to work for CNN. CNN rejected this because it would be "inappropriate". MSNBC agreed to be featured in the movie instead, seeing it as a way to gain exposure for the then newly created network.[15]

Director Mimi Leder later explained that she would have liked to travel to other countries to incorporate additional perspectives, but due to a strict filming schedule and a comparatively low budget, the idea was scratched.[16] Visual effects supervisor Scott Farrar felt that coverage of worldwide events would have distracted and detracted from the main characters' stories.[16]

A number of scientists worked as science consultants for the film including astronomers Gene Shoemaker, Carolyn Shoemaker, Josh Colwell and Chris Luchini, former astronaut David Walker, and the former director of the NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Gerry Griffin.[17]

Soundtrack

[edit]| Deep Impact – Music from the Motion Picture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | May 5, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1997–1998 | |||

| Genre | Film score | |||

| Length | 77:12 | |||

| Label | Sony Classical | |||

| James Horner chronology | ||||

| ||||

The music for the film was composed and conducted by James Horner.

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]Deep Impact was released by Paramount Pictures in the United States and DreamWorks Pictures internationally on May 8, 1998.

Home media

[edit]Deep Impact was released on VHS on October 20, 1998, LaserDisc on November 3 and DVD on December 15.[18]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Deep Impact debuted at the North American box office with $41 million in ticket sales. It managed to cross over Twister, scoring the tenth-highest opening weekend of all time.[19] For a decade, the film held the record for having the biggest opening weekend for a female-directed film until it was taken by Twilight in 2008.[20] The film grossed $140 million in North America and an additional $209 million worldwide for a total gross of $349 million. Despite competition in the summer of 1998 from the similar Armageddon, both films were widely successful, with Deep Impact being the higher opener of the two, while Armageddon was the most profitable overall.[2]

Critical reception

[edit]Deep Impact had a mixed critical reception. Based on 98 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, 45% of critics enjoyed the film, with an average rating of 5.8/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "A tidal wave of melodrama sinks Deep Impact's chance at being the memorable disaster flick it aspires to be."[21] Metacritic gave a score of 40 out of 100 based on 20 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[22] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[23]

Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times said that the film "has a more brooding, thoughtful tone than this genre usually calls for",[24] while Rita Kempley and Michael O'Sullivan of The Washington Post criticized what they saw as unemotional performances and a lack of tension.[25][26]

Accolades

[edit]At the 1998 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, the film was nominated for Worst Supporting Actress for Leoni (lost to Lacey Chabert for Lost in Space) and Worst Screenplay For A Film Grossing More Than $100 Million (Using Hollywood Math) (lost to Godzilla).[27] The film was also nominated for Best Science Fiction Film at the Saturn Awards but lost to both Dark City and another asteroid film, Armageddon.[28]

See also

[edit]- Greenland (film)

- Impact event

- Impact crater

- Asteroid deflection strategies

- List of disaster films

- Hollywood Science

References

[edit]- ^ "Deep Impact". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Archived from the original on February 14, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Deep Impact". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Stweart, Bhob. "Deep Impact". Allmovie. RhythmOne. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Disaster Movies". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ^ Plait, Phil (February 17, 2000). "Hollywood Does the Universe Wrong". Space.com. TechMedia Network. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (November 20, 1997). "Dietrich Lohmann; Widely Praised Cinematographer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Shapiro, Mark (May 1998). "When Worlds Collide Anew (On Location for Deep Impact...)". Starlog. New York, US: Starlog Group, Inc. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ "Deep Impact". The Film Journal. 98 (1–6). Pubsun Corporation. 1995. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "Arthur C's Pool Of Knowledge". Saga Magazine. Saga plc. 1997. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "Deep Impact - Full Cast and Credits - 1998". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ TV Guide Film and Video Companion 2005. Barnes & Noble. 2004. p. 232. ISBN 978-0760761045.

- ^ Grant, Edmund (1999). The Motion Picture Guide 1999 Annual. Cinebooks. p. 94. ISBN 978-0933997431.

- ^ Coker, John L. III (September 1999). "A Visit with Arthur C.Clarke". Locus. Locus Publications. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ United States House Science Subcommittee on Space (1998). The threat and the opportunity of asteroids and other near-earth objects (Report). Vol. 4. United States Government Publishing Office. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "MSNBC gets role in Deep Impact after CNN declines". HighBeam Research. Cengage. Associated Press. April 30, 1998. Retrieved June 25, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ a b Leder, Mimi and Farrar, Scott. Audio commentary. Deep Impact DVD. Universal Studios, 2004.

- ^ Kirby, David A. (2011). Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262014786. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ "'Mercury Rising' and 'Deep Rising' due on video". The Kansas City Star. September 11, 1998. p. 106. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved April 8, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Deep Impact' Shoots to Top on Its First Weekend". Los Angeles Times. May 12, 1998. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Larry Carroll (November 24, 2008). "'Twilight' Tuesday Finale: Director Catherine Hardwicke Raves About Film's Success — 'Unbelievable!'". MTV. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Deep Impact (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "Deep Impact Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 8, 1998). "Movie Review — Deep Impact". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2002. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (March 8, 2000). "'Deep Impact': C'mon Comet!". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Michael (March 8, 2000). "High Profile, Low 'Impact'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ "The Worst of 1998 Winners". Archived from the original on October 13, 1999. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ "Invasion of the Saturn Winners". Wired. June 18, 1999. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1998 films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s disaster films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1998 science fiction films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American disaster films

- American science fiction films

- American survival films

- Comets in film

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- English-language science fiction films

- Fiction about near-Earth asteroids

- Films about astronauts

- Films about families

- Films about fictional presidents of the United States

- Films about impact events

- Films about tsunamis

- Films directed by Mimi Leder

- Films produced by David Brown

- Films produced by Richard D. Zanuck

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in 1998

- Films set in 1999

- Films set in 2000

- Films set in Arizona

- Films set in bunkers

- Films set in Houston

- Films set in Missouri

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in North Carolina

- Films set in the Atlantic Ocean

- Films set in the White House

- Films set in Virginia

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films with screenplays by Bruce Joel Rubin

- Films with screenplays by Michael Tolkin

- Paramount Pictures films

- The Zanuck Company films